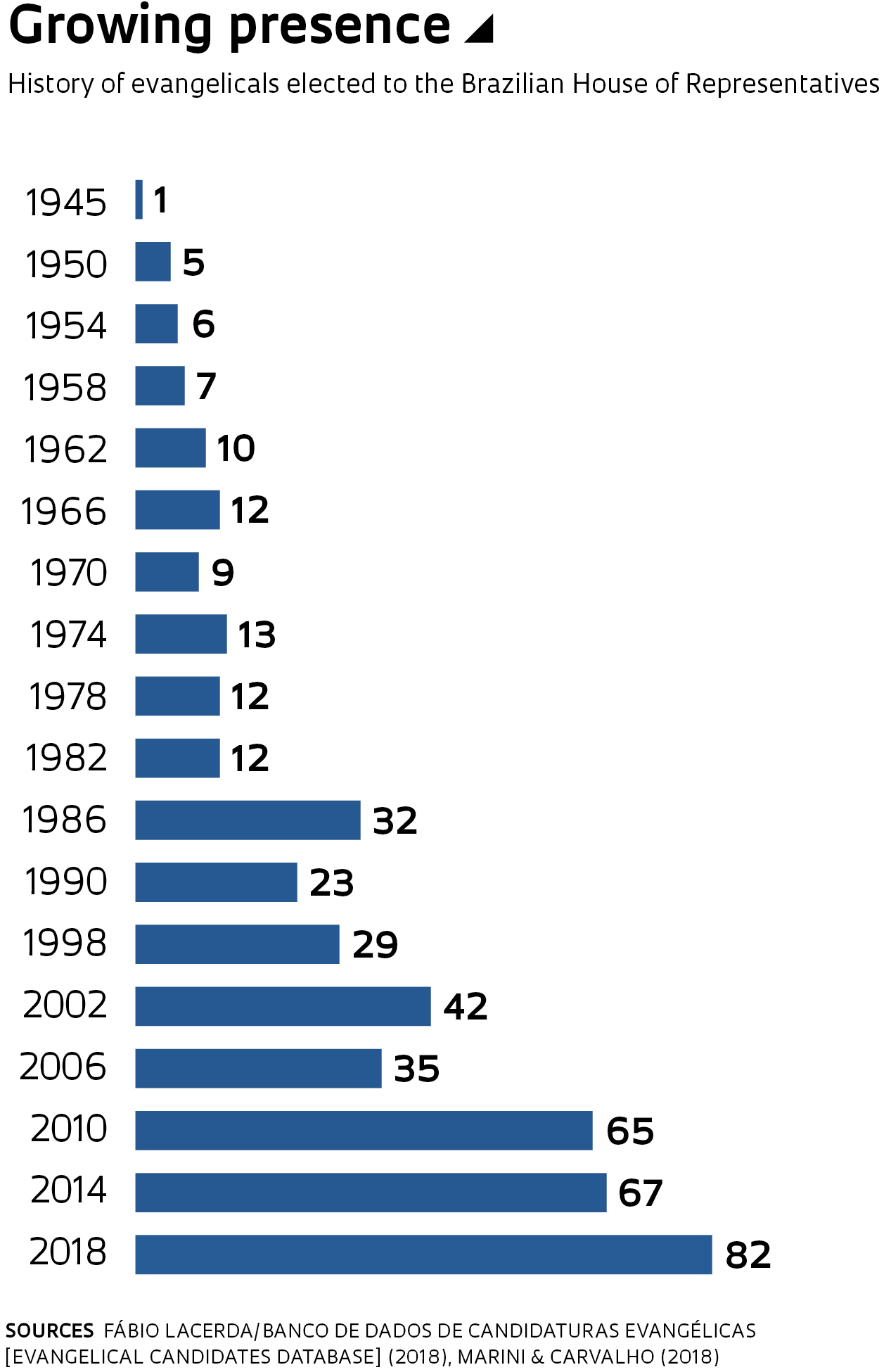

The number of evangelicals participating in Brazilian Congress has increased threefold in the last thirty years. Today they account for 82 congresspeople and nine senators. One of the explanations suggested by experts on government institutions is the “corporate political representation model,” through which large evangelical churches choose candidates from among their pastors to support during the election campaign. “We speak of a ‘corporate model’ when candidates defend the interests of the church to which they are attached, which is different from an evangelical politician who uses their faith as part of their campaign but does not represent or is not directly linked to an organization,” explains political scientist Claudia Cerqueira, who is studying a postdoctorate at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP). Since electoral legislation prohibits campaigns in religious spaces such as temples and churches, the support is usually not explicit. “Religious leaders ask the public to pray for a certain candidate, or leave prayer cards at the entrance to the service,” she explains. Religious programming on public-access television has also contributed to good electoral performance. Some churches, especially the Neopentecostal churches, even have their own radio and television stations, such as the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, which created its own network called Record in 1989. “In general, the official candidates are part of the churches and already have exposure in the media,” he says.

According to Ricardo Mariano, from USP, the Universal Church started putting its leaders forward for election to the legislature in 1986. Most of them are currently linked to the Republicanos party, formerly the Brazilian Republican Party (PRB), which was created in 2003 to replace the Partido Renovista Municipalista party (PMR). Among its founders were politicians associated with the Universal Church and other evangelical bishops, as well as José Alencar, then vice president of Brazil. In July 2019, the party had 415,000 registered voters, according to data from the Superior Electoral Court (TSE). The current vice president of the House of Representatives, Marcos Pereira, and the mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Marcelo Crivella, are two examples of party politicians linked to the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God.

“Sixty percent of evangelicals elected to the National Congress in 2018 are linked to the Universal Church and Assembly of God, showing that political representation from this religious segment owes a lot to just a few large churches,” says political scientist Fábio Lacerda, a researcher at CEBRAP and a professor at the Brazilian Capital Markets Institute (IBMEC) and the Inaciana Educational Foundation (FEI). According to data presented by political scientist Priscilla Leine Cassotta in her PhD thesis, defended in 2019 at the Education and Human Sciences Center of the Federal University of São Carlos (CECH-UFSCar), the percentage of candidates from the Christian Social Party (PSC) who used designations such as pastor, bishop, and brother in their campaigns for congress increased from 3.26% in 1998 to 22.2% in 2018. “The party has a close connection with the Assembly of God, the largest Pentecostal denomination in Latin America,” he says.

Despite having grown in visibility, the participation of evangelicals in politics is not recent, says Mariano, recalling the general elections of 1986, the first after the end of the military dictatorship, as a landmark for the movement. Thirty-two evangelicals were elected to the House of Representatives that year—previously, an average of 10 were voted in at every election. According to the USP sociologist, rumors during the Constituent Assembly that the Catholic Church was trying to influence the drafting of the new Constitution, and that this could jeopardize the religious freedom of evangelicals, had an immediate impact. “A faction was quickly formed in the House, marking the public emergence of evangelical activism at a crucial moment in democracy,” he recalls. “The motto of the evangelicals, which until then had been ‘believers do not get involved in politics,’ became ‘brothers vote for their brothers,'” he explains. “However, unlike the current situation, they were elected without exploiting their religious identity—they earned their position without placing religion at the service of political interests. This only started to happen after the 1989 elections and has become more and more common in recent years.”

Almeida, from UNICAMP, believes that research needs to look beyond congress to understand evangelical influence in other State powers and institutions, such as the Judiciary, the Public Prosecution Office, and the Armed Forces.

A complex landscape

Mariano, from USP, recalls that the evangelical faction formed in the Constituent Assembly, which historically takes a conservative moral position, was already standing against what came to be defined as the criminalization of homophobia, for example. After analyzing 739 bills proposed between 1999 and 2017 by the Christian Social Party (PSC), which today has nine members of congress, six of them evangelicals, Cassotta identified a persistent effort to defend the inclusion of religious education in public and private school curriculums, to tighten the rules of the Child and Adolescent Statute, and to increase the punishment for the crime of contempt against civil and military police officers. “Issues related to family and tradition tend to mobilize and unify evangelical politicians, who end up transferring the moral guidelines of the church into politics,” summarizes Freston, from the Balsillie School of International Affairs.

Despite the conservatism evident in the political agendas, experts call attention to the complexity of the evangelical landscape, which also includes progressives, even if they are the minority. For theologian Helmut Renders of the Methodist University of São Paulo, the conservative discourse became more prominent thanks to the performances of some groups on radio and television. “We must not confuse visibility with representativeness,” says the theologian, highlighting that the National Council of Christian Churches of Brazil—composed of the Brazilian Baptists Alliance, the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church, the Anglican Episcopal Church of Brazil, the Evangelical Church of the Lutheran Confession in Brazil, the United Presbyterian Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch—and other evangelicals not linked to the organization are against reducing gun control, a cause defended by some Pentecostal and Neopentecostal leaders.

One branch that perfectly encapsulates the multiplicity of the evangelical landscape, according to Aramis Luis Silva, a researcher at CEBRAP and UNIFESP in Baixada Santista, is the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC). Founded in the USA in 1968 and present in more than 30 countries, the MCC opened its first church in Brazil 13 years ago and welcomes sexual and gender diversity. Silva mentions other groups, such as Evangelicals for Gender Equality, which also promotes progressive causes.

“The evangelical movement in Brazil is not homogeneous,” reinforces anthropologist Jacqueline Moraes Teixeira, from the Department of the Philosophy of Education and Educational Sciences at USP’s School of Education, who researches the Universal Church’s projects involving gender and sexuality. She points out that the Church proposes to support women in situations of violence, providing lawyers and social workers to help victims, who do not necessarily need to be evangelical. “On the one hand, there is an acknowledgment of violence, of the need to bring justice and sometimes consider divorce, but on the other, the Universal Church distances itself from feminist agendas and discussions on gender violence seem to be treated as fundamental to the construction of the heterosexual family,” explains the researcher. According to the 2010 census, more than half of those who attend evangelical churches are women.

Republish