Fiscal incentives created to encourage Brazilian industry to adopt low-carbon technologies could be a magic bullet for restructuring the manufacturing sector, and boost its performance over the next decade. “If coordinated well, policies of this type would allow Brazil to continue developing while at the same time complying with its Paris climate agreement commitments,” says economist Camila Gramkow of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) in Brasília. She is one of the authors of a study published in late 2019 that used economic models to identify technologies and fiscal mechanisms capable of reducing Brazilian industry’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions without compromising the country’s growth over the next decade.

Gramkow began her analyses during her doctoral studies at the University of East Anglia, in England. Based on data from the World Bank, she and her advisor, Estonian economist Annela Anger-Kraavi, selected six low-carbon technologies that if adopted by Brazilian industry could mitigate CO2 emissions, for example by improving energy efficiency and encouraging materials recycling (see table). “Each of them has a high degree of technological maturity and is available to be incorporated by industry over the coming years,” she explains. They then assessed whether the introduction of fiscal instruments to encourage the adoption of these technologies by industries would be consistent with a virtuous development cycle in Brazil.

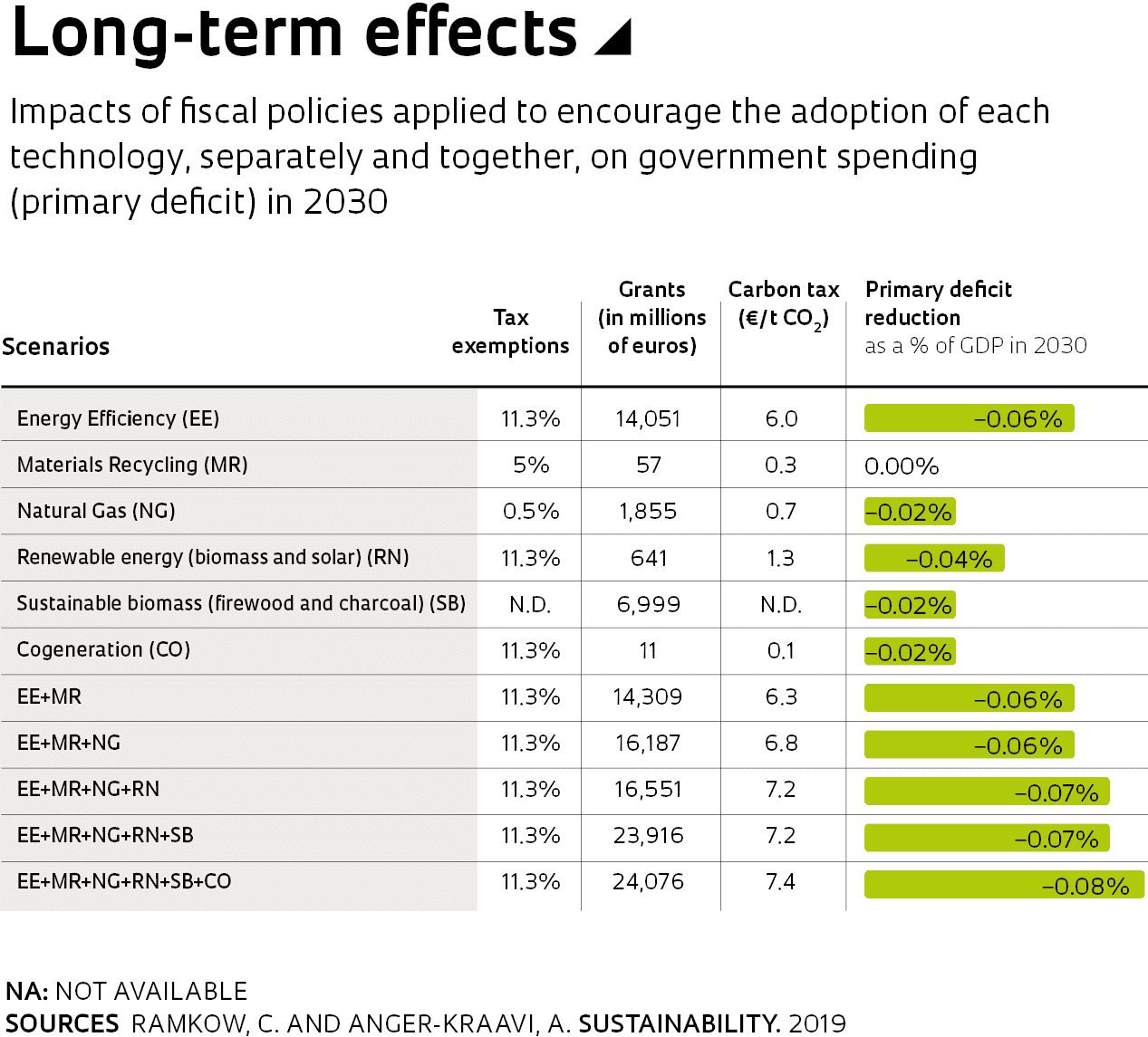

The economists projected the results annually through 2030 based on 11 fiscal stimulus scenarios, implemented with the goal of directing investments towards the adoption of each technology, separately and together. One of the incentives would involve reducing corporate taxes by up to 11.3%, from the current 24.3% down to 13% for companies that invest in adopting green technologies. Another strategy the researchers considered concerned providing publicly funded grants so that companies would incorporate low-carbon technologies into their production structure. This could be done through agencies such as the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES). “While tax relief would reduce the cost of investment in green technologies, public funding would lower the costs and risks associated with their adoption,” Gramkow observes.

BNDES offers a line of funding for capital assets that currently may be used by companies to acquire low-carbon technologies. The problem, according to the economist, is that this line of funding is repayable, meaning that companies need to repay the amount borrowed, with interest. “This makes this mechanism unattractive to companies, since the adoption of green technologies involves risks and costs that, when added to the interest they would have to pay the BNDES, would make incorporating them unfeasible,” he explains. In order to function according to the scenarios projected in the study, this line of financing would have to be adapted taking sustainability criteria into account.

Carbon tax

To compensate for the loss of revenue and additional public spending associated with providing public funds to companies, the researchers propose creating a tax on CO2 emissions similar to that adopted in many nations around the world, including in Latin American countries such as Chile, Colombia, and Mexico. In Brazil, the tax would apply to emissions from fossil-fuel combustion in every sector of the economy (except for households), with a rate that would be proportional to the incentives offered in each scenario simulated in the study. This tax could work similarly to the current Contribution for Intervention in the Economic Domain (CIDE) levy, but with a focus on CO2 emissions, and not on fuel consumption. “The carbon tax and green fiscal incentives would encourage industries to emit less carbon competitively while at the same time encouraging them to invest more in the adoption or development of new green technologies. From the government’s point of view, this would be a way to offset the budgetary impacts associated with implementing the fiscal incentives,” she explains. In one of Gramkow’s simulations, the new tax would be as high as €6 per ton of CO2 emitted, in order to offset the reduction in corporate taxes from 24.3% down to 13%, and require investing almost €14 billion to encourage the adoption of technologies that would promote increased energy efficiency in industrial processes by 2030 (see table).

The authors acknowledge that the adoption of a carbon tax would affect society at every level, especially the poorest populations, who could end up paying more for the products and services that make up their market basket. To correct this socioeconomic distortion some items consumed by families, such as cooking gas, would not be taxed. At the same time, government would recompense society the amount collected by the tax in the form of public policies that would alleviate the tax’s impact through increased income and wages. “The revenues would help to guarantee the health of public coffers, and finance R&D on new green technologies at companies and universities, or they could be applied to reduce social inequality, either by reducing labor taxes to stimulate job creation, or by raising the minimum wage,” she adds. In her assessment, these strategies would pave the way for a more sustainable development cycle in Brazil, with an annual increase in investments of up to 1.16% and an improvement in the trade balance of 2.5% by 2030.

To implement these strategies, the country could take advantage of existing fiscal instruments and build on successful policies government has implemented over recent years. The tax benefits associated with the sales and services tax (ICMS) have been used as tools in several states to promote the improvement of manufacturing processes and the adoption of green technologies in industry. In 2003 alone, 11 states and the Federal District agreed to grant ICMS exemptions to companies in the plastics and packaging industry that reuse bottles made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in manufacturing adhesives. The strategy increased the recycling rate of PET bottles, which would otherwise contaminate the environment, and promoted income generation, since most of the reused bottles were collected by waste picker’s cooperatives. Other states are working individually to encourage the adoption of more sustainable processes in industry through ICMS exemption mechanisms. Since 1997 the state of Ceará has allowed companies that manufacture products made from recycled materials to reduce their tax rate from 17% to 7%.

Change of profile

These initiatives, though modest, point to a possible path for the industrial sector. “This is a path of no return,” emphasizes economist José Luis Gordon, director of Planning and Management at the Brazilian Agency for Industrial Research and Innovation (EMBRAPII). “Companies around the world are increasingly concerned with finding new technologies that will enable them to achieve economic growth while reducing carbon emissions.” He believes this trend results from companies’ concerns for maintaining their ability to compete amidst strong pressure from rivals in numerous other countries.

The tax strategies evaluated in the study could have a positive impact even during the current climate of economic slowdown and diminished industrial activity, according to the study. This is because the fiscal stimulus policies, if adopted, would reduce companies’ costs both for investing in green technologies, and the risks associated with their adoption. “These policies are even more important given the country’s current economic situation,” says Gramkow. In her view, the deindustrialization of the Brazilian economy has contributed to the country losing ground in the global consumer goods market, becoming more dependent on exporting commodities, and susceptible to their global price fluctuations. “Brazil is losing market share within global value chains and that could have long-term consequences,” she adds. Implementing fiscal policies that encourage the adoption of green technologies could be important not only because it would favor the implementation of a broader environmental policy, but also because it would help Brazilian industry to enter markets with stricter environmental requirements.

Fiscal incentives would pave the way for a more sustainable development cycle in Brazil

Gordon further emphasizes that the business sector has sought to adopt this type of technology in order to increase its productivity and become competitive in global markets. “At EMBRAPII we have supported many projects aimed at developing new green technologies. This indicates that there’s already a demand in the sector for this type of innovation; it’s now up to the government to propose mechanisms that encourage this practice in a more widespread way,” he points out.

Investment in R&D

Economist André Rauen, from the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA), emphasizes that the strategy proposed in the study would need to be accompanied by policies that also encourage Brazilian manufacturing to develop green technologies. “The researchers demonstrate that the tax exemption policies provide stimulus for industries to implement green technologies into their production chains, but it’s important that the companies invest internally in R&D,” the economist stresses.

Rauen states that few companies allocate their resources to projects that involve technological risk, even when receiving tax incentives. “Instead of increasing investments in R&D, they use the tax relief to continue incremental research, which has low levels of innovation.” Another problem is that a significant part of the tax incentives are being used by companies to finance development rather than research activities, which is out of alignment with the goal of tax exemptions that are supposed to encourage companies to increase investment in advanced research.

In Rauen’s view, Brazil needs to find a point of equilibrium within the set of fiscal instruments used to finance green innovation in industry. “This portfolio should include tools for direct and indirect support for commercial research, such as tax exemptions, and strategies to encourage the creation of new public requirements, through guidelines on public tenders for government contracts and regulation of private markets,” he suggests.

These strategies have been applied for some time by countries in Europe and in some American states. “The idea is to create requirements through public spending that promote more energy-efficient products, or to define stricter environmental certification standards,” he explains. “California has done this with respect to the automobile sector, demanding better energy efficiency from electric cars produced in the state. In the UK, buildings receive energy efficiency certification seals, which leads the construction sector to invest in the associated new technologies.”

Rauen believes these policies need to be structured horizontally, so that they can be used by companies in different segments. This would encourage the development of low-carbon technologies on a broad scale. “Vertical policies, like the IT Law, target incentives only toward specific sectors. The horizontal model, on the other hand, has been used by many countries to encourage technological innovation, promoting interaction between companies and research centers.”

Scientific article

GRAMKOW, C. and ANGER-KRAAVI, A. Developing green: A case for the Brazilian manufacturing industry. Sustainability. Vol. 6783, no. 11, pp. 1-16. Nov. 2019