Scientific and higher education institutions in Brazil have started to draft recommendations for the use of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly generative, in teaching, research, and extension. The popularization of software such as ChatGPT, capable of generating text, images, and data, have raised doubts over ethical limits in the use of these technologies, primarily in academic writing. Professors and teachers have sought new ways to assess the work of students in an attempt to circumvent the risks of undue AI use. Generally speaking, the guidance asks that its use be transparent, while warning of the dangers of infringing copyright, practicing plagiarism, generating disinformation, and replicating discriminatory biases that these tools may reproduce.

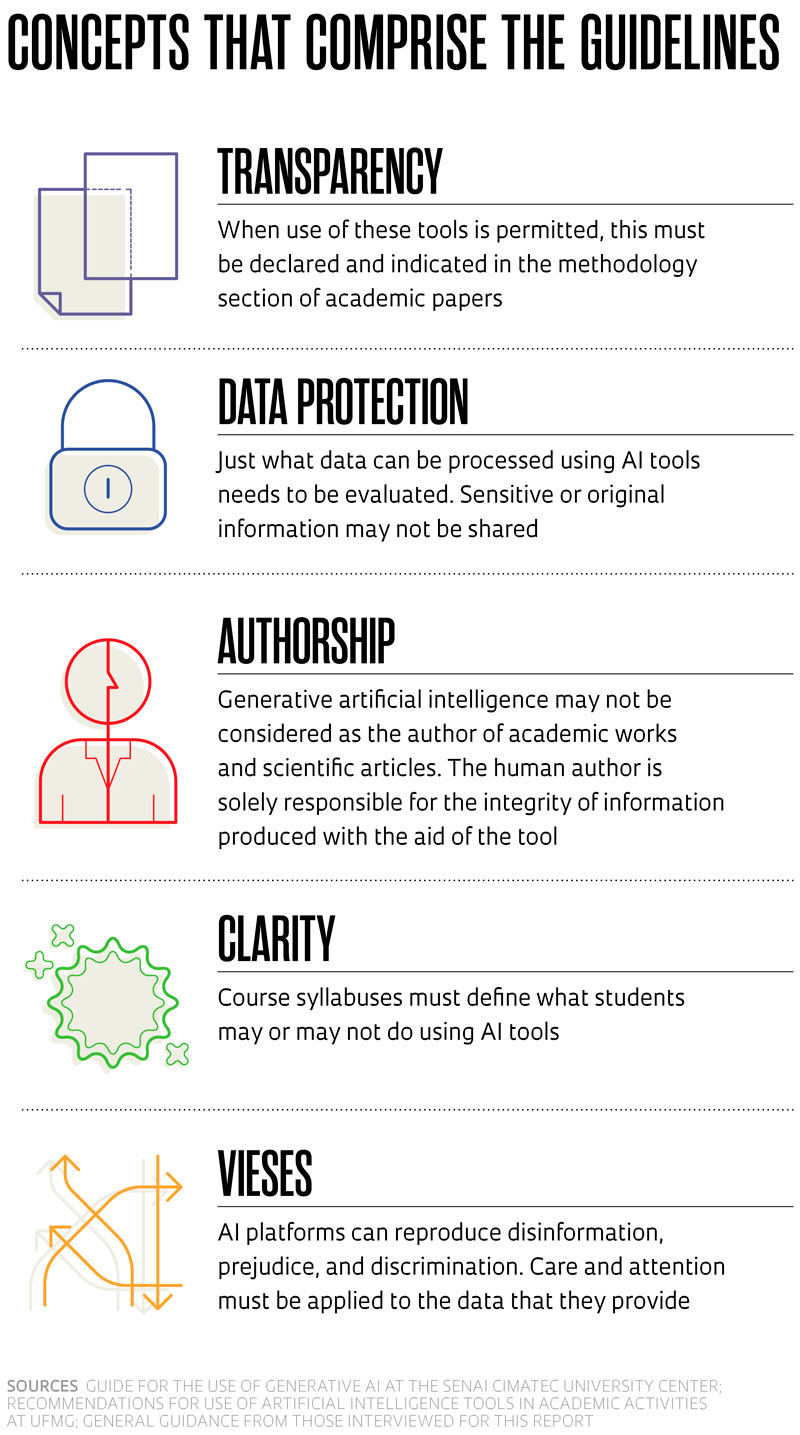

In February, the Brazilian Industrial Education Service (SENAI) CIMATEC University Center, in Bahia State, published a set of guidelines on generative AI for its academic community, based on three principles: transparency; “human-centrality,” i.e. preserving human control of AI-generated information, given that it should be used to the benefit of society; and attention to data privacy, chiefly in activities involving contracts with companies through partnerships for the development and transfer of technologies. Any information shared on AI platforms can be stored by the tool, breaching data confidentiality. “We mustn’t forget that if we learn from these tools, they can also learn from us,” points out civil engineer Tatiana Ferraz, Associate Dean (administrative-financial) of SENAI CIMATEC, and coordinator of the guide. The institution’s disciplinary regulations have been updated to include sanctions for students breaking the rules.

The guide authorizes teaching staff to use plagiary detection software as they deem necessary, although these tools are not 100% accurate for indicating AI-produced content. The tools cannot be cited as coauthors of academic papers, but their application in assisting research processes and fine-tuning academic writing is permitted. To this end, all commands used—the questions and instructions input into the tool, also known as prompts—and the original information generated by AI must be described in the working methodology, and attached as supplementary material.

Other Brazilian institutions are following this lead. “The university should not prohibit, but rather create guidelines for responsible use of these tools, observes computer scientist Virgílio Almeida, coordinator of a commission at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), which proposed recommendations for AI-technology use at the institution, presented to the academic community in May. The suggestions will serve as a basis for creation of an institutional policy with rules and standards, and a permanent governance committee.

They cover areas of education, research, extension, and administration, and include transparency principles for the use of these tools, such as attention to data protection and privacy, disinformation, and discriminatory biases that these technologies may reproduce. “One of the proposals is that the university invests in AI literacy courses for teaching staff, researchers, employees, and students,” explains Almeida. In education, one of the recommendations is that UFMG graduate and postgraduate course syllabuses should inform about what is actually permitted using these technologies. In research, the emphasis is on transparency: details must be given on how AI was used in the scientific process, and what biases may have been brought into it. Careful analysis of AI-generated results is another recommendation for avoiding false data.

The University of São Paulo (USP) published a dossier in Revista USP (USP Magazine) in May on artificial intelligence in scientific research, and has held meetings and debates on the matter. “The overarching suggestion is to study how to incorporate this use into education and research, and examine the ethical limitations and the potential,” observes lawyer Cristina Godoy, of USP’s Ribeirão Preto Law School (FDRP-USP), a member of a group of researchers that drew up proposals for the university, such as the need to create guidelines for graduate and postgraduate students, with warnings about preserving the privacy of sensitive or original research data, such as in theses and dissertations, and the need to look for new ways to assess written work in the classroom setting. The recommendations were made during an event in March 2023, and are being analyzed by a working group.

The use of AI in research is nothing new. Machine learning and natural-language processing tools have long been in use to analyze patterns among large volumes of data, but with the advance of platforms using generative AI, many universities in the United States and Europe have created instructions on the subject, which have served as inspiration for Brazilian institutions. At SENAI CIMATEC, guidelines from the universities of Utah, USA, from July 2023, and Toronto, Canada — still in the preliminary stages — have oriented the working group, along with the quick guide ChatGPT and Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), published in April 2023.

In this context, there are cases of professors who have asked their students to make oral presentations, and work on papers within the classroom, or even hand-write them. Godoy, of USP, who used to request written work on articles studied, came to ask students to present schematics with mental maps showing the connections between the texts studied in class.

In 2024, she developed a research activity within the Artificial Intelligence Center (C4AI) at USP, backed by IBM and FAPESP, with scientific initiation, masters, and PhD students in computing, political science, and law, in which they were required to develop prompts for ChatGPT to analyze feelings — a technique that classifies opinions as positive, negative, or neutral—among users of X (formerly Twitter) on AI. The data will be presented in an article currently being written. One aspect of the work will be to detail the methodology and prompts used. As it was not necessary to create a specific algorithm for this task, the tool accelerated the data analysis process; according to Godoy, if they needed to do everything from scratch, the work would take eight months, but it took ChatGPT two.

“Some Judicial Branch institutions are studying the use of AI to optimize case analysis stages. Thus, not allowing its use is not advantageous for students, who need to be critically and responsibly prepared,” says the lawyer. In her perception, students performing better in essays and exams are those that develop the best prompts. “In order to ask the AI platform good questions and achieve the desired outcome, the problem to be addressed needs to be identified clearly,” says Godoy.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

In the first semester of 2024, computer scientist Rodolfo Azevedo, of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), delivered a pilot discipline introducing code-assisted programming in collaboration with UNICAMP colleague and electronics engineer Jacques Wainer. The students, all from the food engineering course, learned to program for the first time with ChatGPT as an assistant in the classroom, using Python language. “The aim was to teach programming concepts, with focus on developing the ability to break down a problem into smaller steps and resolving them. The means are always undergoing transformation, since the first punch cards,” says Azevedo.

In his opinion, using generative AI prompts students to think about more complex problems. “If we had to program from scratch before, which took more time, now AI writes code based on the instructions provided by the student, who can do a more in-depth analysis into errors — which always occur — and propose more elaborate solutions and improvements,” says the computer scientist, who stresses that the technology is already used by programmers from multiple corporations to optimize their processes. He also envisages other uses in the academic field. “These tools can reduce inequality for non-native English-speaking researchers, as they can ask AI to improve translations of their articles into that language,” he says.

Business administrator Ricardo Limongi, of the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), strives to teach students how to use these tools with a critical outlook. “I explained that I use them, and that they can also use them. That’s not cheating,” he observes. In the classroom, he opens AI platforms and shows the students how to compose a prompt, for example. In statistics, one of the disciplines he teaches, Limongi uses generative AI to help explain concepts that the students have difficulty in understanding, always overseeing the responses. “You get great analogies,” he says.

Author of an article on application of AI in scientific research, published in Future Studies Research Journal in April 2024, Limongi has been invited to lecture on the theme at universities, where he gives workshops presenting generative AI tools he has used with his students to optimize research processes.

Scientific journals

In addition to universities, the world’s most prominent scientific publishing houses have published rules on generative AI. In a September 2023 survey of more than 1,600 scientists in Nature, almost 30% of them stated they had used this technology to help in drafting manuscripts, with some 15% employing it to draw up funding requests. A study published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in January 2024 indicated that, among the 100 most prominent scientific journal publishers, 24% provided guidance on the use of AI, and of the 100 highest-ranked periodicals, 87% set out rules. Respectively, 96% and 98% of publishing houses and periodicals having guidelines prohibited the inclusion of AI as an author of articles.

The Springer Nature group constantly updates its rules and stipulates that generative AI use must be documented in the methods section of the manuscript. AI-generated images and videos are prohibited. Text reviewers may not use generative AI software when evaluating scientific articles, as they contain original research information. Publishing house Elsevier allows AI to be used to improve the language and legibility of texts, “but not to substitute essential author tasks, such as producing scientific, pedagogical, or medical insights, making scientific conclusions, or providing clinical recommendations.”

In Brazil, the Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) published a guide on AI tool and resource usage in September 2023. “In line with international publishers, one of the key points is that AI may not be considered as the author of a paper,” explains SciELO coordinator Abel Packer. The manual requires that authors declare when they use these tools — anyone hiding this is committing a serious ethical offense. However, the document encourages application of the technology to preparation, writing, review, and translation of articles. “In our view, five years from now, scientific communication will change completely, and the use of these tools will be omnipresent,” says Packer, who believes that the tools will soon take on an auxiliary role in assessing and revising manuscripts submitted to journals.

The story above was published with the title “Guidance on its way” in issue 342 of august/2024.

Scientific articles

LIMONGI, R. The use of artificial intelligence in scientific research with integrity and ethics. Future Studies Research Journal: Trends and Strategies. Vol. 1, no. 16. Apr. 2024.

GANJAVI, C. et al. Publishers’ and journals’ instructions to authors on use of generative artificial intelligence in academic and scientific publishing: bibliometric analysis. BMJ, Vol. 384. Jan. 31, 2024.

Republish