If biologist Carlos Roberto Ferreira Brandão had to save just one book from his library, it would be Sociobiology, a book that changed his life when he was finishing his undergraduate degree in the 1970s. After studying the scientific classification—or the classification of living things—of lizards, then molecular biology and biochemistry, he became fascinated by the social behavior of animals. Brandão wrote to the author, American ant specialist Edward O. Wilson (1929–2022), to tell him how impressed he and his colleagues were with the book. Wilson not only replied to the letter, he even invited Brandão to visit his laboratory at Harvard University during his master’s and doctoral degrees, both of which he studied at the University of São Paulo (USP) under the supervision of Paulo Vanzolini (1924–2013).

Age 69

Field of expertise

Entomology

Institution

University of São Paulo (USP)

Educational background

Bachelor’s degree (1977), Master’s degree (1980), and PhD (1984) from USP’s Institute of Biosciences

Published works

115 scientific articles

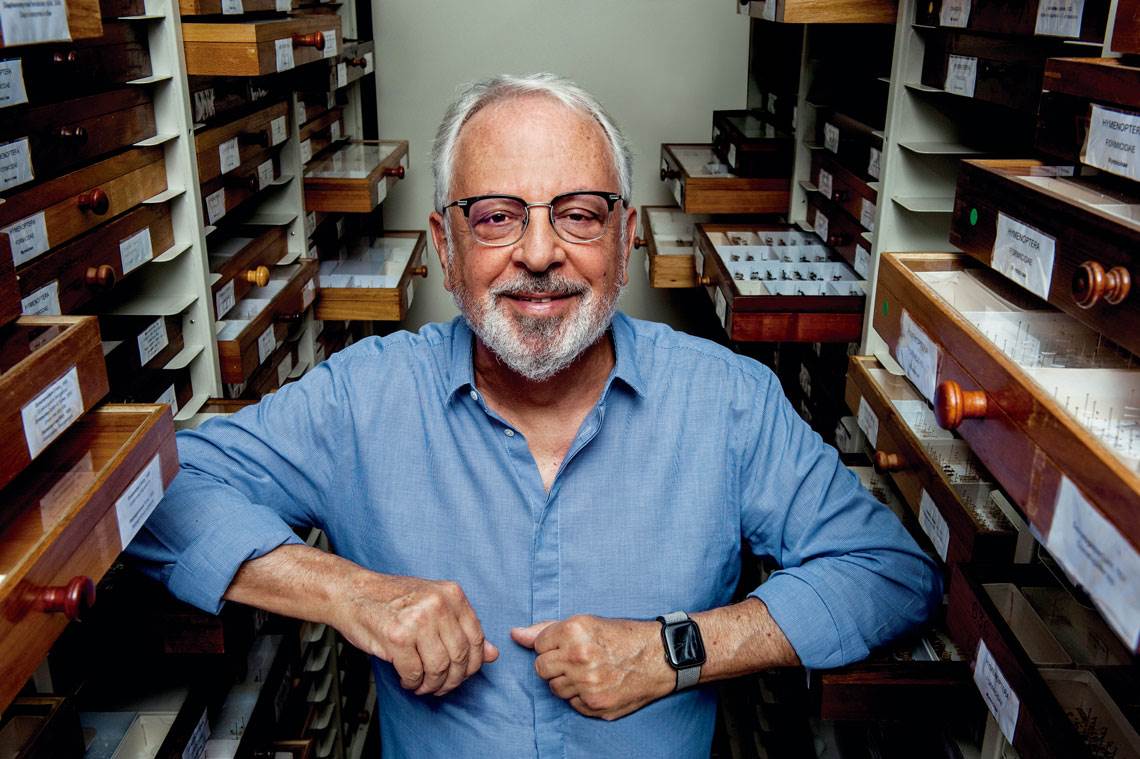

During his PhD, he was hired by USP’s Museum of Zoology (MZ) to manage its collection of ants, bees, and wasps. The collection of ants, which are his specialty, today includes 440,000 specimens stored in hundreds of cabinets in the center of his laboratory, surrounded by tables with old portraits, large wooden and metal model ants, and microscopes.

Having surveyed ant species in the Cerrado (wooded savanna), Atlantic Forest, and Caatinga (semiarid scrublands), Brandão became a museum manager, starting with the MZ in 2001 and then chairing the Brazilian chapter of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), a body associated with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). He was later appointed president of the Brazilian Institute of Museums (IBRAM), which manages the country’s national museums. Back in São Paulo, he became director of USP’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MAC). Brandão believes all museums, regardless of their specialties, are in essence highly similar, since they all work with memories, albeit expressed in different ways.

He is married to an engineer and has no children. On the morning of his interview with Pesquisa FAPESP, Brandão had visited an exhibition about black people in modernism at the Afro Museum in Ibirapuera Park, where he takes a 5-kilometer walk almost every day.

You were the coauthor of a paper published in the journal Ecology in February on the 1,500 known species of ants found in the Atlantic Forest. That’s a lot, isn’t it?

Yes, comparatively speaking, it’s a very high level of diversity. It’s greater than in the Cerrado, where we found about 700 species, and the Caatinga—a much more difficult environment for ants—where we found just 173 species in our most recent research. With the Atlantic Forest, something happened that was very instructive. In 1997, I applied for funding from the Biota-FAPESP program with the aim of increasing our knowledge about this biome. The response I received said something like, “Simply increasing knowledge is not science, it is curiosity. Come up with a scientific question so that by answering it, you increase knowledge.” So I thought about the following: the Atlantic Forest is a strip that goes from southeast to northeast with a gradient of latitudes. It’s the ideal environment to test the ecological hypotheses that biological richness is greater the closer you get to the equator. We mapped the conservation areas and collected samples from 26 regularly spaced points from Santa Catarina to Paraíba using the same techniques, in particular by taking ants from square-meter areas of leaf litter.

Did the initial hypothesis prove true in the Atlantic Forest? Does biodiversity increase nearer the equator?

In the Atlantic Forest, for ants, no. Diversity is high regardless of latitude, because of the humidity. A very small species called Stromigenys elongata, which is about 1 millimeter long, is one of the most abundant and common animals in the Atlantic Forest: it is found in 95% of the square-meter areas we sampled.

You were at Harvard for the first time while you were still studying your undergraduate degree. What was that like?

My father, José Henrique Brandão, was very good friends with Vanzolini. They studied medicine together and later married two women who were sisters. We lived next door to each other for many years. Vanzolini was studying reptiles on islands off the coast of São Paulo while I was doing an internship with him here at the museum. Herpetologist Ernest Williams [1914–1998], a professor at Harvard who had been a colleague of Vanzolini’s, came to teach a graduate course at USP’s Institute of Biosciences. He talked about a technique that was just beginning to be used called molecular biology, and suggested that a Brazilian student could study the technique of protein electrophoresis in starch gel in his laboratory. I introduced myself and that was that. I spent two months there, from January to March 1974, learning the technique from [Thomas] Preston Webster [1947–1975], a former student of Williams. I also learned to do karyotyping [chromosome analysis]. I took live lizards in a styrofoam box and analyzed them there. When I came back, I enrolled on USP’s undergraduate biochemistry course, taught by Walter Terra. I liked it a lot and decided to do a master’s degree in the same field. After discussing it with Vanzolini, I left the museum and went to the São Paulo School of Medicine [now the Federal University of São Paulo] to learn from Leal Prado and Eline Prado and their team. In the lab, we each worked on a different aspect of the metabolism of kinins—a group of substances that includes bradykinin, an antihypertensive drug discovered years earlier by [Brazilian physician] Maurício Rocha e Silva [1910–1983]. I thought the joint work we did in the lab—characterizing pH, molecular weight, and enzyme reaction rate—was really important, despite being descriptive. In the museum, I worked alone, getting my hands dirty with lizard scales. Since I still had to study one more discipline for my degree in zoology, I took a course on social animals taught by Paulo Nogueira Neto [1922–2019], one of Brazil’s most renowned specialists in bees. But because he was in Brasília creating SEMA [the Environmental Department], which later became the Ministry of the Environment, he was replaced by Vera Imperatriz Fonseca (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 284). The course was a watershed moment for me.

How so?

Fonseca introduced us to the main books on animal behavior that we should read and discuss. There were 15 of us, divided into groups of two or three. For me and for Lia Prado de Carvalho, who later became a researcher at the CNRS [National Center for Scientific Research] in France, it was Sociobiology by Edward Wilson, which had just been published. This book has two parts: the first is a catalog of social animal species, while the second seeks to explain the rules that shape sociality in different groups. Sociobiology reflected so much of what I was feeling and the things I believed in that I fell in love with the book. I wrote to Wilson describing what an impact it had, not just on me—the entire class was blown away by it. Unbelievably, he replied just a couple of weeks later. He wrote me a long letter saying how happy he was to find out that students in Brazil appreciated his book. He said I should work with ants and he could help me. And then he suggested something rather amusing: “The first step is you should go to the Museum of Zoology and find my friend Vanzolini.” They had been colleagues at Harvard.

Was he happy to see you again?

Not especially! “You’ve had your chance,” he said. “What are you back for?” So I explained: “I came for advice.” “Ok, sit down,” he said. I showed him my letter and Wilson’s, and he soon invited me back to the museum. I started a master’s project in 1977, funded by FAPESP, although none of the people who reviewed my proposal realized that it was not going to work: I needed to find a queen by establishing a colony, which is not an easy task. It took me a year to find an appropriately sized nest of the species I had chosen to study, and I only had two years to do my master’s degree. The first six months were a disaster, I brought ants to the lab and they ran away, the structure I created for them collapsed, the nest got disorganized. I faced a lot of practical difficulties in raising and observing the ants. And my supervisor was Vanzolini, who couldn’t help much because he worked with reptiles.

How did you overcome these problems?

Vanzolini recommended that I look for three people renowned for their work with ants: biologist Mário Autuori [1906–1982] from the Biological Institute, at the time part of the Zoological Foundation; Lúcia Prado [de Almeida Ferraz] from USP, who did her PhD on ant behavior with French ethologist Rémy Chauvin [1913–2009]; and Walter Hugo Cunha, a professor of experimental psychology at USP. They really guided me and helped a lot. Lúcia especially offered a lot of technical advice, suggesting that I simplify my research: “The more you complicate things, the more they can go wrong.” Walter Hugo Cunha’s course on behavioral observation at the Department of Experimental Psychology was wonderful: each student was given a closed Petri dish with a fly inside and had to describe the way they cleaned themselves. And Autuori suggested that I do a field project instead of lab work. As I remained at this impasse, Vanzolini suggested something: “Go and ask Wilson.” So I went to Harvard again. Wilson gave me a colony of a North American species of the genus Formica, which is not found in Brazil, to observe. I met with him for half an hour once a week. I had to show him my observations, raise any questions I had, and show him my plan for the following week.

What was Wilson like?

Cordial and friendly, but not particularly warm. I never met his family or went to his house, even though it was common for me and other students to visit the houses of other teachers. But he was the most stimulating person I’ve ever met. In our very first conversation, he said, “I want you to read this book,” and took a book on numerical calculus from a shelf, which had nothing to do with biology, and gave it to me. He thought we needed to learn how to break phenomena down into their parts and then model what could happen, which is what he did all his life. I still have the book to this day. I was there at the height of the controversy around Sociobiology. It was an ugly fight. Wilson worked on the sixth floor of a building attached to the Museum of Comparative Zoology called MCZ Labs. On the fourth floor was Richard Lewontin [1929–2021] and on the third floor was Stephen Jay Gould [1941–2002]. When the book came out, they published a scathing critique, saying that Wilson was sexist and racist, that biological bases of behavior had been an outdated topic since [Émile] Durkheim [French sociologist, 1858–1917] and that it contained major errors. Wilson always defended himself with poise, although the criticism he faced was not always so elegant. Time magazine’s cover on sociobiology came out at around the same time. It was he who put me on the ant trail. He told me that Watler Kempf’s collection had no curator. “If you study ants, you will be able to help a lot of people who are worried about this collection, and I can help you,” he said.

Who was Walter Kempf?

Walter Kempf [1920–1976] and Thomas Borgmeier [1892–1975] were two German-Brazilian Franciscan priests who specialized in ants. They organized a collection of ants that occupied a room at UnB [University of Brasília]. Borgmeier published the first catalog of Brazilian species, then began studying parasitic flies that use ants as their hosts. Kempf, who had already retired from the Franciscan order, continued studying ants while working as a volunteer professor at UnB. He was recognized nationally and internationally. But he died unexpectedly in 1976 during a visit to Washington DC for an entomology conference. The ant curator here at the museum, Karol Lenko [1914–1975], who collaborated with both priests to assemble the collection, died around the same time. So the collection was left unattended. I wasn’t a museum employee, but I was already a museum student, and I realized that if I did my PhD in classification, I would have a job there. I came back from Harvard, finished my master’s degree, and in 1977 I went to Brasília with a van driver from the museum to pick up the collection’s boxes. Along with it I brought back Kempf’s library and microscopes, which we still use today. The museum bought the collection with a grant awarded to Nelson Papavero by the CNPq [the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development], for what was basically a symbolic value. FAPESP paid for the transport. We had to make two trips, and each trip took two days to get there and two days to get back. Harvard’s museum made the link between taxonomy and behavior, to study this attribute from an evolutionary point of view. I was there at a great time.

In what way?

I took classes with the three greatest sociobiologists and evolutionary biologists I’ve ever known: Wilson, Bert Hölldobler, who wrote several books with him, and Bill Hamilton [1936–2000]. Every day at lunchtime, a visiting researcher gave a seminar. We took sandwiches and juice for a snack while we watched. It was paradise! That was also when I met Ernst Mayr [1904–2005], the writer of the great synthesis of comparative zoology. He was very reserved. I also met Bob Trivers, who later worked at Rutgers University. Ernest Williams, who was a friend of Vanzolini’s, took me to parties and invited me to have lunch with him and other teachers.

Did you face any obstacles in this paradise?

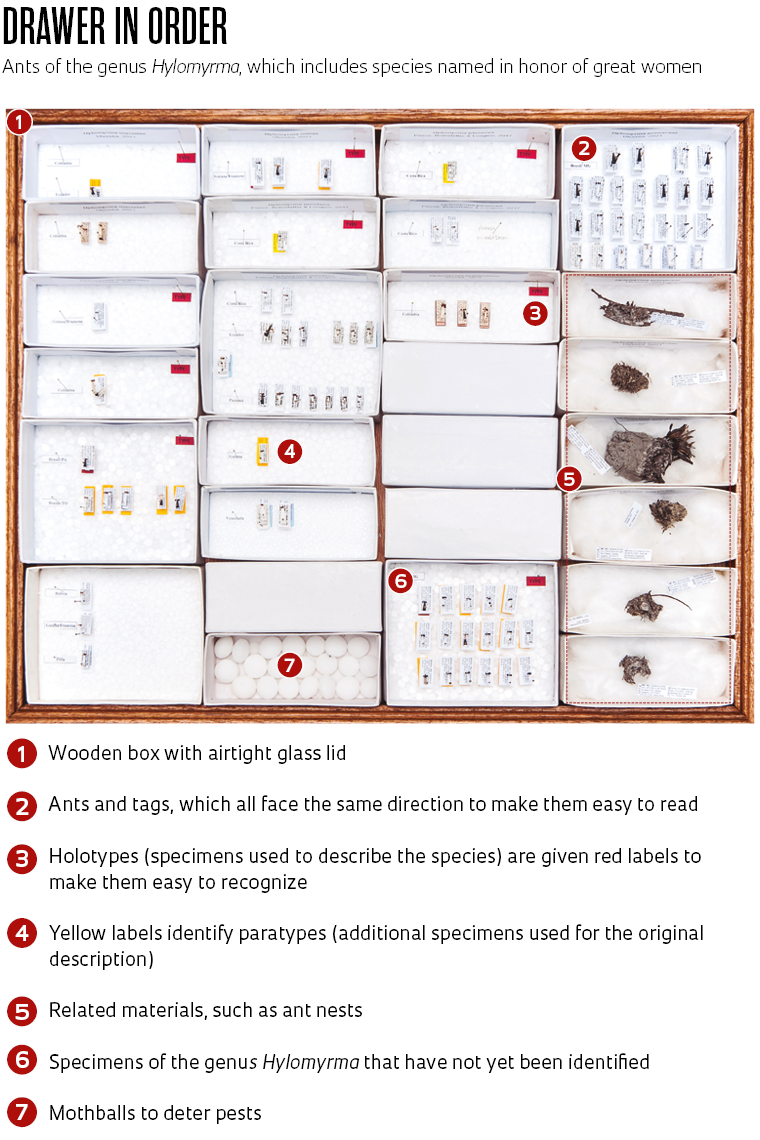

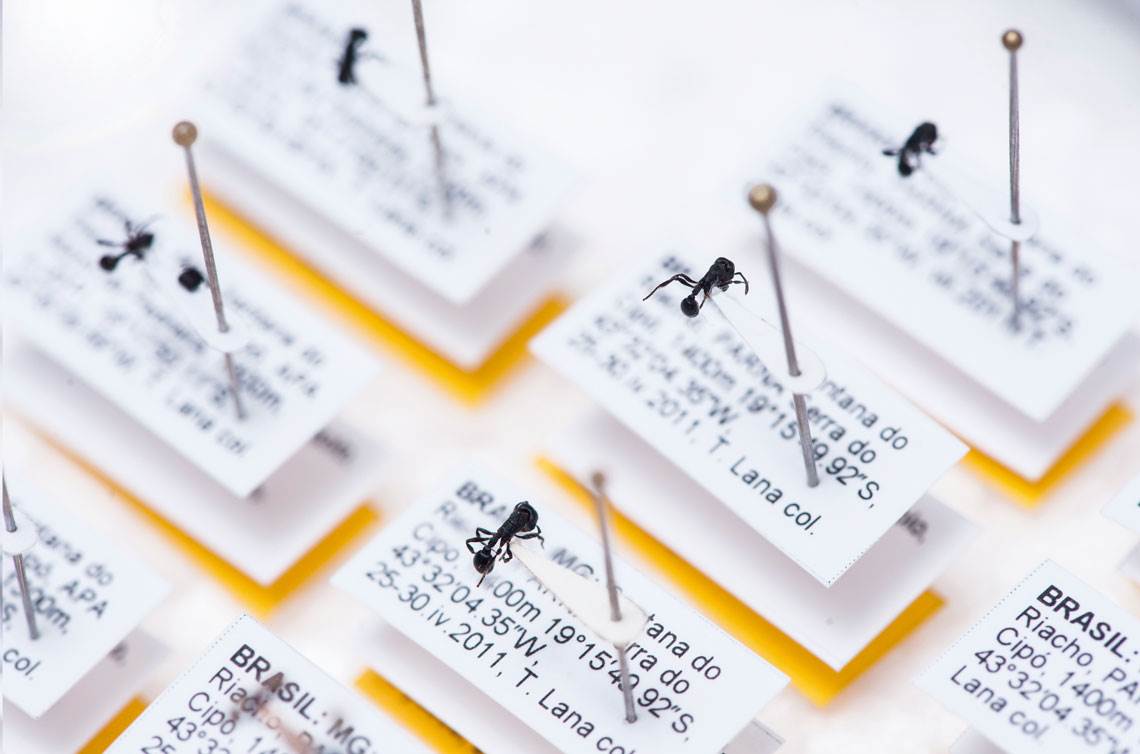

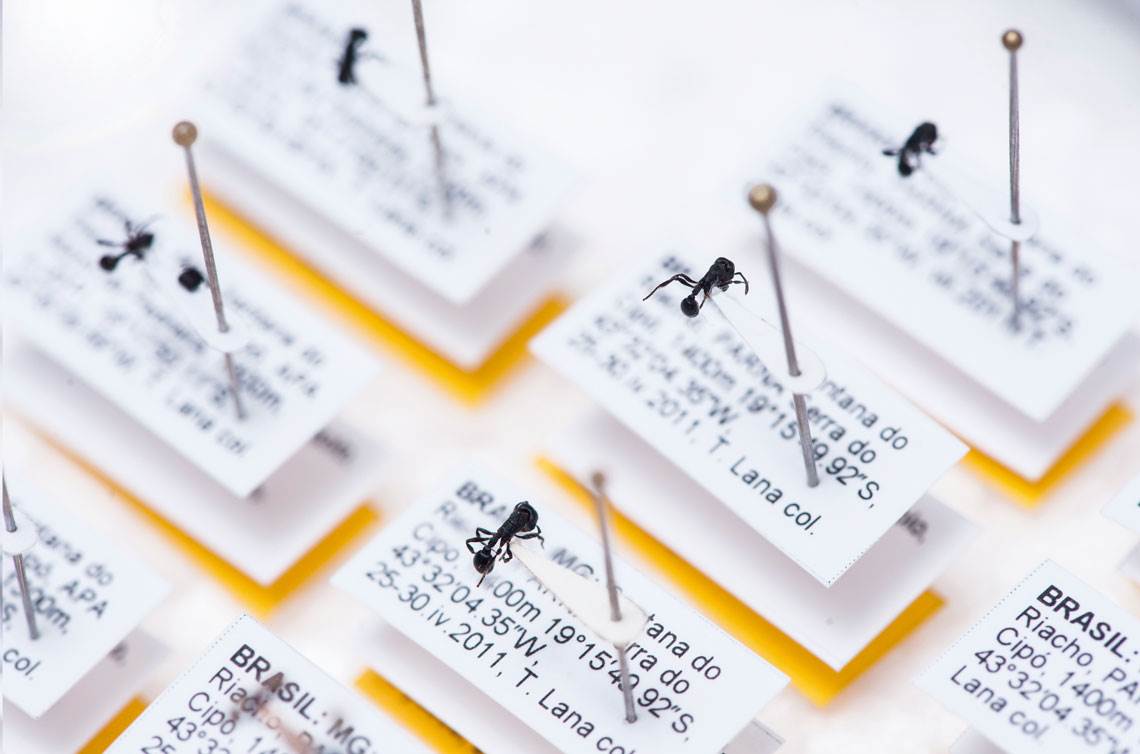

I didn’t know much about biology and I didn’t know much English either. I spent six months living in Brian Peterson’s basement—he was a renowned paleontologist who specialized in South American mammals. His wife Bia, a pianist, noticed that I didn’t speak English very well and made me a proposal. She said, “every day when you come home, tell me what you did, where you’ve been, what you ate, and who you met, and I’ll correct your mistakes.” So I learned English from a lady—I didn’t know any slang or curse words. After Harvard, I went to Cornell University to visit Bill Brown [1922–1997], a renowned specialist in ant taxonomy. He gave me some unofficial guidance for my PhD, during which I reviewed Megalomyrmex, a genus of large ants that can reach up to two centimeters in length. The genus encompassed about 30 species, but certain morphological characteristics suggested that it could be divided into four groups, each with distinct behaviors. That’s how I was able to unite behavior and taxonomy. Come and take a look [walks over to a drawer containing many Megalomyrmex specimens]. The males have wings, see? We can even observe behavioral characteristics in collection specimens. This specimen of the genus Dinoponera has a big abdomen and a funny story. When Borgmeier found it in 1930, he thought it was the first queen of the genus ever collected and published an article about it. Twenty years later, Kempf placed the specimen in a humid chamber—a box containing cotton and water—opened the abdomen laterally, and took out a coiled up one-meter-long parasite. It was a normal ant but with a parasite! To this day, no one has ever found a Dinoponera queen, a genus in which we now know that reproductive duties are assumed by a worker from the colony.

Is it possible to compare the collections from the two locations?

At Harvard, most boxes in the ant collection contain just one specimen. It’s a worldwide collection and includes many type specimens [specimens used to describe a species]. Our collection, meanwhile, focuses on the Neotropical Region—from Mexico to Argentina—with an emphasis on Brazil. We have boxes of various sizes that hold many specimens of each species and from many locations, providing a good sample of the diversity and variation within each species. We have 440,000 specimens, just of ants. It’s the largest neotropical collection in the world.

What did you do after you brought the priests’ collection back here?

I was hired by the museum while still studying my PhD to take care of the collection. I had to reorganize everything. I put ants from Kempf’s collection together with those from the museum when they were the same species. I found several errors, so I was fixing those one by one as I worked. Then I started doing surveys in the Cerrado to complete Kempf’s studies. I spent 10 years working in the Cerrado, which I think is a wonderful biome.

Did you enjoy fieldwork?

So much. What I loved most was leaving the museum with a van full of equipment and five students, and spending a month in the bush collecting and observing the behavior of the ants. I tried to apply a quantitative technique based on what I had already collected to estimate the expected number of species and distribute the collection time. It’s the big question in fieldwork: how much should I collect from each location in order to obtain a good representation and to be able to look for the next place or environment? In one location, for example, I follow a path and collect maybe 50 samples—one every 10 meters. Or we scrape a certain number of soil, leaf, and twig samples, sieve them and then put the mixture in a mesh bag, inside a cloth bag, with a small cup of water and cotton at the bottom. The ants seek out the moisture in the cotton and then we put them in alcohol and bring them back to the lab. I remember once collecting samples with some students, I was face down on the ground threading a fishing line through holes to see the tunnels and chambers. Suddenly I saw something out of the corner of my eye. It was a queen of a very rare species, which I was seeing for the first time: Basiceros scambognathus. I brought it back to the lab and described the workers that were born from the queen, the males, the eggs, the nest, everything. But with each trip we saw more deforestation, heard more chainsaws. I saw the Cerrado intact and I saw it being destroyed over 50 years. Today, outside the conservation areas, most of it is soy farms.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPEach specimen is placed at the end of a strip of paper above its identification. It is thus easy to see if any part of the specimen falls offLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

What is the Museum of Zoology’s ant collection like?

It is well maintained, but by few people. The university hasn’t hired any new technicians for eight years, while offering voluntary redundancy packages to those it had. I’m returning to the museum now, I haven’t been there much since 2015—master’s and PhD students and postdoctoral researchers have been helping keep the collection organized.

You’ve also been a museum manager since 2001, right?

Yes, I was head of the Museum of Zoology’s laboratory, entomology section, and scientific division until 2001, when I was appointed museum director. The MZ has always been a highly recognized research body, but it was not truly a museum. The exhibitions ware based on old concepts: cabinets of amphibians, reptiles, or mammals that didn’t do justice to the modernity of the laboratory and the research it was doing. Visitor numbers were low and mostly only resulted from the affection the local population of the Ipiranga neighborhood had for the museum. I hired the museum’s first educator, Márcia Fernandes, and the first professor for the Culture and Extension Division, Elizabeth Zolksak, who was later replaced by Maria Isabel Landim. When my term ended four years later, the museum was a recognized institution in the field of museology.

Did you fully understand museology at the time?

No, but I grew up in an environment that favored a mixture of science and art. My father was a doctor, my great-aunt was a biologist at the museum, and my uncle had a cicada collection. Sérgio Buarque de Holanda [historian, 1902–1982] and Arnaldo Pedroso d’Horta [painter, 1914–1973] frequently visited my house and Vanzolini’s (we were neighbors). When I met Sérgio’s son Chico, he was just a boy—he hadn’t started making music yet. When I was little, my uncle, who was a Swiss naturalist, took me to the São Paulo Art Biennial. I always liked museums. When I was a young child I visited MASP [São Paulo Museum of Art] on Rua 7 de Abril, in the center of the city, because I was at the Caetano de Campos school, which at the time was located in the nearby Praça da República. As director of the Museum of Zoology, with the support of the then dean Adolpho Melfi, I renovated and restored the external facade, opened a new exhibition, and increased visitor numbers from 200 a year to 100,000. In 2005, I was invited to take over the role of president of the Brazilian chapter of ICOM and I began representing Brazil at annual meetings at the UNESCO headquarters. In 2007 I was appointed to ICOM’s executive board and started a campaign to host the international conference, held every three years, here in Brazil. In 2013, the conference was held in Rio de Janeiro, with 3,000 participants from 110 countries and related activities at 57 museums in the city. In 2015, the then Minister of Culture Juca Ferreira invited me to preside over IBRAM, now overseen by the Ministry of Tourism, which is responsible for all legislation in the area and for managing Brazil’s 30 national museums. And I moved to Brasília.

The training of personnel that Ibram did so brilliantly has died. Iphan is being dismantled

How was the experience?

It was a fantastic learning experience. I visited all 30 of IBRAM’s national museums, from the island of Alcântara in São Luís, Maranhão, to Missões in Rio Grande do Sul. I reaffirmed my belief that every museum is equal, regardless of the object it studies, exhibits, or preserves. Museums are par excellence multidisciplinary spaces involving museologists, historians, biologists, art specialists, art historians, conservators, and digitizers. In essence, museums work with memories, expressed in different ways. When Temer’s administration began in 2016, I didn’t want to stay, so I returned to São Paulo. What I see today is that our national museums have been abandoned. All the training of personnel that IBRAM did so brilliantly has died. The National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute (IPHAN) is being dismantled. When I returned to São Paulo, the MAC had no director and no professors were interested in taking over. In 2016, the then dean Marco Antonio Zago [current president of FAPESP] asked me to apply. I did so based on this belief that all museums are equal. What mattered was my experience managing various types of museums. I applied some museological techniques, such as developing a strategic plan in which each sector submits proposals on what it would like to achieve in the next five years.

Was there any resistance to you taking on the role?

No. There was perhaps some mistrust. The first thing I did was to encourage working together with MAM [São Paulo Museum of Modern Art]. Felipe Chaimovich was the curator at the time. We put on a joint exhibition to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the founding of MAM, from which MAC was derived. In 2020, another dean, Vahan Agopyan, offered me another challenge, this time at EDUSP [USP’s publishing house]. I resisted a little, but eventually accepted. There I also came up with a strategic plan and studied how the space was used based on my experience at museums. I was president of EDUSP for a year and a half, until March.

What’s next?

My plan is to stay here at the MZ. I’m 69 now and will retire soon. I no longer have the energy to go on field trips or manage big projects. It’s time for new blood.

Do you already have a successor?

Yes. Gabriela Camacho, an excellent researcher who specializes in ants, was chosen via a competitive hiring process. During her doctorate, she was supervised by a former student of mine, Rodrigo Feitosa, now a professor at UFPR [Federal University of Paraná]. She returned early from a postdoctoral fellowship at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin to take over the position on June 14. But I’m not going to stop visiting the museum and participating in research—I can continue as a volunteer professor. I still have a lot of work to do with my students and a lot of material to study in the collection. The museum is a wonderful environment and remains highly stimulating.

Republish