FAMILY COLLECTIONBrentani with Isaias Raw: independence as from 1968 and life-long friendshipFAMILY COLLECTION

I met with Ricardo Brentani on November 23 to talk about research activities at USP’s School of Medicine at the start of the 1960’s. It was during this period that Brentani began his career as a researcher, alongside other young men and women who also became important scientists – such as Walter Colli, Erney Camargo, Mitzi Brentani and Sérgio Ferreira. FAPESP was also created during this period. It was precisely this coincidence between the start of the professor’s career and the creation of FAPESP that led me to track Brentani down, in search of memories on what scientific practice was like in São Paulo 50 years ago.

“The School of Medicine was of an international level”, he said at the start of the conversation. Three of the scientists who were responsible for the faculty’s ‘international level’ played a key role in Brentani’s education: the histologists Luis Carlos Junqueira and Michel Rabinovitch and the biochemist Isaias Raw. At my initiative, the conversation focused largely on the first of these, the school’s controversial senior professor of histology and embryology.

At the end of our meeting, the professor pointed happily to the A.C. Camargo Hospital’s financial results and told me about the new director that he had hired in Europe to head up the research center that is associated with the hospital. He also spoke with pride about FAPESP’s work over the last few years. Before I said goodbye, I told him that I would seek him out at least once more before completing my research project about science in São Paulo during the 50 years since FAPESP was first set up. I am left profoundly saddened by the fact that any further conversations are now impossible.

What was the outlook for research at USP’s School of Medicine when you first began your career?

In terms of medicine, it was on an international level. I mean you had [Luis Carlos Uchôa] Junqueira, Isaias [Raw]. And in parasitology – Samuel Pessoa put together a team that was second to none: the Nussensweigs, Luiz Hildebrando, Leônidas Deane and Erney Camargo, who was just beginning his career. In physiology, the senior professor was Alberto Carvalho da Silva and in addition you had Gerhard Malnic who was also just starting off. The chair of pathology was held by Constantino Mignone, who was always overlooked by everyone. One day I was in Washington having dinner with a very important pathologist when he told me that Mignone’s thesis on the physiopathology of Chagas’ disease, which was what earned him the chair of pathology, was a world classic – even though it was written in Portuguese. Clinical medicine and surgery also had good people, and the cardiology department was really advanced.

When did FAPESP begin to make a difference?

Right from its outset. FAPESP’s first chairman was Jayme Arcoverde de Albuquerque Cavalcanti, who at that time held the chair of biochemistry. FAPESP’s first head office was on the fourth floor of the School of Medicine. Cavalcanti was chairman and he lent his secretary to be FAPESP’s secretary. That’s how it started. Later FAPESP moved to Paulista Avenue.

How did you first get into research?

I started my degree course at the School of Medicine in 1957 and in the first year I found myself with a lot of free time and not much to do. So I looked for a research lab to see what it was like. The first professor I contacted, I am not going to say who, told me: “I don’t have time to waste on nonsense. Go and look for Michel [Rabinovitch], he likes children.” Then Rabino gave me a load of books to read, which were complicated and difficult. After I had read all of that stuff, he said: “Well, let’s get to work since I can see that you’re not going to give up…” Michel was extremely important to me. When he accepted me, I began to work on his things. Science is like that: many people don’t realize it, but there’s no democracy whatsoever. You have to grow in order to be able to work on the things that you want to. With Michel, I got published the first time in Nature, in my fourth year at university. I’m privileged: I have been published twice in Nature with my wife, once while I was a student and once with my daughter. Not everyone is so lucky. Then Rabino went off to work for the Rockefeller Foundation and I spent a period with Junqueira. While I was doing my internship with Rabino, I had made friends with Junqueira – who was my professor and who was always in the lab. It was a real pleasure talking to him, he was an amazing person, a great scientist, incredibly cultured, and so I was always his friend. He had some characteristics that those of you who know me would appreciate. For instance, he hit a professor from the School of Medicine. Naturally, he was expelled from the school. As soon as Juquita [José Ribeiro do Valle] heard about this, he accepted Junqueira at the Paulista School of Medicine, from which he graduated. From there he went to the United States to do a post-doc. At that time, it didn’t used to be called that. At the Rockefeller Foundation in New York, Junqueira became close friends with Keith Porter and George Palade [both of whom won the Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology] and took part in the development of the electron microscope. As a result, he became incredibly skilled in the use of the electron microscope. He was invited to return to São Paulo to take part in the competition for the post of Chair of Histology – as the previous holder had died suddenly. So he became a senior professor at a very young age and brought substantial funding from the Rockefeller Foundation to set up his lab. Junqueira’s histology department produced Ivan Mota, for instance, who discovered the mast cells and was a world class scientist, as well as José Carneiro. Nelson Fausto and Sérgio Ferreira were both trained by Michel, who was Junqueira’s assistant. The lab had a lot of microscopes as well as the School of Medicine’s first ultracentrifuge. This ultracentrifuge was Michel’s, and he learned how to put the machine together and how to take it apart, because back in those days there was no technical service department. The lab had everything that we needed in order to be able to do the research that we doing at that time.

And why did everyone stay in this laboratory?

It was the best set-up and best equipped lab, thanks to funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. After Rabino left, Junqueira told me that there was no way I could have a histology laboratory as a student. At that time, I had already met Mitzi [Maria Mitzi Brentani, his future wife]; she was going to start working with Isaias – who was the coordinator for the biochemistry department – and I went along with her, as a sort of freebie. The position of coordinator was held by an assistant professor who had not yet taken the exams to become a senior professor. Isaias was the last but one professor to hold the position of Chair of the School of Medicine. The last person to be awarded this title was Euriclydes Zerbini; after this everyone became a senior professor. Later on, in 1972, the Chemistry Institute loaned me to the School of Medicine in order for me to set up an experimental oncology department. From then onward, I spent my time at the School of Medicine, except when I had biochemistry classes, for which I had to go to the university campus. This resulted in me renewing my friendship with Junqueira.

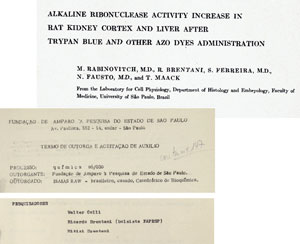

REPRODUCTION: EDUARDO CESAROne of Brentani’s first papers, published in the Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology in 1960; and the first grant he got from FAPESP in 1965REPRODUCTION: EDUARDO CESAR

What were his qualities?

He was a great scientist. At the end of the 1940’s, he and Torbjörn Caspersson, who was Swedish, separately showed where the cell produced protein, which was no small achievement. Afterwards he conducted pioneering studies of protein synthesis in the saliva glands. He always had a highly developed sense of curiosity and didn’t have any fixed field of research. He would show up all of a sudden with some new interest. For instance, he showed that the line that runs along the side of fish is in reality neurons that help fish position themselves in the water. Another discovery of his concerned the bombardier beetle. This creature secretes a mixture of hydrogen peroxide and concentrated formic acid that boils and burns. The accepted belief at the time was that the beetle had various glands that secrete the components and that the mixture occurred outside the beetle’s body; Junqueira showed that the creature has just one gland with an extremely thick membrane, and that the mixture is already boiling when it comes out. Another one of his traits was that he would get all excited at times when he was hot on the trail of some idea or other, and then he’d get thoroughly depressed when he had no idea to pursue. In 1975 and 1976, he was depressed. I had attended a lecture about a dye [for microscopy] that was called Sirius Red F3BA. I rang the factory and discovered that this was used to dye leather and that it was sold by the ton. When I said I would need 100 grams of it, he decided to give me a present of two 50 gram bottles. When they arrived, I went to prepare the slide [of collagen] with the dye, but it went wrong. I have always been clumsy, I have a lot of imagination, but I was never any good at the manual stuff. So I gave Junqueira an offprint about the dye, along with one of the 50 gram bottles and the slide that I had produced. He was always one of those guys for whom every little detail has to be perfect, absolutely spot on. Three days went by and he came back to me thoroughly happy, with a dazzling slide; he was really excited. This dye is an extremely long molecule, measuring 1,200 angstroms, with six negative charges spread about. For this reason, it sticks parallel to the collagen fiber, so that when you shine polarized light on it the dye becomes birefringent and emits light. For a decade or more, Junqueira and Gregório Santiago Gomes revolutionized histochemistry and the biology of collagen. They published 40 or 50 papers on the subject. One day he suddenly showed up in my office with a look of despair – his face was white and he appeared pale. What happened? I asked. “I’ve run out of dye!” I opened my drawer and gave him the other bottle. After Junqueira’s papers were published, the factory began to sell more dye in the form of 50-gram containers than it did by the ton: the entire world started using this method.

What were the topics of the histology laboratory?

Each assistant had his own line of research. So Ivan was studying the mast cells, Michel was studying renal physiology, José Carneiro, autograft, José Ferreira Fernandes was working on Chagas? disease, and Sakae Yoneda was studying embryology. These lines were in synch with world lines of research. Junqueira was very fond of comparative histology. From time to time, he had strange creatures there. He had a technician and Hanna Rothschild was also working with him. He did a lot of histochemistry to observe protein synthesis. He did a lot of stuff with the pancreas and the saliva gland. During the years that I spent in the histology area, the foreigners who came to visit the department came because of him, to spend time with him.

Was FAPESP also important to Junqueira?

With his ‘popular spirit’, Junqueira made lots of enemies. Some grants that he applied for weren’t granted. After that, he didn’t ask again.

And what about for your career when you first began to work as a researcher? How important was FAPESP to you?

I am very proud to say that I have never had a single request for funds turned down by FAPESP. In 1968, I was released by Alberto Carvalho da Silva. When I say released, what I mean is that up until then I carried out the research project, gave the whole thing to Isaias and he included my project along with one of his. This way I had what I needed without knowing how much. In 1968, Alberto told Isaias that it was time for me to start applying for funding myself. That’s how I got my first grant. Exhibiting my usual excessive level of honest, I said to him “Isaias, intellectually I have always been independent. Now that I’m also financially independent, I don’t think I need to put your name on my papers, what do you think?” Since he’s an amazing guy, he let out a laugh and said “You’re right”. Most professors would have said “You little punk, who in the hell do you think you are?” Isaias is special.

What topics did you work on in Isaias’ laboratory?

Mitzi and I got married in the fifth year of university, soon after we began working with Isaias. When we came back from our honeymoon in 1961, Isaias put us to work on synthesizing protein in test tubes based on cellular fractions. You have to bear in mind that the system [of coding proteins, the so-called genetic code] only began to be unraveled from 1962 onwards [by Francis Crick and Sydney Brenner]. So we had one helluva hard time to make things work. I was feeling despondent and Isaias said: “You’re good, don’t get so depressed, just move on”. We managed to get some results and showed that, extracting RNA from the nucleolus, the amount of synthesis increased. We spent 10 years of our lives showing that the nucleolus processes messenger RNA and that this is why the amount of synthesis increases. We were unable to explain the initial results; when messenger RNA was discovered, I realized that the nucleolus must be responsible for processing the messenger RNA. Everybody fell about laughing both here in Brazil as well as abroad.

What was the accepted belief?

In 1962, it was shown that the nucleolus produces ribosomal RNA, which is true. In people’s minds, each thing only performed one function, nobody imagined that maybe they did more than one thing. Five years ago, using yeast mutations, researchers showed that the nucleolus does indeed process messenger RNA – but they did not cite me. I wrote to the researcher. He replied: “But I was in kindergarten when you published this….”

How did the fact that the scientific community did not accept your conclusions affect you? Were you able to continue publishing?

Yes, the two articles that we published together in Nature were both about this subject. Yes, we were able to publish. But for instance, a paper that I wrote at this time, which was published in the Biochemical Journal, was refused. The editor’s letter said that the referees did not like the hypothesis. I replied: “I have re-read [the magazine’s notes on policy] and there it is written that you want papers where the experimental evidence supports the assumptions. It makes no mention whatsoever that the referees have to like it.” I spent an entire year arguing with the editor. Finally, I received an acceptance letter: “I am pleased to inform you that your paper has been accepted. P.S.: I continue to hate your assumptions”. I am not comparing myself to anyone else; I’m small fry. The major breakthroughs have always been received with profound disbelief. It was Machiavelli who wrote “there’s nothing more dangerous than going up against the accepted truth.”

Have you contradicted the accepted truth on other occasions?

Yes. There were some figures in the literature, but not a lot, which suggested that the polysomes that produce collagen formed very large aggregates. Contrary to the accepted belief – which is that three collagen molecules join up in the triple helix after being translated – I felt that the only possible interpretation for this ‘mega corncob’ was that the association of the three molecules was a premature event. If I was right, then it should be possible to purify polysomes using low centrifugation. I demonstrated and published this and spent 10 years trying to convince the scientific community. I would go to the Gordon Conferences [discussion forum for cutting edge research in the areas of biology, chemistry and the physical sciences] and everyone would say “here he comes again, with those crazy ideas of his”… We now know that there are 18 different characterized collagens, and everybody accepts without argument that the assembly takes place earlier rather than later. One day I went to dinner at Nelson Fausto’s home in Seattle, and there was a famous big-shot collagen specialist there. “You were right and we were all wrong. But don’t expect anyone to mention you because your articles are already 30 years old”. Fair enough. More recently, I came up with the theory of supplementary hydropacity in which nobody believes so far. Ok, Renata Pasqualini’s doctorate is in PNAS, Sandro de Souza’s doctorate is in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, and we published in Nature Medicine with Wilma Martins. There are now at least 90 papers showing that this works. And some of my papers are cited a great deal.