In a scene from Federico Fellini’s (1920–1993) I Vitelloni (1953), a drunken character floats a wild idea to his friend: leave it all behind and start over in Brazil. Fueled by exoticized fantasies—embodied by figures like Carmen Miranda (1909–1955)—mid-century Italian filmmakers saw Brazil as a tropical utopia: sensuous, joyful, and rich in natural beauty. It became a canvas for dreams that would be impossible on a continent devastated by Word War II (1939–1945). Decades later, Chico Buarque’s exile in Rome between 1969 and 1970 began to unravel that fantasy, according to Luca Bacchini, a Brazilianist scholar at Sapienza University of Rome.

Bacchini, who has spent over 20 years studying historical and cultural ties between Brazil and Italy, has devoted much of his research to Buarque’s Italian connections. In the 1970s, Buarque released albums in Italy, teamed up with legends like Ennio Morricone (1928–2020), and saw his songs sung by stars like Sergio Endrigo (1933–2005) and Mina Mazzini. The song “A banda,” for instance, was reworked into Italian twice, with one version notably twisting the song’s meaning to fit Mazzini’s artistic persona. “When Chico arrived in Italy during his self-exile, record companies crafted strategies to fit him into a market steeped in caricatured views of Brazil,” Bacchini says. “They were determined to make him fit the mold.” But Buarque’s work didn’t play to those fantasies—and that, Bacchini argues, is precisely why it helped to break them down. “He paid a price for it,” Bacchini adds. “He was misunderstood by a market that, at the time, was used to consuming a very specific version of Brazilian culture.” Bacchini is now working on two books: one on Buarque’s Italian exile, the other on his literary career.

Just as with his music career, Buarque faced resistance in gaining literary recognition in Italy. “In Italian academia, Buarque wasn’t taken seriously as a Brazilian literary figure—he was seen as a musician who dabbled in fiction,” Bacchini explains. He draws a parallel with Vinicius de Moraes (1913–1980), who, to this day in Italy, is often remembered more as a songwriter than the poet he was. In Buarque’s case, that perception began to shift in recent years, especially after he won the Camões Prize in 2019. “The literary canon is still stiff in Italian academia,” Bacchini says. “But more students are finding their way to Brazil—and to Portuguese—through Chico’s novels.”

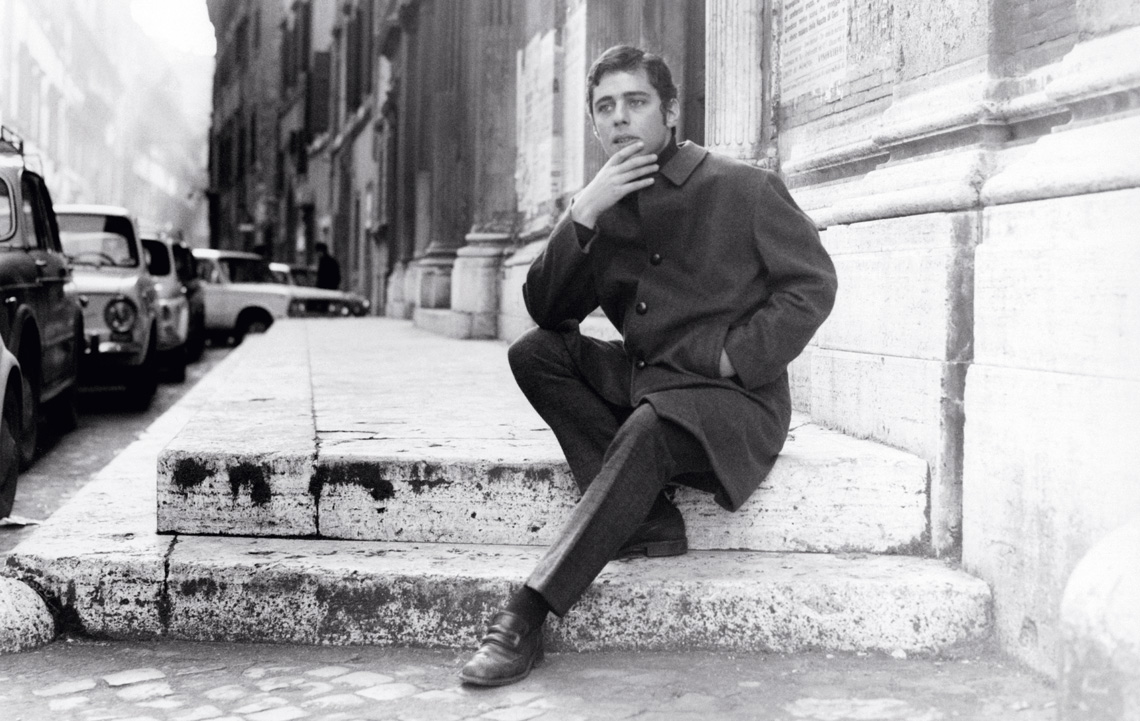

Mondadori Portfolio / Getty ImagesThe author sitting in front of a church in Rome, Italy, during exile in 1969Mondadori Portfolio / Getty Images

Bacchini now teaches a full-year course at Sapienza University in Rome devoted entirely to Chico Buarque’s work. “Among younger students, Chico the novelist is almost more famous than Chico the singer,” Bacchini notes. “Some of them have never heard ‘Apesar de Você’ or ‘Cálice,’ but they’ve already read Budapest or Bambino a Roma (Child in Rome).” He recalls that between 1953 and 1955, Chico’s father, historian and sociologist Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (1902–1982), held the first chair of Brazilian literature at Sapienza.

Six of Buarque’s novels have been translated into Italian, including Spilt milk, Budapest, and Essa gente (These people). In Brazil, he began writing while still a teenager, publishing in his high school newspaper in São Paulo. In 1966, one of his short stories appeared in the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo. His first long-form work, Fazenda modelo (Animal farm), came out in 1974. But it wasn’t until 1991 that his breakout novel Turbulence appeared, launching a fiction career with Companhia das Letras, which has since published seven of his eleven books. His novels have been translated into Spanish and English as well, including Turbulence, Benjamin, and Budapest.

In the US, Chico Buarque’s literary work has helped make his broader oeuvre better known, says Charles A. Perrone, professor emeritus in the Spanish and Portuguese Department at the University of Florida. Perrone has been studying Buarque’s music since the 1970s. He notes that in the US, Buarque is less widely recognized as a musician compared to Milton Nascimento, Caetano Veloso, or Gilberto Gil—but the novel Turbulence began to change that. “Turbulence (Pantheon, 1993) was warmly received by critics in the US and UK,” Perrone explains. “And beginning in the late 1990s, translated essays by literary critic Roberto Schwarz helped deepen interest in Buarque’s fiction.” Perrone, who authored a 2022 book exploring the 11 tracks on Buarque’s 1978 self-titled album, notes: “American audiences often miss the poetic subtlety in Chico’s songs. But his prose has a bigger appeal—especially outside the academic bubble.”

CourtesyBuarque’s novels subtly embed the tangled roots of Brazil’s social structureCourtesy

In Portugal, however, Buarque’s reception followed a different trajectory. Clara Rowland, a professor at NOVA University Lisbon, says Buarque has been a household name in Portugal since the 1960s, with generations growing up on his music. Rowland, who teaches in the Department of Portuguese Studies, says that bond became especially clear in 2019, when Buarque was awarded the Camões Prize, with her among the judges. The Camões Prize, founded in 1989 by the governments of Brazil and Portugal, is considered the highest literary honor in the Portuguese-speaking world. “I witnessed the outpouring of emotion when the news was received in Portugal. The response was explosive,” Rowland recalls in an interview with Pesquisa FAPESP.

For Rowland, the soundscape—music and voice in particular—is essential to Buarque’s writing. In his latest novel, Bambino a Roma, which weaves together memories—real and imagined—of a Roman childhood, a pivotal moment comes when the narrator reconnects with a childhood friend by singing a samba in Italian. “Music acts like a thread,” she says, “pulling the characters back to themselves, stitching together shards of memory.” Rowland sees the book, published last year in Portugal and Brazil, as a blend of memoir and reflection on the craft of writing. In one scene, the narrator pedals through Rome with a worn-out map. When it falls apart, he sketches a new one on the back—a personal version of the city, a Rome, as he puts it, “built from the inside out.”

Rowland also argues that Buarque has few equals when it comes to crafting songs—an art he’s honed steadily for decades. “His fiction, though, emerges from a riskier space,” she observes. “It’s exploratory—filled with missteps, experiments, and returns. The uneven quality of his texts is part of this process of exploring writing, which his books, in fact, often acknowledge.”

Buarque’s fiction emerges from a risky space. It’s exploratory—filled with missteps, experiments, and returns

Chico Buarque’s fiction was the focus of a special edition of the journal Literatura e Sociedade, published in late 2024, featuring essays by scholars from diverse fields examining his literary trajectory. Edited by Maria Augusta Fonseca, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities (FFLCH-USP), the issue places Buarque in a lineage that begins with Machado de Assis (1839–1908) and continues through Brazilian modernists like Mário de Andrade (1893–1945) and Oswald de Andrade (1890–1954). She argues that novels such as Spilt milk (2009) converse with classics like Machado de Assis’s The posthumous memoirs of Brás Cubas (1881) and Dom Casmurro (1899), and also with Oswald de Andrade’s Memórias sentimentais de João Miramar (Sentimental memoirs of João Miramar; 1924). Though varied in theme, these works, Fonseca suggests, are all structurally fragmented and challenge readers to piece together meaning in worlds marked by broken connections. “Buarque’s prose stands out for its musical pacing,” Fonseca says. “And for the humor that often undercuts the storytelling.”

One of the defining features of Buarque’s fiction, she notes, is its engagement with history. “His books tackle the dilemmas of modern Brazil head-on, while never losing sight of the deeper historical strata that shape them,” Fonseca explains. “They show how the country remains trapped in foundational contradictions—poverty, inequality, violence.” This is particularly evident in Spilt milk, where the narrator—a centenarian on his deathbed—dictates the story of his life to a nurse. “He becomes a tyrant not just of narrative but of history,” she says, “embodying the vices and entitlements of the elite class he represents. He reminisces with little critical distance, celebrating stances that today feel deeply disturbing—like a defense of slavery and open classism.” Fonseca argues that while the narrator appears to be simply recounting his life story on the surface, the subtext delivers a pointed critique of Brazilian society. “In the novel, Buarque discreetly weaves in elements that expose the complexity of the country’s social fabric, including familial ties between slave owners and the enslaved, which appear subtly embedded in the narrative. It takes a careful reader to pick up on these layers,” she notes.

MMaranhão / FolhapressBuarque (center) at the 2023 Camões Prize ceremony, held at the Palácio Nacional de Queluz, Sintra, PortugalMMaranhão / Folhapress

Denilson Soares Cordeiro, a philosophy professor at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), offers a reading of Buarque’s fiction through the lens of literary critic Antonio Candido’s (1918–2017) notion of “radicalism.” In Candido’s framework, radicalism is a historically grounded stance of social and political critique. “In his literature, Chico expresses a radical mode of being a writer,” Cordeiro says. “But it’s a middle-class radicalism, constrained by the limits of his own social position.” This tension surfaces in Anos de chumbo e outros contos (Years of lead and other stories; 2021), a collection that confronts themes like police and military violence, sexual assault, madness, and social decay. One story follows a 14-year-old girl whose parents sell her to her uncle, a paramilitary thug. “And yet,” Cordeiro notes, “the child narrator tells the story with disturbing serenity.” Cordeiro observes that this subdued tone recurs throughout the book—extreme violence is relayed with a strange detachment. “This distance,” he argues, “marks the outer edge of Buarque’s radicalism. It signals the political limits of his literature.”

Fiction offers Buarque a space for aesthetic and political exploration of themes that had long simmered in his songwriting, says sociologist Marcelo Ridenti of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). Ridenti argues that Buarque’s novels, particularly Benjamin (1995), explore the tension between subjective and historical time. “In Benjamim, the narrative revolves around one man’s obsession with a lost love,” Ridenti explains. “But the real subject is time—not chronological time, but time as it’s experienced by the characters.”

This approach, he says, opens space to reflect critically on the erosion of the collective dream that once cast Brazil as “the country of the future.” That dream, Ridenti argues, has faded over recent decades, as collective visions for transformation have lost traction. “Even left-wing governments have failed to offer real alternatives to a society dominated by consumption and labor exploitation,” he says. Ridenti believes Buarque captures this crumbling of historical consciousness. “He shows how the utopian energy of the 1960s and 1970s has unraveled,” Ridenti says, “leaving behind a feeling of temporal drift.”

The story above was published with the title “Global audiences” in issue 351 of May/2025.

Scientific articles

CORDEIRO, D. S. Matéria brasileira e radicalismo em Anos de chumbo e outros contos. Revista Literatura e Sociedade. Romance. Conto. Memória. Teatro. Homenagem a Chico Buarque. Vol. 31, no. 40. 2024.

RIDENTI, M. Benjamim, Benjamin. Romance, história e melancolia de esquerda. Revista Literatura e Sociedade. Romance. Conto. Memória. Teatro. Homenagem a Chico Buarque. Vol. 31, no. 40. 2024.

Book

PERRONE, C. A. Chico Buarque’s first Chico Buarque. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.