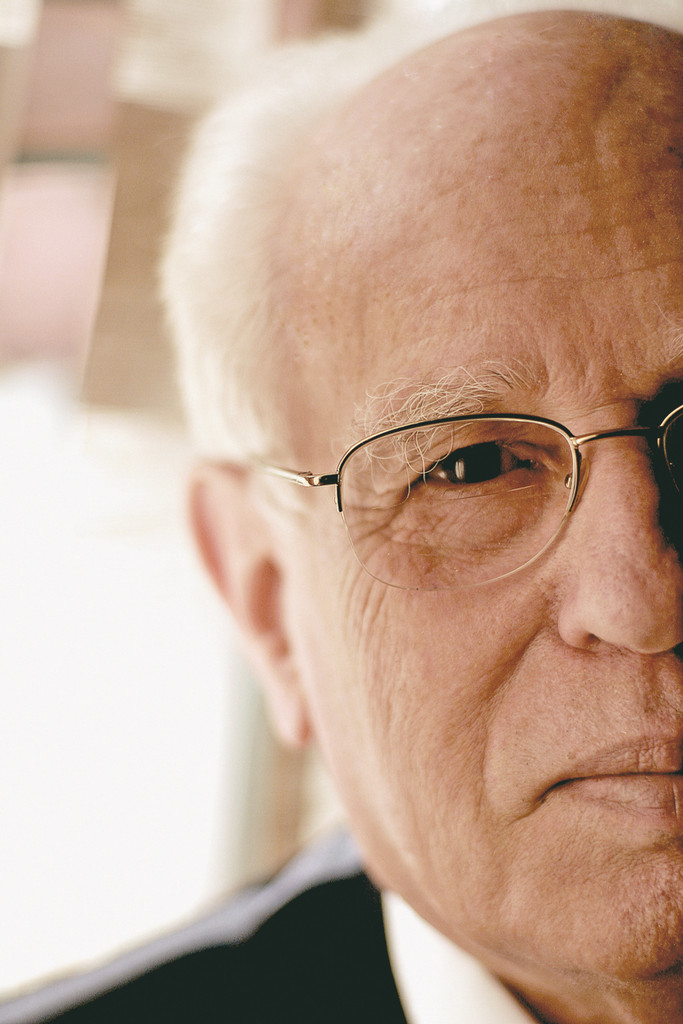

MIGUEL BOYAYANFirst of all it was Time magazine that in December 2007 mentioned the physicist and former Dean of the University of São Paulo (USP), José Goldemberg, in a list of worldwide heroes of the environment, in recognition of an article he had written in 1978 in the journal, Science, where he anticipated the environmental advantages of ethanol. After, it was the turn of the Asahi Glass Foundation, from Japan, which in June awarded Goldemberg its Blue Planet prize, with the right to 50 million yen (the equivalent of R$ 800,000), for “having made a major contribution to the formulation and implementation of various policies associated with improvements in the use and conservation of energy”, particularly for a concept formulated by Goldemberg according to which, in order to develop poor countries do not need to repeat the technological paradigms followed by rich countries. In the same month USP’s Institute of Advanced Studies arranged an open debate to discuss the future of USP and Brazil and to honor Goldemberg’s 60 year university career, which dealt with the topics he is interested in : science, energy, universities, technology and the environment. The wealth of tributes left the physicist happy but somewhat embarrassed. “This kind of thing is always embarrassing. Why do they choose you in particular if others also made a contribution?”

MIGUEL BOYAYANFirst of all it was Time magazine that in December 2007 mentioned the physicist and former Dean of the University of São Paulo (USP), José Goldemberg, in a list of worldwide heroes of the environment, in recognition of an article he had written in 1978 in the journal, Science, where he anticipated the environmental advantages of ethanol. After, it was the turn of the Asahi Glass Foundation, from Japan, which in June awarded Goldemberg its Blue Planet prize, with the right to 50 million yen (the equivalent of R$ 800,000), for “having made a major contribution to the formulation and implementation of various policies associated with improvements in the use and conservation of energy”, particularly for a concept formulated by Goldemberg according to which, in order to develop poor countries do not need to repeat the technological paradigms followed by rich countries. In the same month USP’s Institute of Advanced Studies arranged an open debate to discuss the future of USP and Brazil and to honor Goldemberg’s 60 year university career, which dealt with the topics he is interested in : science, energy, universities, technology and the environment. The wealth of tributes left the physicist happy but somewhat embarrassed. “This kind of thing is always embarrassing. Why do they choose you in particular if others also made a contribution?”

At the age of 80, married for the second time, the father of four children and grandfather of five, José Goldemberg from Rio Grande do Sul is still one of the main points of reference when it comes to energy planning in Brazil. He achieved this status in the 1970s, when after working for more than 20 years as a professor of nuclear physics his voice was raised in criticism of the construction of the atomic power stations that were being planned by the military governments. He was president of the Brazilian Physics Society and the Brazilian Society for Progress in Science (SBPC), positions that gave him the credentials to hold important positions after the return to democracy: president of the Companhia Energética de São Paulo, from 1983 to 1986, Dean of the University of São Paulo, from 1986 to 1989, Secretary of the Environment, Science and Technology and Minister of Education in the Collor government from 1990 to 1992, all without any break in his academic production. From 2003 to 2007 he was the State Secretary for the Environment. He is currently still active at USP, as a researcher in the National Reference Center in Biomass at the Institute of Electro-technics and Energy (IEE/USP), and as coordinator of the Bioenergy Committee of the São Paulo state government. In the following interview Goldemberg recalls his academic career, talks about the future for ethanol and nuclear energy and discusses the prospects for Brazilian universities.

The organizers of the Blue Planet prize highlighted your contribution to research into the rationalization of energy use with an emphasis on the leapfrogging concept, or “the technological leap” in energy that you formulated. What is the importance of this concept?

Until the oil crisis of the 1970s economists thought that per capita income was inextricably linked to energy consumption. This linear relationship was discredited in the self-same decade. I was working at Princeton at the time and we began to notice that the reason why energy grew along with per capita income was simple: the system had not been optimized. Light bulbs were inefficient, as were refrigerators and automobiles. When it was noticed that energy reserves were not infinite and represented a growing weight in the economy and personal spending people began to optimize and that is when energy and income growth were uncoupled. A very great effort was made in this sense in rich countries. It just so happens that I’m from a developing country. In a country like ours preaching that it’s necessary to use less energy simply doesn’t catch on. It even seems to be a way of keeping people in poverty. That’s when I noticed one of the reasons why this allegation was made; it was because every time something was set up in Brazil they used old technology. The World Bank used this as a strategy. It was imagined that developing countries ought to introduce tried and tested technology. If not there would be no one to carry out the maintenance. I saw that to continue going down this same path was unnecessary, that one could take a leap ahead; that’s where the name leapfrogging came from.

What examples would you give of a “technological leap”?

The best is the cell phone. As wireline telephone services are very dear (you have to install the cables) they’re often not appropriately supplied in developing countries. Today, a rural region can be served with an antenna when it would have taken years to supply it with cables. Look at the case of the steel industry. It was introduced into Brazil in Volta Redonda, which became a terribly polluted place. But then the local steel industry began to develop and steel mills became clean because Brazil was no longer buying from the United States, it was buying from Japan. Every concept attracts attention when you develop it. Now it seems trivial, but that’s the way progress is. It’s only trivial afterwards. Alcohol was also a way of leaping ahead. Brazil developed a renewable fuel to substitute gasoline. We’re not repeating the course of history.

In 1978 you wrote an article that has now been remembered by Time magazine as being prophetic, because it showed the environmental potential of ethanol. What prospects do you see for Brazilian ethanol?

Time put me up there as one of the heroes of the environment – as someone who sees what is going to happen in the future. I want to explain myself. There were other people involved in this alcohol program and they chose me. This type of thing is always embarrassing, but it’s other people’s perception. My point of view is the following: in 1978 ethanol was being promoted by the government because the price of sugar in the international market was low. Furthermore, Brazil had an enormous account for the importing of oil. Mill owners and some people from government thought that diverting a little sugar to produce ethanol would be a good idea because it would solve the mill owners’ problem and reduce oil imports. When I thought about it I asked myself: “There’s an advantage for the mill owners and for Petrobras, but what about from the environmental point of view?” I wanted to carry out a numerical exercise, which is something physicists know how to do. How much fossil energy is being used to produce ethanol? The 1978 work was just that: a calculation. We noticed something interesting. To produce a liter of ethanol requires approximately a tenth of a liter of fossil fuel. It’s not much and there’s a clear reason for that. The energy needed for producing ethanol comes from bagasse. In an alcohol distillery there’s no need to import fuel; the fuel is bagasse. Therefore, ethanol is fundamentally solar energy: the sun shines, the cane grows, you liquefy it using a chemical process and this generates ethanol. From the environmental point of view it’s great, because there are none of the impurities you get with gasoline and it contributes little to the greenhouse gas effect.

In the article you draw comparisons with other crops, don’t you?

Yes, and the comparison made it all very obvious. As corn produces no bagasse you have to bring in energy from outside the distillery. Corn ethanol is produced in the United States using coal. Of course, there’s an advantage because you can’t put coal into the engine of your automobile. But from the environmental point of view it’s six of one and half a dozen of the other.

What are the prospects for ethanol in the medium and long terms?

At the moment ethanol takes up just a small fraction of the land. Agriculture in Brazil occupies an area of 60 million hectares. Some 6 million are used for sugar cane, in other words, 10%. Half of this is used for ethanol. It’s not the impression you get because it’s very concentrated in the State of São Paulo, but looking at Brazil as a whole it’s not very much. Our ethanol substitutes 50% of the gasoline used in the country, which corresponds to 1.5% of the gasoline used in the whole world. What’s going to happen ten years from now has already been more or less outlined because the system is expanding. Ethanol from Brazil, which represents 1.5% of the world’s gasoline consumption, is probably going to rise to 7% or 8%. There’ll be enough sugar cane for this, if we use probably 10 million hectares. It is already expanding, but it’s on pasture land where cattle are being reared in an extremely inefficient way. The idea that alcohol is going to lead to the destruction of the Amazon or make advances on other crops is not what’s happening in practice. If we think about substituting 100% of the world’s gasoline then that really is a worrying situation. Over the next ten years I think that Brazil is still going to be in a comfortable position. In the United States the situation is very much more problematic.

Miguel BoyayanBecause of the technology they use and the subsidies…

Miguel BoyayanBecause of the technology they use and the subsidies…

And also because they have nowhere to go in terms of expansion. North American agriculture occupies almost 100 million hectares -something slightly more than double the area occupied in Brazil. I asked an American friend: “Why don’t you expand?” He replied: “Expand where?” We don’t realize that the United States has huge deserts – practically the whole of California and Nevada is desert. There are enormous mountain ranges. Brazil has considerable capacity to expand.

But we have technological challenges to overcome with regard to ethanol. How do you see the prospects for second generation ethanol extracted from cellulose?

I think that on a horizon stretching beyond ten years we’ll have second generation technology. The United States is in a difficult position because it’s relying on the second generation happening over the next three or four years. I don’t think that’s going to occur.

Over the last few years Brazil has not invested as much as other countries in ethanol from cellulose…

Naturally. After all, Brazil’s first generation ethanol is successful unlike that of other countries. Productivity has grown by almost 4% a year over the last thirty years, if you consider both industrial and agricultural gains. And without genetic manipulation, which is what is now being looked into. Everything we have is first generation; second generation is cellulose. Cellulose is formed from a long sucrose chain and the problem is breaking down cellulose into sucrose in order to ferment it. Brazil is going into this now. There’s a lot of work being done on second generation ethanol, but it’s still fragmented. There a lack of articulation and above all we need the pilot plants. It’s one thing carrying out an experiment in a laboratory and quite another producing on a large scale. FAPESP has launched a bioenergy program, Bioen, to accelerate development. There’s also a program under preparation that the State government should launch, and which is big and would at least double the funds that FAPESP is investing in this area; this is also being done to accelerate the development of second generation technology. I’m the coordinator of the State Bioenergy Committee, which was set up by the governor for this specific purpose. Our report is in the final preparation phase and the government is likely to take measures in this direction shortly. The idea is to encourage second generation research in a very significant way.

I wanted to talk a bit about the start of your career. I haven’t understood the order of events of your 60 years at USP, because you enrolled in the university’s physics course in 1946, 62 years ago.

The reply is the following: I only became a scholarship-holder in 1948 and started working for USP.

What was the university like at that time?

I came to São Paulo in 1946.I studied at a very good high school in Porto Alegre, the Julio de Castilhos State High School, which was the cradle of positivism in Brazil. When I was at school it was already obvious that I wanted to study physics. And the place that had physics in Brazil was USP. That was in 1946. The university had been set up in 1934 – it was 12 years old. At the time there were still some of those foreign professors here who had come to Brazil to escape Nazism and Fascism. In the Physics Department of the Philosophy, Science and Arts Faculty (FFCL) there was an Italian professor, Gleb Wataghin, who ended up lending his name to the Physics Institute at Unicamp. I think there was some historical injustice in that, because he should have lent his name to USP’s Physics Institute. Wataghin had been a student of Enrico Fermi, who played a very important role in developing nuclear energy. He was an individual with a very good vision of physics and that’s what attracted me to it. There were other, second generation professors, like Mário Schenberg and Marcello Damy de Souza Santos. There was a feeling that science was something living at the time. Some of these professors had already been abroad and had already published works and practiced science in the first world. I began to work with experimental nuclear physics. The FFCL was still in its ascendancy phase and struggling to compete with the traditional faculties. There was a feeling of being in the midst of a battle: the Law faculty was conservative, the Polytechnic wanted nothing to do with science, etc.

At the same time these units, which already existed before USP was founded, were attracting more students than the courses offered by the FFCL, weren’t they?

Yes, this was a heroic time. The success of the university’s evolution led to an improvement in all faculties. The university reform of 1968 helped this happen. But soon after, in 1952, I went abroad and started to develop a career partly there and partly here. At the time if you chose a career in the science area this was considered to be choosing poverty, even by your family.

And was it? Even today the academic career has rewards that are not exactly material…

That’s more recently. USP, of course, was a pioneer in something fundamental. It created the exclusive dedication regime. Listen to what I, as a former Dean, am saying: if I had to point to one thing that made USP viable I’d say it was the exclusive dedication regime. Without this it wouldn’t have been be possible to develop scientific activities, because individuals in order to maintain themselves needed to give lessons in a series of places. After the various reforms that the university went through and some very aggressive deans (in the good sense of the word) like Antônio de Ulhôa Cintra and Miguel Reale, USP grew and gained more resources. And finally, at the time when I was the dean, we managed to achieve financial autonomy, which made a huge difference. This doesn’t mean that the university has to split itself off from the rest of society and from government, but it’s essential that it knows what funds it can rely upon.

Why did you change career direction in the 1970s, exchanging laboratory physics for an interest in energy?

In the mid-60s I spent two years at Stanford University, which at the time had the best nuclear electron accelerator and I carried out work that had significant repercussions. I received various invitations to work abroad in very good positions: I was invited to be a full professor at the University of Toronto. I also received an invitation from the University of Paris and I went there. It’s possible that if significant events had not occurred in my personal life I’d have become a full professor at the University of Paris or Toronto. But my first wife died. I came back to Brazil with my young children and thought that I needed to build my life in Brazil. That was more than 40 years ago. I was an assistant professor and sat the admission exam to become a full professor at the Polytechnic School. When political repression by the military regime began I already had administrative responsibilities. I became head of the Institute of Physics that was set up in 1970. It brought together all the physics activities of USP, including the Polytechnic School

Is that when your political activism started?

It was not party political activism. But I couldn’t turn a blind eye to what was happening in the country and I started getting involved in society issues. I became president of the Brazilian Physics Society and then president of the SBPC and I got heavily involved in the nuclear debate. Because of my educational background I knew what was being discussed. Then Franco Montoro was elected governor of São Paulo and he made me president of Cesp. Right after that I became dean. One positive thing is that I managed to keep on with my scientific activities. There was no break in my list of publications. The only thing that happened was that there was a time when I stopped publishing in physics journals to contribute to publications that had a broader reach.

In the July edition of Pesquisa FAPESP, the former Planning Minister, João Paulo dos Reis Velloso, dealt with a series of positive changes in the Brazilian academic environment that were implemented at the time of the dictatorship, such as the post-graduation system. In as much as you spoke out against the regime at that time do you agree with this analysis?

Despite the repression the military movement had strong modernizing components. Perhaps because of this the relationship of the military with science and technology has always been doubtful and complex. They wanted a great and militarily strong country and they had the good sense to recognize that to get there they would need scientists. They started the nuclear program – wrongly, but they started it – and the space program, and they ended up accepting those ideas for post-graduation, which were effective modernization measures. But the military government was very worried about the threat of communism and with the specter of the Cold War. They persecuted professors, like Mário Schenberg, and retired Fernando Henrique. But their focus was on the social sciences. Several of us, however, didn’t need to leave the country, including me. I was openly opposed to the nuclear program. People used to ask me: “The government retired off everybody, why didn’t they get rid of you?” They must have thought that by eliminating this type of person they would be losing a type of competence they would need. But the system they created ended up very distant from industrial activity. From this point of view it reminds us a little of the now extinct Soviet Union, which had relatively well looked after scientists but who were kept at a distance from industry. Although it became a great military power it was a third quality power as far as consumer goods were concerned. Here in Brazil we didn’t get to this point, but the scientific system is still remote from activities on an industrial scale. I think this problem is linked to this inheritance of ours.

Miguel BoyayanIn the 1970’s you spoke out strongly against the construction of nuclear power stations, which today are beginning to be recommissioned in various countries. Would the nuclear energy option be convenient for Brazil today?

Miguel BoyayanIn the 1970’s you spoke out strongly against the construction of nuclear power stations, which today are beginning to be recommissioned in various countries. Would the nuclear energy option be convenient for Brazil today?

In the 1970’s I was opposed to nuclear development on a large scale and I was fully convinced that I was right. In 1992 Rio-92, the United Nations Conference on Environment, was held. This conference lasted 15 days and I was there (I was the Secretary of Science and Development in the federal government and also looked after the Environment). I was in Rio walking along the sidewalk on the beach front and met General Costa Cavalcanti, who had been the Minister of Mines and Energy and Homelands Minister in the military governments. He said to me: “Look here, professor, you people played a very important role in energy development in Brazil, bigger than you think. In 1975 I was the president of Itaipu Binacional and we were beginning to build Itaipu. The great discussion within government was if we should finish Itaipu or dedicate funds just to the nuclear area. The opposition of scientists reinforced our position within government”. It was an unsolicited testimonial and showed that we were right. The attempt to introduce nuclear energy into Brazil then was not timely. There were these enormous possibilities, like Itaipu, which is the world’s largest hydroelectric power station. Now 30 years on nuclear energy is being reassessed. But it’s still extremely expensive because of its complexity and concerns with safety. It undoubtedly has its advantages. It emits practically no greenhouse gases. Objections of an environmental nature have reduced because since 1986 there has been no major accident. But I believe that the time is not yet right for Brazil. If the government puts a large amount of money into nuclear energy which is dear it will fail to do other things.

And hydroelectric power stations in the Amazon? Do you think the time is right for them?

Yes. I think the use of the hydroelectric potential of the Amazon (not all, but part of it) is inevitable. But we have some problems: they’re very far from the major consumer centers and therefore transmission lines have to be built and the energy will not be cheap. But there’s no alternative. There’s also the environmental problem. It needs to be done correctly. Environmental problems always exist, because nothing can be built without changing the environment. We have to find ways of minimizing the impact or, if this is not possible, offering compensation.

When you were the Dean of USP the by-laws were rewritten and at the time this helped inject new life into the university. Now they’re talking about reforming them again. What do you think of this debate?

At the time there was a lot of pressure for a greater power sharing, just like there is now. It was a discussion about the management of power and this is naturally very closely linked to what happened in 1968, when ideas of an equal say in management first came up. Having an equal say in management doesn’t work. It might satisfy political or corporate groups but it doesn’t solve the university’s problems. What a university needs is management that works. In the 1988 reform we extended the participation of student bodies a lot. The participation of students and entry level teachers was expanded. But management clearly continued in the hands of the more experienced and permanent people. This is still valid. Having a large participation by students who leave after five years is problematic. And employees ended up seemingly closely linked to political parties, which is very bad. I’ve not been following the new by-laws in detail but I thought that the matters that were brought up seemed like déjà vu. I’ve seen no very creative idea that will help to rejuvenate USP. I think there are more important problems and it’s not going to be by changing the power structure that they?re going to be resolved.

If you had to mention a problem that needs to be faced up to, what would it be?

Bureaucracy and lack of leadership. The university ended up being slow; it’s like a little old lady. People complain of the slowness of the processes and the bureaucracy involved, which has increased over the years. This has little to do with the problems in the country. Since corruption has become an endemic problem in Brazil more and more controls are continually being invented – and the more controls that appear the slower things become.

At the time you were Dean there was that famous uproar about the publication of a list of professors who had produced nothing academically, a list which came to be known as the “list of the unproductive’. How do you assess that episode today?

I see it as being extremely positive, because it introduced into the university the idea that there’s a need for measurement. If there’s one characteristic that has guided all of my life’s work it is the concept of merit and quality. A teacher needs to produce and be evaluated by independent judges. That’s the way it is in developed countries. At the time there were sectors in the university that published little and refused to be evaluated. They claimed that their evaluation was done internally, within their own departments. This created favoritism. This scenario has changed completely, not just within USP but in all Brazil. Today, if you’re a professor from USP, the Post-graduation Committee, Capes, the CNPq and FAPESP are the whole time asking you to prepare annual reports showing what you’ve published. The mark that Capes gives depends on the level of the publications (there are publications that are worth something and others that are not worth anything) and it’s most sophisticated. From this point of view the battle for measuring and evaluating quality has been won.

What’s your opinion of the Rio-92 Conference?

It was important and opened up the way to a new vision of environmental problems, which started being the responsibility of governments. The fact that governments had to take measures was clearly laid down at the time. So much so that the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 was a direct result of the 92 Conference. With the difficult stance adopted by the United States implementation of the agreements suffered an enormous delay. There’s an on-going struggle. I’ve accompanied this struggle and I’m convinced that Itamaraty is not sufficiently pro-active with regard to these issues.

What stance were you expecting from Brazilian diplomacy?

The United States refused to sign the Kyoto Protocol for the following reason: they don’t want to take measures to reduce emissions if others don’t take them, including developing countries. Why? Because if they alone take them it’s going to immediately create a trade competitiveness problem. Some products are going to be dearer in the United States than in other countries. On the other hand, developing countries argue: “That’s not fair because we came late to development and now we have the right to more emissions”. It just so happens that there’s no more room for this. China is emitting as much as United States. It doesn’t matter if the per capita consumption is different. If you put yourself in the place of the atmosphere what’s coming out of China even exceeds what’s coming from the United States. Brasil is relying on an obsolete argument, that historically we’re not responsible for the problem and therefore we’ve got the right to develop in this way. I remember my concept of leapfrogging: the idea that Brazil can’t grow if it adopts emission reduction targets is not true. It just has to adopt modern technology. We have a clean energy matrix and the government could take a more proactive position. Brazil is giving a helping hand to China; it’s not doing itself any favors, except as far as what happens in the Amazon. And what’s happening in the Amazon is a shameful situation that has got to end.

When you were with the Education Ministry (MEC) you had the federal universities under your command. Today they’re trying hard to increase the number of places. There’s a program for giving access to more people. Are they in a position to grow with all the characteristics of research universities?

As the Minister of Education I tried to apply the USP model throughout Brazil. I also tried to give federal universities a little more financial autonomy. It didn’t work. From this point of view my management did not produce results. I thought that without financial autonomy the dean is a third category MEC employee. Deans were always in my office saying that their funds had run out. It was true because there was inflation. As it was very difficult to arrange money within the government they used to go to the Senate and they used to manage to get amendments approved here and there. In other words, they had become luxury “fixers” whose job it was to arrange more funds. This prevented them from doing any planning. In the process I discovered that these universities in fact didn’t want autonomy. If they happened to get to know an influential senator they could get special funds. I remember one specific case in which I’d given money to a certain university, over and above its budget, in order for it to build a library. A few months later I went there to see the library; it hadn’t been built. The money had been used to build a student restaurant. In the dean’s view the food-tray was more important because the students were pressuring him. I said to him: “Quite; but this is not the Ministry of Social Assistance”. I learned that the USP model cannot be applied to all federal universities.

Why not?

The USP model is an elite model. And it’s not because I recognize it as elitist. It’s just that 100,000 students a year want to go to USP and there are only 7,000 vacancies. So there has to be selection. The others go to private universities. The impression I have, and I share it with colleagues that have dedicated themselves more to this, like Eunice Durham, is that the Brazilian university system needs to be reconsidered. Besides USP we have few universities of international standard, like Unicamp. The private universities took two thirds of the students. The federal universities were in limbo between these two categories. They were unable to transform themselves into research universities, neither did they dedicate themselves to mass teaching. Some of my colleagues think that we should create colleges here in Brazil; the idea that all universities in all states should be the same as USP, at least as a goal, is unrealistic.

Miguel BoyayanYou were part of the Collor government, which was heavily criticized by the scientific community because of its initiatives, like the attempt to do away with Capes. How do you assess this period?

Miguel BoyayanYou were part of the Collor government, which was heavily criticized by the scientific community because of its initiatives, like the attempt to do away with Capes. How do you assess this period?

As far as the environment is concerned the Collor government played a good role. It supported the Rio-92 Conference. At the time I’d just been named Environment Secretary, with a status equivalent to that of a minister. It was a great time. We created contiguous Indian reserves, when many people wanted to reduce them in size. I think it was also good in the science and technology area. We did away with this hidden business of producing nuclear arms and we ended the market reserve in IT, which helped modernize the country. This question of Capes was within the Ministry of Education’s sphere and was defined before the government began. People who came from outside thought there was duplication between Capes and the CNPq, because the two gave scholarships to study abroad. That was a business administrator’s idea; I have two people doing the same thing – fire one. It was subsequently all clarified and the government reversed its decision. I didn’t know Collor before his government began. I received a phone call on 14 March, the eve of the swearing-in ceremony. There were less well-known episodes. At a particular moment in time the government was thinking about amending the Constitution in an effort to modernize the country. Various proposals were put forward and one of them suggested the elimination of free university education. I violently opposed it within the government and the idea was abandoned.

This was at what point in the government?

Half way through 1991. Because 1992 was taken up with the crisis that led to impeachment. But I remember that I argued the point and the idea was abandoned. Economists think like this: “Ah, free education is elitist”. Thinking that the problems of universities will be resolved with students paying is a completely unrealistic idea. These are things that appeared at the time but the presence of people like myself and Professor Eunice Durham was important. And obviously we had absolutely nothing to do with Collor’s corruption. It involved other areas. And it was not because of our virtue. In the area I was working in there was not enough money to attract the interest of those people.

Did the fact that the Collor government ended as it did prejudice you in any way?

I don’t think so. I was the only minister that resigned in the midst of the crisis. In September it was obvious that Operation Uruguay was something set up and I resigned. At the time no other minister did. The only impact that resulted from my having gone into the federal government was that there was an incompatibility with some university colleagues and with the SBPC. At the time the board of the SBPC issued a statement associating itself with the proposals for impeaching the president. I was the minister and I went to the board meeting to explain that I was there as a scientist, that I had become a minister at the choice of the president and I thought the SBPC had no place manifesting itself with regard to political matters. It asked for impeachment and a little while later I resigned. In my opinion the SBPC was not created for this, but to defend scientists and science. It has no business getting involved with government, which is something that has occurred recently and something I’m not at all pleased about. I got a little bitter about it, but I don’t think it prejudiced me because I’ve worked with several governments. The Fernando Henrique Cardoso government, however, systematically avoided me. In 2003 governor Geraldo Alkmin invited me to be the State Secretary of the Environment.

In this interim period did you dedicate yourself to your academic career?

It was a good time. First I went to Switzerland and then to the United States. I wasn’t there the whole time. I was always coming and going, but I stayed in Switzerland a year.

The speeches of the IEA that paid tribute to you dealt with various subjects like science, energy, universities, technology, environment and the future. Do you think that these topics summarize your concerns and your interests or is something missing?

No. The organization tried to promote a discussion in each of the areas in which I’ve worked. Naturally the questions about the future went unanswered. Something that came out of the symposium, however, was a discussion on what needs to be done over the next ten years to move the university from 150th in the international ranking to 50th. I think it’s a good target.

Is it possible?

I think so. But this is also going to depend on boldness. The fact is that the university is still a long way from the production sector, unlike what happens with major research universities abroad. The Brazilian university system is growing but it’s not managing to meet the interests of society.