Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the primary greenhouse gas (GHG) associated with global warming and climate change. In recent years, researchers have shown that CO2 can be captured from industrial processes or directly from the atmosphere and used as a feedstock to produce renewable fuels. Globally, technological solutions capable of carrying out this process are already being scaled up from research laboratories to industrial-scale production. In Brazil, two projects have the potential to put the country on the map among those with technologies capable of using carbon dioxide as a feedstock to fuel a range of vehicles.

One of the initiatives was conceived at the Chemistry Institute of the University of São Paulo (IQ-USP) within the Research Center for Innovation in Greenhouse Gases (RCGI), a partnership between FAPESP and the British-Dutch energy company Shell. Its objective is to produce a sustainable version of methanol (CH3OH), known as e-methanol, using renewable energy and CO2 captured from ethanol plants. The aim is to use the fuel to power ships, as part of the maritime sector’s efforts toward the energy transition.

Another project, by Sino-Spanish energy company Repsol Sinopec Brasil, is being carried out in partnership with Hytron, a Brazilian startup founded in 2020 by the German group Neuman & Esser, the Center for Technology of the Chemical and Textile Industry of Brazil’s National Service for Industrial Training (SENAI-CETIQT), and USP. The technology being developed, with laboratory support from the RCGI, aims to produce sustainable gasoline and diesel for motor vehicles, aircraft, and ships by recycling CO2.

European EnergyEuropean Energy’s plant, in Denmark, a global pioneer in e-methanol productionEuropean Energy

“We want to offer a national technological alternative to investors interested in producing e-methanol in Brazil,” says chemical engineer Pedro Vidinha, from IQ-USP and cofounder of Carbonic, a startup created in 2022 to make the project commercially viable. The process developed by the team from USP was designed to capture CO2 produced during the fermentation of sugarcane in ethanol plants, but other sources of carbon dioxide can also be used as feedstock. According to Vidinha, sugar-alcohol plants combine three resources in a single location, which together make them competitive for e-methanol production.

One of them is the high availability of CO2 with a high purity level, above 90%, generated during the sugarcane fermentation process. According to the researcher, Brazil produces around 37 billion liters of ethanol per year and the production process emits 28 million tons (t) of CO2. “This amount of gas is enough to serve as feedstock for more than a third of current global methanol production, which is around 98 million tons annually,” compares Vidinha. Weight is the commercial measurement for methanol.

Burning bagasse, the fiber left over after pressing out the sugarcane juice, is a common practice at most ethanol plants and provides the other two resources. The first is electricity, generated from biomass incineration. Since the feedstocks for e-methanol are CO2 and hydrogen (H2), the researchers propose using this electricity to install an H2 production unit. The plant, powered by renewable energy, will produce H2 through water electrolysis, a process that involves breaking down water molecules (H2O) to obtain hydrogen (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 333).

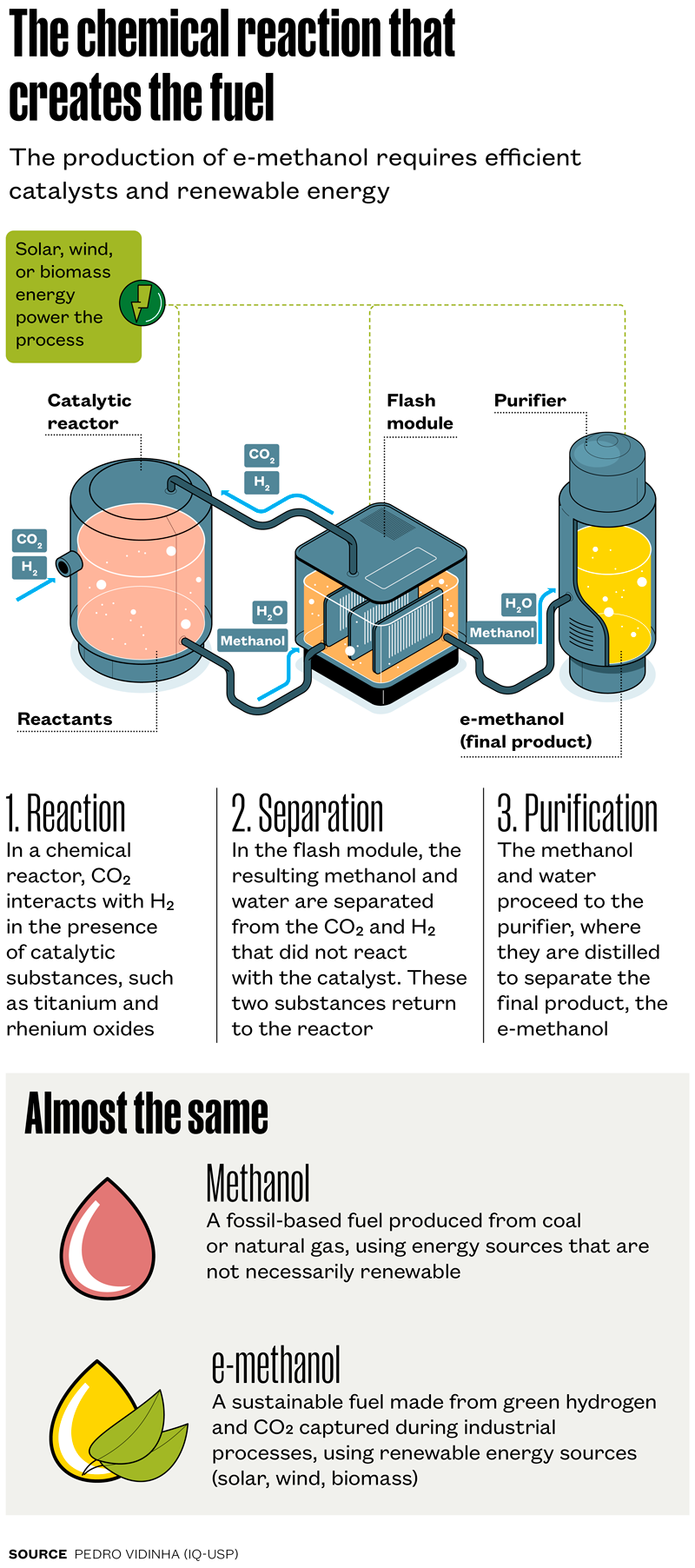

The other resource that results from burning bagasse is steam, which can be used as a process gas and to heat the chemical reactor where the H2 and CO2 molecules are mixed for the production of e-methanol (see infographic below). In this process, the reactor has to work at temperatures between 200 and 250 degrees Celsius (ºC).

Pilot plant

The technological pathway of CO2 capture during sugarcane fermentation is well established and already widely used by the ethanol industry, which sells the captured gas to food and beverage manufacturers. Sustainable hydrogen production technology is also available.

The predominant commercial method for conventional methanol production uses synthesis gas as a feedstock and does not usually use sustainable energy sources. Synthesis gas is obtained through gasification, involving the combustion of fossil-based materials, such as coal or natural gas, mixed with hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Next, the gas undergoes a catalytic reaction, that is, a reaction accelerated by a catalyst—a substance that causes the reaction between chemical reagents without being consumed in the process. The industry-standard catalyst for methanol production is the metallic catalyst made from copper, zinc, and aluminum, known as CZA.

In the IQ-USP project, fossil-origin synthesis gas is replaced by CO2. The process uses a hydrogenation reaction, in which the hydrogen directly converts the CO2 into methanol by means of a catalytic reaction. The main technological challenge for the São Paulo–based team was to create an efficient catalyst to perform this conversion. The solution came through the PhD research of chemist Maitê Lippel Gothe, under the supervision of Vidinha, which resulted in the development of a catalyst based on two components, titanium and rhenium oxides. The patent for the new catalyst has been filed in Brazil and was the focus of an article published in the Journal of CO₂ Utilization in 2020.

In laboratory tests with the reactor at 200 oC, Vidinha reports, the new catalyst is capable of converting around 18% of the CO2 into products such as methanol, methane, and carbon monoxide, presenting a selectivity of 98% for methanol—in other words, methanol corresponds to 98% of the final product. However, the laboratory tests used the catalyst in powdered form, which is unsuitable for industrial-scale production, because it clogs the reactor. At the moment, the catalyst is being structured for use in pellet form, small cylindrical shapes a few millimeters in diameter.

A pilot plant for methanol production is expected to be built by early 2026 at USP’s Cidade Universitária campus, in the city of São Paulo. The experimental unit will test the catalyst in pellet form if its development is successful. The goal is to produce up to 3 liters of methanol per day. “The next step will be to build an industrial demonstration plant at an ethanol plant. There is already interest,” says Vidinha. The researchers estimate that an industrial-scale unit could produce at least 100,000 t of methanol per year. Technical and economic feasibility studies are being carried out. For methanol to be deemed sustainable, that is, classified as e-methanol, the energy used in the production process must come from renewable sources such as wind, solar, or biomass.

MaerskThe container ship Laura Maersk, which runs on the fuelMaersk

Several research groups worldwide are dedicated to manufacturing catalysts suitable for the catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to produce sustainable fuels such as e-methanol. That is one of the main challenges of the process. Chemical engineer Liane Marcia Rossi, from IQ-USP, director of the RCGI, project participant and cofounder of Carbonic, joined an international group that included researchers from University College London, in England, and from the universities of Lorraine, in France, Leiden, in the Netherlands, and Bologna, in Italy, to produce an article presenting a global overview of research in this field. The work, which also discussed the challenges to be overcome, was published in the journal Science in February of this year. The scientists argue that “hydrogenation with CO2 offers a clean fuel solution [e-fuels] for hard-to-electrify sectors, such as aviation and maritime transport.”

Renewable gasoline and diesel

CO2CHEM is the name Repsol Sinopec Brasil has given to its project for producing renewable gasoline and diesel from CO2 and hydrogen. The investment amounts to R$20 million. A pilot unit began operating in March at the Hytron headquarters, in Campinas, and is currently in an assisted operation phase. Production is expected to reach up to 20 liters of renewable fuel per day, using up to 1 t of CO2. According to civil engineer Cassiane Nunes, research portfolio manager at Repsol Sinopec, CO2CHEM uses carbon dioxide and water as raw materials for the production of renewable fuels.

“The CO2 used can come from any source. The H2 is generated by means of water electrolysis, which when combined with carbon dioxide, produces renewable fuels, ensuring a closed cycle of CO2 production and consumption,” explains the engineer. “The system can be powered by renewable energy sources, ensuring the sustainability of the chain.”

The company, according to Nunes, intends to use CO2 captured through Direct Air Capture (DAC) technology at the pilot plant. This technology was implemented in pioneering fashion in Brazil through a project developed in collaboration with the Institute of Petroleum and Natural Resources of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (IPR-PUCRS). DAC technology allows the direct capture of CO2 from the air, removing carbon from the atmosphere (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 340).

Hytron, which started as a spin-off from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in 2003, is responsible for the technological development of the renewable fuel production plant. “The next steps include tests to validate the efficiency of the fuel produced and its performance in different engines, as well as studies on scaling up the production process and its economic feasibility,” states Nunes.

Pioneering Danish technology

Although the technology for e-methanol production, as currently under development at IQ-USP, still requires improvements, the manufacture of this fuel already became a reality in May, when the first factory in the world, located in Kasso, Denmark, began operating with a capacity to produce 42 million tons of e-methanol per year. Powered by renewable energy, the facility uses CO2 captured from biogas plants. The factory is owned by Danish company European Energy and Japanese company Mitsui, and has received €150 million in investments.

The main customer of the renewable fuel manufactured in Kasso is the Danish shipping company Maersk, which operates 12 container ships capable of running on fossil fuel oil or e-methanol. The multinational shipping company has already ordered an additional 20 ships with biofuel-powered engines. According to Maersk, the ships propelled with e-methanol emit 65% less GHGs than those using fossil fuels. The company has announced its intention to increasingly use e-methanol in its ships as it becomes available at ports around the world.

Repsol Sinopec BrasilPilot unit of the CO2CHEM project, in Campinas, for the production of renewable gasoline and dieselRepsol Sinopec Brasil

In Brazil, at least three e-methanol production projects have already been announced, in addition to those cited in this article. In 2024, Petrobras announced a heads of agreement with European Energy for the development of an e-methanol manufacturing plant in Pernambuco. Also last year, Brazilian petrochemical company Braskem signed a partnership with the University of British Columbia, in Canada, to fund the development of technology for producing methanol from CO2. The company’s goal is to manufacture e-methanol to be used as a petrochemical feedstock and fuel.

When contacted for this report, both companies stated that the projects are in the initial phases and that they are unable to provide further details on the matter. Another announced initiative comes from HIF Global, part of the Chilean renewable energy group AME, which has reserved a site at Porto do Açu, in São João da Barra (RJ), to build an e-methanol plant. The company has not provided details about the project.

E-methanol is still not competitive. According to Vidinha, while the fuel presents a cost of around US$1,300 per t, a value that will likely drop significantly when produced on a larger scale, bunker fuel—the fossil fuel oil used to run ships—costs around US$300 per t.

Responsible for 3% of global GHG emissions, the shipping sector aims to reduce its emissions of these pollutants to net-zero by 2050. An agreement established in April this year by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulates decarbonization and sets a timeline of measures for reducing CO2 emissions, which vary by ship size and will be phased in gradually between 2028 and 2050. Noncompliance with the targets will result in fines beginning at US$380 per t of fossil fuel above the permitted amount, rising to over US$1,000 per t by 2050.

The story above was published with the title “When carbon becomes fuel” in issue 354 of August/2025.

Projects

1. Research and Innovation Center for Greenhouse Gases – RCG2I (n° 20/15230-5); Grant Mechanism Engineering Research Centers (CPEs); Agreement BG E&P Brasil (Shell Group); Principal Investigator Julio Romano Meneghini (USP); Investment R$25,376,639.63.

2. Integrated unit for hydrogen production from autothermal reforming of ethanol (nº 14/50183-7); Grant Mechanism Innovative Research in Small Businesses (PIPE); Agreement FINEP RISB/PAPPE Grant Principal Investigator Daniel Lopes (Hytron); Investment R$618,861.42.

3. Development and integration of an integrated ethanol reforming unit for hydrogen production (nº 05/50908-2); Grant Mechanism Innovative Research in Small Businesses (PIPE); Principal Investigator João Carlos Camargo (Hytron); Investment R$614,193.25.

Scientific articles

GOTHE, M. L. et al. Selective CO2hydrogenation into methanol in a supercritical flow process. Journal of CO2 Utilization. Vol. 40, 101195. Sept. 2020.

YE, J. et al. Hydrogenation of CO2for sustainable fuel and chemical production. Science. Vol. 387, no. 6737. Feb. 28, 2025.

Republish