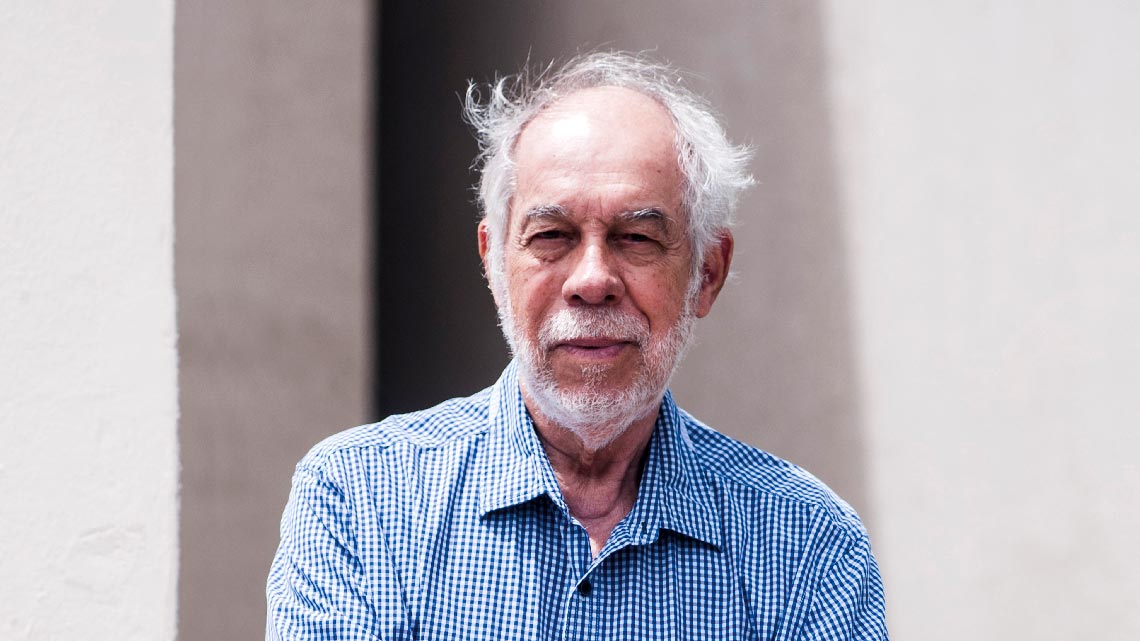

The résumé of biochemist Jorge Almeida Guimarães, 84, paints a picture of a restless researcher. In a country where academic mobility is low, he has worked as a professor at five different federal universities—the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Fluminense Federal University (UFF), the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), and the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS)—as well as at the São José do Rio Preto School of Medicine (FAMERP) and the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). He also spent three decades working in management at agencies such as the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), and the Brazilian Agency for Industrial Research and Innovation (EMBRAPII).

Guimarães’s career path is not only unusual, it is also totally unexpected. One of nine children of a peasant couple from Campos de Goitacazes in the north of Rio de Janeiro State, he only began attending school at age 10. He seized an opportunity—a spot at an agricultural school near the settlement where they lived—and made it his gateway to a career in biochemistry, with an emphasis on protein chemistry.

In September, he stepped down as president of EMBRAPII after seven years in charge of the agency. Shortly before leaving, he commissioned a team of researchers to produce a book titled Ciência para prosperidade sustentável e socialmente justa (Science for sustainable and socially just prosperity; EMBRAPII, 2022), which lists the science, technology, and innovation challenges faced by Brazil. He retired from UFRGS in 2008, but continued to supervise graduate students at the institution and at the Hospital de Clínicas in Porto Alegre. In the following interview, Guimarães looks back over his long career.

Field of expertise

Molecular Biology

Institution

Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul

Education

Degree in Veterinary Medicine from UFRRJ, PhD in Molecular Biology from the São Paulo School of Medicine at UNIFESP

Scientific output

197 articles, 1 book, and 28 book chapters

How did the son of a pair of farm laborers establish an academic career at a time when few people took that path in Brazil?

There weren’t many expectations for a person like me. My father never went to school. He learned to read and write from my mother, who only attended elementary school. We lived the farm life. My mother had nine children and only me and one of my sisters, who is ten years younger than me, went to college. My mother had tuberculosis after I was born. Penicillin had just been developed and my father spent what little money he had—which wasn’t much—to save her. But it left him with nothing. He had a storage unit and a small property that he had to sell. Two of my older brothers had moved to Rio de Janeiro and convinced my parents to follow them. My father got a job at the city hall, but he couldn’t adapt. At that time, at the end of the Second World War, he found out about a major agrarian reform project by Getúlio Vargas in the Itaguaí region, between the old Federal District and the state of Rio, to settle the families of Japanese immigrants and to give land to soldiers returning from the war. My father went there and convinced a former soldier to let him be a sharecropper on his property. That’s how we started: my father, my mother and I, to plant, cultivate, and harvest crops. But there was no school nearby. A year or two later, the project was expanded and my father was given some farm land. I was 10 years old when he decided that I should go to school.

Could you read at that point?

My father taught me the basics of math: the weights of things, size, volume. But not how to read and write. The closest school was “Ponte dos Jesuítas” in Santa Cruz, on the Federal District side—we were in the state of Rio. There was a river that separated one region from the other. From time to time, our stream, called the São Francisco River, would flood and the precarious bridge would collapse. To get to school, I had to swim across the river. I completed elementary school there. I was an excellent math student. One of the agronomists from the Ministry of Agriculture involved in the land division process told my father that the government was opening a rural university nearby that had a technical school, and that he should send me there. It was the Ildefonso Simões Lopes Agrotechnical School, and the competition for spaces was fierce. It was based on the model of a military school and provided all the necessary support: food, clothes, shoes, a dormitory, discipline, sport, rural work. I applied, passed, and spent four years boarding in the old gymnasium school system. Soon after, the school opened its technical course, equivalent to the old scientific course. I then spent seven years as a full-time student. The subject I was most interested in was chemistry.

Why did you choose to be a veterinarian?

At what was then the Rural University of Brazil (RUB) and is now UFRRJ, there were only two higher education courses: agronomy and veterinary science. To do chemistry, I would have had to change university and my family wouldn’t have been able to support me. That’s when I met a professor of biochemistry on the veterinary course: Fernando Braga Ubatuba. He was my scientific mentor. Many years later, I invited him to work in my laboratory when I was a professor at UFRJ. He worked with me until he died.

How did you meet him?

Ubatuba was an incredible physician, biochemist, and educator. He was also a researcher at the Manguinhos Institute, which is now FIOCRUZ. The only place he taught part-time was the veterinary clinic at RUB. Biochemistry was a similar path to chemistry. I took the entrance exam for veterinary science, which in addition to the written tests, included an oral exam with four professors. He was there and he asked me: “Why do you want to become a veterinarian?” I responded: “Because I want to work with you.” I passed and when the first semester ended, he offered an opportunity to all students to work with him during the holidays. “But it has to be at my lab in Manguinhos.” It was me and one classmate. In the second semester I became a teaching assistant.

Sometimes our stream would flood and the precarious bridge would collapse. To get to school, I had to swim across the river

And how was your first contact with scientific practice?

In front of RUB was what at the time was called the Agricultural Research Institute of the Ministry of Agriculture, now known as EMBRAPA. Two German veterinarians worked there, studying toxic plants and mineral deficiencies in animals. They convinced a farmer to sacrifice a sick animal so they could take a sample of its liver to analyze for mineral deficiencies, but they sent the sample to Germany for analysis. They asked Ubatuba for help, and he said: “Jorge will do it—I’ll train him.” I spent three years working on the topic of mineral microelement deficiencies in cattle and sheep. At the end of the course in 1963, I started a specialization course in the physiology of microorganisms, at the then Institute of Biochemistry of the University of Paraná [currently UFPR], directed by Professor Metry Bacila [1922–2012]. I returned to RUB on March 30, 1964. And on April 1, the dictatorship began.

How did that affect you?

I had been president of the academic board and Ubatuba was considered a leftist. There was a barracks nearby and the soldiers came to the university cafeteria, climbed onto a table and started reading out the names of students and other people who were to be arrested, including mine. But fortunately they didn’t find me, because I had switched to the Ministry of Agriculture side of campus. I was extremely lucky, and that allowed me to get away from the RUB environment. I found a former chemistry teacher from the Agrotechnical School who offered me a job at a multinational company where he worked in Resende. The company was Lederle, the Brazilian division of Cyanamid. I was in the industry for a long time. I was engaged and earning well, but I was still really interested in academic life. I stayed in the private sector until things calmed down at RUB. When they began hiring for a teaching assistant, I applied. I passed and went back to working with Ubatuba and the German researchers. Then in 1968, Ubatuba was arrested. He was escorted by soldiers to his biochemistry classes—it was really terrible. At the end of 1968, he told me: “We’re going to have to leave, but first you need to get your graduate degree.” He and his colleagues at FIOCRUZ decided that I should switch to studying proteins at USP’s newly created Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine, working under Professor José Moura Gonçalves [1914–1996].

Did you follow their advice?

No, because it changed. Moura Gonçalves became director of the School of Medicine and Ubatuba said “he won’t have time to supervise you.” So I went to do my master’s degree at the São Paulo School of Medicine [EPM], supervised by the couple José Leal Prado [1918–1987] and Eline Prado [1921–2007], who welcomed me with open arms. I broke the prevailing internalism a little. I went there at the end of 1969, and on April 1, 1970, Ubatuba was removed from office along with nine other FIOCRUZ researchers, in an event known as the Manguinhos Massacre. The group that we formed at RUB was disbanded. After six months at EPM, José and Eline Prado decided that I should go straight onto a doctorate, which was rare at the time. Things got complicated because when my two-year master’s period ended, RUB demanded that I return. That was a difficult issue.

How did you resolve it?

The EPM director tried to request my transfer, but RUB refused. In the end I was able to come to an arrangement with the director of the RUB Chemistry Institute. Due to reforms, RUB had courses in other fields by that point, including chemistry. He proposed that I teach biochemistry at RUB on Fridays and Saturdays and the rest of the week I do my doctorate in São Paulo. Then a position opened at EPM and I was approved as an assistant professor of biochemistry. The role was part-time. I had a family and the partial salary for 20 hours of work was not enough. Colleagues from EPM and USP’s biochemistry department convinced FAPESP to give me a salary supplement grant. Thus, I became a FAPESP grant recipient from May until December 1972, when I defended my PhD at EPM.

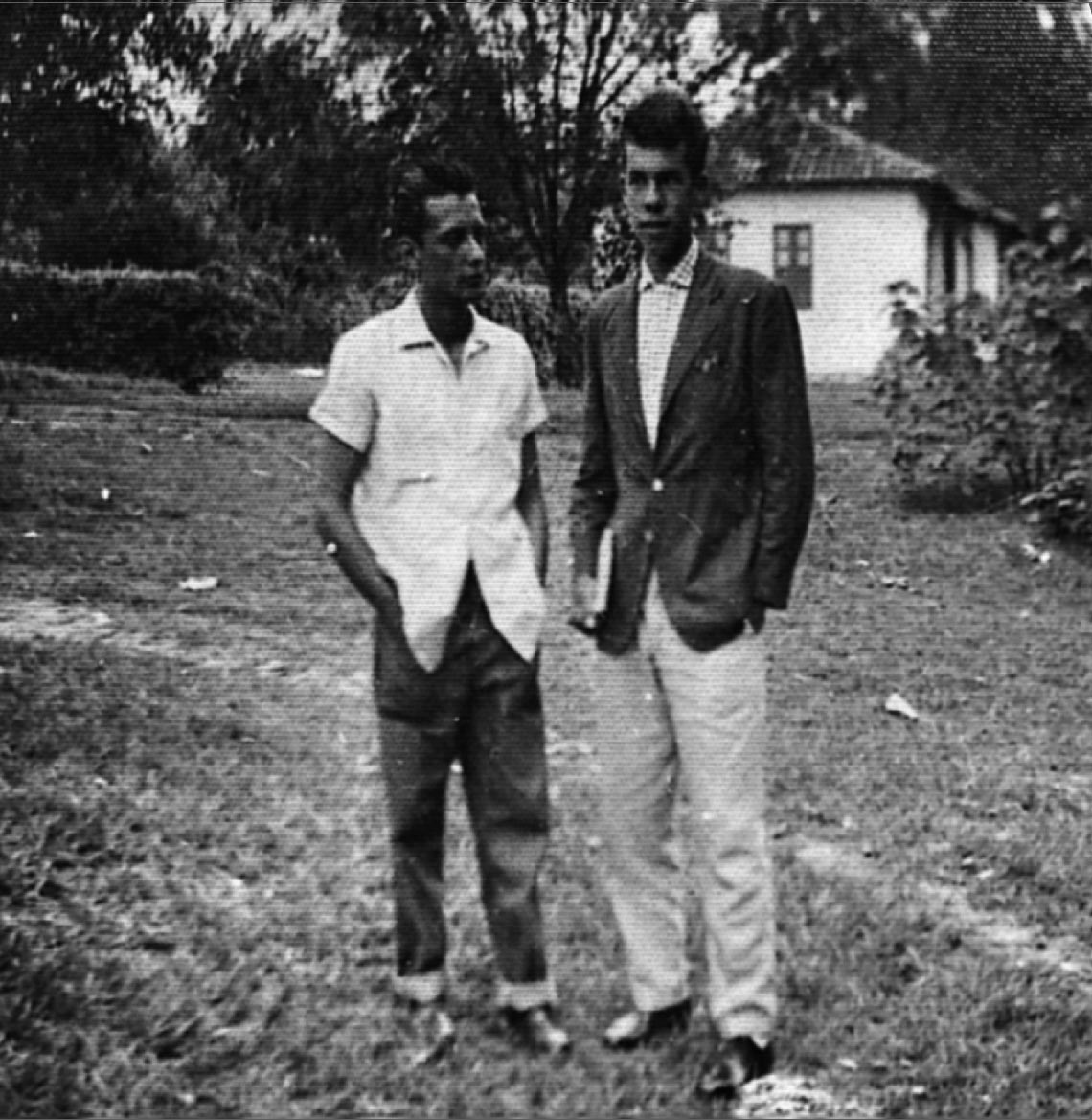

Personal archive

Guimarães (right), on the UFRJ campus when he was a veterinary studentPersonal archiveI wanted to talk about your scientific contribution. You worked with protein chemistry. What exactly did you do in your PhD?

At EPM, I started working with proteins, studying the enzymology of bioactive peptides, which are involved in physiological processes. The biggest contribution I made in this area was my doctoral thesis, which was about an enzyme known as kinin-converting aminopeptidase from human serum. It had a lot to do with the discovery of bradykinin, an antihypertensive agent present in pit viper venom, by Maurício Rocha e Silva [1910–1983]. The 9-amino acid chain of bradykinin is found within a larger molecule called kininogen, a protein in the human body. It is part of the kallikrein–kinin system, which opposes the renin–angiotensin system, a well-known cascade of biochemical processes that constricts blood vessels and causes increased blood pressure. One of the steps of the renin–angiotensin system converts a larger peptide into a smaller peptide, which is the bioactive one. So we thought: “There must be something similar in the kinin system too.” We found that what the enzymes do is release a larger peptide called lysyl-bradykinin, which has 10 amino acids instead of nine. And there is a slightly larger peptide called methionyl-lysyl-bradykinin, which has 11 amino acids. I studied the enzyme that converts larger kinins to bradykinin.

Did you also study this topic in your postdoctoral research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA?

José and Eline Prado returned from the US at the beginning of 1972 and arranged for me to do a postdoc at the NIH, in the city of Bethesda. I started working with phenomena related to blood clotting. I was able to study kininogen, the precursor of kinins, in more depth with a group from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], working with researcher Jack Pierce. One important discovery we made was that people who were deficient in a certain type of kininogen could suffer from blood clotting defects. This study, from 1975, is one of my most cited.

In addition to RUB and EPM (now UNIFESP), you were also a professor at Fluminense Federal University and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro before you settled in Rio Grande do Sul. Moving around so much is unusual among researchers here in Brazil. To what do you attribute this?

I worked at other institutions as well. A director at EPM had a brother who was director of the São José do Rio Preto School of Medicine. He complained that he was having difficulty finding biochemistry professors. José Leal Prado and the EPM director at the time decided that I should help out at the school, together with Cláudio Sampaio, a biochemistry colleague of mine. So we went there to teach. I also spent some time at UNICAMP. Professor José Francisco Lara of USP’s biochemistry department was invited by Zeferino Vaz [1908–1981], then dean of UNICAMP, to set up what would be the first biotechnology center in Latin America. Lara raised substantial funds and invited some researchers. There were about eight of us. Zeferino ended up leaving his position and the first thing the new dean Plínio de Moraes did was put an end to the project. I’m always asked why I moved between universities so much. As a joke, I usually answer that it was for two reasons. The first is that when my flaws are revealed, it’s time for me to leave. The second is when someone starts thinking I might be a good candidate for dean, then I have to leave. But all jokes aside, when you move, you start from scratch, a lesson I learned from Professor Ubatuba teaching students from the very beginning of their scientific education, and I always found this type of challenge stimulating.

I’m always asked why I moved between universities so much. I’ve always found the challenge of starting from scratch exciting

You left EPM to become a professor at UFF, but you stayed there for a very short time. Why?

Part of our RUB group went to UFF. I had separated from my first wife, I wanted to leave the EPM environment so I applied for a position at UFF, against the will of José and Eline Prado. On January 2, 1980, I started my job as professor of biochemistry at UFF. It was a horrible, difficult period. The Department of Physiological Sciences had 70 faculty members and the vast majority had multiple jobs and were not dedicated to science. Our small group managed to develop a strong teaching and research system in the discipline of biochemistry. As a result, a small group of five professors/researchers went to the Brazilian Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (SBBQ) conference in Caxambu in May 1980, where I was elected president of the SBBQ for 1981–1983. It was an enormous honor. But when we got back to Niterói, we were punished for our absence by a boss who had five different jobs. It was a year and a half of tribulation. When my period of leave from EPM was coming to an end, I thought about going back to São Paulo. Leopoldo de Meis [1938–2014], who was both a friend and my vice president at SBBQ, told me: “Come and work with our new group at UFRJ’s Department of Medical Biochemistry [DBM].” I resigned from UFF, resumed my position at EPM, and from there I transferred to UFRJ. As soon as the formal transfer came through, Leopoldo said: “You will be head of the department instead of me.” I took over and had to dismiss several people who weren’t doing any research, weren’t in tune with modern teaching methods, and interfered with the plan to build a really strong biochemistry department. I headed the department from 1982 to 1985. I gained many enemies, but also lots of recognition for defending science and the key principles of the university. I was then named director of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences [ICB], from 1986 to 1990.

In the 1990s, you became scientific director of CNPq. How did you end up in Brasília?

In 1990, the Collor administration appointed José Goldemberg as Secretary of Science and Technology. He visited UFRJ and said he would like someone from the university on the CNPq team. So I joined as a director at CNPq, first in programs, then in science. It was a huge challenge. Collor didn’t give me much money at CNPq, but I managed to create some good initiatives, such as the integrated project, the engineering support plan, and PIBIC (Institutional Program for Undergraduate Research Grants). There was already a preliminary initiative at CNPq in this regard, but with very few grants made available. The aim of PIBIC was to offer grants to 30,000 students, awarded in the form of quotas depending on the number of spaces offered by each master’s course. The objective was to allow universities and institutions to select grant recipients and to provide them with a model capable of improving scientific education in Brazil. In the program’s first round in 1991, 11,000 grants were awarded.

You were one of the longest-serving presidents of CAPES, staying 11 years and 3 months between 2004 and 2015. What do you consider your most important achievement during this period?

We implemented many initiatives and programs. That includes extraordinary expansion of the journal platform, the incorporation of basic education and open university, the restructuring of the organization from three to seven directors (including a director of international cooperation), and the increased number of professional master’s degrees. At CAPES, I created the equivalent of the PIBIC program but for teacher training, called PIBID (Institutional Program for Teacher Training Grants). The PIBID program awarded 100,000 grants within a short time frame. When I started in February 2004, I realized we needed to resume the National Graduate Plan [PNPG]. The three plans formulated since the 1970s were very important. I appointed a committee, led by Professor Cesar Sá Barreto, former dean of UFMG, and we created the 2005–2010 PNPG. In early 2010, I set up a new committee, once again led by Professor Sá Barreto. The resulting plan covered the period from 2011 to 2020. When I took office, I confirmed my conviction that university courses needed more autonomy, especially those graded 6 or 7, which have greater weight and experience. We created PROEX [Academic Excellence Program], through which resources are transferred to the coordinators of graduate programs, who are in charge of the program’s policy. If the concept fails, they leave the program. With support from politicians like Tarso Genro, Fernando Haddad, and Henrique Paim, we were able to raise the CAPES budget from R$500 million in 2004 to R$7.1 billion when I left in 2015.

Personal archive

In 1995, as a visiting researcher at the University of Arizona, USAPersonal archiveYour most recent job was leading EMBRAPII, which has created a different way of fostering innovation in companies. What was the impact of the work?

EMBRAPII is based on a different concept because it is a private institution, free of the obstacles that affect the operations of funding agencies. It will not save Brazilian industry on its own, but it has achieved results that I consider extraordinary. It uses the triple helix model of scientific and technological innovation, which refers to the joint action of academia, industry, and the government. Here in Brazil, we created the CNPq, CAPES, BNDES, FINEP, and FAPESP before the 1970s, and no one was in charge of cultivating interactions between universities and companies. For BNDES and FINEP, this was an obligation. But they opted to lend money to companies. Companies do not borrow money to innovate, which is a risky activity. The triple helix model solves this issue because the government contributes some of the investment, the “carrot” part of the incentive. EMBRAPII provides one-third of the funds allocated to each project. Its research units, which operate at universities and research institutions, account for an average of 17%—not in cash, but in equipment, machines, personnel, and existing infrastructure. In total this adds up to 50%. The company puts in the other 50%, knowing that the groups are highly qualified, rigorously selected, and accredited. The management process is unbureaucratic, with no rules on how to spend public money. EMBRAPII could play a much greater role if the government realized its importance, but that hasn’t happened recently because the government was so disinterested in education and science. The expectation was to have three times as much money. Still, it functioned well and demonstrated that the model works. And it must be maintained. More than 2,000 projects were contracted by 1,400 companies. In the mining sector, ArcelorMittal, Vale, and CBMN all have more than 10 projects each. EMBRAER has 18, even with four of its own centers of excellence. There are many things it prefers to do with EMBRAPII rather than burdening its experts with problems that EMBRAPII can resolve. It’s a tremendous win-win situation.

In 1997, you settled at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, where you retired in 2008. What did you achieve there?

I arrived here in Porto Alegre with my wife Celia—she joined the Biophysics Department through a competitive hiring process and I transferred from UFRJ to the UFRGS Biotechnology Center. I had a background in the area of poisons and I found a really interesting subject here: a caterpillar, Lonomia obliqua, known locally as the fire caterpillar, which is found in the forests and can cause fatal hemorrhages. Due to deforestation, it began proliferating in peach, plum, and apple orchards on farms in Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. This topic has attracted many undergraduate and graduate students. One project by a student called Ana Beatriz Gorini da Veiga, who is now a professor at the Federal University of Health Sciences in Porto Alegre (UFCSPA), unlocked the secret of the caterpillar’s spines. A subepithelial tissue, a bit like a gland, feeds the bristles, and people picking fruit, for example, brush against them, injecting themselves without realizing. More recently, we have been working on topics such as the Zika virus and the COVID-19 virus, and we’ve made several contributions.

For example…?

We published a study on the Zika virus that I consider of the utmost importance, because it showed us that women infected by the virus, even after recovering from the disease, are more likely to experience severe pre-eclampsia when they become pregnant. I have also been doing a lot of scientometrics, including a paper recently published in the journal Scientometrics on the difficulties faced by countries with little international cooperation, or on the contrary, those that rely exclusively on this type of collaboration. They need to realize that a country can’t develop if it doesn’t do the minimum in science and proper training of its own human resources. These activities have distracted me a lot.