In 2014, Danish multinational Maersk, a global giant in the container shipping industry, discovered that the shipment of a single refrigerated container from Africa to Europe involves as many as 30 people and organizations, totaling more than 200 different interactions between each end of the transaction. The company calculated that the costs associated with document processing and management represent a fifth of the entire shipment value. To simplify the process, reduce expenses, and shorten delivery times, Maersk turned to a new technology known as blockchain.

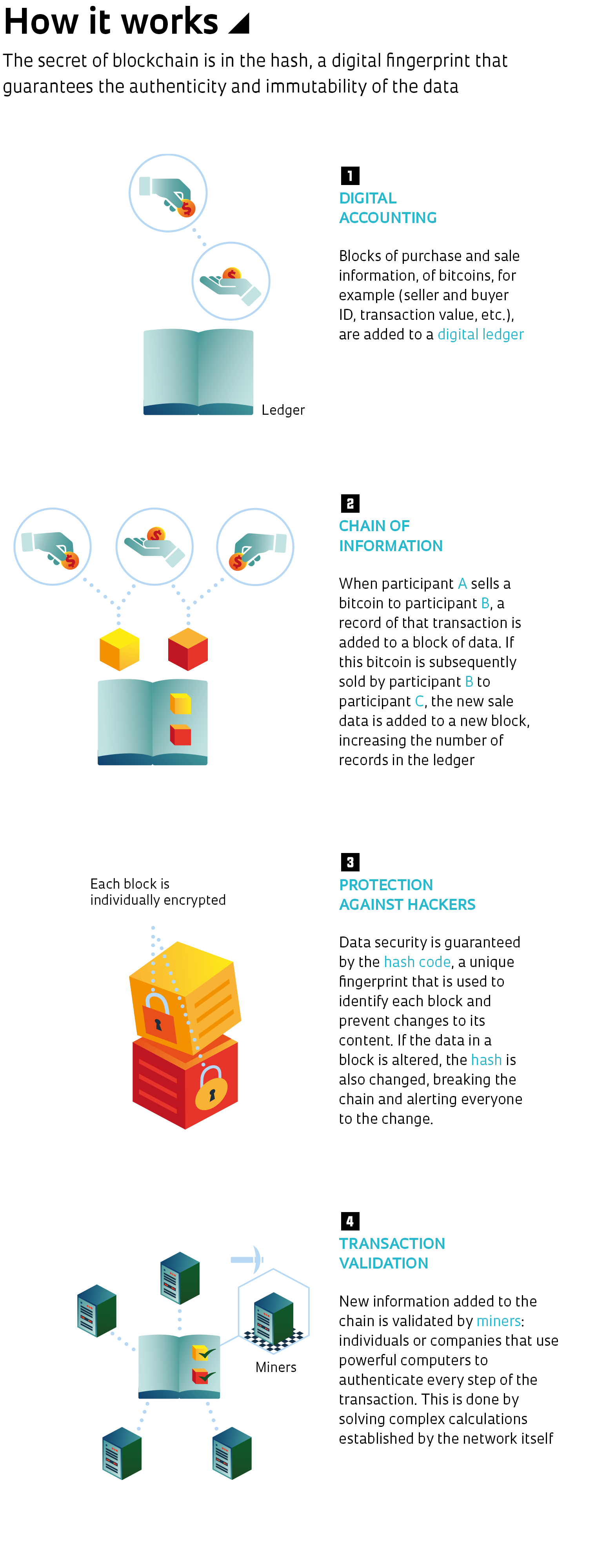

A blockchain functions as a decentralized digital ledger, with the data stored by everyone involved in the transaction. Protected by cryptography, the information stored in the system is, in theory, immutable and fraud-proof. The security of the network is also ensured by the fact that rather than the data being stored centrally on a single server, it is distributed across a network of independent computers, making it more difficult for hackers to alter records. Information about each transaction is added to the end of the digital ledger, forming a sequential chain of blocks, each of which contains the data from the previous block as well as the new data. Data transparency, security, and immutability are the central features of the system.

The technology emerged in 2008 to support the commercialization of bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency. Surrounded by mystery, its origin is credited to Satoshi Nakamoto, the same person who created bitcoin, but nobody knows for sure who Nakamoto is or where he or she is from. There are some who believe that it is not even an individual, but a group of programmers.

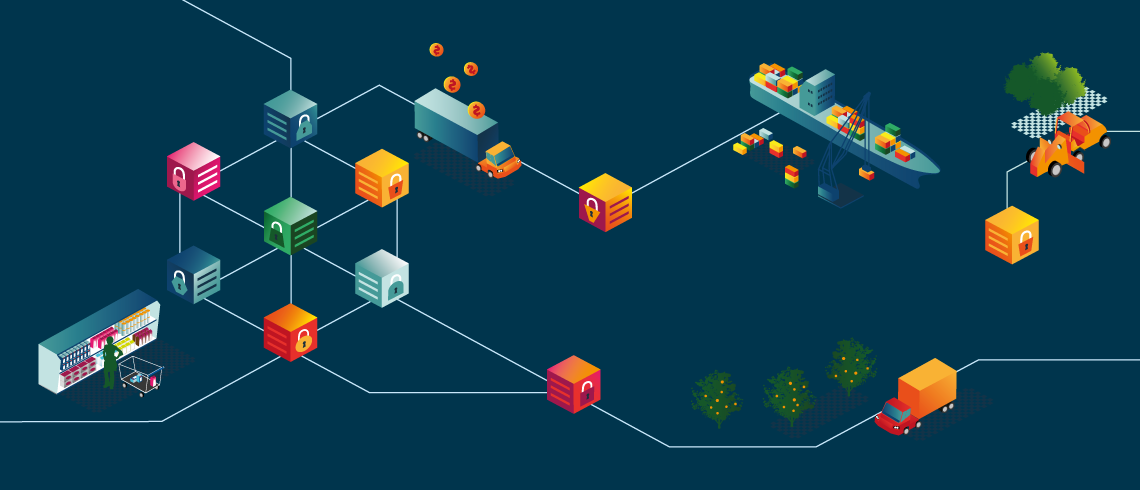

In recent years, the use of blockchain has exploded, and today it is used in banking records, corporate document management, food-chain tracking, and shipping, by companies like Maersk. In partnership with IBM, the Danish multinational has just launched a digital platform based on the technology called Tradelens, which already has dozens of users, including shipping firms, ports, and customs authorities.

“The blockchain sequences events in a totally decentralized system, involving people who do not know or trust each other, where we have to know the order in which these events occurred,” says data security expert Marcos Antônio Simplício Júnior, a professor at the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo (POLI-USP). “With financial transactions, blockchain can be used when there is no entity within the system that is responsible for ordering events, like a bank does for transactions involving its account holders.”

Bitcoin is the most famous example, with the currency being bought and sold with no bank intermediating or controlling the transactions. The system is controlled by the participants themselves. The security of the transactions is based on the hash, a unique code like a digital fingerprint that identifies each block in the chain and guarantees the immutability of the data. If the data in a block is changed, the hash also changes, affecting the link to the previous block and thus breaking the chain.

But if nobody in the network knows each other, who verifies whether a new block to be added to the ledger is correct? This question was solved by creating what are known as miners: users (often companies) with significant computing power are responsible for performing complex calculations to validate the blocks to be added to the chain. Records of all transactions are stored on the miners’ computers, which function as auditors of the process. “Anyone capable of processing high levels of data can join a blockchain network as a miner. In the case of bitcoin, miners are paid for their efforts in cryptocurrency,” says Marcos Simplício.

He explains that as well as public blockchain networks with no central controller that anyone can join, such as those used by cryptocurrencies, there are also private blockchain networks created by companies making use of the technology—like the one created by IBM and Maersk. “What differentiates one from the other,” says the USP professor, “is that private networks must have a central authorizing entity—usually the organization that created it—which is responsible for defining who can join the network.” This entity is often also tasked with validating the information added to the blockchain, either replacing or supplementing the miners.

One of the companies investing most heavily in this technology is IBM, which specializes in creating private blockchain systems for a range of applications. There are also a number of open-source options, such as MultiChain and HyperLedger, that can be used by anyone who wants to create a blockchain for their business. “We track more than 300 products and have recorded more than 3 million blockchain transactions in the food supply chains of multiple countries,” says computer scientist Percival Lucena, responsible for blockchain projects at the IBM Research Laboratory in São Paulo.

The Walmart supermarket chain is one of IBM’s partners. It uses the Food Trust blockchain for its supply chain in the USA. If a product is identified as contaminated, it is possible to know exactly what region it came from, where it has been, and where it is being sold. When it first tested the technology, Walmart reduced the time needed to track a product from seven days to about two seconds.

Software is available that can be used to create private blockchain networks

In Brazil, IBM Food Trust has been piloted by food manufacturer BRF and Carrefour to inform consumers of the origin of their food. The system was tested in 2017, when supermarkets received a batch of frozen pork cuts from BRF with a QR code (two-dimensional barcode) on the packaging. The code provided detailed information about the product, such as the manufacturer name, production date, and transport data from the source to the point of sale. The project evolved and a new version of Food Trust is now being tested in the country. IBM has also developed a solution called AgTrace, a blockchain for agricultural exporters that is being tested by producers of organic food and coffee in Brazil.

São Paulo–based startup Compplied Computação Aplicada is also investing in blockchain applications for use in agriculture. One of its solutions, called Corrente, is designed to make financial transactions in the sector more traceable. “Our focus was on optimizing existing processes by adopting a blockchain model to validate transactions and reduce uncertainties,” said computer scientist David Kwast, the lead researcher on the project at Compplied.

Documents such as invoices, shipping forms, phytosanitary certificates, and quality reports are already part of the supply chain, but with the blockchain, they are transformed into immutable digital data, visible to everyone involved. According to software engineer José Ricardo de Oliveira Damico, one of the founders of Compplied, using blockchain technology could make it easier to successfully apply for credit and insurance. “Blockchain facilitates the business side of agriculture, since buyers want to know with certainty that the producer will be able to provide a harvest under contracted conditions,” says the engineer.

Supported by the FAPESP Technological Innovation in Small Businesses (PIPE) program, the company created a feature that allows network participants to operate offline, which theoretically should not be possible in a blockchain because transactions have to be added in real time, in the sequence they occur. This feature is important because rural producers are not always able to connect to the internet immediately. Still in progress, Compplied expects to complete the project later this year.

Although blockchain technology is gaining popularity, there are some challenges yet to be overcome. “The high energy costs of the process are a concern,” says computer engineer Lucas Lago, from the Center for Society and Technology Studies at USP (CEST-USP). The Digiconomist website has created its own methodology for estimating the energy consumption of blockchain miners worldwide. In March, it calculated that the bitcoin network uses at least 44 terawatt hours (TWh) per year, the same energy consumption as the entire country of Peru. According to Lago, there are several ways of tackling the problem, including potential changes to the blockchain algorithm, but this is an issue that still needs to be addressed. Another more local problem, according to the expert, is the lack of people being trained to work with technology.

Léo Ramos Chaves

A coffee farm in the state of São Paulo: blockchain could help agricultural businesses

Léo Ramos Chaves Right to be forgotten

Marcos Simplício, a professor at POLI-USP, says that blockchain can often be a solution to a problem that does not exist. “Nine out of every 10 touted blockchain applications make little sense,” he says. According to Simplício, many private blockchain networks are unnecessary because there is already a level of trust between the participants, who know each other personally. “In these cases, digital signatures for each transaction or a distributed file system would be enough, eliminating the need for the costly mining process,” he says.

He also points out that in private networks, the validation of blocks often falls to one or a group of companies, corrupting the original spirit of the blockchain, which is the absence of a central institution. Furthermore, the technology does not necessarily dispense with the need for human supervision. “You cannot be sure that a box actually contains the product, unless some trusted entity opens it, looks inside, and records the result in the blockchain, creating a digital record of the product’s validity,” says the POLI-USP professor.

Another issue concerning developers and users is new data protection laws, such as the EU’s General Data Privacy Regulation (GDPR) and Brazil’s General Data Protection Law, which among other measures, establish the right to be forgotten—whereby everyone has the right not to have facts about their private life exposed to the public on the internet or through any other media. It is not known how this can be put into practice with blockchain, since any information contained in the system cannot be changed or removed.

Trading cryptocurrencies Buying and selling these digital assets is unregulated and high riskUnlike conventional notes and coins, cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin, litecoin, and binance coin do not physically exist—they are purely digital files. These financial assets are similar to shares traded on stock exchanges, with a key difference: cryptocurrency transactions involve no regulatory institution, such as the Central Bank of Brazil, and are traded directly by those buying or selling the currency.

To operate in this market, traders have to create a virtual wallet, which usually requires an account with a cryptocurrency exchange. All transactions are then conducted between traders based on a blockchain platform that validates and records the financial activity.

Since its launch, the value of bitcoin, the world’s best-known cryptocurrency, has swung wildly, and in March 2019 it was worth around R$16,000—at its peak in December 2017, it was worth R$64,000. The price of a cryptocurrency fluctuates based on supply and demand, just like shares on a stock market. Because the sector is unregulated, transactions are considered to be high risk.

Project

Development of a blockchain system for tracking and intermediating in agricultural operations and transactions (nº 17/01037-6); Grant Mechanism Technological Innovation in Small Businesses (PIPE); Principal Investigator José Ricardo de Oliveira Damico (Compplied); Investment R$81,981.91.

Republish