After Pluto was stripped of its planetary status in August 2006 by the International Astronomical Union (IAU)—on the grounds that it was too similar to newly discovered objects beyond Neptune’s orbit—the hypothesis that additional worlds might still exist in the outer reaches of the Solar System was revived with renewed interest. However, over the following decade, these searches yielded little of significance or excitement.

That changed in 2016, when two astronomers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Mike Brown and Konstantin Batygin, published a paper in The Astronomical Journal formalizing an idea originally proposed two years earlier by Chadwick Trujillo of Northern Arizona University and Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science: that far beyond the Kuiper Belt, at the edge of the Solar System, there may exist an as-yet-undiscovered giant planet. The Kuiper Belt is a ring-shaped region beginning just beyond Neptune, the most distant known planet from the Sun. It is composed of millions of icy bodies of varying sizes, including one of the largest, Pluto itself.

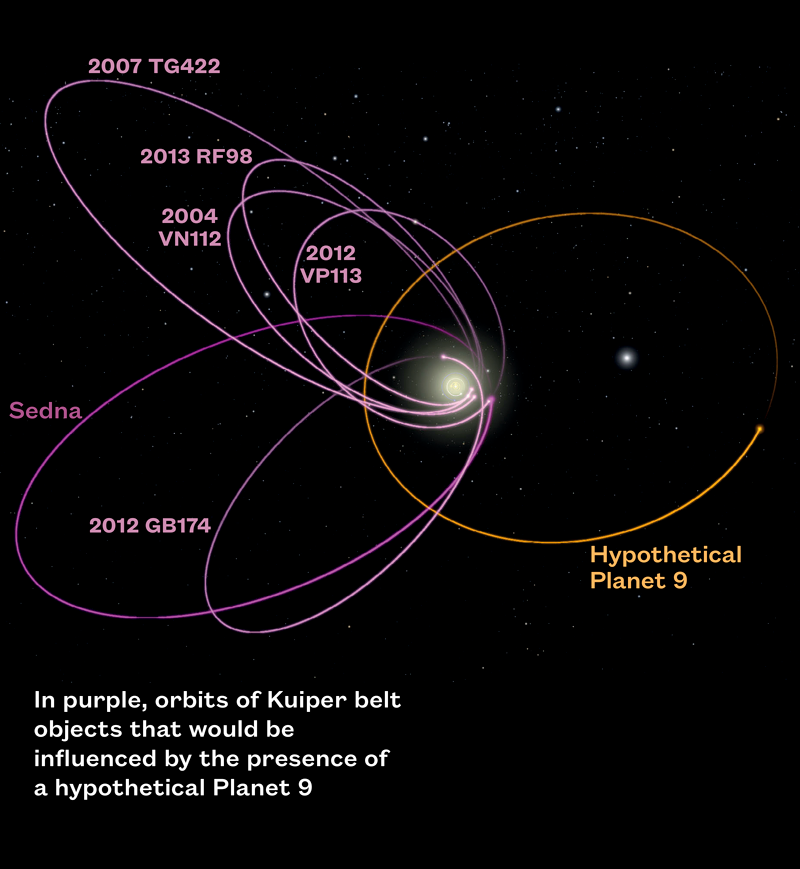

To date, there is no direct observational evidence for the existence of this hypothetical planet, dubbed Planet 9 by Brown and Batygin. Nonetheless, according to defenders of the hypothesis, its proposed presence offers the most compelling explanation for the unusual orbital patterns of about a dozen Kuiper Belt objects identified over the past two decades, including the dwarf planet Sedna and several others known only by alphanumeric designations. These bodies follow highly elongated, elliptical orbits that consistently point toward the same region of the sky. This unusual behavior could be attributed to gravitational interactions with the massive, unseen Planet 9 (see image).

A study led by Brazilian astrophysicists and published in February of this year in the online edition of the scientific journal Icarus refines this hypothesis, calculating the mass and probable location of Planet 9 that would best account for the current configuration of the Solar System, including the anomalous orbits of objects in the Kuiper Belt.

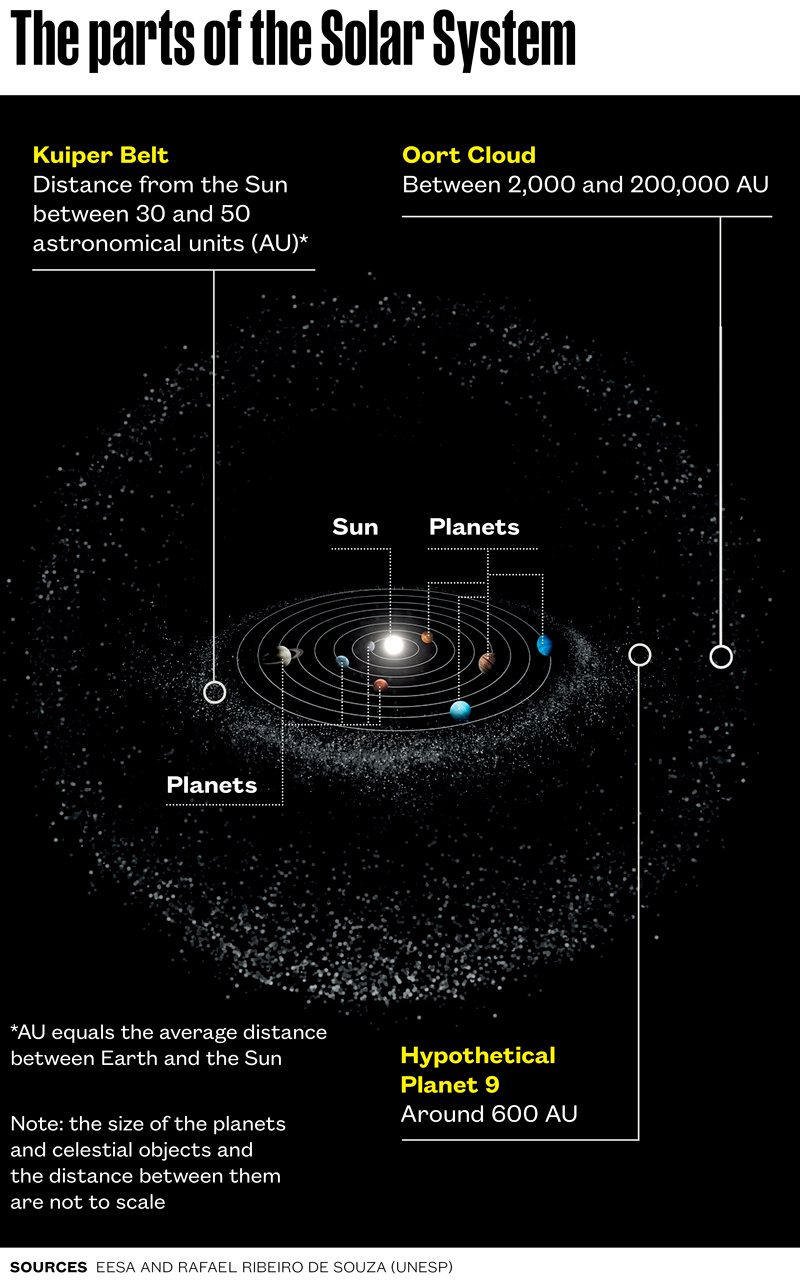

According to the study, which used computer simulations to model the formation of the Solar System’s outermost region 4.5 billion years ago and its subsequent evolution, Planet 9 would have a mass approximately 7.5 times that of Earth and would be located at a distance of about 600 astronomical units (AU). In other words, it would lie 600 times farther from the Sun than Earth does—one AU being the average distance between Earth and the Sun, roughly 150 million kilometers. For comparison, Neptune orbits at around 30 AU from the Sun.

“With these parameters, Planet 9 leads, in our simulations, to the formation of the four gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune), the Kuiper Belt, and the entire outer region of the Solar System with characteristics closely matching what we observe today. It was a perfect match,” says astrophysicist Rafael Ribeiro of São Paulo State University (UNESP), Guaratinguetá campus, and lead author of the study. “Previous studies by other research groups had suggested that Planet 9 should have a mass between 10 and 15 times that of Earth.”

One of the major contributions of the study is its ability to reproduce, in simulations, the formation of a very rare class of Solar System objects: small ecliptic comets. These bodies follow orbits in the same plane as Earth’s and their orbital period (the time it takes to go around the Sun) is quite short, around 20 years. To date, only four such comets with diameters greater than 10 kilometers are known.

In the computer model, when Planet 9 was incorporated into the scenario of Solar System formation, the number of such distinctive comets generated ranged from 1.8 to 3.6—comparable to the four observed ecliptic comets. “The study shows that the most refined and up-to-date parameters we propose for Planet 9 are broadly consistent with the existence of this population of comets,” says Brazilian astrophysicist André Izidoro of Rice University in the United States, a coauthor of the study.

In the article, the researchers also estimate the eccentricity of Planet 9’s probable orbit—that is, how elongated its path around the Sun might be—as well as its orbital inclination, which would be approximately 20 degrees relative to the plane in which the other planets orbit. In the Solar System, the known planets revolve around the Sun with inclinations close to zero degrees.

“Basically, what we do in the simulations is introduce the hypothetical Planet 9 into the formation process of the Solar System and observe the results,” explains physicist Othon Winter, coordinator of the Orbital Dynamics and Planetology Group at UNESP and a coauthor of the paper. “By adjusting the mass and distance, we test whether any configuration of Planet 9 is compatible with the formation of a system like ours.” This approach does not prove the existence of a new planet; rather, it suggests that Planet 9, if it exists with a certain mass and orbital location, is not incompatible with the structure of the Solar System as we know it.

Should such a planet exist in the position indicated by the study, confirming its presence in the distant reaches of the Solar System would be an enormous observational challenge. A celestial body located at 600 astronomical units (AU) would lie far beyond the Kuiper Belt, whose objects range roughly from 30 to 50 AU from the Sun. At present, no telescope or observation instrument is capable of clearly detecting objects that far beyond the Belt, a structure that is twenty times closer to Earth than the region where Planet 9 is theorized to reside. Strictly speaking, according to the Brazilian researchers’ calculations, this hypothetical planet would be “lost in interstellar space,” situated between the outer edge of the Kuiper Belt and the inner boundary of the proposed Oort Cloud.

Unlike the Kuiper Belt, which has been conclusively observed and is relatively compact, the Oort Cloud remains a theoretical construct, though it is widely accepted within the astrophysics community. It is described as a vast, spherical shell or bubble that would envelop the entire Solar System. Like the Kuiper Belt, it would consist of icy, rocky bodies of various sizes—remnants from the early formation of the Solar System. The inner edge of the Oort Cloud is believed to begin around 2,000 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, nearly 3.5 times farther than the location predicted for Planet 9 in the new study. Long-period comets, which take more than 200 years to complete an orbit around the Sun, are thought to originate from the Oort Cloud.

The Vera Rubin Observatory, currently in the final stages of construction in Chile and scheduled to begin operations in 2025, is expected to play a key role in either confirming or refuting the existence of Planet 9 within its first one to two years of operation. Funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the US Department of Energy (DOE), the telescope will feature an 8.4-meter primary mirror and the largest astronomical camera ever built, with a resolution of 3,200 megapixels. One of its primary missions is to conduct a detailed survey of the Solar System, including the vast region beyond Neptune where the hypothetical new planet may be located. “With a bit of luck, it’s possible that Vera Rubin will be able to observe the planet where we think it might be,” says Winter.

Even if the observatory does not succeed in capturing direct images of a new planet in the outer Solar System, its observations could help address or reinforce the main criticism directed at proponents of the Planet 9 hypothesis. Skeptics argue that the available indirect evidence for such a planet existing beyond Neptune’s orbit is not sufficiently robust. They contend that the apparent clustering of certain Kuiper Belt objects—whose highly elongated orbits seem to point toward the same region of the sky—may be an illusion caused by observational bias. Objects that happen to be near the Sun in their orbits and lie along the plane of the known planets are far easier to detect than those in less favorable positions.

“Our data on the most extreme objects [located beyond Neptune] are entirely consistent with a random distribution,” astrophysicist Samantha Lawler of the University of Regina in Canada—who specializes in the study of Kuiper Belt objects—told Astronomy magazine last year. “I really don’t think there is any clustering.”

Nevertheless, there is broad consensus that the commissioning of the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile will mark a significant step forward in the search for new planets within the Solar System. “Vera Rubin may not discover the planet directly, but it will help us determine whether the unusual orbits of some distant Kuiper Belt objects are real or merely the result of observational bias,” says Italian astrophysicist Alessandro Morbidelli of the Côte d’Azur Observatory in Nice, France, in an email interview with Pesquisa FAPESP. “It will conduct an exhaustive mapping of this region. If these orbits are real, the planet will be there.” A leading expert in the dynamics of Solar System formation, Morbidelli coauthored the Icarus article alongside his Brazilian colleagues.

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute For 76 years, Pluto was considered a planet, until it was demoted to the category of dwarf planetNASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute

The Fall of Pluto In the Solar System, any celestial body that is not a natural satellite, such as the Moon, can only be classified as a planet if it meets three specific criteria: it must orbit the Sun; it must have sufficient mass for its gravity to shape it into a nearly round form; and it must have cleared its orbital path of other significant objects. It was on the basis of these three objective criteria that the International Astronomical Union (IAU) formally retired, on August 26, 2006, the older and vaguer concept of a planet, traditionally associated with the idea of a wandering, luminous body visible in the sky.

The first eight planets of the Solar System (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) conform to the new definition. The ninth planet, the youngest of the bunch (discovered only is 1930), did not meet these criteria. “Pluto, under these terms, was reclassified as a ‘dwarf planet’ and became the prototype of a newly recognized category: Trans-Neptunian Objects [located beyond Neptune],” wrote the IAU board in Resolution B6.

In the same document, the entity clarifies that a dwarf planet, in addition to not being a satellite, must satisfy the first two conditions applied to planets, but is not required to have cleared its orbital path of other celestial bodies.

The resolution confined planetary status within the Solar System to eight known bodies. Had this change not been enacted, other Kuiper Belt objects—very similar to Pluto—would also have qualified as planets. One such case was Eris, a trans-Neptunian object discovered in 2005. With a mass greater than Pluto’s, Eris was briefly heralded as a potential new planet—until the IAU’s decision not only barred its planetary status but also demoted Pluto, reducing the official planetary count to eight.

The story above was published with the title “Orbiting Planet 9” in issue 351 of May/2025.

Project

The relevance of small bodies in orbital dynamics (n° 16/24561-0); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Othon Winter (UNESP); Investment R$5,073,662.49.

Scientific articles

SOUSA, R. R. et al. Reassessing the origin and evolution of ecliptic comets in the planet-9 scenario. Icarus. Feb. 19, 2025.

BATYGIN. K. & BROWN. M. E. Evidence for a Distant Giant Planet in the Solar System. The Astronomical Journal. Jan. 20, 2016.

Republish