A decade ago, the world was shaken by the image of Aylan Kurdi, a three-year-old Syrian boy whose body washed ashore in Turkey after his family’s failed attempt to reach Greece. That haunting photo placed Europe’s borders at the heart of the global migration debate. But since then, many Global North countries have tightened their immigration laws even further—reshaping migration flows and repositioning Brazil in the geopolitics of international migration.

These findings are from the latest edition of a thematic migration atlas released this year by the University of Campinas Center for Population Studies (NEPO-UNICAMP). “Stricter rules are rearranging migration routes, making Brazil not only a migrant destination but also a gateway for those looking to reach the Global North,” explains demographer Rosana Baeninger, who led the project.

Scholars use the terms “Global North” and “Global South” to describe a political and economic divide in the world. The Global North generally refers to high-income, developed nations—including Western Europe, North America, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand. By contrast, the Global South comprises developing and low-income nations—primarily in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean—where poverty and inequality remain pressing challenges. China and India are also classified within the Global South.

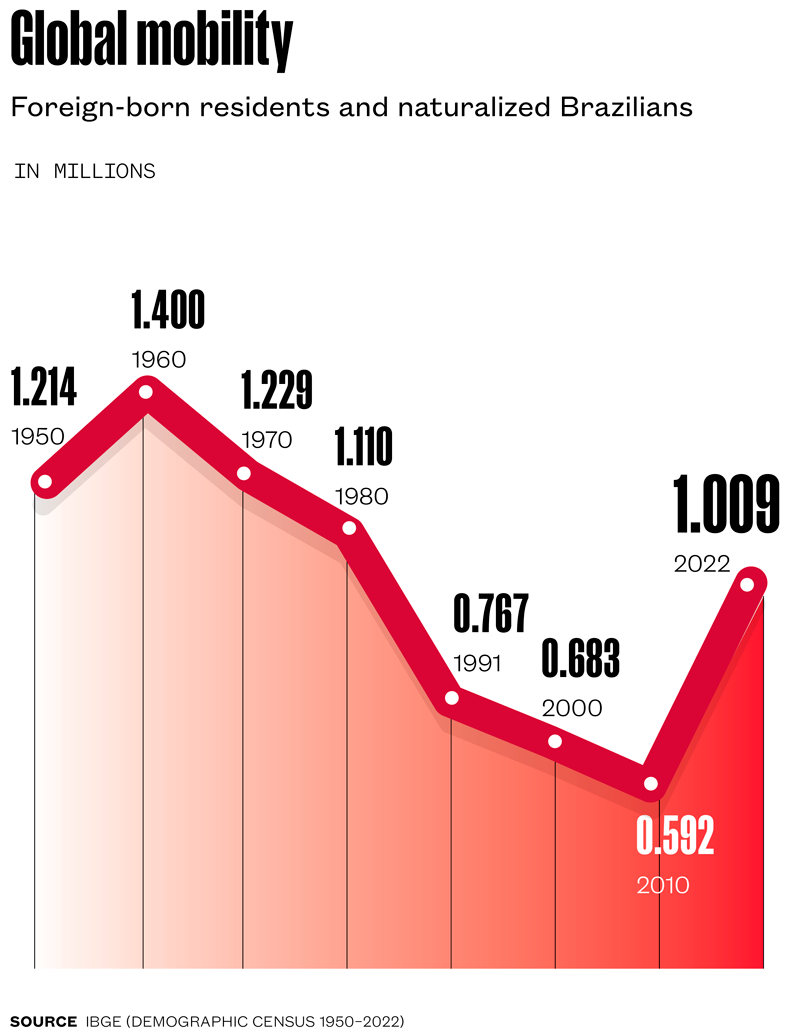

According to the most recent census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the number of foreign residents and naturalized Brazilians grew from 592,000 in 2010 to 1 million in 2022—an increase of 70% (see chart) and a sharp reversal of the long-term decline observed in previous decades. “Since the 1960s, the number of foreign residents in Brazil had been steadily declining,” notes Marcio Mitsuo, head of projections and estimates at IBGE.

But data from the International Migration Observatory (OBMigra)—a collaboration between the University of Brasília (UnB) and Brazil’s Ministry of Justice and Public Security—suggest even higher figures. Between 2010 and 2022, OBMigra recorded 957,000 new immigrant registrations and 327,000 asylum applications, not including naturalized residents. “If you combine the new registrations of immigrants and asylum seekers with the 600,000 immigrants counted in Brazil’s 2010 Census, as many as 2 million immigrants may now be living in the country,” estimates statistician Antônio Tadeu Ribeiro de Oliveira, who heads OBMigra.

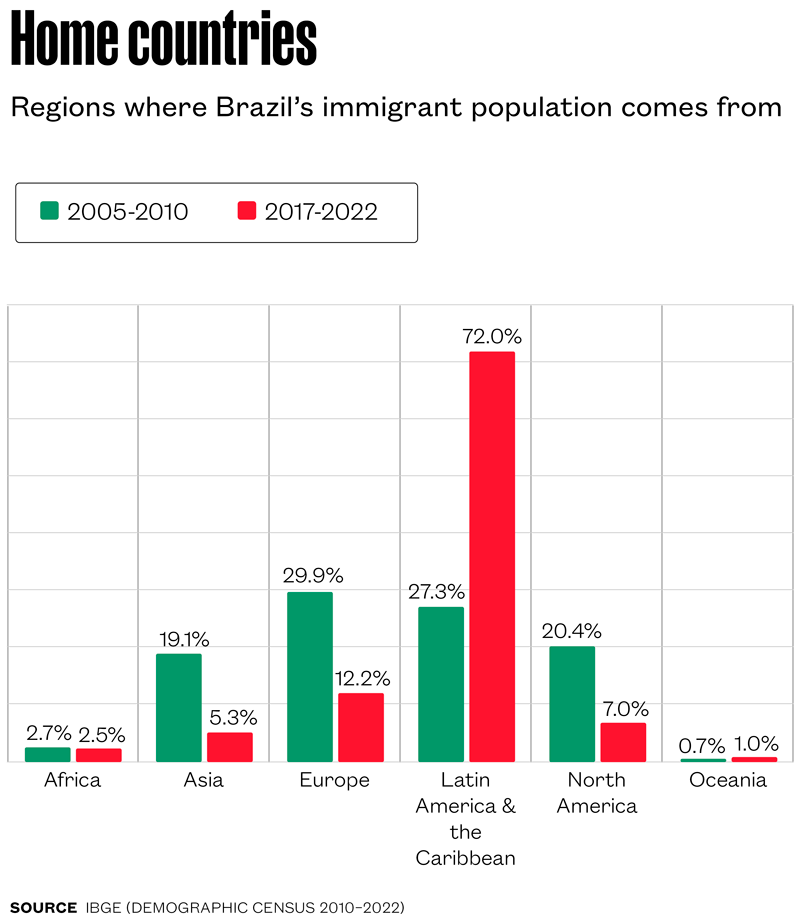

Up until 2010, Europeans made up the majority of Brazil’s immigrant population. Since then, however, migration has been led by Latin Americans (see chart on page 16). Census data show that of the roughly 1 million foreign-born residents currently in Brazil, 464,000 are from neighboring Latin American countries. Venezuelans represent the largest group at 271,000 people. Most of this influx has entered through the northern state of Roraima, followed by Amazonas. Beginning in 2016, both states saw a surge in arrivals as Venezuela plunged into a humanitarian crisis.

In response, Brazil’s federal government launched Operação Acolhida (“Operation Welcome”), a humanitarian program that provides documentation, vaccinations, and temporary housing to Venezuelan migrants. According to William Laureano da Rosa of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the program has already aided more than 800,000 Venezuelans. Roughly half have chosen to remain in Brazil. Of those, the majority—266,000 people—have been formally recognized as refugees, according to the 10th edition of Refúgio em números (Refugees by the numbers), a 2025 report published by Brazil’s National Committee for Refugees (CONARE) in collaboration with OBMigra.

The report shows that between 2015 and 2024, Brazil received 454,000 applications for refugee status, of which about 150,900 were approved. Refugee status is granted to individuals forced to flee their home countries because of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion—as well as those escaping severe and widespread human rights violations. After Venezuelans, the largest refugee groups in Brazil are Cubans (52,000), Haitians (37,000), and Angolans (18,000). These groups form the biggest contingent in Brazil’s refugee population, which now spans 175 nationalities.

According to both Rosa and Baeninger, the current migration wave can be traced back to 2010, when Haitians began arriving in Brazil after the earthquake that killed an estimated 300,000 people (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 265). Brazil’s federal government created a “humanitarian visa” giving Haitians a legal pathway to stay in the country (see glossary).

Baeninger explains that this marked a shift in Brazil’s stance within the geopolitics of international migration—a trend that grew stronger in the years that followed. In 2013, Brazil became one of the few countries worldwide to grant refugee status to Syrians escaping their nation’s civil war. More recently, beginning in 2021, the government extended humanitarian visas to some 15,000 Afghan migrants. “Many Afghans who arrived through São Paulo’s Guarulhos International Airport ended up staying there for weeks while waiting for housing,” recalls Rosa. “In some cases, they even chose to stay at the airport until they could arrange a new route—most often with the United States as their intended final destination,” he adds. Brazil has also begun receiving immigrants from countries with little to no historical presence in the country, including Nepal, Vietnam, and India.

When foreign nationals arrive in Brazil without a visa, they are detained at the airport as “inadmissible immigrants.” At that stage, they may submit a refugee application. Once the form is processed by Brazil’s Federal Police, they are granted provisional entry. The application is forwarded to CONARE, which evaluates each case and decides whether to approve or deny refugee status.

Moacyr Lopes Junior / Folhapress Haitian immigrants in São Paulo boarding a van to the Ministry of Labor to get their paperwork processed (2014)Moacyr Lopes Junior / Folhapress

Economist and demographer Luís Felipe Aires Magalhães, deputy director of the São Paulo Migration Observatory at NEPO-UNICAMP, explains that many migrants from the Global South come to Brazil specifically to obtain a residence visa or refugee status. When this is secured, they can then prepare for the next leg of their migration journey. “After that, many move on—often relying on smuggling networks to continue overland routes toward the United States or Canada,” says Magalhães.

Magalhães coauthored a chapter titled “Hoy me voy pa’l norte: ‘Crise migratória’ nas Américas e o Brasil como espaço de trânsito de migrantes internacionais” (Hoy me voy pa’l norte: Latin America and Brazil as staging posts for international migrants) in the book Migração e refúgio: Temas emergentes no Brasil (Migration and refugees: Emerging issues in Brazil), published by NEPO-UNICAMP last year. The study combined fieldwork in Brazil and Mexico with a desktop review of international migration data. Among those interviewed was a nun from the Catholic Migrant Pastoral Service, who has worked in the border states of Acre, Amazonas, and Roraima. She recounted helping many Haitians in the region who hoped to move on to the United States or Canada to join relatives.

Rovena Rosa / Agência Brasil | Kevin Carter / Getty Images Afghan refugees camping at Guarulhos International Airport in 2023 while awaiting shelter. A sign posted on the wall along the US–Mexico border (right)Rovena Rosa / Agência Brasil | Kevin Carter / Getty Images

Brazilian sociologist Julia Scavitti, who contributed to the research as part of her PhD at the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí in Mexico (completed in 2024), conducted ethnographic fieldwork in migrant shelters and in the streets of Tapachula. Sitting on Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala, Tapachula is a major transit hub for migrants—especially those heading north toward the United States. With funding from Mexico’s National Council of Science and Technology, Scavitti documented the experiences of many migrants who had begun their journeys in Brazil but were now in Mexico, preparing to continue on to the United States. The study—coauthored with geographer Caio da Silveira Fernandes of the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP)—notes that it was common to hear foreigners speaking Portuguese with varied accents, such as when parents communicated with their children.

One factor driving the rising number of immigrants in Brazil is economic opportunity. As OBMigra’s Oliveira notes, Brazil offers stronger job and income prospects compared to many other countries in the Global South. Supportive legislation also plays an important role. Brazil’s Refugee Statute (Law No. 9,474 of 1997) and its Migration Law (Law No. 13,445 of 2017) are grounded in human rights principles, Oliveira explains.

Under current law, foreign nationals are allowed to stay in Brazil while they process their paperwork, which can take up to two years. “Asylum seekers in Brazil receive a provisional document that lets them move freely throughout the country, take formal jobs, access the public health system (SUS), and enroll their children in school,” explains political scientist Julia Bertino Moreira, who heads the Research Group on Transnational and Other Migrations in the Twenty-First Century at the Federal University of ABC (UFABC) in São Bernardo do Campo. She contrasts this with practices in parts of Europe—such as Greece and Spain—where asylum seekers are often held in detention centers until a decision is made on their applications.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESPImmigrants from Guyana and the Democratic Republic of Congo teaching a course at SESCLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

Since 2016, University of São Paulo (USP) anthropologist Rose Satiko Gitirana Hikiji has been documenting the vibrant cultural and musical scene shaped by African immigrants in São Paulo. Her research as part of the FAPESP-funded thematic project, Local Musicking: New Pathways for Ethnomusicology, included interviews with artists from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Togo, and Angola. The project has produced four documentaries codirected with anthropologist Jasper Chalcraft of the University of Sussex in the UK. One of these films, São Palco – Cidade Afropolitana, won Best Feature at the 2025 Ecofalante Film Festival.

Hikiji also interviewed a troupe of Togolese musicians and dancers who left an international tour in Paraguay to resettle in São Paulo, seeking better living conditions. According to Hikiji, since 2015 they had been performing at festivals celebrating African cultural traditions—music, dance, and cuisine—hosted at venues across São Paulo, including Retail Social Service (SESC) centers and “Cultural Factories.”

Sociologist Willians de Jesus dos Santos, whose doctoral research explored the contemporary African music scene in São Paulo, highlights events such as the 2018 Gringa Music festival—organized by Congolese musician Yannick Delass at Al Janiah, a Palestinian-founded bar in the Bela Vista district—and Refúgios Musicais, a program hosted at SESC Belenzinho in the city’s east side. In 2024, Santos completed his doctoral dissertation at UNICAMP, supported by a grant from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP Congolese musician Yannick Delass at his home in São PauloLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

He notes that African artists in São Paulo are typically confined to niche markets. Most are invited to perform only in Black-related events—such as festivals during Black Awareness Month or venues dedicated to African music. And often, the opportunity for exposure replaces actual payment. “These musicians don’t want to be boxed into the label of ‘African artist,’ as that restricts their access to mainstream events and limits their potential earnings,” Santos explains. Many of the artists Santos interviewed hold university degrees, yet because they cannot make a living solely from music, they are often compelled to take low-skill jobs. “What’s more, several told me that Brazil was the first place where they personally experienced racism,” he adds.

Researchers interviewed for this article agree that Brazilian legislation does in theory offer legal security and protection for vulnerable migrants, but note there is a persistent gap between the laws on paper and their implementation in practice. “What we lack is a cohesive national policy to coordinate efforts across the federal, state, and municipal levels. Without it, immigrants will struggle to settle in Brazil,” argues Luís Renato Vedovato, a legal scholar at UNICAMP who in May completed a FAPESP-funded study on how multidimensional poverty—defined as deprivations beyond income alone—affects immigrants.

That gap may soon narrow with the creation of the National Policy on Migration, Refuge, and Statelessness, recently established by Brazil’s Ministry of Justice and Public Security (MJSP). According to Luana Medeiros, director of the ministry’s Migration Department, a federal decree is already being drafted to put the policy into effect. “The new framework is designed to improve coordination among federal, state, and municipal agencies while also expanding civil society’s role in shaping and scrutinizing programs for immigrants,” Medeiros concludes.

The story above was published with the title “Going South” in issue 355 of September/2025.[/bibliografia]

Projects

1. The concept of human dignity in relation to socially perceived needs: Vulnerabilities and minority rights (n° 22/15017-5); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Luis Renato Vedovato (UNICAMP); Investment R$55,048.50.

2. Local music: New paths for ethnomusicology (n° 16/05318-7); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Suzel Ana Reily (UNICAMP); Investment R$4,516,674.87.

Books

BAENINGER, R. et al. (eds.). Atlas temático: Observatório da emigração brasileira – Observatório das migrações dos países de língua portuguesa ‒ Migrações internacionais. Vol. 3. Campinas: Núcleo de Estudos de População Elza Berquó da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Nepo-Unicamp). 2025.

MOREIRA, J. B. & MENEZES, M. A. (eds.). Migrações transnacionais de refugiados e outras categorias de migrantes: Conceitos e experiências. Curitiba: Editora Appris. In press.

MAGALHÃES, L. F. A. et al. (eds). Migrações e refúgio: Temas emergentes no Brasil. Campinas: Núcleo de Estudos de População Elza Berquó da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (Nepo-Unicamp). 2024.

Report

JUNGER, G. et al. Refúgio em números 10ª Edição. Brasilia, DF. Observatório das Migrações Internacionais; Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública / Departamento das Migrações. 2025.

Republish