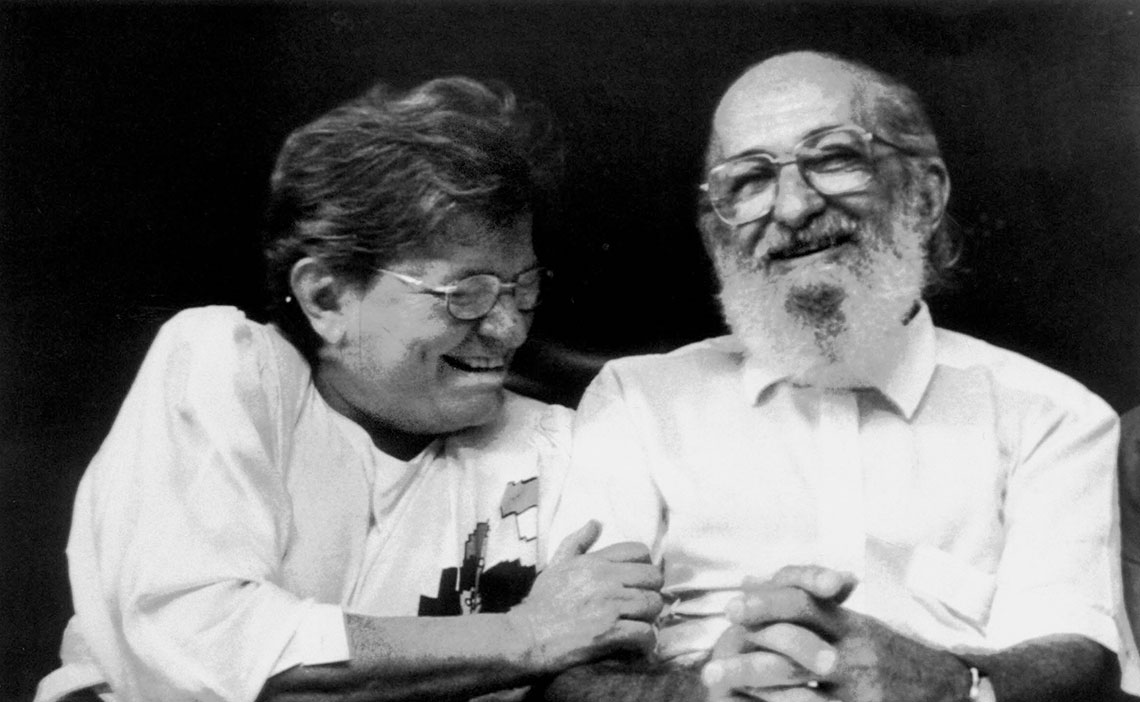

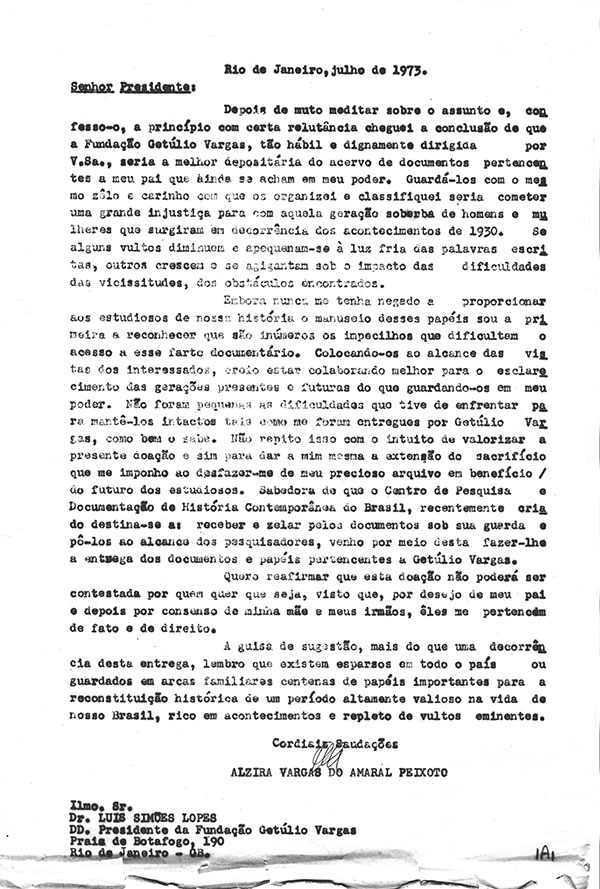

Until 1973, the only way of accessing the documents of Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954) for academic research was by consulting them at the home of his daughter, Alzira Vargas do Amaral Peixoto (1914–1992). That year, in a letter to agronomy engineer Luís Simões Lopes (1903–1994), then president of the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV), Alzira offered the collection to the institution, adding “by way of a suggestion,” that there were “scattered across the entire country or stored in family chests, hundreds of important papers for the historical reconstruction of a highly valuable period in the life of our Brazil, rich in events and full of eminent characters.”

The donation gave rise to the Center for Research and Documentation of Contemporary Brazilian History (FGV CPDOC), founded by the granddaughter of the political leader, sociologist Celina Vargas do Amaral Peixoto. After 50 years, above all, the CPDOC is known for having safeguarded the memory of Brazilian politics since 1930, through three main initiatives: The Personal Archives Program (PAP), such as that of Vargas and others until then “stored in family chests;” the Oral History Program (PHO), initiated in 1975 and based on interviews; and the Dicionário histórico-biográfico brasileiro (Brazilian historical-biographical dictionary), the first edition of which was published in 1984. From 2003, the CPDOC also began adding teaching, with undergraduate and graduate courses and the creation of the FGV School of Social Sciences.

On June 21, four days prior to the institution’s fiftieth anniversary, a formal ceremony in the Brazilian House of Representatives, in Brasília, paid homage to the CPDOC. The session was requested by deputy Luiza Erundina (PSOL-SP), ex-mayor of São Paulo (1989–1992) and minister of Federal Administration (1993–1994). In the request, Erundina wrote that the institute based in Rio de Janeiro “has consolidated itself as a paradigm of interaction between documentation and research, dissemination and knowledge, teaching, document conservation, and the preservation of Brazilian historical heritage.”

The case of Erundina is an example itself of how the center works. In addition to offering two testimonials, in 2001 and 2010, to the PHO, the parliamentarian donated her personal collection to the CPDOC in 2019, which was digitalized and made available online last May. Her documentation, composed of 14,225 pages, 342 videos, and 789 photographs, also illustrates in two ways the transformations that archival institutions are currently going through.

ALZIRA VARGAS DO AMARAL PEIXOTO COLLECTION, FGV CPDOC, AVAP GV ACGV 1973.07.14A letter sent by Alzira Vargas do Amaral Peixoto to Luís Simões Lopes, then president of the Getulio Vargas Foundation, in which she offers the collection of her father, Getúlio Vargas, to the institutionALZIRA VARGAS DO AMARAL PEIXOTO COLLECTION, FGV CPDOC, AVAP GV ACGV 1973.07.14

One is technical. When Erundina’s documents arrived at the CPDOC, among the papers, tapes, and photos there was an element still uncommon in the day-to-day of the institution’s professionals: an external hard drive, containing text, image, video, and audio files. The content of this device, whose purpose is exactly to store information, imposes some challenges for the person cataloging it, as sociologist Carolina Gonçalves Alves, coordinator of documentation at CPDOC, explains.

“We always digitize the documents, but those which already arrive in this format bring new questions. Among them, how do you organize and preserve a large volume of digital documents? How do you deal with formats that may be discontinued? The arrival of digital documents brings new challenges to the management, conservation, and access of the archives,” says Alves. According to the sociologist, among the problems are the multiplicity of formats and the resolution of the images. “The physical photographs are always scanned in standard formats for preservation and access. But, when the photo is digital, sometimes the resolution is low and cannot be changed. It is important that the researcher be aware of this.”According to anthropologist and historian Celso Castro, current director of the CPDOC, the great technological transformation of the last 20 years, with increased document digitalization and dissemination of the internet and audiovisual recording, has impacted the way the production of collections and the work of research about them is done. Besides the technical challenges, Castro also mentions a procedural change introduced by the pandemic: “It brought the possibility of conducting interviews remotely to the forefront.” Before, interviews were always in person, with rare exceptions.

The second way by which Erundina’s collection signals this period of change in the CPDOC is the integration of documents of a female political leader. The measure reflects the effort for greater diversity in the institution’s catalog. In 2015, its researchers found that, of the set of around 230 personal archives, with more than 2 million documents, only 11 were of women. Since then, the collection has only been added to with archives from women: today, there are 20, from a total of 239, reports Alves. “Very little of the total collection were files from women. It is clear that this can be explained due to the Brazilian political elite having been mostly made up of men, but we began actively looking for more archives from women,” observes Castro.

A consequence of this search was the change made that same year in the archive policy of the CPDOC, a two-page document that defines the institution’s profile and guides the acquisition of new archives. Where it read that the collection was made up “of personal archives of men with distinguished work in contemporary Brazilian public life,” it now states that they are from “men and women.” Besides Erundina, also in the catalog, among others, are the archives of two participants from the National Constitutional Assembly of 1933: lawyer and union leader Almerinda Farias Gama (1899–1999), who served there as a class delegate, and physician Carlota Pereira de Queirós (1892–1982), the first female federal deputy of Brazil. Alves points out that Gama is the only Black woman with a personal archive in the CPDOC.

Another initiative was the creation last year of the Women’s Archives Network (RAM), in partnership with the Institute of Brazilian Studies of the University of São Paulo (IEB-USP). According to Alves, the idea arose in a virtual seminar held in 2020, during the pandemic, in which researchers from IEB-USP reported similar concerns about the female invisibility in their collections. “In the mapping that we did in the two institutions that year, we found only 37 archives in total,” reports the sociologist, one of the coordinators of RAM. “With the network, we intend to mobilize other institutions to ask about this representativity.” Today, the group also includes the Brazilian National Archive and the Moreira Salles Institute.

Alzira Vargas do Amaral Peixoto Archive, FGV CPDOC, AVAP PHOTO 074_05 Alzira Vargas in Italy, in April 1937, with the portrait of her father, president of Brazil at the time, in the backgroundAlzira Vargas do Amaral Peixoto Archive, FGV CPDOC, AVAP PHOTO 074_05

In the archives, in general, the technological challenge and the increased efforts to include women and other little-heard groups has converged in recent years. This causes transformations even in documentation that has already been stored for a long time. One central element of cataloging is the use of metadata and indicators, which enable what is found within each document to be identified and guide the work of the researchers. However, the keywords used throughout the decades to help search in the texts and images reflect the scenario in which the archive was created. Therefore, the prevalence of archives of men is not the only patriarchal mark on the collections: even the captions of photographs can hide the presence of groups such as women, and Black and Indigenous people.

In the case of the CPDOC, Alves observes that keywords such as “feminism” or “women’s rights” did not exist and were added based on the work of digitalizing the archives of women, some of which had been stored in the institution since the 1970s. “Today, we are living in a time in which civil society and researchers are asking new questions of the archives. And these questions have mobilized us to work on the presences we did not previously see. A whole world has opened up and led the archival institutions to look at their collections in another way,” says the sociologist.

Similar transformations, but not identical, affect another aspect of the work of the CPDOC: the PHO, created through the initiative of sociologist Aspásia Camargo two years after the arrival of the Vargas archive. The institution was a pioneer in Brazil in oral history, the emergence of which, in the 1940s, is attributed to US historian and journalist Allan Nevins (1890–1971), who took advantage of the spread of portable recorders.

Almerinda Farias Gama Archive, FGV CPDOC, AFG PHOTO 004_1 Lawyer and union leader Almerinda Farias Gama during the election of class representatives for the National Constitutional Assembly of 1933. Gama is the only Black woman with a personal archive in the CPDOCAlmerinda Farias Gama Archive, FGV CPDOC, AFG PHOTO 004_1

“At that time, the oral history method was not well known or valued in Brazil,” states Castro. “The CPDOC was a pioneer both in the production of interviews, which generate documents that are filed and later made public, as well as in methodological discussion,” he says. In July this year, the institution hosted the 22nd International Oral History Association Congress, of which it was one of the creators. The center also published the Manual de história oral (Oral history manual) — the first edition of which was called História oral: A experiência do CPDOC (Oral history: The experience of the CPDOC) — by historian Verena Alberti. This year, it launched the volume História oral e audiovisual: Experiências do CPDOC (Oral and audiovisual history: Experiences of the CPDOC), edited by Castro, historian Vivian Fonseca, and communicator Thais Blank.

The first oral history interviews precede the creation of the program. In 1974, Vargas’s own daughter, Alzira, who exerted political influence over her father, spoke with the researchers. In the same year, it was the turn of Juscelino Kubitschek (1902–1976), former president of the Republic. Today, the program is home to over 2,500 interviews and 8,000 hours of recordings, the majority transcribed. From 2006, the interviews began also being done on video, when authorized by the interviewee. The Audiovisual and Documentary Center (NAD), created in the same year, shares the team, space, and equipment with the PHO. “When we started filming the interviews, we renewed our reflection on oral and audiovisual history,” says Castro.

According to historian Vivian Fonseca, coordinator of the PHO, recording in video is still not fully accepted among oral history fans. Researchers opposed to moving image feel that the interviewees do not feel as at ease in front of a camera as they do with a recorder. On the other hand, the video recordings favor the production of documentaries and other products for more widespread dissemination. “The integration with the documentary center led to a series of small changes in our dynamic,” says Fonseca. “We can, for example, use more than one camera, which is not common in oral history. Additionally, we made changes in the studio to make it more interesting from an aesthetic point of view. And we avoid sounds and comments while the interviewees are speaking.”

Among the recent audiovisual products from the CPDOC is Magia e poder: Fronteiras entre o sagrado e o profano (Magic and power: Borders between the sacred and the profane, 2019), directed by Gyovanna Alves and Lucas Pipolos. The film is based on the archive of anthropologist Yvonne Maggie, from Rio de Janeiro, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), donated to the CPDOC. In the 1970s and 1980s, Maggie did fieldwork in Candomblé and Umbanda worship sites in Brazil (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 295).

Reproduction, Audiovisual and Documentary Center, FGV CPDOCExcerpt of the documentary Magia e poder: Fronteiras entre o sagrado e o profano (2019), produced by the CPDOC from the archive of anthropologist Yvonne Maggie from Rio de JaneiroReproduction, Audiovisual and Documentary Center, FGV CPDOC

In the last decades, the CPDOC has amplified its scope in both the personal and the oral history collections, but maintained the guideline of dedicating itself to the political and social history of republican Brazil. The starting point, however, is not the Proclamation of the Republic, in 1889, but the events that, from 1922, culminated in the revolution of 1930. The first set of collections to arrive at the center, other than the one belonging to Vargas, contained the papers of Oswaldo Aranha (1894–1960), his minister of justice, finance, and external affairs, and Gustavo Capanema (1900–1985), his minister of education. According to the report by Celina Vargas to the PHO, the intention was to create an institution to house “an archive not of Getúlio Vargas but of the time of Getúlio Vargas.” Later, this inaugural archive would also be the first of the CPDOC to be digitalized in 2000. The founding of the PHO was based on the institution’s inaugural project, “The trajectory and performance of the Brazilian political elite from 1930 to the present day.”

Currently, the archives and interviews are linked to projects of different themes, such as soccer, based on research by sociologist Bernardo Buarque de Hollanda (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 322); major sporting events, heritage, and urban politics, topics investigated by Fonseca; and diplomacy, thanks to studies done by international relations researchers, like Matias Spektor. The arrival of the collection of anthropologist Roberto Da Matta, in 2022, inspired a partnership with leaders of the Apinajé Indigenous people, to identify ethnicities and individuals in the photographs. Once the research is concluded, interviews and other documents are incorporated into the CPDOC collection.

This way, research and documentation are mutually aligned, in accordance with the name of the institution. One of the best-known results of the practice is the Dicionário histórico-biográfico brasileiro, (Brazilian historical-biographical dictionary) a project initiated by historians Israel Beloch and Alzira Alves de Abreu (1936–2023) in 1974. The first edition, which was published 10 years later, had four volumes and 4,493 entries. The second version, from 2001, had 6,620 entries distributed in five volumes, besides a CD-ROM version. Completed in 2010, the third edition is available for free online. Of the 7,553 entries, 6,584 are biographical and 969 are thematic, that is, related to institutions, events, and political concepts. For Castro, the dictionary is “the product of greatest public impact in the history of the CPDOC,” being consulted by researchers, journalists, and political figures across Brazil.

Reproduction, Oral History Program, FGV CPDOCIn clockwise order, some of the researchers interviewed for the “Memory of social sciences in Brazil” project: Alba Zaluar, Gabriel Cohn, Fernando Limongi, and Alzira Alves de AbreuReproduction, Oral History Program, FGV CPDOC

In 2007 the CPDOC began conducting interviews with social scientists. The initiative followed on from one of the first large oral history projects carried out by the center, from 1977 to 1979, in partnership with the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP): mapping of natural science production in Brazil. Coordinated by sociologist Simon Schwartzman, then professor of FGV’s own Brazilian School of Public and Business Administration (EBAPE), the original proposal generated 69 interviews, which were incorporated into the institution’s collection.

Schwartzman says that he had no practice in oral history when he dedicated himself to the work. “In the interviews, the scripts were very open. We asked about the person’s career, how they had gotten interested in science. The focus was on the scientific institutions,” he recalls. And completes: “The material is very rich. Some interviews last many hours, and their transcriptions can reach 200 pages.” The project resulted in the publication of the book Um espaço para a ciência: A formação da comunidade científica no Brasil (A space for science: The formation of the scientific community in Brazil; Companhia Editora Nacional/FINEP, 1979), by Schwartzman.

Currently, the sociologist is participating in the proposal to create a research project in which he intends to revisit the topic. “I want to do a round of interviews with the new generation of leaders and compare them with the reports of the generation from the 1970s that I collected for the CPDOC,” he concludes.

Book

CASTRO, C. BLANK, T. e FONSECA, V. História Oral e Audiovisual: experiências do CPDOC. Rio de Janeiro: FGV, 2023.