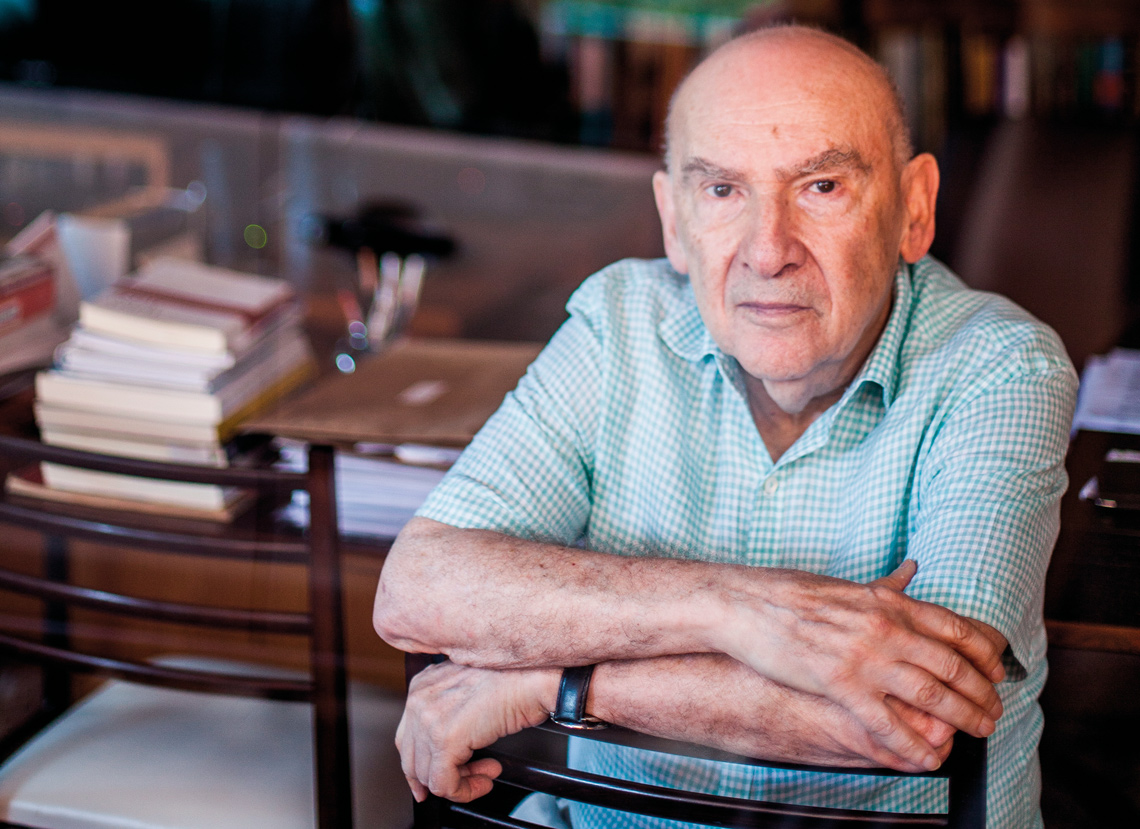

Raquel Cunha / FolhapressFausto at his home in the Butantã neighborhood of São Paulo in December 2014, during the launch of his book O brilho do bronzeRaquel Cunha / Folhapress

When thinking back to the last time she spoke with historian Boris Fausto, who died on April 18 aged 92, political scientist Lourdes Sola recalls that their conversation revolved around their respective “solo careers.” Despite both working at the Department of Political Science of the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (DCP-FFLCH-USP), their trajectories were influenced by coups d’état, family circumstances, and research interests.

Fausto titled one of his autobiographical books Memórias de um historiador de domingo (Memoirs of a Sunday historian; Companhia das Letras, 2010). The title reflects his self-deprecating sense of humor, but it is also technically the truth. In the first few decades of his academic career, he carried out research at the same time as holding a professional career as a lawyer, a legal consultant for USP, and a state attorney. Born in 1930, he graduated from USP’s School of Law in 1953. Ten years later, he enrolled on the university’s graduate history program, encouraged by his wife, the educator Cynira Stocco Fausto (1931–2010). He completed the course in 1966 and then completed his PhD in 1969, supervised by Sérgio Buarque de Holanda (1902–1982).

Fausto said that his atypical career was a source of both limitations and freedom. Since he was unable leave his post at USP for long periods, he decided to focus his research on themes related to the city of São Paulo and historiography. At the same time, because he was not immersed on a daily basis in academia, which was beginning to become a more professional vocation at that time, he was able to choose research topics, methods, and writing styles that were more in line with his tastes.

“Without taking into account his high degree of intellectual autonomy and independence, it is impossible to define Boris,” declares Sola. “There is no formula for achieving this level of autonomy. It is simply a characteristic of someone motivated by impulse, curiosity, solid intellectual training, and excellent writing. Boris was atypical in the field of history and he was atypical in political science.”

This characteristic was evident in his first book, the result of his doctoral thesis: A revolução de 1930: História e historiografia (The revolution of 1930: History and historiography; Brasiliense, 1970). His stated intention of the work was to critique the hegemonic interpretation of the time, formulated by historian Nelson Werneck Sodré (1911–1999), who saw the uprising that brought Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954) to power as a moment of triumph for the national bourgeoisie, in conflict with agrarian elites, who were more regressive.

In the article “The Estado Novo and the debate on populism in Brazil,” historian Ângela de Castro Gomes of the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), states that the book was “the first major historiographical contribution to studies of the 1930 revolution” and decisively influenced the understanding of this historical event.

Fausto’s work is characterized by an interface with the social sciences—in the thesis for his teaching postdoctorate at DCP, for example, which he completed in 1975: Trabalho urbano e conflito social, 1890–1920 (Urban work and social conflict; Difel). The thesis addresses the formation of the working class and the labor movement in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro during the First Brazilian Republic. Fausto was motivated by his connection with political scientist Francisco Weffort (1937–2021) at the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP), where both men worked since 1971. At the invitation of his advisor, Sérgio Buarque de Holanda, he organized the four volumes on republican Brazil in the collection História geral da civilização brasileira (General history of Brazilian civilization; Difel, 1980).

Sola cites two later books as representative of the multidisciplinary nature of Fausto’s work: História do Brasil (History of Brazil; Edusp, 1994) and Argentina-Brasil 1850–2002: Um ensaio de história comparada (Argentina-Brazil 1850–2022: A comparative history essay; Editora 34, 2004), the latter written in partnership with Argentine historian Fernando Devoto. “His focus was mainly political history, but it was more multidisciplinary than one might expect. He was aware of the economic dimensions of Brazil’s historical problems, something that historians and political scientists often ignore,” he notes.

Although he continued to study the First Republic, he began looking at a new topic in the 1980s and 1990s: criminality, which allowed him to explore urban sociology and the issue of immigration, in which he had great interest. The first result was Crime e cotidiano: A criminalidade em São Paulo, 1880–1924 (Crime and everyday life: Crime in São Paulo, 1880–1924; Brasiliense, 1984), which examines the social relations that surrounded crime, in addition to the role of social control exercised through repression. He returned to the theme in later works, such as O crime do restaurante chinês (The Chinese restaurant crime; Companhia das Letras, 2009), based on a murder that took place in São Paulo in 1938 that caught his attention when he read about the case in the newspapers as a child.

In these books, the historian uses less technical language, and many readers considered them more like literature. The inspiration is microhistory, a trend that originated in Italy in the 1970s and uses episodic events, often news from the press, to create a picture of a historical period.

Born in São Paulo in the same year as the revolution that he would go on to study, the historian was the son of Jewish immigrants and said that his taste for knowledge came from his Jewish heritage and his interest in history, having grown up reading newspapers to his blind grandfather. At school, he was a student of historian Emilia Viotti da Costa (1928–2017), who strengthened his interest in the discipline and later became his friend and university professor.

Sola attributes Fausto’s sense of humor, fondness for memoires, and interest in the topic of immigration to this family background. The book Negócios e ócios: Histórias da imigração (Business and leisure: stories of immigration; Companhia das Letras, 1997) is both autobiographical and an essay on the life of foreigners in São Paulo. His last semiautobiographical book was released about two years ago: Vida, morte e outros detalhes (Life, death, and other details; Companhia das Letras). In the final years of his life, he lived with the consequences of a stroke he had in 2021.

Luiz Henrique Lopes dos Santos, a FFLCH-USP researcher who specializes in the philosophy of logic and the history of philosophy and assistant coordinator of FAPESP’s Scientific Board, believes that as coordinator of human sciences and humanities at FAPESP in the late 1980s, Fausto played a key role in consolidating the fields at the foundation.

Republish