Graphene has reached a commercial tipping point. Two decades after its first isolation, the carbon-based nanomaterial is now present in a range of consumer goods available locally and in innovations at advanced stages of testing. Although the market remains incipient, importers and some local manufacturers are now offering graphene in Brazil either as a raw material or embedded in solutions for a variety of products, including additives for paints, plastic packaging, and lubricants. Innovation ecosystems are also forming around science and technology institutions, fueling graphene production and new applications. Leading Brazilian companies in the oil, gas, and mining industries are field-testing devices containing graphene to integrate them into their production processes.

The Mackenzie Graphene and Nanotechnology Research Institute (MackGraphe) in São Paulo has become a key local hub for market-oriented graphene research and development. The institute was created in 2013 on Mackenzie Presbyterian University’s São Paulo campus with funding from FAPESP. One of MackGraphe’s founders, physicist Eunezio Antonio Thoroh de Souza, launched a startup of his own in 2018, called DreamTech Nanotechnology, to translate graphene research into real-world applications. He partnered with Chinese multinational DT Nanotech to source commercial graphene (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 284 and 291). Working with local distributor MCassab, DreamTec is introducing graphene and other two-dimensional materials to the Brazilian market. Now, it plans to produce graphene domestically.

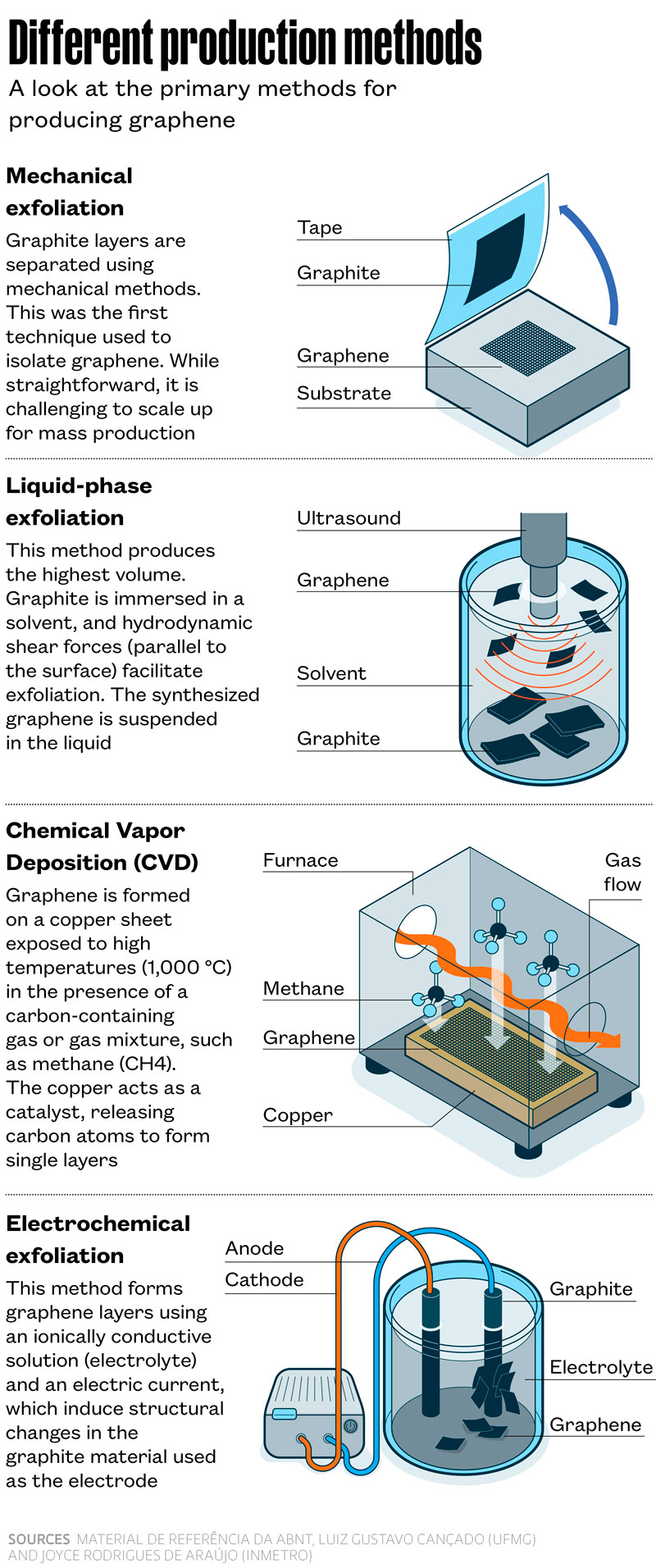

“We are currently setting up a production facility in Araras, São Paulo, with an annual production capacity of 200 metric tons of graphene,” says Thoroh. “Given the projected rise in graphene demand, establishing a local plant makes strategic sense, especially with DT Nanotech executives as co-owners. We expect production to begin by late 2025.” DreamTech plans to use the liquid-phase mechanical exfoliation method and will focus on products such as anticorrosive paints, composites, asphalt coatings, lubricants, and construction materials.

Also in São Paulo, Gerdau Graphene—a startup under Gerdau Next, the new business division of steel producer Gerdau—has already brought seven graphene-based products to market and plans to launch at least three more by year’s end. Established in 2021, the company markets graphene-based additives for polymer films, cementitious matrices, paints, and coatings.

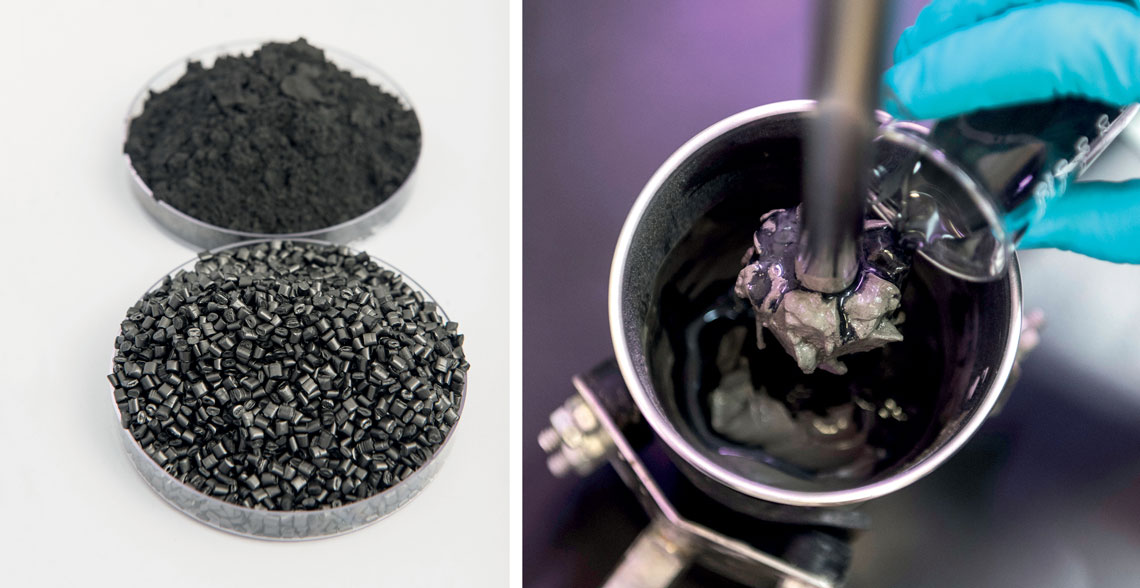

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP | Bárbara CalGraphite exfoliation using adhesive tape (left) and a UFMG researcher handling a graphene solutionLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP | Bárbara Cal

“Graphene is now a commercial reality,” says chemist Valdirene Peressinotto, CEO and Innovation Director at Gerdau Graphene. “It imparts enhanced properties to its host materials, making them stronger and more durable,” she explains. “Our additives are now being manufactured on an industrial scale, in tons or thousands of liters. Graphene is no longer an experimental material confined to the lab.”

A Nobel Prize-winning material

The first theoretical study on graphene’s electrical properties dates back to 1947, but its history in experimental physics is much more recent. It began in 2004 when physicists Andre Geim—now a partner at DreamTech Nanotechnology and DT Nanotech—and Konstantin Novoselov isolated a single sheet of carbon atoms at the University of Manchester. They achieved this by using adhesive tape to exfoliate a specimen of graphite, a mineral mined from natural deposits.

They then placed the ultra-thin, flat layer of atoms on a substrate to make it visible under an optical microscope, built a small device, and measured the electrical and magnetic properties of the two-dimensional material. Although scientists had predicted the existence of graphene decades earlier, they generally believed it would be too unstable to exist as a single-layer crystal. Geim and Novoselov’s groundbreaking work earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010.

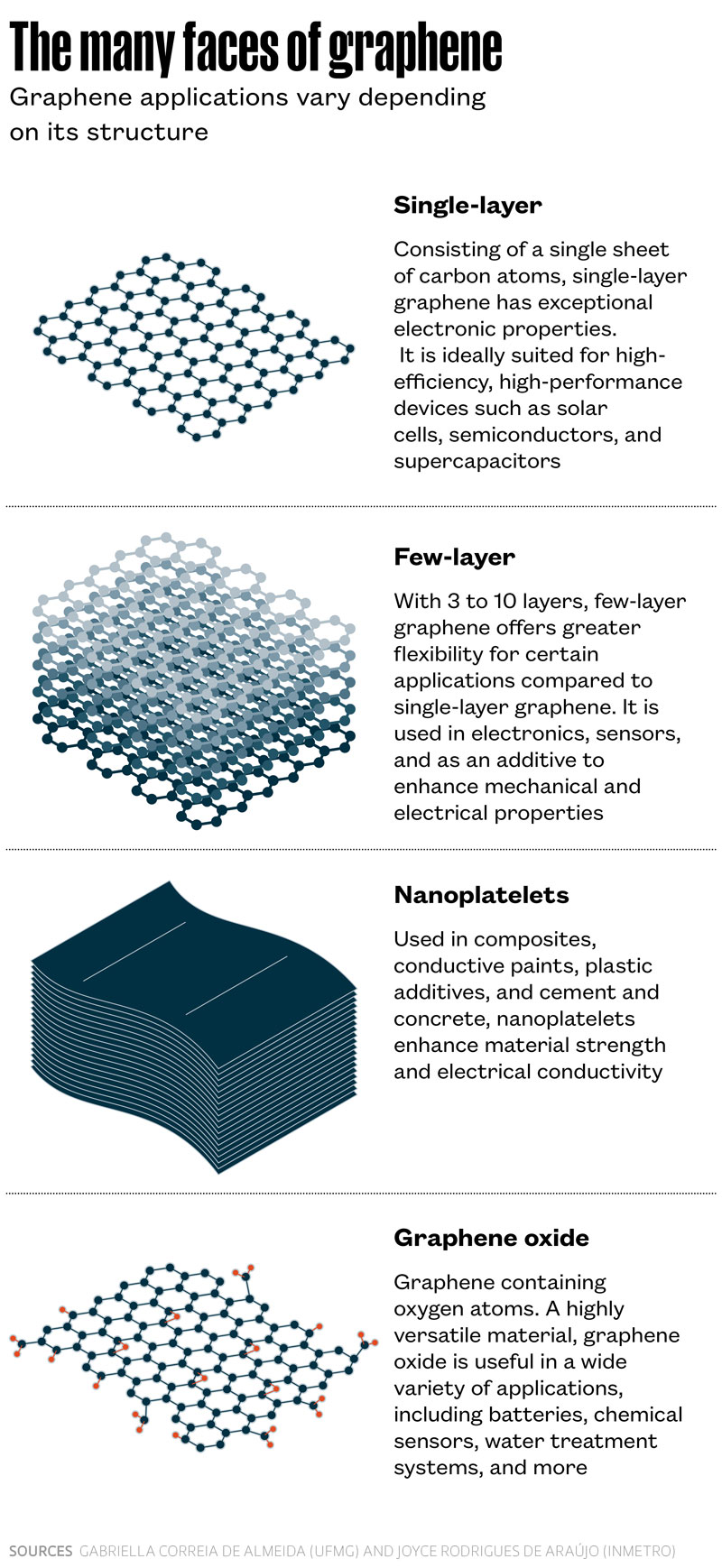

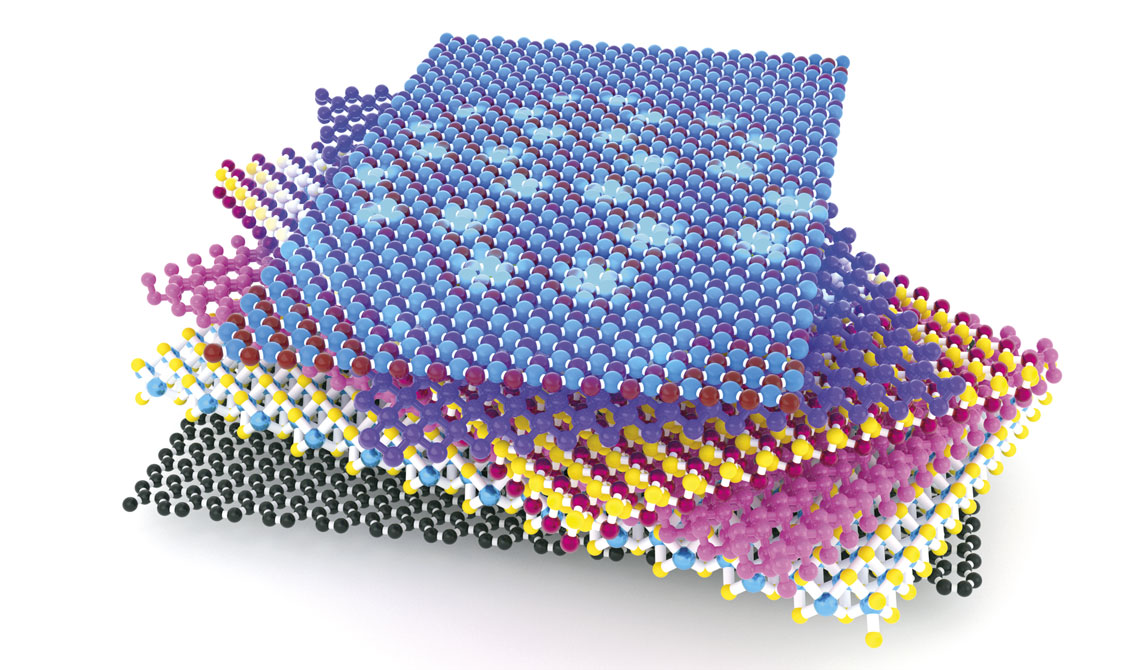

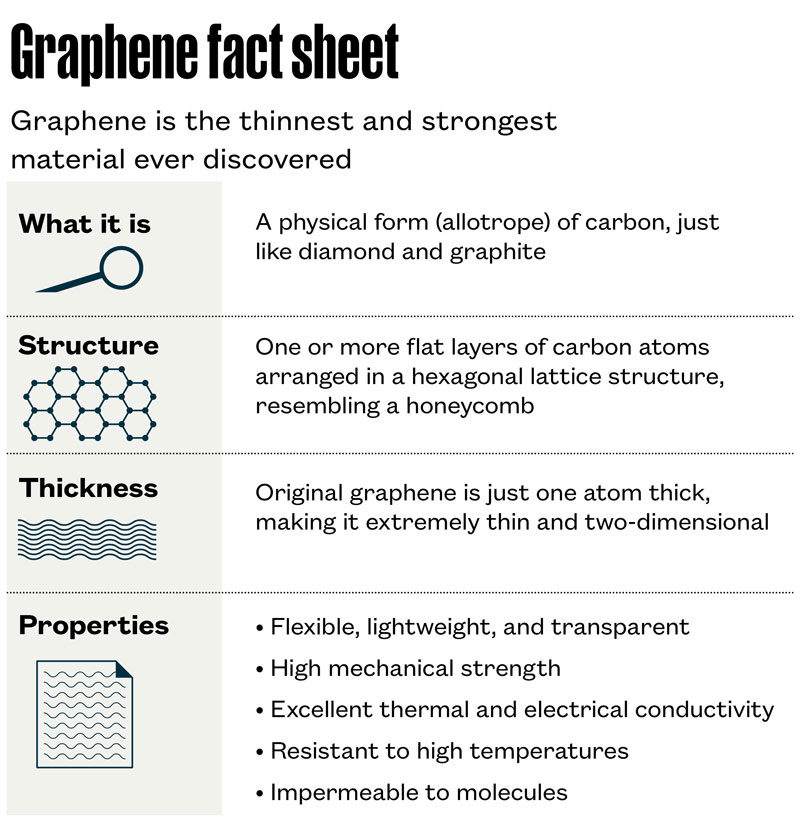

With its atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice—like a honeycomb—all in a single plane, graphene is extremely lightweight, transparent, flexible, and impermeable (see infographic below). It also has exceptional electrical and thermal conductivity and high mechanical strength. Graphene’s distinctive electronic and magnetic properties have led to entirely new areas of physics, such as valleytronics, which studies changes in electron behavior within graphene, and twistronics, which explores the effects of rotating one of the layers in systems made of two or more layers of graphene or other two-dimensional materials.

Graphene has also opened new research avenues in the physics of two-dimensional systems and other atomic-layered materials, such as graphite. Geim and Novoselov’s discovery has thus had a profound impact on fundamental research in materials science.

An expanding market

Graphene and materials derived from it offer unique properties that hold promise for a host of technological applications in different industries. Market consultancy Fortune Business Insights estimates that the global graphene market was valued at US$432.7 million last year. By 2032, it is projected to reach US$5.2 billion—an extraordinary growth in under a decade.

Globally, applications for graphene and its derivatives are expanding rapidly, ranging from electronics manufacturing to composite materials and batteries. The graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) segment led in market share in 2023, according to the Fortune Business Insights report—GNPs are two-dimensional nanomaterials consisting of multiple layers of graphene. The electronics, aerospace, automotive, defense, and energy sectors are among the largest consumers. Regionally, Asia Pacific dominates the graphene market with a share of 34.43%.

“Graphene’s properties make it suitable for a broad range of applications. My research center has already produced six spin-offs, and we have five more in the pipeline,” says Brazilian theoretical physicist Antonio Hélio de Castro Neto, director of the Centre for Advanced 2D Materials and the Graphene Research Center at the National University of Singapore (NUS), one of the world’s leading graphene research hubs—Nobel laureate Konstantin Novoselov is also a researcher at NUS.

Eugênio SávioContainers with different types of graphite and grapheneEugênio Sávio

Among the university’s spin-offs are NanoMolar, which develops medical sensors, and UrbaX, focused on construction materials. Castro Neto, who completed his physics degree at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and has been abroad for over 30 years, notes that NUS now boasts over 200 patents related to graphene and its applications.

Although demand is rising in multiple sectors, graphene has yet to become fully commercial at scale. A recent article by German researchers in 2D Materials found that many graphene manufacturers remain in early commercial stages, facing the dual challenge of building a customer base and securing funding to scale production. There are also niche markets developing under confidentiality agreements, as customers often prefer to keep graphene experiments private to avoid attracting competitors’ attention and to protect their proprietary production formulas.

“The [market’s] relatively small size […] goes along with strong growth in upcoming years with forecasted growth rates ranging between 20% and 50% per annum. […] Graphene cannot immediately convert all its initial promises to overwhelming market success. The diffusion of this novel class of two-dimensional materials takes time,” the authors wrote. The study was part of the Graphene Flagship, a European initiative bringing together 118 industrial and academic partners.

According to Peressinotto, the market is still developing and consolidating, not only in Brazil but globally. Peressinotto has been researching carbon nanomaterials, including graphene, since 2004, when she was a staff researcher at the Nuclear Technology Development Center (CDTN) in Belo Horizonte, working with a team from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESPCement paste being prepared with graphene-containing material; on the left, powdered graphene (in the background) and an additive compound based on a thermoplastic material and grapheneLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

The startup’s first major success was a project on behalf of Gerdau—an industrial trial with the supplier of polymer films used to package nails. “We successfully reduced packaging thickness by 25%, increased puncture and tear resistance by 30%, and reduced process losses by more than 40%,” says Peressinotto. By incorporating the additive into the nail packaging line, Gerdau saved roughly 72 metric tons of plastic over one year.

Gerdau Graphene, which develops its products in collaboration with the Graphene Engineering Innovation Center (GEIC) at the University of Manchester, sources its graphene from producers in Brazil, Canada, the United States, England, Spain, Australia, and other countries. Importing is necessary, Peressinotto explains, because Brazil currently lacks suppliers with the capabilities to produce graphene in the formats, quantities, and at the competitive prices the company requires.

In Brazil, graphene is mainly used in applications that exploit its mechanical properties. “The primary uses for graphene in Brazil are still in paints, elastomers [polymers with elastic properties], composites, packaging, and cement. These applications are linked to heavier materials, such as those in the construction and automotive sectors,” says Luiz Gustavo Cançado, a physicist at UFMG. After previously heading the MGgrafeno Project in 2016, Cançado and his team developed a pilot process for large-scale production of graphene and tested over 20 applications for the material.

“Graphene is incredibly strong. It takes a great deal of force to break it. When blended into polymers, rubber, cement, or ceramics, it enhances the overall mechanical properties of the resulting material,” says Marcos Pimenta, also a physics professor at UFMG. “But developing and producing these materials is no easy task.”

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESPA Gerdau Graphene laboratory created to develop graphene-based solutions for constructionLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

A pioneer in carbon nanomaterials research in Brazil, Pimenta founded and directed UFMG’s Center for Nanomaterials and Graphene Technology (CTNano) for 10 years, where today, in a 3,000-square-meter facility, around 100 researchers work across 10 laboratories to develop custom solutions and technologies. “At first, our projects were primarily for two companies. Today, we have several initiatives in the pipeline for companies from different industries,” he explains.

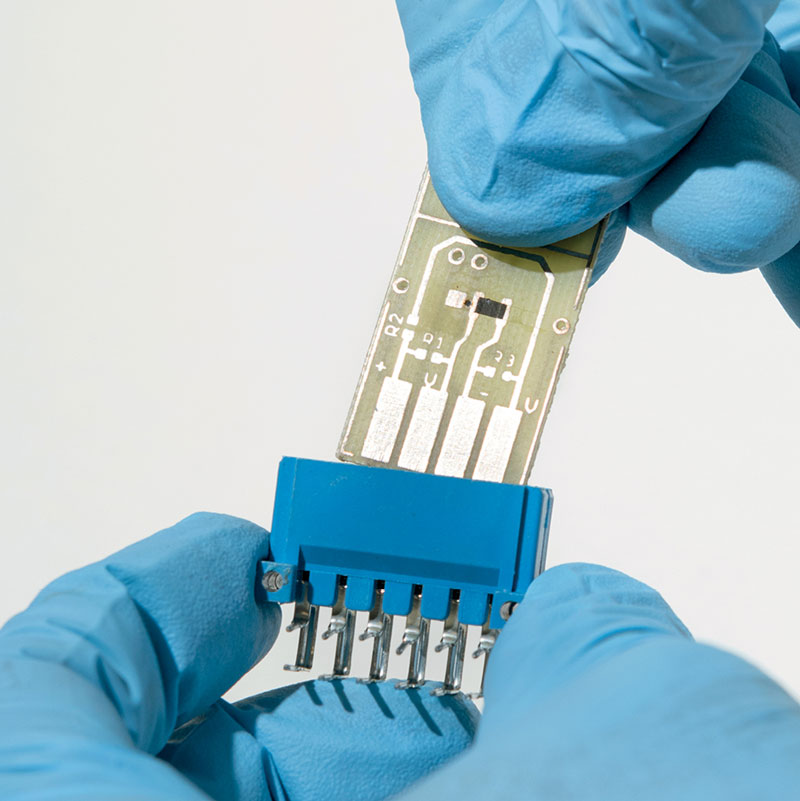

According to physicist Rodrigo Gribel Lacerda, current general coordinator at CTNano, now a unit within the Brazilian Agency for Industrial Research and Innovation (EMBRAPII), the center has partnered with 15 companies to date. Among its most advanced projects is a nanosensor made with carbon nanotubes (layers of graphene rolled into a cylinder) to monitor carbon dioxide levels in natural gas extracted from Brazil’s offshore pre-salt oil reserves.

“We are currently bench-testing the device, developed in collaboration with Brazilian oil giant Petrobras. The remaining step is real-world testing before commercial launch,” says Lacerda. Another project at the same development stage is developing a strain sensor for mining machinery. A third project is using graphene to make water filters.

One of Brazil’s first graphene production facilities, UCSGraphene, in Caxias do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, was developed by the University of Caxias do Sul (UCS) and has been operational since March 2020. Affiliated with EMBRAPII, UCSGraphene uses liquid-phase exfoliation to develop and produce graphene and other carbon-rich materials, with a production capacity exceeding one metric ton per year.

Bárbara CalA chip with a gas-detecting graphene nanosensor developed at UFMGBárbara Cal

“Besides making graphene from graphite and other carbon sources, we are creating a range of solutions that incorporate graphene and its derivatives, as well as production routes for other carbon-based nanostructures like graphene oxide and modified graphenes,” says UCSGraphene Coordinator Diego Piazza, a materials engineer. Piazza, who also teaches at UCS, has collaborated with various companies and science and technology institutes on graphene research projects.

“Our team’s technological developments and research into graphene and its derivatives include applications in composite materials [polymers, ceramics, and metals], protective equipment, lubricants, paints and coatings, filtration systems, regenerative medicine, and technical components,” he says. “Several of our solutions are already being marketed across sectors such as fashion, mobility, and logistics.”

In Belo Horizonte, another facility with industrial production capabilities is preparing to bring its technologies to market. Co-located at CDTN, the plant was built as part of UFMG’s MGgrafeno Program in collaboration with the state-owned Minas Gerais Development Company (CODEMGE), with a capacity of about one metric ton of graphene per year. “We plan to transfer the technology we develop in this project to parties looking to produce graphene for commercial and industrial applications,” says Cançado from UFMG. The plan is for private partners to utilize CDTN’s facilities for development.

UFMG and CDTN co-own the intellectual property generated as part of the project, including the liquid-phase exfoliation method for producing graphene from graphite. Cançado explains that a major challenge in scaling up commercial applications for graphene lies in achieving reproducible large-scale production.

NanoMolarA biosensor made with graphene for glucose testing, created by NanoMolarNanoMolar

Another hurdle is establishing standards for production, quality control, and material safety. Finally, having reliable information to confirm the material’s authenticity as graphene—and not another allotrope of carbon, like graphite—is crucial. Allotropes are simple substances made of the same chemical element, differing in the number of atoms or their crystalline structure.

The Brazilian National Institute of Metrology, Quality, and Technology (INMETRO) recognizes the need for quality control of graphene sold in Brazil, whether domestically produced or imported. Since last year, the institute has been working to develop a graphene certification mark and program, informally called the Graphene PAC (Growth Acceleration Program). Both are set to launch around mid-2025.

“When graphene transitioned from the lab to commercial production, INMETRO saw the need to develop measurement methods [to verify the number of graphene layers and the purity of graphene contained in products] and create a reference standard to guide conformity testing of the material. In collaboration with ABNT [the Brazilian Standardization Organization], we developed standards on identifying and classifying this nanomaterial,” says chemist Joyce Rodrigues de Araújo, head of the Laboratory for Surface Physics and Thin Films (LAFES) at INMETRO’s Division of Materials and Surface Metrology. In 2024, she was awarded 3M’s “25 Women in Science” prize for her work developing bio-graphene, created from processing biomass such as rice husks and sugarcane bagasse.

Araújo notes that commercial graphene products rarely contain single-layer graphene like that produced at the University of Manchester in 2004. “Graphene is a family of compounds that vary by the number of layers and physical form,” she explains. It includes original single-layer graphene, multi-layer graphene, and graphene nanoplatelets (see infographic).