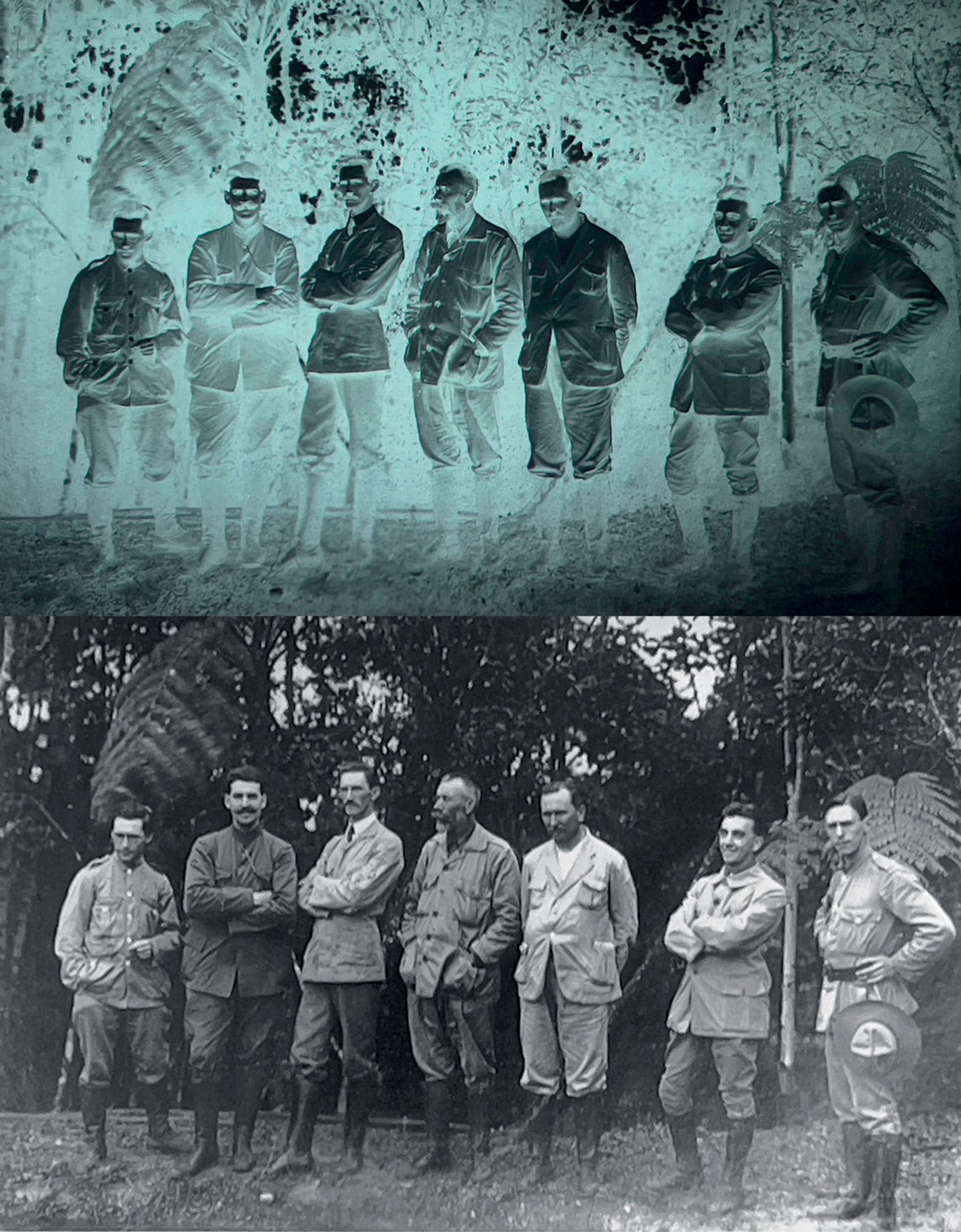

Acervo e Memória JBRJA glass negative and a copy on paper with gelatin and silver. From left to right: Paul Brien, zoologist; Paul Ledoux, botanist; Frederico Carlos Hoehne, Brazilian naturalist; Jean Massart, naturalist; João Geraldo Kuhlmann, JBRJ naturalist; Raymond Bouillenne, botanist and photographer; Alberto Navez, botanistAcervo e Memória JBRJ

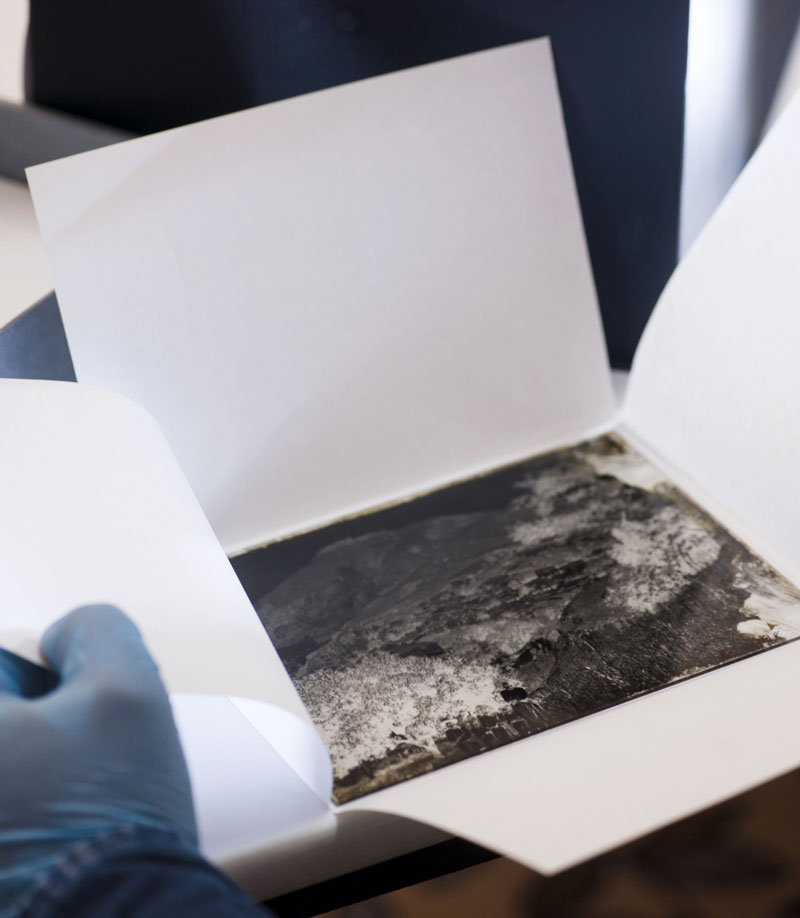

Free from the layers of dust and mold that had built up over the decades, 3,556 glass photographic negatives produced between 1910 and 1961 are now wrapped in silky white paper, packed in cardboard boxes stored inside steel cabinets in the glazed building at the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden (JBRJ) that has housed the photographic collection since 2021. Each plate weighs between 47 and 140 grams, almost as much as a cell phone.

Once organized, this rare collection of fragile plates will serve as the basis for academic research and reveal people who have been erased by time, such as photographer João dos Santos Barbosa (1895–?), who produced at least 419 negatives between the 1940s and 1960s. At other institutions, this type of material is not always carefully preserved and publicly accessible.

The glass plates rescued by the JBRJ team are 2 millimeters thick and come in three different sizes: 9 by 12 centimeters (cm), 13 by 18 cm, or 18 by 24 cm. In contrasting black and white, they depict exsiccates (plant samples), plants seen under a microscope, research instruments, managers, employees, the so-called arboretum of the Botanical Garden itself (an area currently home to around 9,000 species of plants from all over the world), and scientific expeditions to the Amazon or the Central-West region.

“The photographer had to think long and hard before pressing the shutter, because the material used was imported and expensive,” says photography curator Márcia Mello, who coordinated the conservation team for JBRJ’s historical collection. “We can feel the formality in the result. The photos are incredibly beautiful.”

The glass negative technique succeeded the daguerreotype, invented by the French stage designer and painter Louis-Jacques Mandè Daguerre (1787–1851). Announced in 1839, it consisted of a copper plate covered with a layer of polished silver; a mixture of mercury and silver formed the light areas and silver on its own formed the dark ones. The first glass negatives, in 1848, used albumen, a protein from egg whites, to make the silver salts adhere to the glass. The photo required a 5 to 15-minute exposure.

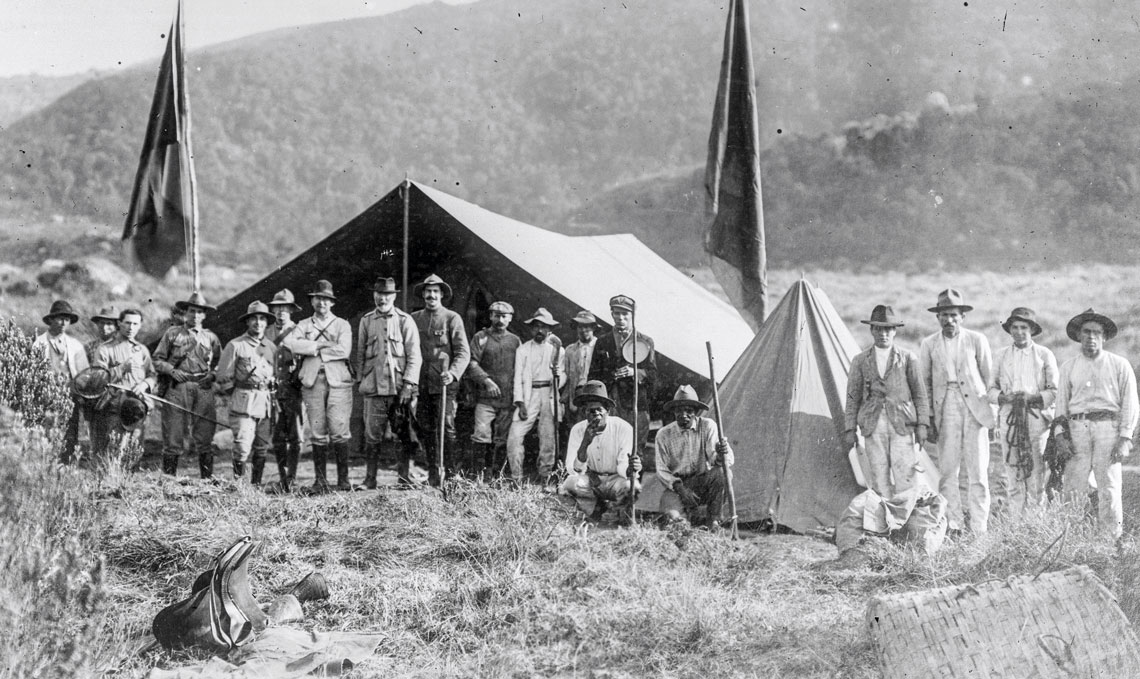

Acervo e Memória JBRJEncampment for the Belgian expedition to northern Brazil in 1922Acervo e Memória JBRJ

In 1851, English sculptor Frederich Scott Archer (1813–1857) introduced replacing albumen with collodion, a mixture of cellulose nitrate, ether, and alcohol. The photographer bathed each plate in a gelatinous emulsion containing cellulose nitrate diluted in ether and alcohol, placed each plate in the camera on a tripod, and had to take the picture before the gelatin dried.

In 1871, English physician Richard Leach Maddox (1816–1902) began using gelatin to which the silver salts adhered. When gelatin was used, it would swell, allow the salts to react, and then return to its original state. But there was still one limitation: the glass was heavy and fragile.

In 1885, to broaden the use of photography, North American businessman George Eastman (1854–1932), founder of Kodak, introduced roll film with paper that had been treated with gelatin and saturated with castor oil to improve clarity when developed. Three years later, he developed a camera with a roll of film for 100 photographs. Once the photos were taken, the camera was sent to the factory and the negatives were developed. Then, the photos were printed on paper and sent to the photographer, along with another camera containing film.

Acervo e Memória JBRJThe technique accentuates contrasts and details, as seen in the image of this flower, from the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden’s online collectionAcervo e Memória JBRJ

Some of the JBRJ negatives (1,106) are featured in the online archive. “It is vital that these materials are accessible by the general public. They can’t be hidden away,” emphasizes Raul Ribeiro, head of the museum and collection division at JBRJ. With a degree in social communication, he also manages the material that is constantly arriving at JBRJ. “We recently received 2,000 negatives on the anatomy of wood, produced by Raul Dodsworth Machado [1917–1996], one of the pioneers in electron microscopy at JBRJ,” he says.

Developed in the JBRJ laboratory, the glass plates wandered about for decades, bouncing between rooms with inadequate conservation conditions. “Under extreme heat, gelatin melts and the image is lost,” says Ribeiro. When researching the collection’s history, he discovered that two employees, brothers Domício and João Carlos Vieira (birth and death dates unknown), found the boxes containing the glass plates in 1980 and, with management’s support, rescued the material.

In 1989, JBRJ received funding from the now-defunct Vitae Foundation and the dozens of boxes containing the negatives went to the National Arts Foundation’s Center for Photographic Conservation and Preservation (CCPF-FUNARTE). “It was one of the first projects of its kind at CCPF,” says Sandra Baruki, a member and later coordinator of the Center. An architect by trade, she knew it was fragile material: when she was a kid, she saw her grandfather, photographer Octaviano Serra (1904–1979), in Corumbá, in Mato Grosso do Sul, produce this type of photo.

The CCPF team found 40 negatives stuck together and 88 broken. “In the late 1980s, we knew little about how to clean, preserve, and mitigate damage to the negatives, but we studied and learned, with guidance from experts from Brazil, Portugal, and the United States,” recalls Baruki.

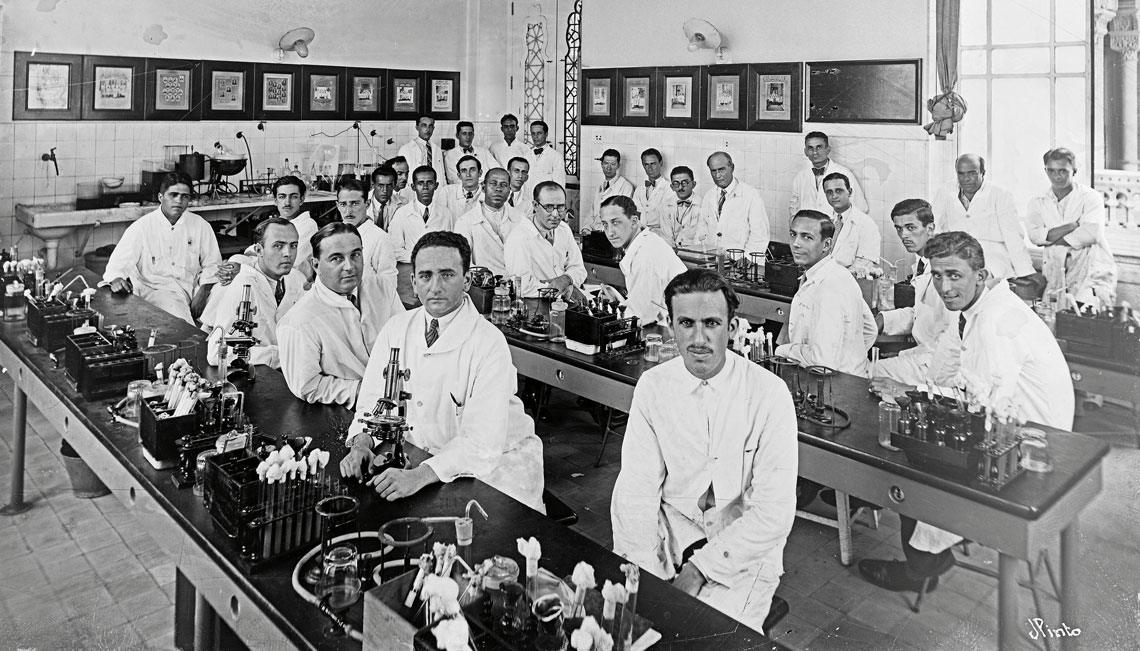

The Oswaldo Cruz House's ArchiveCourse at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute, in Rio de Janeiro, in 1931The Oswaldo Cruz House's Archive

Budget restrictions, which made it difficult to buy special film to duplicate the glass plates, prompted an innovation: CCPF photographer Francisco Costa created a method of photographing the plates directly onto flexible cellulose acetate film, used in cameras from the 1940s until the spread of digital cameras in the 2000s. Then, the film underwent a chemical bleaching process, similar to the one used to produce slides, and resulted in flexible negatives, used for consultation and to avoid handling the originals. The collection returned to JBRJ in 2000 and, in 2021, was digitized and stored in steel cabinets in the newly renovated warehouse, with the support of the Rio de Janeiro Research Support Foundation (FAPERJ).

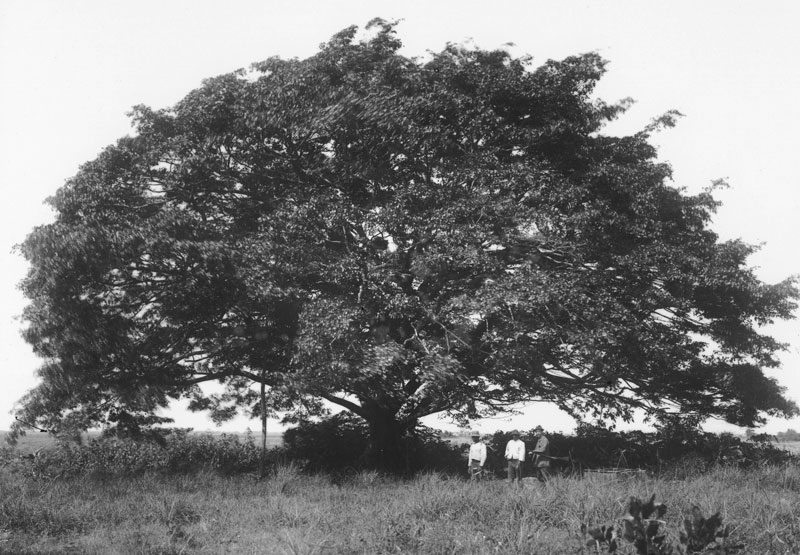

In his master’s thesis, completed in 2023 at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation’s Oswaldo Cruz House (COC-FIOCRUZ), Ribeiro examined the 16 negatives produced during the so-called Belgian Mission, an expedition formed by Belgian biologists who arrived in Rio in August 1922. With the help of JBRJ botanists, they sought to understand the tropical forests and collect materials for courses at the University of Brussels. In January 1923, after exploring the states of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, the group’s leader, Belgian naturalist Jean Massart (1865–1925), left Salvador to return to Europe; his companions headed north and, until May of that year, visited Pernambuco, Ceará, Pará, and Amazonas.

“We need to examine the images in the context of other documents,” says JBRJ historian Alda Heizer. When she consulted the Belgian Mission negatives before they were organized, she fell for a red herring: “I thought the trip would emulate the style of [French anthropologist Claude] Lévi-Strauss [1908–2009], who crossed the Southeast and Central-West of Brazil between 1935 and 1939, since the Belgians also took photos of the day-to-day life of the communities they visited,” she says. However, after reading the reports and field logs, she concluded that some photos, such as that of a Black woman in front of a house, were not anthropological, but instead expressed the Belgian travelers’ interest in the objects and structures made from plants.

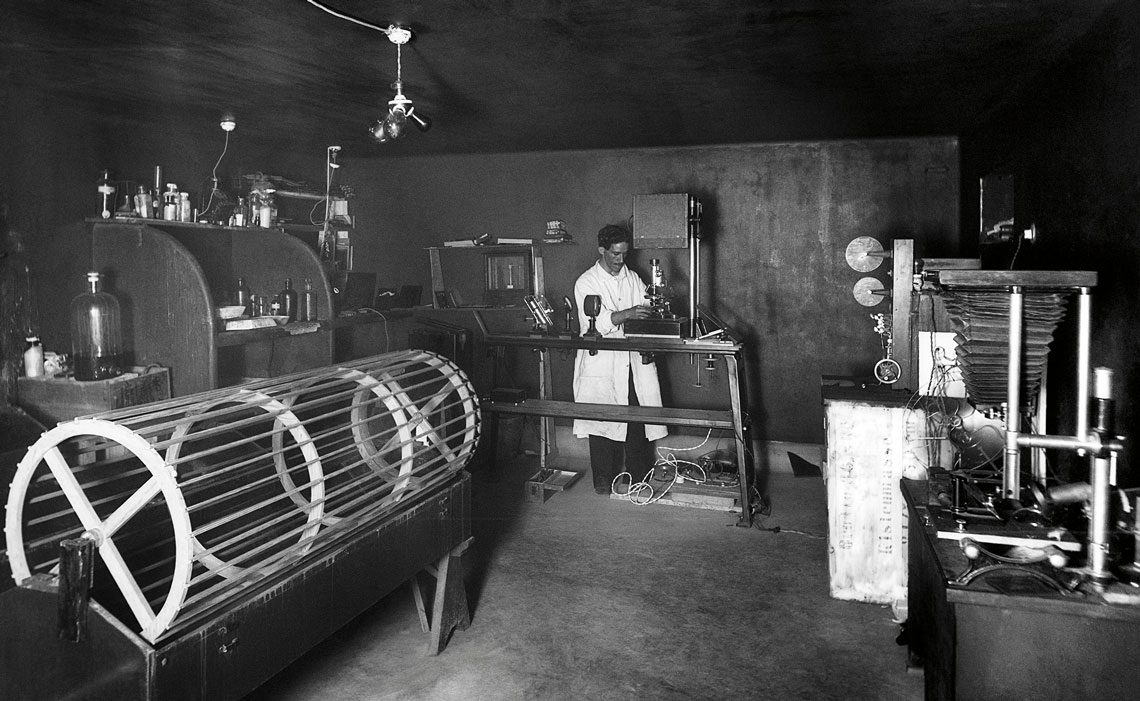

The Oswaldo Cruz House's ArchivePhotography laboratory at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute in the 1910sThe Oswaldo Cruz House's Archive

“The images speak volumes of the techniques used in the photographs and the values of an era,” she says. “In the reports and logs from the first decades of the twentieth century, such as those from the Belgian Mission, gardeners and tradesmen are addressed only by their first names, thus reflecting science that is centered on the scientist.

Patients, brains, and crime scenes

Other similar collections have been found in various states of repair. The COC-FIOCRUZ collection, organized starting in 1986, consists of 7,680 plates depicting researchers, laboratories, objects, patients, facilities, microscopes, construction of the current FIOCRUZ headquarters, and expeditions to the Northeast, North, and Central-West regions. One of the main photographers was Joaquim Pinto (1884–1951), who worked at what was then known as the Oswaldo Cruz Institute from 1903 to 1946.

“There was a laboratory and substantial investment in photographic production, which was seen as adjunct to scientific work,” recounts historian Aline Lopes de Lacerda, of the COC-FIOCRUZ Archive and Documentation Department. The collection is digitized, which facilitates research such as that of museologist Lucas Cuba Martins. In his master’s thesis, completed in 2023, he examined 529 images of anatomical parts produced between 1900 and 1960, when the institute stopped using glass negatives and replaced them with flexible and roll film.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPGlass negative in a special paper envelope, at the Ipiranga Museum, in São PauloLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

At the Emílio Ribas Museum of Public Health (MUSPER), affiliated with the Butantan Institute, the 1,100 glass slides, produced between 1922 and 1958, depict images of patients undergoing treatment for leprosy or mental illness, microscope slides, outpatient clinics, and laboratories. In 2014, when she first encountered the collection she would eventually manage, sociologist and documentation analyst Maria Assad was surprised by the images of histological brain slices and crime scenes — as she later discovered, they were related to psychiatric and mental health services in the first half of the twentieth century in São Paulo.

“The photographic collections began to be seen as documents from the 1990s onwards, because prior to this, they did not hold the same weight as textual documents, despite being important for supporting investments in buildings and equipment and for monitoring clinical cases,” says Assad, based on his master’s research on the treatment of public health images, completed in 2019 at the University of São Paulo (USP).

As the MUSPER collection is still being treated, the images can only be consulted in person, under the supervision of a specialist from the museum’s team. The 7,000 glass negatives, give or take, from the Biological Institute, produced between the 1920s and 1940s by Alberto Federman (1887–1958), are also not digitized; the 2,400 negatives from the former Botanical Institute (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 187), incorporated by the Environmental Research Institute (IPA), also in São Paulo, are digitized but are not online. The Ipiranga Museum of the University of São Paulo (USP) offers access to 2,855 negatives produced between the 1890s and 1940s, depicting paintings, furniture, documents, the museum’s beginnings, painter Benedito Calixto (1853–1927), inventor Alberto Santos Dumont (1873–1932), and construction of the Madeira-Mamoré railroad.

Emílio Goeldi Museum, Guilherme de la Penha's ArchiveMarajó island in 1896: one of Jacques Huber’s photos in the Goeldi Museum’s collectionEmílio Goeldi Museum, Guilherme de la Penha's Archive

The organized collections and academic work, also carried out in Maceió (Alagoas) and Porto Alegre (Rio Grande do Sul), show the progress made. The professionals who specialize in preserving glass negatives are recognized through requests to evaluate or rescue collections that have been neglected for decades at institutions in Rio de Janeiro and other states. But those who handle this type of material suffer the same agony: “Before we established standards and spaces for conservation, a lot of material was lost or broken,” says Lacerda.

The Emílio Goeldi Museum (MPEG), in Belém, houses 1,421 glass negatives produced as early as 1894 and restored with the support of the Brazilian Federal Savings Bank and FUNARTE between 2006 and 2010. “There must have been more than 5,000. Most have been lost due to the carelessness of a few generations,” laments science historian Nelson Sanjad, curator of the museum’s historical documentary collections. Luckily, he adds, Swiss botanist Jacques Huber (1867–1914) safeguarded paper copies of the photos he took when he worked at Goeldi, between 1895 and 1914.

In 2013 and 2014, with the support of the Huber family and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Sanjad went to the State Archive of the Canton of Basel-Stadt, in Switzerland, where the photos were sent, and digitized around a thousand images, which he then brought back. In April, the Federal University of Paraná (UFPA) museum opened an exhibit of Huber’s photos, which had already been exhibited in the city of São Paulo in 2022 and 2023.

Scientific articles

HEIZER, A. Notícias sobre uma expedição: Jean Massart e a missão biológica belga ao Brasil, 1922–1923. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos. vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 849–64. july–sept. 2008.