IncorUpon concluding his residency in pneumology, Rogerio de Souza decided to focus on an area that was ill-explored in Brazil until then: the study of the interaction between the lungs, the organs that draw life-sustaining oxygen from the air, and the heart, the organ that distributes oxygen throughout the body. In a little more than one decade of work, this physician, aged only 37 and a professor at the InCor Heart Institute of the University of São Paulo, has been helping us to better understand how arterial pulmonary hypertension, a marked increase of pressure within the blood vessels that carry blood from the heart to the lungs, comes about. Recently, Souza and his team found that this problem, considered rare in most of the world, is not that rare – at least not in Brazil and other developing nations, possibly, because of its connection with schistosomiasis.

IncorUpon concluding his residency in pneumology, Rogerio de Souza decided to focus on an area that was ill-explored in Brazil until then: the study of the interaction between the lungs, the organs that draw life-sustaining oxygen from the air, and the heart, the organ that distributes oxygen throughout the body. In a little more than one decade of work, this physician, aged only 37 and a professor at the InCor Heart Institute of the University of São Paulo, has been helping us to better understand how arterial pulmonary hypertension, a marked increase of pressure within the blood vessels that carry blood from the heart to the lungs, comes about. Recently, Souza and his team found that this problem, considered rare in most of the world, is not that rare – at least not in Brazil and other developing nations, possibly, because of its connection with schistosomiasis.

Until recently, it was generally thought that pulmonary hypertension only affects some 15 people out of every 1 million. Now, the InCor group has shown that this estimate, based on surveys conducted in France, may be valid in developed countries, but not in nations with more precarious healthcare, such as Brazil. Here, the problem is at least twice as common.

The difference between the ratio of cases found in Europe and in Brazil is due mainly to schistosomiasis. In developed countries, the disease’s most common form is idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, of unknown origin, whereas here – and most likely in a lot of the nations where the population lacks access to clean water and treated sewage – most cases arise due to a far more common illness: schistosomiasis, which affects some 200 million individuals worldwide (6 million in Brazil alone). From January 2006 to August 2007, Souza and his team assessed the vascular health of 65 people with a serious type of schistosomiasis – the liver and spleen kind – in which the eggs of the Schistosoma mansoni worm generate a severe inflammation of the liver and of the spleen, and found that 4.6% of them had developed pulmonary arterial hypertension, according to an article published in March of this year in the journal Circulation.

Based on the figures presented in this work, conducted jointly with French researchers from the University of Paris-Sud, in Clamart, the InCor researchers estimate that almost 13 thousand Brazilians suffer from schistosomiasis-related pulmonary arterial hypertension, a number several times higher than expected from the idiopathic form of the disease. If these data are valid for other countries in which schistosomiasis is a public health problem, there may be 400 thousand people in the world with pulmonary hypertension, a problem that develops slowly and that begins to manifest itself after the age of 40, in the form of extreme tiredness and breathlessness in the performance of moderate physical exercise, such as walking quickly for a few blocks. In its most advanced stages, the disease makes it impossible to even engage in day-to-day activities, such as walking from the room to the living room, brushing one’s teeth or combing one’s hair. “This form of hypertension affects a young population, of productive age, and may have a major social, economic and life quality impact on those who suffer from it and their relatives”, comments the Brazilian pneumologist, who, in 1997, created the pulmonary hypertension group of the InCor Pneumology Service.

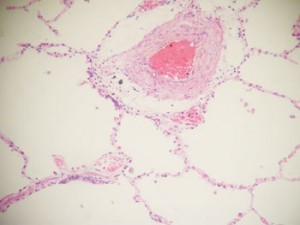

THAIS MAUAD/FMUSPThicker than normal pulmonary artery (pale pink ring), typical in this type of hypertensionTHAIS MAUAD/FMUSP

Under pressure

Caused by a narrowing of the blood vessels that come out of the heart’s right hand side, go past the lungs and reach the left hand side, pulmonary hypertension is far less common than the better known systemic arterial hypertension, one of the main causes of death in the Western World. But it is no less serious. Among people with pulmonary hypertension, the mean pressure within the artery that carries blood rich in carbon dioxide to the lungs is generally higher than 25 mm of mercury (mmHg) and may even go beyond 100 mmHg, whereas the normal level is lower than 15. Just to get an idea, the systemic blood pressure, i.e., the blood pressure in the rest of the body, is far higher, with a normal range of 80 mmHg to 120 mmHg.

Such high pressure indicates that the heart is facing more resistance to pump blood to the lungs, where it is oxygenated. The added effort causes the cardiac muscle to grow and the heart’s size to increase until it can no longer continue beating. If untreated, pulmonary hypertension can kill half of those who suffer from it within 2.5 years. “Luckily, the situation has been changing, thanks to drugs that help control pulmonary arterial hypertension”, says Souza.

Why schistosomiasis leads to a thickening of the pulmonary blood vessels is still unclear. According to Souza, there are signs that the Schistosoma’s eggs nest in the lungs, triggering inflammation that stimulates the cell walls of the blood vessels to multiply, thus reducing the space available for the blood flow. Regardless of the mechanism that drives cell proliferation – whether it is changes in the gene of the type 2 receptor of the morphogenetic bone protein (BMPR2) or the use of the appetite suppressant fenfluramine – the effects on pulmonary circulation are the same. The blood vessels become thicker, an alternation that doctors call vascular remodeling, blood pressure rises and the heart grows, causing tiredness at the smallest effort, as Souza and the InCor researchers observed.

In all cases, treatment consists of controlling the problem and keeping it from progressing, as there is still no cure for pulmonary arterial hypertension. The most commonly used drugs are those that cause a relaxation of blood vessels and that diminish vascular remodeling, such as the prostanoids, the antagonists of the endothelin receptors, and the inhibitors of the enzyme phosphodiesterase – in this last group, the one most often employed is sildenafil, the active ingredient in Viagra, used to treat male impotency. These drugs have enabled doctors to extend and improve the quality of the life of their patients, according to studies conducted by the InCor team.

In Souza’s opinion, the most efficient solution would be to fight schistosomiasis more effectively. “Even if one eliminates this and other illnesses at the heart of pulmonary hypertension over the next few years, their consequences will continue to be felt for several decades”, states the pneumologist, who participated in the determination of the international guidelines for treating the disease, to be released shortly. This is the case because pulmonary hypertension due to schistosomiasis and to other associated diseases develops slowly, over as many as 20 years, in ways that are not yet fully understood.

The Project

1. Cardiovascular response to exercise in pulmonary arterial hypertension (nº 07/03762-8); Type Regular Research Awards; Coordinator Rogério de Souza – InCor; Investment R$ 116,602.74 (FAPESP)

2. Evaluation of the muscles of the lower limbs in functional limitation due to pulmonary arterial hypertension (nº 07/04862-6); Type Regular Research Awards; Coordinator Rogério de Souza – InCor; Investment R$ 44,315.20 (FAPESP)