On cold nights in the 1950s in Teresópolis, Rio de Janeiro, engineer and physicist Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro (1906–1960), together with his nine children, would wrap themselves in blankets on the lawn of the family’s vacation home to gaze at the starry sky. “The sky, which he described poetically, was a marvelous infinity,” recalls anthropologist Yvonne Maggie de Leers Costa Ribeiro, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), as she remembers how her father pointed out constellations and explained the origins of their names (see Pesquisa FAPESP, issue nº 295).

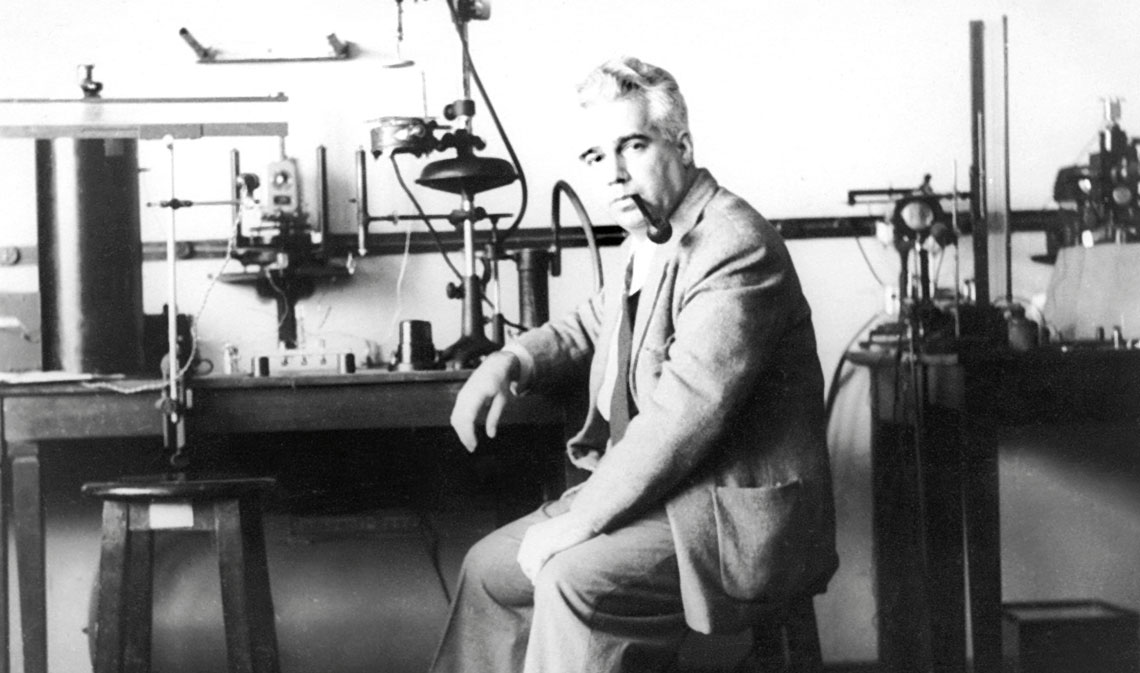

COSTA RIBEIRO, J. Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. 1945 Apparatus developed by Costa Ribeiro and Luigi Sobrero to precisely measure angles of light reflectionCOSTA RIBEIRO, J. Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. 1945

Through letters, photographs, and film footage, the documentary Termodielétrico (Thermodielectric)—released in October 2024 and directed and narrated by filmmaker Ana Costa Ribeiro, one of his granddaughters—follows the personal and scientific journey of her grandfather, the discoverer of the phenomenon known as the thermodielectric effect. Defined as the ability of certain materials to generate an electric current when transitioning between physical states—from solid to liquid or vice versa—this property was first identified in carnauba wax. As a result of this transformation, materials with a permanent electric charge, known as electrets, were produced and are now used in components of electronic devices.

Although not as widely recognized as his contemporaries, such as César Lattes (1924–2005) and Mário Schenberg (1914–1990) (see Pesquisa FAPESP, issues 307 and 340), Costa Ribeiro made important contributions to the advancement of research and the development of Brazilian science. A pioneer in what is now known as condensed matter physics, which focuses on the study of the properties of matter and its fundamental elements, such as atoms and electrons, he was a founding member of the Brazilian Center for Physics Research (CBPF) in 1949 and of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) in 1951, where he served as the first scientific director.

Costa Ribeiro’s maternal lineage came from mill owners in Pernambuco. His father, originally from Paraíba, was a third-generation law graduate—his grandfather, from whom he inherited his name, was a judge. In 1924, Costa Ribeiro began studying civil engineering at the Polytechnic School of the University of Rio de Janeiro, which was renamed the University of Brazil in 1937 and later became the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) in 1965. In 1929, shortly after completing his degree, he was hired as an assistant professor of experimental physics at the Polytechnic School.

In 1934, Costa Ribeiro married Jacqueline de Leers (1911–1957), a Frenchwoman who had immigrated to Brazil in 1917. To support his growing family, he taught not only at the Polytechnic School but also at a secondary school and at a technical school affiliated with the University of the Federal District (UDF), which was dissolved in 1939 and absorbed into the University of Brazil.

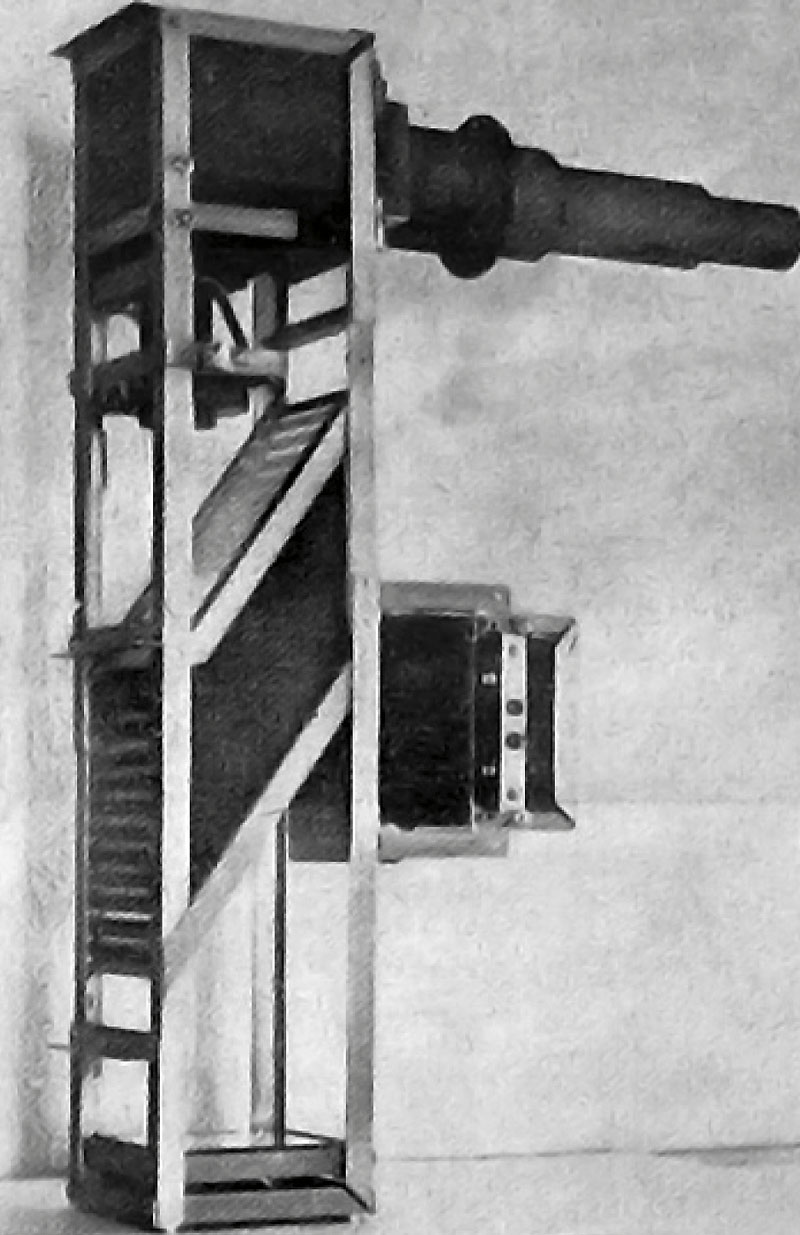

Costa Ribeiro Collection – Mast / Silva Filho, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013A diagram of the experiment used to verify the thermodielectric effectCosta Ribeiro Collection – Mast / Silva Filho, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013

At the beginning of his scientific career, he measured the radioactivity of minerals such as uraninite (also known as pitchblende)—the mineral in which the Franco-Polish physicist and chemist Marie Curie (1867–1934) first identified radium, a radioactive element. Costa Ribeiro placed samples in an ionization chamber and measured the electrical voltage, from which he derived the ionization current, an indicator of the mineral’s level of radioactivity.

According to physicist and historian of science Wanderley Vitorino da Silva Filho, from the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), in the book Costa Ribeiro: Ensino, pesquisa e desenvolvimento da física no Brasil (Costa Ribeiro: Teaching, research, and the development of physics in Brazil; Livraria da Física, 2013), Costa Ribeiro adapted the original method to achieve faster and more accurate measurements. He confirmed that uraninite contained high levels of both radium and another radioactive element, uranium, publishing his results in the Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências in June and December 1940.

Leopoldo Nachbin Collection – MAST / SILVA FILHO, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013In front of the National School of Philosophy of the former University of Rio de Janeiro, in the early 1940s. From left to right: Alcântara Gomes, Elisa Frota-Pessoa, Jayme Tiomno, Costa Ribeiro, Sobrero, Leopoldo Nachbin, José Leite Lopes, and Maurício PeixotoLeopoldo Nachbin Collection – MAST / SILVA FILHO, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013

In the late 1930s, at UDF and the National Institute of Technology, German physicist Bernhard Gross (1905–2002) was searching for alternatives to rubber for coating telephone cables, which were prone to rapid deterioration. Insulating materials such as rubber, glass, ceramics, and plastic are referred to as dielectrics if, when subjected to voltages beyond their breakdown limits, they become conductive. Gross was investigating anomalies in dielectric behavior, particularly in capacitors (then called condensers), where materials would regenerate an electric charge even after it had been dissipated by a short circuit.

Another change involved the formation of electrets, materials that retain a permanent electric charge. A notable example was carnauba wax, derived from the powder of a palm tree native to northeastern Brazil. In the 1920s, Japanese physicists had produced electrets by applying an electric charge to carnauba wax during its solidification. Gross sought to determine whether temperature changes played a role in electret formation, experimenting with the wax inside electrically charged and heated capacitors. Decades later, in the 1960s and 1970s, he made key contributions to the development of the electret microphone, one of the two main types of microphones used in cell phones today.

In 1943, Costa Ribeiro began to study the potential influence of radioactivity on this phenomenon. To his surprise, samples of carnauba wax mixed with radioactive elements developed an electric charge comparable to that of pure samples. He realized that no external electric field was needed to produce an electret. “He melted the wax, let it solidify, and saw that it became strongly electrically charged,” explains Silva Filho. Intrigued by the origin of the charge, Costa Ribeiro decided to measure the voltage of the wax during the solidification process and detected an electric current. “Then he did the reverse: he melted the wax and, during melting, measured the electric current again. It appeared once more,” Silva Filho adds. Costa Ribeiro repeated the experiments with other dielectric materials, including paraffin and naphthalene (both petroleum derivatives), as well as resin extracted from pine trees. In each case, he observed the emergence of electric current during the change of physical state.

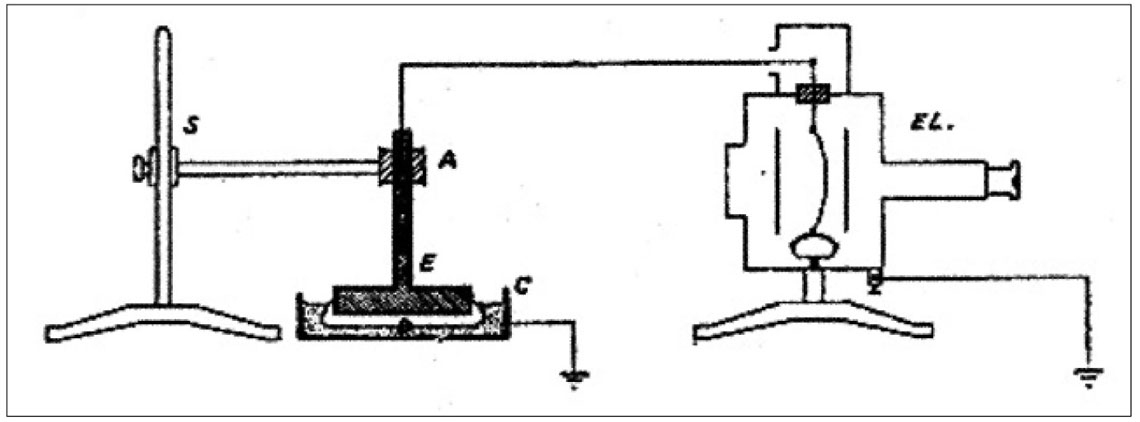

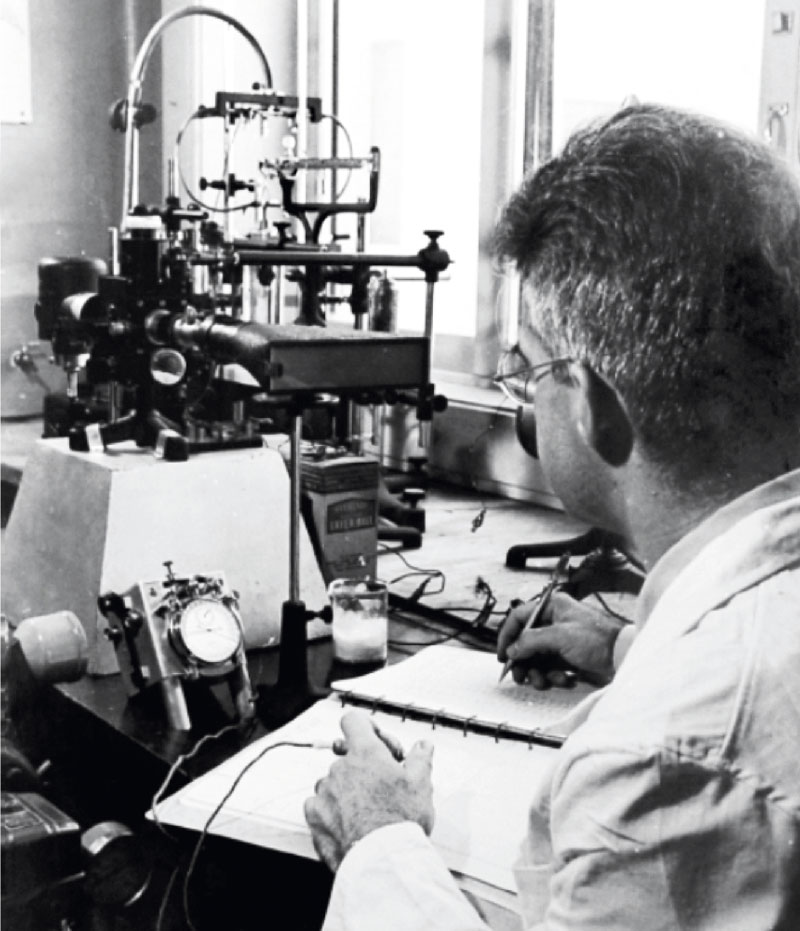

Costa Ribeiro Collection – MAST / SILVA FILHO, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013Costa Ribeiro observing the properties of dielectric materialsCosta Ribeiro Collection – MAST / SILVA FILHO, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013

“Sérgio [Mascarenhas, 1928–2021] and I helped Costa Ribeiro with the measurements, without any grant or pay,” recalls physicist Yvonne Mascarenhas, a retired professor from the São Carlos Institute of Physics at the University of São Paulo (IFSC-USP) and the first wife of Sérgio, also a physicist (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 258 and 305). “Every measurement required someone to observe the scale and take notes. Two or three people had to participate in an experiment. I learned a great deal just by talking with him—he was always very attentive.”

The experiments revealed fundamental physical relationships in dielectric materials. The intensity of the electric current was found to be proportional to the rate of the phase change: the faster the transition, the greater the electric charge generated. It was also proportional to the amount of material undergoing the change. Moreover, the phenomenon was shown to be reversible: the charge generated during melting had the same intensity as that generated during solidification. Due to this intrinsic relationship between heat and electric charge in dielectric materials, Costa Ribeiro named the phenomenon thermodielectric. He presented his findings to the Brazilian Academy of Sciences (ABC) in 1944. The complete results were later compiled in his thesis, Sobre o fenômeno termodielétrico (On the thermodielectric phenomenon), which he defended in 1945 to assume the Chair of Physics at the then University of Brazil.

Proud of the first physical phenomenon to be entirely discovered and described by a Brazilian in Brazil, members of the ABC began referring to it as the “Costa Ribeiro effect,” a name that gained traction nationally. Although Costa Ribeiro presented his findings in Paris, at Sorbonne University, and attracted the interest of oil company Shell, he chose to publish primarily in Brazilian scientific journals. This may be partly due to a controversy that arose in May 1950, when two American physicists, Everly Workman (1899–1982) and Stephen Reynolds (1916–1990), from the New Mexico School of Mines, in the United States, published an article in Physical Review describing the appearance of electric charges during the freezing of impure water—an effect they believed could explain atmospheric electricity. Despite protests from Brazilian scientists, the phenomenon came to be known in the United States as the Workman-Reynolds effect. In the 1950s, there was a US proposal to rename it the Workman-Reynolds-Ribeiro effect, but the name did not gain widespread acceptance. Outside the United States, the phenomenon is most commonly referred to as the thermodielectric effect, in accordance with the name Costa Ribeiro himself had proposed.

CLEARQ-UNICAMP, Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro ArchiveSome founding members of the CNPq, from the left: César Lattes, Costa Ribeiro, Mário Abrantes da Silva Pinto, and Mário SaraivaCLEARQ-UNICAMP, Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro Archive

With his academic reputation firmly established, Costa Ribeiro became an advocate for public policies to support scientific research. In the late 1940s, alongside Lattes and other prominent scientists, he helped lead the movement to create a national research funding agency. “For two years, they pressured the government to establish the CNPq, and they succeeded,” says physicist Sergio Machado Rezende, of the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), who served as Brazil’s Minister of Science and Technology from 2005 to 2010.

Throughout the 1950s, Costa Ribeiro was a member of the National Nuclear Energy Commission (CNEN) and represented Brazil in international discussions on the peaceful use and control of atomic energy. He participated in debates at the United Nations (UN) in Paris and Geneva, and in 1955, in Washington, DC, contributed to drafting the statute of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), created to oversee the application of nuclear energy. He later served at the agency’s headquarters in Vienna in 1959. Footage from some of these international missions appears in the documentary Termodielétrico.

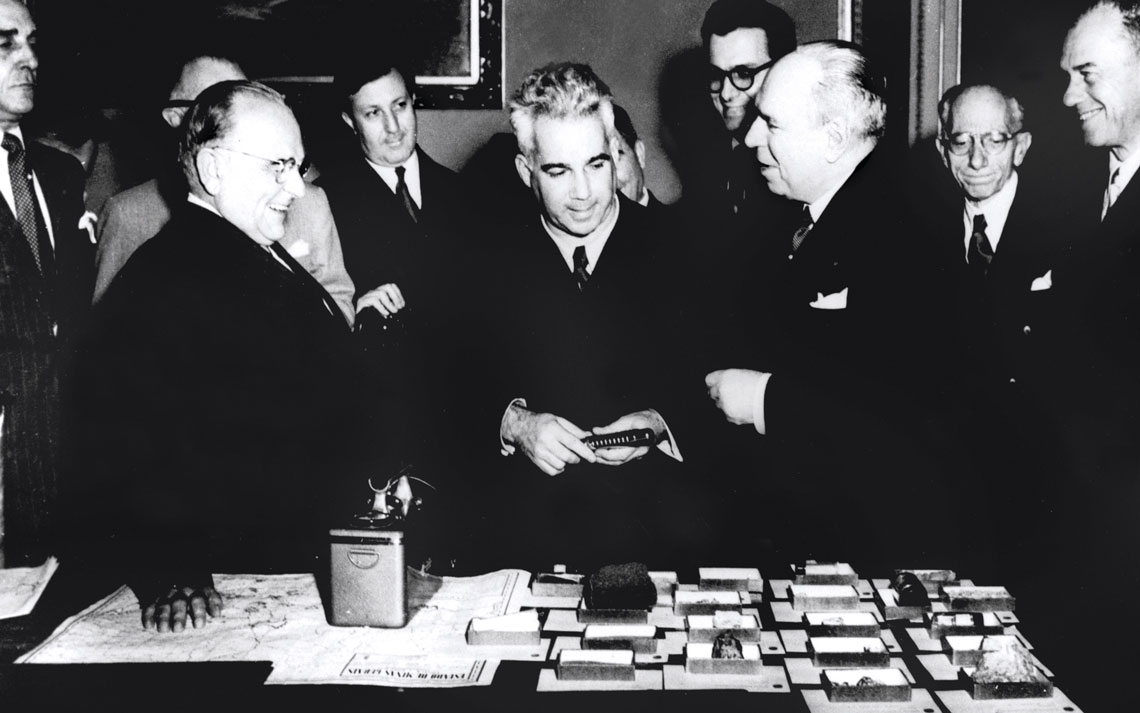

CLEARQ-UNICAMP, Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro ArchiveGetúlio Vargas welcomes Almirante Álvaro Alberto, Director of the CNPq (to the right), and Costa Ribeiro, Scientific Director, in 1953CLEARQ-UNICAMP, Joaquim da Costa Ribeiro Archive

Ana Costa Ribeiro, director of the documentary, never knew her grandfather personally. She began researching his life while mourning the death of her father, chemist Carlos Costa Ribeiro (1939–2015). In the film, she recounts the moment she discovered a collection of her grandfather’s work at the Museum of Astronomy and Related Sciences (MAST): “What I found there was much more than scientific research. I found an endless curiosity, someone who wonders about everything around us, who observes without hierarchy.”

In an interview with Pesquisa FAPESP, she shared a charming family anecdote: to help serve their large family, one of her uncles, physicist Paulo da Costa Ribeiro (1940–2023), invented a miniature train that circled the table, carrying platters of food.

Costa Ribeiro Collection - MAST / SILVA FILHO, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013As a representative of Brazil, at a United Nations conference in December 1954 in MontevideoCosta Ribeiro Collection - MAST / SILVA FILHO, W. V. Costa Ribeiro. 2013

Costa Ribeiro nurtured his children’s curiosity and sense of wonder with simple experiments. “In the dark room, he would open a crack in the shutter and let in a strip of light, which would fall on a diamond and illuminate the whole room like a myriad of rainbows,” recalls his daughter, anthropologist Yvonne Maggie. Although she didn’t retain the scientific explanations, she remembers something perhaps more profound: “What stuck is the mystery, the question.” Nearly all of Costa Ribeiro’s children learned to read at home, taught by their mother, and developed a passion for research.

Costa Ribeiro’s legacy has continued through generations. One of his former students, Sérgio Mascarenhas, established a condensed matter physics research center, the IFSC-USP, grounded in studies of the thermodielectric effect. In turn, Mascarenhas’s student, Sérgio Rezende, went on to create another research hub in the same field at the Federal University of Pernambuco, in Recife.

The story above was published with the title “Sources of electricity” in issue in issue 350 of april/2025.

Scientific articles

LEAL FERREIRA, G. F. Há 50 anos: O efeito Costa Ribeiro. Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física. Vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 434–43. Sept. 2000.

WORKMAN, E. J. & REYNOLDS, S. E. Electrical phenomena occurring during the freezing of dilute aqueous solutions and their possible relationship to thunderstorm electricity. Physical Review. Vol. 78, no. 254, pp. 254–59. May 1, 1950.

Book

SILVA FILHO, W. V. Costa Ribeiro: Ensino, pesquisa e desenvolvimento da física no Brasil. Campina Grande: EDUEPB. São Paulo: Livraria da Física, 2013 pp. 266–69.