Intense temperature fluctuations increase the risk of death, especially for unprotected people, such as those who are homeless, or those who are more vulnerable and sensitive to temperature changes, like young children and the elderly. Temperatures of around 30 degrees Celsius (°C) are already enough to cause heat exhaustion in manual laborers, with intense sweating, heavy breathing, and a rapid pulse, along with dizziness and mental confusion. At around 40 °C, even those at home, sitting on the sofa, can feel unwell, displaying the same symptoms, and may require hospitalization if the environment is not air-conditioned. The heating of the body leads to the dilation of blood vessels, which reduces blood pressure, causing the heart to work harder to deliver oxygen to the organs. The body also loses fluids and minerals, which aggravates the situation. Exposure to low temperatures for a few hours, on the other hand, usually causes the opposite changes, but with similar health effects. The blood vessels contract, concentrating the blood in the internal organs. Blood pressure and heart rate increase, and if the body is not warmed up and brought back to equilibrium, the cardiovascular system can collapse.

“The human body functions well within a narrow internal temperature range, around 1 degree above or below 36.5 °C. Outside this range, issues start to occur, which are more serious for children, the elderly, and people with preexisting illnesses,” says meteorologist and physician Micheline Coelho. With a master’s degree and PhD in the field of her first undergraduate degree, she later graduated in medicine and works as a collaborative researcher for the Experimental Environmental Pathology Laboratory (LAPAE) of the School of Medicine at the University of São Paulo (FM-USP) and at Monash University in Australia. In partnership with pathologist Paulo Saldiva, coordinator of LAPAE, she researches the relationship between atmospheric conditions and human health.

Saldiva and Coelho are part of an international research network that, over the last decade, has begun estimating the impact of the hottest and coldest days on people’s health and the economy. In a study recently published in the December print issue of the journal Environmental Epidemiology, the two Brazilians and researchers from nine other countries calculated the proportion of deaths that can be attributed to extreme heat and cold in 13 Latin American countries, as well as the three French overseas territories on the continent, and the financial losses they represent.

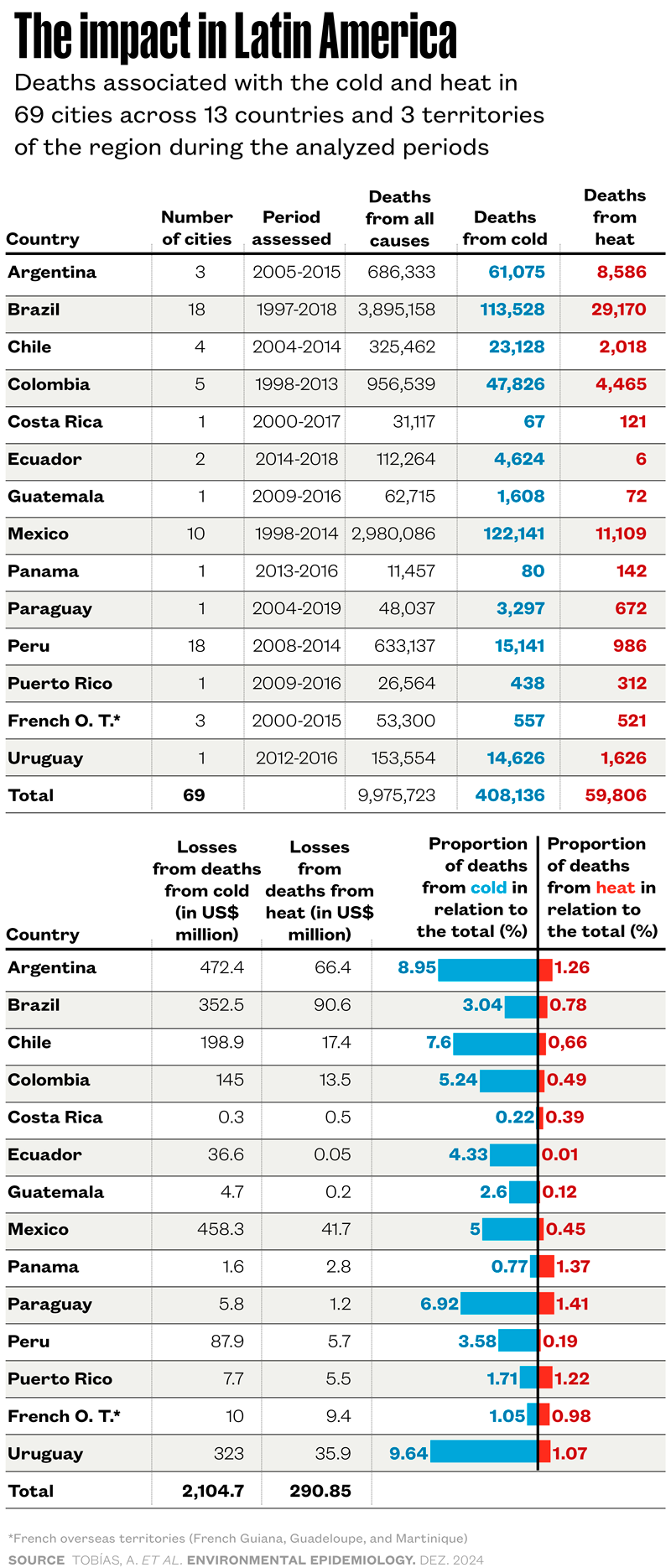

The 69 locations assessed are situated in countries ranging from Mexico to Chile, including Brazil. At least 408,136 people died because of the cold and 59,806 due to heat between 1997 and 2019 in these locations. The deaths from low temperatures account for 4.1% while those associated with high temperatures account for 0.6% of the 9.98 million deaths recorded in these cities during the period. Together, these fatalities caused a loss of around US$2.4 billion per year, calculated based on the estimated value of one year of life and on the number of years that each person would have lived if they reached the average life expectancy for their population. The losses related to cold varied from US$0.3 million per year, in Costa Rica, to US$472.2 million per year, in Argentina. Associated to fewer deaths, heat caused annual losses that ranged from US$0.05 million, in Ecuador, to US$90.6 million in Brazil (see table).

Brazil contributed with one of the highest numbers of locations and the longest historical series. In Brazil, in 18 cities where more than 30 million people live (including 12 state capitals), there were 3.86 million deaths from 1997 to 2018. In this 22-year period, 113,528 deaths resulted from the cold and 29,170 from the heat, with annual losses totaling US$352.5 million in the first case, and the already mentioned US$90.6 million in the second case. “One problem in Brazil is that, in general, houses, schools, hospitals, and many workplaces are not prepared to face either extreme cold or excessive heat, which are likely to become more common in many parts of the country as a result of climate change and changes to the urban environment,” says the physician and meteorologist.

Deaths are merely the most extreme and visible effect of temperature variations. Cold and heat, however, cause economic losses and affect quality of life. In a previous study, published in 2023 in the journal Science of the Total Environment, Saldiva, Coelho, and colleagues calculated the economic losses at nearly US$105 billion, in 510 Brazilian cities, resulting from working in unsuitable temperature conditions (very hot or cold) between 2000 and 2019 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 331).

In studies like these, the temperatures associated with deaths are those that differ most from the value considered comfortable for the population of each city. This is known as the minimum mortality temperature (MMT): the optimal average temperature, calculated based on values measured throughout the day, at which the lowest number of deaths is recorded. In the study from the December issue of Environmental Epidemiology, the MMT for most Brazilian cities was around 23 °C—it was lower (21 °C) in Curitiba (Paraná) and higher (around 28 °C) in Palmas (Tocantins) and São Luís (Maranhão).

Days with much lower or higher values than the MMT are considered extreme temperatures. There are not many. They account for 2.5% of the days of the year when temperatures are at their lowest, and 2.5% of the days when temperatures are at their highest. The researchers observed that, for most cities, the graph representing the risk of death at each temperature took the shape of the letter U. This suggests that the probability of death increases as the temperature falls or rises in relation to the MMT. The graph was often in the shape of a U with a slightly drooped left arm, showing that the risk of death increased more rapidly with rising temperatures than with falling temperatures. In Assunção, the capital of Paraguay, for example, where the ideal temperature was around 27 °C, a rise of 5 or 6 degrees doubled the risk of death, whereas this probability increased 50% when the temperature was over 15 degrees below the MMT, despite a greater proportion of people dying from cold than from heat.

The impact of temperature on health varies from one person to another—those who live in hot regions are generally better adapted to the heat and vice versa. It also depends on gender, age, and the existence of chronic diseases, such as asthma and hypothyroidism, as well as time available to adjust to the change. It is greater for small children or the elderly, who have more difficulty regulating their body temperature—as people age, health issues and the use of medications become more frequent, altering how the body functions and potentially aggravating the effects of non-ideal external temperatures.

In another study, published months earlier also in Environmental Epidemiology, Coelho, Saldiva, and colleagues evaluated which age group was most affected by the most extreme hot and cold days—corresponding to those classified among the 1% of the lowest and highest temperatures, respectively—and what the most frequent causes of death were.

The study included data from 532 cities in 33 middle- and high-income countries and corroborated what had been identified in previous smaller studies. Extremely cold days increased the risk of dying by 22%, on average. The probability increased with age, especially for deaths resulting from cardiovascular and respiratory complications. Cardiovascular problems were the leading cause of fatal outcomes on cold days. The cold increased the probability of dying from problems such as heart attack or stroke by 34%, and from respiratory complications by 27%.

Tercio Teixeira / Getty ImagesBeachgoers in Rio de Janeiro during the heatwave in 2023 when temperatures reached 39.9 °CTercio Teixeira / Getty Images

Extremely hot days, in contrast, increased the risk of death by 11%. This probability was more consistent across all age groups and only increased significantly above the age of 75. In the case of heat, however, the greatest contribution was from respiratory issues (asthma, pneumonia, and others) rather than cardiovascular problems. The risk of death from respiratory issues increased by 22%, while the risk from heart and circulatory problems increased by 13%. According to the authors of the study, exposure to very high or very low temperatures can trigger a series of pathophysiological effects, including increases in respiratory and heart rate, changes in blood viscosity and coagulation, blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and inflammatory responses.

“Although lower than that caused by the cold, heat-related mortality has become more significant in recent years,” states Saldiva. And it is likely to worsen in the coming decades if the planet’s average temperature is not contained. In a study published in 2017 in the journal The Lancet Planetary Health, Saldiva and colleagues from the Muti-Country Multi-City consortium calculated the future behavior of deaths from extreme cold and heat in different regions of the planet using data from 451 cities—including 18 Brazilian cities—across 23 countries.

If the worst-case scenarios are confirmed, with temperature increases above 3 °C, the deaths associated with high temperatures will likely rise sharply in different regions of the globe, whereas deaths from the cold should decrease. The most affected regions will be the Central and South Americas, Central and Southern Europe, and Southeast Asia, with deaths from extreme heat increasing by 2.5 to 14 percentage points in the period from 2090–2099 compared to 2010–2019.

In the Central and South Americas, the impact of climate change on increasing the number of hot days is likely to be seen much sooner. Between 2045 and 2054, the number and duration of heat waves is expected to double in most of the region, even in the scenario of the lowest emissions and lowest temperature rise, according to the article published in October in Scientific Reports, by an international group in which Brazilian physician and epidemiologist Nelson Gouveia participated. Gouveia is also from FM-USP but is not part of the studies by Saldiva and Coelho. In the worst-case scenario, the number of heat waves could increase by a factor of 12, with their duration increasing by a factor of 9.

Besides the total number of hot days having increased in recent years—the decade from 2015–2024 concentrates the hottest years since 1850—each degree added to a day of extreme heat increases the risk of death more than the reduction of 1 °C to an already very cold day. In Latin America, the increase in the first case was 5.7%, while the second was 3.4%, stated Gouveia and colleagues in an article published in 2022 in the journal Nature Medicine. “Because of this characteristic, the change in the distribution of temperatures to higher levels, may, at least initially, result in pronounced increases in the risk of death as extreme heat becomes more frequent,” explains Gouveia.

In the study from Nature Medicine, the researchers evaluated the relationship between extreme temperatures and mortality in 326 cities from the region (152 in Brazil). As was confirmed in the study from Environmental Epidemiology, the relationship between temperature and mortality in most cities is represented by a U-shaped curve, with the risk of death increasing more gradually as temperatures decrease. However, above the optimal temperature, the probability of dying rises more steeply with the increase of just a few degrees. The rapid increase in the risk of death from heat was more evident in cities that regularly recorded a daily average temperature of over 25 °C, such as Buenos Aires in Argentina, or Rio de Janeiro in Brazil.

Given this scenario, it is essential that public policies aimed at mitigating and adapting to climate change be adopted and implemented. It is not a new warning, but the measures already put into practice are considered by experts to be slow and insufficient. In addition, the values promised by the international community for the mitigation of climate change during COP20, held in November in Azerbaijan, fell well short of what was desired and should be allocated to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and adaptation plans in poorer countries.

In each city, local factors, such as inadequate local planning, contribute towards increasing the impact of rising temperatures and extreme events (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 346). Years ago, nurse Wolmir Péres, now a retired professor from the University of Pernambuco (UPE), and colleagues compared the effect of extreme temperatures in Florianópolis and Recife. They observed that the proportion of deaths attributed to extreme temperatures was higher in Florianópolis, the capital of the state of Santa Catarina (5.8% for overall mortality) than in Recife, the capital of Pernambuco (1.8%), according to the results published in 2020 in the journal Climate. The urban configuration influenced the effect. “The construction of buildings on the seafront, for example, impedes the circulation of wind, resulting in extreme heat in the central areas. Urban planning needs to consider these repercussions,” suggests Péres.

The story above was published with the title “Fatal temperatures” in issue in issue 348 of february/2025.

Scientific articles

TOBÍAS, A. et al. Mortality burden and economic loss attributable to cold and heat in Central and South America. Environmental Epidemiology. Dec. 2024.

SCOVRONICK, N. et al. Temperature-mortality associations by age and cause: A multi-country multi-city study. Environmental Epidemiology. Oct. 2024.

GASPARRINI, A. et al. Projections of temperature-related excess mortality under climate change scenarios. The Lancet Planetary Health. Dec. 2017.

KEPHART, J. L. et al. City-level impact of extreme temperatures and mortality in Latin America. Nature Medicine. Aug. 2022.

PÉRES, W. E. et al. The association between air temperature and mortality in two Brazilian health regions. Climate. Jan. 19, 2020.

Republish