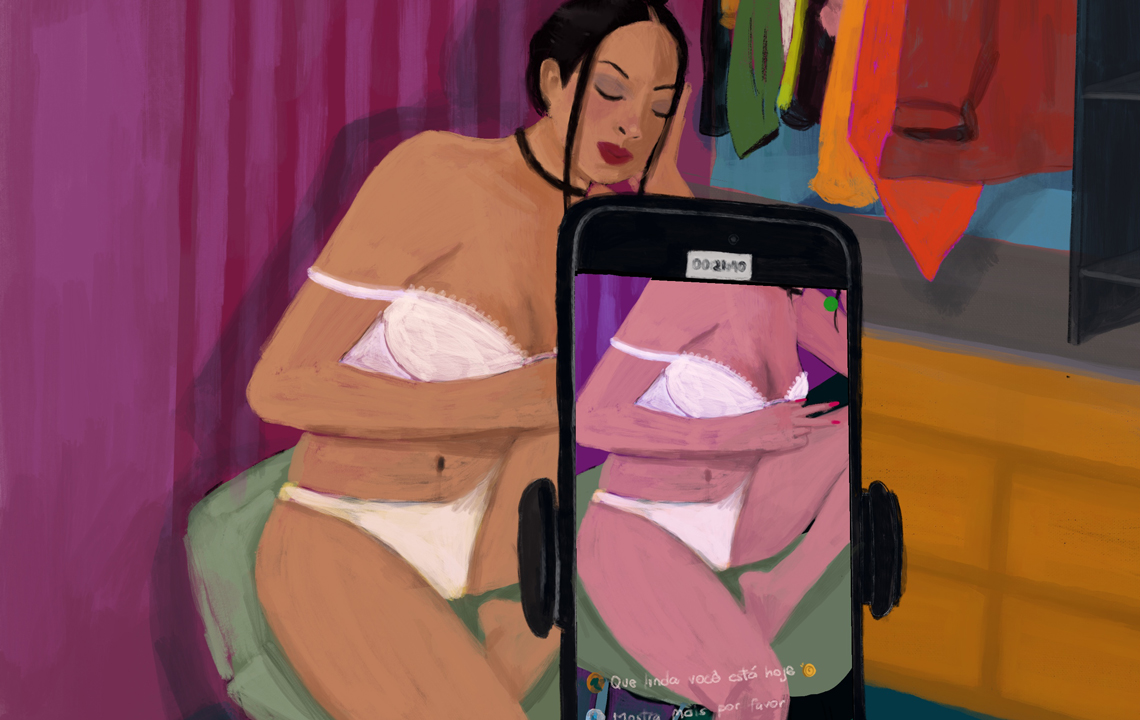

Angélica (a fictional name) created her profile on a digital platform for escorts in order to attract new clients, work with more autonomy, and increase her income. Since then, almost every day, she does her makeup in the bathroom at home, puts on a revealing outfit, and seeks the best angle to position the camera installed in the lounge of her apartment, from where she broadcasts videos and takes erotic photos.

The story of this woman, which is part of sociologist Cristiane Vilma de Melo’s PhD research, defended at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar) in 2024, illustrates how the digital era broadens the scope of work for professionals in the sex industry. The term sex industry refers to the economic and social relationships involving sexuality, including the commodification of the body for financial gain.

Live broadcasts, subscription-based content, and the sale of erotic services online are some of the new offerings made possible by the emergence of adult content platforms such as OnlyFans and Câmera Privê. There are sex workers who incorporate these types of services as an additional source of income and as a way to promote their in-person work. Others only work on online platforms. This group coexists with people who continue to work in street prostitution in neighborhoods such as Luz, in downtown São Paulo, and Vila Mimosa, in Rio de Janeiro.

However, in a virtual realm of apparent freedom, contradictions also exist. In Brazil, sex work is not prohibited, but it is not regulated either. Therefore, digital platforms are free to determine the fees they charge, the performances allowed, and how the professionals, most of whom are women, are paid for producing this type of content.

In her PhD research, Melo analyzed the offer of erotic services in digital environments. According to the study funded by FAPESP, new technologies have driven changes in the meaning that professionals attribute to their work. “They have begun creating narratives that give new meaning to sex work as a conscious choice and an experience of autonomy,” says the researcher. Melo emphasizes that these narratives serve a dual purpose: they act as marketing strategies while also serving as tools that help confer legitimacy to a profession historically tainted by stigma.

In the study, Melo interviewed 31 women who were working or had worked on the platforms OnlyFans and Câmera Privê, as well as on regular social media platforms such as Instagram and Twitter, which they used to promote their services. According to the sociologist, the majority of the 31 women interviewed were already sex workers before entering the digital world. They began signing up for online platforms from 2020 onward, during the COVID-19 pandemic. While some of those interviewed chose to work exclusively with erotic services on digital platforms, others began using this exposure to attract clients for in-person meetings. “With the platforms, many of these women began having more control over the dynamics of their meetings,” she says.

Also interested in understanding the role of digital platforms in Brazilian sex markets, researcher Lorena Caminhas of Maynooth University in Ireland has been studying this scenario since 2016. For her social sciences PhD, defended at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), she analyzed erotic live streams, that is, live broadcasts of sexual content, known as webcamming. In 2010, Câmera Hot was launched, the first platform of its kind in Brazil, followed by Câmera Privê in 2013.

Platforms give more visibility to young, White women

For the researcher, the stigma attached to webcamming is different from the stigma that surrounds street prostitution. “Technological mediation creates a symbolic separation between bodies, which influences both social perception and the way that sex workers see themselves,” suggests Caminhas in an article published this year. She reports that, on webcamming platforms, people’s visibility depends on an automated system. “The professionals appear in rows, from top to bottom, and those at the top have a greater chance of being seen and hired. This logic is controlled by algorithms, the operating criteria of which are not disclosed,” she explains.

Throughout the study, Caminhas interviewed 15 professionals, aged between the ages of 20 and 30, including 13 White women and two Black women. Eleven of them were novices in the sex industry and, within this group, most had left the service sector, with some also working as tattoo artists. The others had prior experiences as actresses in pornographic films or as call girls. Entry into the digital realm was a strategy to compensate for financial losses incurred during the pandemic.

In the study, the researcher identified the existence of gender, racial, and bodily stratification. “Women whose gender identity corresponds to the sex assigned at birth, and who are also young and White, are the ones who frequently appear at the top of the page,” she observes.

According to Caminhas, this logic repeats on other platforms, such as OnlyFans and Privacy, which were the subject of her postdoctoral research, completed in February this year at the University of São Paulo (USP), with funding from FAPESP. Unlike webcamming, where spectators are charged by the minute, these systems operate on a subscription model. This allows the client to pay a monthly fee to access all the content posted on a specific account, including photos and videos.

Caminhas highlights that this form of sex work automation represents a change compared to street-based prostitution. “The professionals publish content in a programmed manner, automate messages, and schedule posts. Some organize an entire month of posts in a single week,” she adds.

As Melo did in her PhD research, Caminhas found that although these professionals work in the sex industry, many do not identify as sex workers. A sex worker is defined as someone who provides sexual services, which can include prostitution or erotic performances, in exchange for money. “Despite offering the same type of service, some women identify as digital strippers or sex workers, while others self-identify as influencers or content creators,” she notes. “The culture of content creators and influencers has encroached into the realm of sex, blurring the boundaries between offering sexual services and erotic digital performance.”

According to both researchers, digital platforms establish contracts with the professionals that include the collection of sensitive data, such as document numbers, location, payment history, likes, comments, and even metadata from posts. “Even after closing an account, this information can be retained by the platform for up to six months,” states Caminhas.

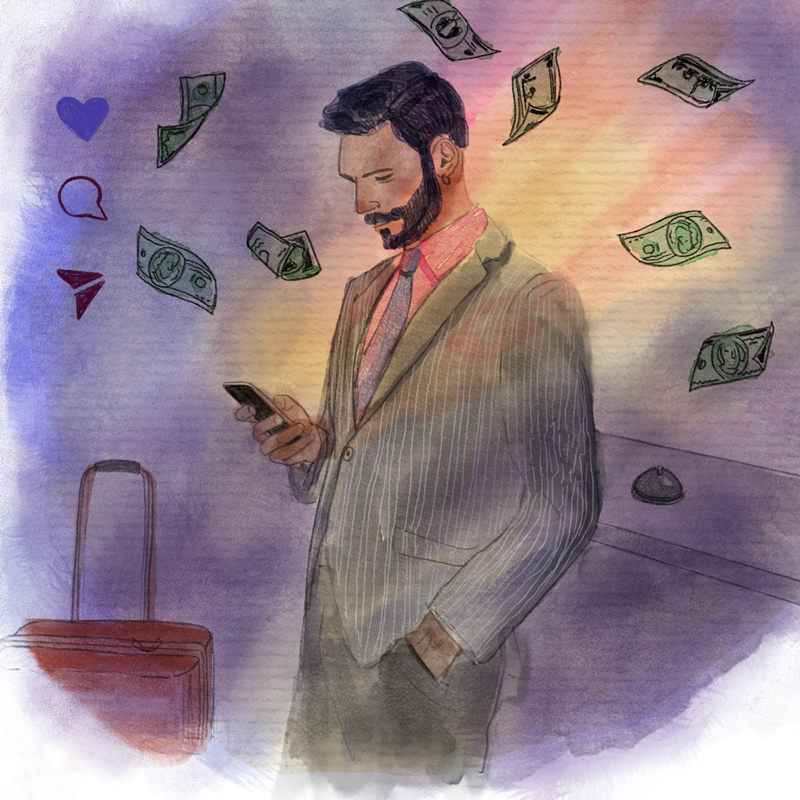

Valentina FraizThe channels also determine how and when the services provided will be paid to the workers. In the case of OnlyFans, considered the largest adult content platform worldwide, payments are processed using foreign money transfer systems, such as Wise, which charge conversion fees, reducing the final amount received. “Although far from ideal, these channels have, in their own way, created a private regulation model for digital sex work, something that the Brazilian state has never proposed,” the researcher criticizes.

Valentina FraizThe channels also determine how and when the services provided will be paid to the workers. In the case of OnlyFans, considered the largest adult content platform worldwide, payments are processed using foreign money transfer systems, such as Wise, which charge conversion fees, reducing the final amount received. “Although far from ideal, these channels have, in their own way, created a private regulation model for digital sex work, something that the Brazilian state has never proposed,” the researcher criticizes.

According to Caminhas, the average monthly income of erotic content creators for subscription services, as reported in the research, ranges between R$5,000 and R$7,000, with some cases surpassing R$10,000. “But it requires intense dedication, between 12 and 16 hours a day, especially to manage social media,” she explains. “Those who stand out in the virtual environment create teams to carry out this work.” According to the research, most of the professionals that work with this type of service belong to higher social classes, while webcamming is more common among individuals from lower-income backgrounds.

As part of her PhD, Melo conducted fieldwork in the Netherlands, where sex work is regulated and civil organizations advocate for the rights of these professionals. In comparing the Brazilian and Dutch scenarios, the sociologist found that, in Brazil, workers disclose their identity and daily routines on erotic platforms and social media to promote their services. In contrast, in the Netherlands, organizations recommend that professionals do the exact opposite, that is, to avoid sharing personal information and to remain anonymous. In the European country, platforms offer more secure payment methods, such as PayPal, and some provide internal reporting systems for abusive experiences, as well as legal assistance when necessary.

Anthropologist Adriana Piscitelli, from the Pagu Gender Studies Center at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), recognizes that sex work offered through digital platforms represents a new arrangement within the erotic market, expanding its possibilities. However, the virtual option has not replaced in-person services. “Women who sell services through digital channels do not necessarily cater to the same clients as those working with in-person prostitution,” she says.

Regarding the profile of clients who seek in-person services, researcher Natânia Lopes clarifies that, in general, wealthy clients do not frequent cheap brothels. During her PhD in anthropology, completed at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) in 2016, she studied the sex industry in the city of Rio de Janeiro, including activities carried out on the streets, in brothels, and on websites offering sexual services, such as Rio Sexy and Barra Vips. “These spaces are part of a hierarchical world. In luxury brothels, for example, services start at R$400, while in regions known for street prostitution, such as Vila Mimosa in Rio de Janeiro, prices range from R$30 to R$50,” she informs.

Street prostitution in Parque da Luz, in downtown São Paulo, is the focus of anthropologist Ana Carolina Braga Azevedo’s research, who is doing a PhD with funding from FAPESP. According to her, factors such as functional illiteracy, difficulty producing audiovisual material, and the requirement to pay fees create barriers for professionals from the region to offer services through digital platforms. “Additionally, the dominant profile on these platforms does not reflect the diversity of body types and ages among the workers from Luz, as some of them are between 60 and 70 years old,” she says.

Inspired by the book O negócio do michê – Prostituição viril em São Paulo (The male prostitution business – Virile prostitution in São Paulo; Fundação Perseu Abramo, 1987), by Argentine anthropologist and poet Néstor Perlongher (1949–1992), fellow anthropologist Guilherme Rodrigues Passamani, from the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), has been researching Brazilian male sex workers for the past nine years. The focus of his analysis is on those who temporarily migrate to Europe to work in prostitution.

Valentina FraizThe anthropologist is currently researching the male prostitution scene in Portugal, which includes the internet, saunas, night clubs, and the streets. Of the 30 Brazilian interlocutors, over 25 hold a university degree. “They are professionals with a high cultural level, who, besides sex, offer services such as companionship at dinners and corporate parties, among other events,” he says. One of the interviewees, for example, is a pianist. Another, who splits his time between Brussels and Luxembourg, has specialized in servicing diplomats of different nationalities.

Valentina FraizThe anthropologist is currently researching the male prostitution scene in Portugal, which includes the internet, saunas, night clubs, and the streets. Of the 30 Brazilian interlocutors, over 25 hold a university degree. “They are professionals with a high cultural level, who, besides sex, offer services such as companionship at dinners and corporate parties, among other events,” he says. One of the interviewees, for example, is a pianist. Another, who splits his time between Brussels and Luxembourg, has specialized in servicing diplomats of different nationalities.

One aspect that caught the researcher’s attention was the prevalence of chemsex, the practice of sexual relations under the effects of drugs such as methamphetamine, as well as Viagra. “These substances enhance the duration of the encounters, making the sessions last for hours or even days,” says the researcher. “Chemsex allows sex workers to significantly boost their earnings. Over a thousand euros can be made in a single night.

However, most of those interviewed by the researcher do not plan to remain in Europe. “These men usually enter the European market via Portugal and later they move on to countries with greater purchasing power, such as Belgium,” he reports. “Some return to Brazil having found success and invest their money in areas such as gastronomy, fashion, and tourism. But others return in poor health, with drug addiction, or without money.”

Sex work in Europe also caught the attention of Piscitelli, from UNICAMP. In the 2000s, she conducted research in Spain and Italy, where she looked into the presence of Brazilian women in different sections of the sex industry. One of the study’s findings revealed that many of the discriminatory aspects faced by these women were also common to other Brazilian women from humble backgrounds who had also migrated, but who were not involved in prostitution. “In the minds of Italians, Brazilian women were excessively sexualized, resulting in prejudice and exclusion, even among those who were not prostitutes,” the anthropologist reports.

This perception was reinforced by other studies coordinated by Piscitelli in partnership with the Ministry of Justice, conducted between 2004 and 2005 at Guarulhos International Airport, in São Paulo. The anthropologist and her team monitored the return of Brazilian women who had been denied entry into Europe. “The number of women not admitted was huge. Many were not even involved with sex work, but were accused of migrating to engage in prostitution,” she reports. On the other hand, still in Brazil, the Federal Police also prevented Black women, perceived as poor and sexualized, from traveling abroad, under the justification of combating human trafficking.

At that time, Piscitelli sought to understand the consequences of the conceptual confusion between sex work and human trafficking. “Based on analysis of the working conditions of Brazilian women in Spain, I sought to understand whether those situations could be classified as trafficking,” she explains. The study revealed a discrepancy between Brazilian legal standards and international frameworks. On one hand, the Brazilian Penal Code defined trafficking as any act that facilitated the practice of prostitution abroad, effectively including nearly all the sex workers who migrated. “It is almost impossible for a person to travel abroad to work as a prostitute without some form of help—a contact or someone to receive them,” she says. The situation in Brazil changed in 2016 with the passing of Law 13.334, which began to define international human trafficking more precisely and established procedures to protect victims.

On the other hand, the definition adopted by the Palermo Protocol, created in 2000 as the main international treaty for combating human trafficking, determines that a situation must involve elements such as deception, violence, fraud, or coercion in order to be considered human trafficking. “Based on this protocol, hardly any of the women I talked to could be considered trafficked. But according to Brazilian legislation, they all would be,” compares the anthropologist. According to Piscitelli, indiscriminately mixing prostitution with human trafficking makes it more difficult for sex work to be recognized as a legitimate activity.

As part of a broader study about gender and migration, completed in December 2024 with funding from FAPESP, Piscitelli analyzed the presence of foreigners in Brazilian brothels. “They mainly work in border regions, in cities such as Tabatinga (Amazonas), which borders Colombia and Peru, and in border towns in the South of Brazil,” she says. In São Paulo, the study identified a little-discussed aspect about the reality faced by Bolivian women living in the city. “These women are traditionally associated with exploitation in clothing workshops, but the study noted a perceived presence of young Bolivian women engaged in sex work, something that had previously been rare outside border regions,” she adds.

Brazilian sex workers challenge imported legal models and propose new ways of thinking about a prostitute’s identity

Activism among sex workers in Brazil began in the 1980s, through the action of prostitutes such as Gabriela Leite (1951–2013) and Lourdes Barreto. “This movement became nationally structured in the following decade, opposing the narratives that reduce sex work to situations of exploitation or victimization,” comments anthropologist José Miguel Nieto Olivar from the School of Public Health at USP.

Between 2011 and 2013, Nieto Olivar took part in research analyzing the positions of Brazilian feminism on prostitution. At the time of the studies, according to the researcher, activists from the prostitute movement had a distrustful relationship with feminism. “This skepticism was based on the historical omission, by the majority of feminists, of the issues raised by sex workers,” he explains.

Since 2013, the situation has worsened, in part due to the rise of conservative discourse in national politics, influenced, among other factors, by the demands of religious groups. According to Nieto Olivar, the shift has been accompanied by some Brazilian feminist groups adopting legal models for regulating sex work from the Global North, especially Sweden, whose legislative framework is known for its neo-abolitionist approach.

Abolitionist and neo-abolitionist models, while sharing the premise that prostitution is a form of violence against women, differ in their practical and legal approaches. The first, formulated in the nineteenth century and reinforced by United Nations (UN) conventions throughout the twentieth century, proposes the abolition of prostitution through the repression of sex trade contexts, including pimps and brothel owners, but without directly criminalizing sex workers.

The neo-abolitionist model, which gained traction following legislative reforms introduced in Sweden during the 1990s, criminalizes clients and any form of purchasing sexual services, based on the premise that all sexual relations mediated by money are oppressive. “This proposal aims to discourage the demand for sex work, and therefore gradually eradicate the practice. It is criticized by sex worker movements for increasing their vulnerability by pushing them underground,” the anthropologist points out.

As a response, Brazilian prostitutes and activists, such as Monique Prada, Amara Moira, and Indianarae Siqueira, began formulating, in 2010, the concept of putafeminismo (a combination of the Portuguese words for “whore” and “feminism”). “The idea is to argue that feminism and prostitution are compatible,” summarizes Nieto Olivar. From the anthropologist’s perspective, this movement has helped broaden the horizons of Brazilian feminism by recognizing the profession as legitimate work and providing greater visibility to its demands.

The story above was published with the title “The market of desire” in issue 352 of April/2025.

Projects

1. Marks of desire: The construction of pleasure through body modification in online alternative pornography (n° 19/11134-4); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Jorge Leite Júnior (UFSCar); Beneficiary Cristiane Vilma de Melo; Investment R$301,263.30.

2. Digital platforms in Brazilian erotic-sexual markets: Restructuring and reorganization of the online sex and erotic trade (n° 20/02268-4); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Heloísa Buarque de Almeida (USP); Beneficiary Lorena Rúbia Pereira Caminhas; Investment R$683,635.58.

3. GEN-MIGRA: Gender, mobility, and migration during and after the COVID-19 pandemic – Vulnerabilities, resilience, and renewal (n° 21/07574-9); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Adriana Piscitelli (UNICAMP); Investment R$246,118.08.

4. Stories in prostitution: Incorporations, refusals, and (co)productions of perspectives (n° 24/16676-8); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Heloísa Buarque de Almeida (USP); Beneficiary Ana Carolina Braga Azevedo; Investment R$373,680.00.

Scientific articles

CAMINHAS, L. Dimensions of recognition through relational labour in erotic content creation in Brazil. New Media & Society. 2025.

CAMINHAS, L. Os mercados erótico-sexuais em plataformas digitais: O caso brasileiro. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais. Vol. 38, no. 111. 2022.

MELO, C. & SANTOS, H. Uma interpretação crítica da pornografia “inter-racial”: Racialização, tabu, representação e desejo. Discussões feministas sobre pornografia. Editora Devires. 2023. PASSAMANI, G. Um diálogo entre os estudos urbanos e o trabalho sexual de homens brasileiros em Lisboa, Portugal. Revista Ñanduty. Vol. 10, no. 15. 2022.

PISCITELLI, A. Miedo y trata de personas. Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad. No. 38, Rio de Janeiro. 2023.

OLIVAR, J. M. N. Sexuality and reproduction: Contributions of multisituated socioanthropological research with “digital natives”. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. Vol. 41, no. 4. 2025.