In 1982, American anthropologist Karen Strier, then 23 years old, visited the forests of Caratinga in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais for the first time. She was immediately captivated by the northern muriquis (Brachyteles hypoxanthus), the largest monkey species in Brazil, endemic to the Atlantic Forest. “They’re so acrobatic, charismatic, and charming,” she recalls, and as vegetarians, they give off a pleasant cinnamon scent. Muriqui males are the same size as the females and they are a peaceful species, in direct contrast with the displays of dominance she had witnessed years earlier among baboons in Africa. Since then, Strier has divided her time between her work as a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the US and her field research in Brazil.

Perhaps because of the warm welcome she received from the primates in Brazil (humans included) or the tropical climate of the Atlantic Forest compared to the harsh winters of the northern USA, she says she feels more alive when she is in Minas Gerais. Caratinga locals have promised to throw her a party next year to celebrate her 40th year studying the endangered apes, about which little was known when she first arrived. The population has undergone a remarkable recovery, although their numbers are still below the level needed to ensure the continuity of the species.

She was president of the International Primatological Society until the turn of the year, and she returned to Brazil in February to help formulate a recovery plan for the muriquis in São Francisco Xavier, a village in the municipality of São José dos Campos. She also visited the Ibitipoca Commune in Lima Duarte, Minas Gerais, to see the muriquis there for the first time in more than six months. She spoke to Pesquisa FAPESP via video call from her accommodation in Vila do Mogol, Ibitipoca, before returning to Madison, where she teaches and lives with her biochemist husband and their cat.

Fields of expertise

Anthropology & Primatology

Institution

University of Wisconsin–Madison, USA

Education

BA Special Major in Sociology/Anthropology and Biology from Swarthmore College (1980), MA (1981) and PhD (1986) in anthropology from Harvard University

Published works

144 articles, 14 books

Tell us about the meeting in São Francisco Xavier in early February.

São José dos Campos city hall got in touch with me because they had information about muriquis in the surrounding forests. They had read my book Faces in the Forest and wanted my opinion. Usually, it’s the biologists who start field research projects, but in this case it was the local community that called on us to develop a primate conservation plan, with a focus on the muriquis. Then there was the COVID-19 pandemic, but we kept working. In June 2021, after I had been vaccinated, I came to continue my long-term research and help my colleague Fabiano de Melo, from the Federal University of Viçosa, and to continue discussing this project in São Francisco Xavier. Now in February we’re getting started again, with everyone wearing masks and keeping 2 meters apart, and heavy use of YouTube. The first thing to do will be to better understand primate populations in the region—their size, spatial distribution, and connections between them—as the basis for a conservation plan. Fabiano intends to use drones, something he’s done in other areas, to determine how many primates live there.

Are you in Ibitipoca now?

Yes. The work here is an independent supplement to my long-term research, which began 39 years ago in Caratinga, Minas Gerais. It’s one of the longest primate studies in the Americas, which has allowed me to train nearly 80 Brazilian scientists. Decades ago, a rural entrepreneur called Renato Machado from here in Ibitipoca contacted me and my colleagues Fabiano, Sérgio Lucena Mendes, who is the director of INMA [the National Institute of the Atlantic Forest], and Leandro Jerusalinsky from the CPB [the National Center for Brazilian Primate Research and Conservation]. There was a small population here—just four males—and later there were only two, meaning they needed a lot of help to recover. I had already observed in Caratinga that it is the females that leave the group and the males that stay. So in an isolated group, only males remain and no more offspring are born. In this project, which is called Muriqui House and is managed by Fabiano and Fernanda Tabacow, we looked for females from other isolated populations—almost all of them had at least one trying to leave—and brought them to live and reproduce with the males of the group. Within a year, a baby was born and the group was healthy. The plan is to create two groups to facilitate genetic exchanges between the females. Another parallel project is working to restore the forests where the muriquis live. Here, there are northern muriquis, in São Francisco, it’s the southern species.

What was primate research like in the 1980s when you first started studying muriquis?

In the US, for many biologists who go into anthropology, primates are good models for understanding human social behavior and evolution; since we are primates, there is an evolutionary connection. I was looking for an animal model to study how ecological variables, such as diet, could influence social behavior and group hierarchies. But in the early 1980s, most of the studied primates were from Africa and Asia, such as baboons, chimpanzees, and gorillas. Howler monkeys were the only ones from the Americas studied in the field in any depth. Coincidentally, my supervisor at Harvard, Irven DeVore [American anthropologist, 1934–2014], was narrating a film about muriquis made by Russell Mittermeier [American primatologist] for the WWF [World Wildlife Fund] and asked if I wanted to see the film before it was distributed. I found the animals fascinating, and after searching in the library, I discovered that almost nothing was known about the behavior of the species, which was already critically endangered. I needed to find out what they eat and the seasonality of their diet, predict their social behavior, and test theories developed for other primates. In 1982, I went to Caratinga with Mittermeier and he introduced me to the muriquis.

What was your first encounter with them like?

It was on a trail through the forest. First I smelled them—a nice cinnamon smell because they’re vegetarians. Then I saw them. They’re so acrobatic, charismatic, and charming. I loved it. I was really curious to see how they behaved, and from the very beginning it was very clear in my mind that everything I learned could be applied to their conservation. I only stayed in Caratinga for a short time that year, but later I came back to spend 14 months collecting data for my PhD research. In 1983, there were no cell phones or internet. To make a call, you had to go into town and wait in line to use the only phone in the area. Letters took four weeks to arrive. The muriquis were different—they weren’t typical primates. In 1994 I published a paper called “Myth of the Typical Primate,” which offered a new perspective on primates in general.

Among muriquis, there is no size difference between the sexes. Males can’t threaten females because they aren’t bigger than them

What makes the muriqui atypical?

An animal’s diet is calculated based on the proportion of each food type it eats. So if the largest proportion of their diet was leaves, they would be classed as folivores. I realized that leaves were important to their diet, but supplementary, because their entire behavior was focused on what they preferred to eat: fruits and flowers. This changed our interpretation of how diet should be used to interpret behavior.

Did anything else differ to theoretical predictions?

When I was 19 and doing my undergraduate degree, I spent six months in Africa participating in a study on baboons. Because of that experience, I had an idea of what a typical primate should be like. Male baboons are twice the size of females, they have huge canines, are dominant, and have hierarchies. It is the males that migrate between groups looking for a mate to reproduce with. Muriquis, meanwhile, are monomorphic—there is no size difference between the sexes. Males cannot threaten females because they aren’t bigger. They have no hierarchy, they don’t fight, aggression between group members is very low compared to other primates. They hug a lot. Their sexual behavior is very open: males and females mate in front of each other, or one female mates with several males in a row. If she doesn’t want another male, she leaves—the males don’t chase after her. They’re very calm. With other primates, it’s the male leader who decides who to mate with and when.

Do you know why they are so different to other primates?

To this day, I still can’t say for sure. We understand a lot about their biology, diet, and social and sexual behavior. We have collected their feces and extracted estrogen, progesterone, and other hormones to understand their reproductive biology. We determined that females have 21-day cycles and gestation lasts 7.2 months. We have also seen that females leave their birth group at the beginning of puberty, before they start mating, and take some time to integrate into other groups. Among males, testosterone levels don’t vary much. We’ve done paternity analyses using feces and monitored changes in the population and its demography.

What changes occurred in the population you followed?

When I started, there were two groups of about 50 individuals. I focused on the main group, but after about 20 years we decided to study the entire population. Now there are five groups. Between 1983 and 2015, the population grew from 50 individuals to 356, and it’s still recovering. One of the changes we observed is that the animals always stick together when the group is small, but they spread out more when the size of the group increases and competition for food grows, because they can’t all fit in the same trees. As the population grew and the available forest diminished, they started to use the ground more, at first for eating and then for resting. This behavior spread within a group and between different groups—it was probably an adaptive response to the limited space.

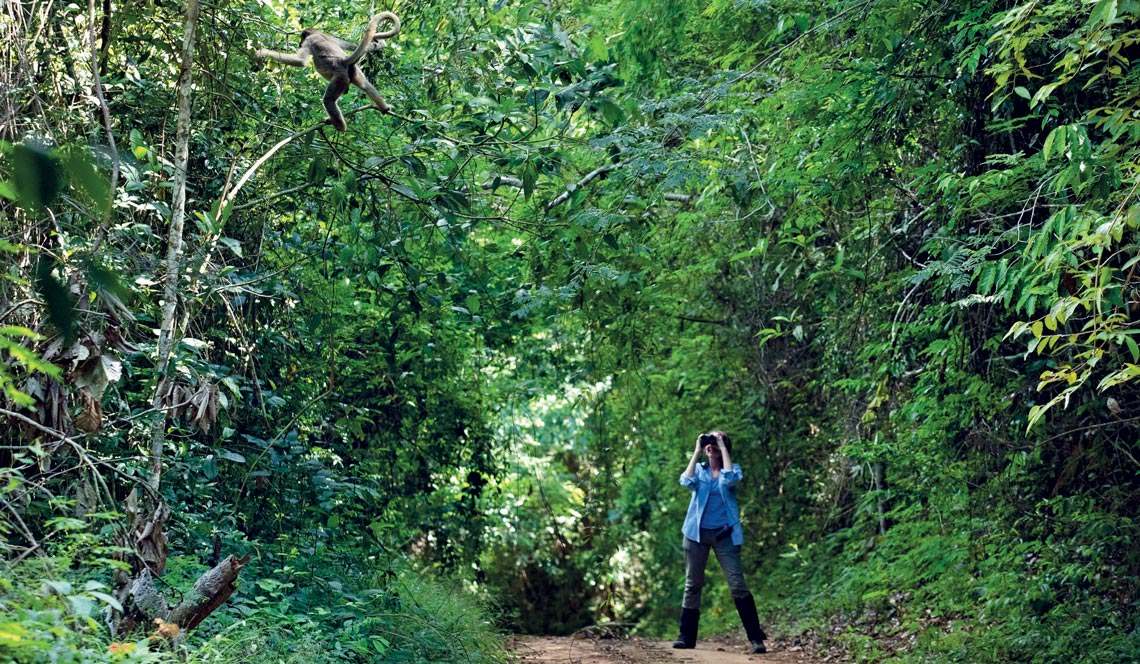

Personal archiveStrier has been watching muriquis from the trails of the Caratinga reserve for 40 yearsPersonal archive

Do they face other any other challenges, besides deforestation?

Fortunately, a lot of forest has been regenerated, despite deforestation. But the years 2014 and 2015 were very dry in Brazil. There was almost an electricity crisis because the dams ran out of water. The forest too. The muriquis dug in the mud to find water. In 2016 the rains returned, but a wave of yellow fever killed more than 30 individuals—10% of the population—in six months. The muriquis experienced mortality like never before. Other species from the areas I study, like howler monkeys and marmosets, have also disappeared. Unfortunately, the population has continued to dwindle in the last five years. I don’t know why. We’re now at about 240 individuals, which is still five times what it was when I started. The population growth was a direct result of favorable demographic conditions: births every three years, with more females being born, and low mortality rates. Also, the owner of the farm where the Caratinga reserve is located, Feliciano Miguel Abdala [1908–2000], banned hunting and helped preserve the forest. This made the muriquis safe. The forest was protected and the population was able to grow. After Feliciano died, his family created an RPPN [Private Natural Heritage Reserve] named in his honor.

In October 2021, you published an article about the muriquis’ limit of resilience. What is their limit?

We still don’t know what this species’ limits of resilience are. What the muriquis are demonstrating is that given a chance, they are capable of adjusting their behavior and adapting to challenging conditions. But that doesn’t mean they’re safe, we have to pay attention to these changes and gather more information. Together with my colleagues and students, I am monitoring how the muriquis in Caratinga adapt over time.

Do you have a personal relationship with the muriquis?

The muriquis from Caratinga are like people I know, although less so nowadays because the last individual of the original group died a few years ago; they can live for over 40 years. Now, their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren are there. The animals were my companions for many years and I have no doubt that they recognized me. Many other researchers have visited over the last few decades, but when I go into the forest with a visitor, they try to hug me and threaten the other person.

What was it like when you first went to the interior of Minas Gerais to begin your research?

The first time, I just went to visit. Later I returned with funding and a research visa during my PhD. Brazil has a system that requires foreign researchers to have a counterpart—a local collaborator. In my case, this person was Célio Valle, a professor from UFMG [Federal University of Minas Gerais], now retired. He welcomed me into his laboratory and made it easy for me to get to know people in the area, such as Adelmar Coimbra Filho [1924–2016], the first director of the Primatology Center in Rio de Janeiro. Whenever I went to Rio, I stopped by his house. He and others who pioneered the conservation of the Atlantic Forest made me feel so welcome and helped me a lot. In 1983, I met Sergio Lucena at the research base in Caratinga. I was studying the muriquis for my PhD and he was doing a master’s on howler monkeys. At that time, my counterpart was Gustavo Fonseca, who was also a professor at UFMG, but he later moved to the US and worked at Conservation International. He’s now at the GEF [Global Environment Facility]. So then Sérgio became my counterpart, and he still is to this day. More recently, we included Fabiano de Melo as a second collaborator to help with the workload, in addition to my other colleagues, Carla de Borba Possamai and Fernanda Tabacow, who started as fellows on the project in 2001 and 2005. This system gave me the opportunity to collaborate with primatology and environmental conservation experts in Brazil and I felt part of a larger group from the very beginning. It was a long-term project—I secured the funding, but I couldn’t have done anything without my Brazilian colleagues.

A long-term study lets you see which behaviors are more rigid and which are more flexible

And the locals?

They always treated me very well. In the early 1980s, most Brazilians had never met an American, and as a single, 23-year-old woman who came from another country to live alone in the forest for 14 months, I certainly attracted some attention. Many residents came to the research base just to see me; one woman wanted to touch my hair, even though there’s nothing special about it. Feliciano came by every day to check on me, but I was usually in the forest working. Over time I started making friends, I went to parties, baptisms, weddings. I even learned to drink cachaça! Some of my best friends are Brazilians.

What are your plans now?

We want to get local people and schools from the regions where we work more involved, to maintain communication networks between children and get people interested in preserving and monitoring the areas where primates live. We recently carried out a citizen science project with Marcello Nery, president of MIB [Muriqui Biodiversity Institute, a nongovernmental organization based in Caratinga], to learn more about primates in the reserve. We made a calendar with photos of the four monkey species that live in the region and asked residents to write down if they saw or heard any of them. We then discovered that we didn’t even need to make monthly visits to collect the data, because people could tell us what they saw via WhatsApp.

Does the unified theory of behavioral ecology mean we can study insects and primates in the same way?

No, you can’t study different animals in the same way. A good study needs to use a methodology designed for the specific species, conditions, and research questions. The principles have a certain continuity because they come from kin selection, evolutionary ecology, and sociobiology. At least among social species such as primates and ants, there is much greater variation in behavior than expected. But it is not possible to compare concepts of individuality between primates, mice, ants, or other species that do not live as long as primates. The lives of mice and ants can be complex, but primates have more opportunities to learn and respond to novelty. It’s these aspects of primates, related to their lifelong histories and cognitive abilities, that make them as interesting as other long-living animals, such as elephants. This is one of the major contributions of our research on the behavior of muriquis. With a long-term study, we are able to see which behavioral aspects are more rigid and which are more flexible. This helps a lot when planning population management. Along with the greater understanding of behavioral flexibility that we have gained over the years has come the recognition that in most cases, we are studying animals that are not in their original environments—their habitats have been altered.

Altered or degraded?

When I told my colleagues in the US that I was going to study muriquis in Caratinga, they asked me, “Are you sure? You’re going to study animals somewhere that has been very disturbed, to the point that it’s now just a fragment. How are you going to understand their evolutionary behavior?” The northern muriquis came from the old Atlantic Forest in the south of Bahia, Espírito Santo, and Minas Gerais, which is now highly fragmented and deforested. This means they now live closer to farms and cities, as do the southern muriquis [Brachyteles arachnoides], and are thus at greater risk of being killed by humans. But this problem is faced by primates all over the world. We have to be careful with our observations because we don’t know exactly what the original conditions were like. That’s very humbling for a scientist, admitting that we don’t know what to expect. Now—and this is since quite recently—we can say with certainty that the northern muriqui and the southern muriqui are different species. Genetic analyses show differences between the two species, and they may have emerged some 2 million years apart. It’s similar to the genetic difference between the chimpanzee and the bonobo in Africa.

Personal archiveWith Feliciano Abdala in Caratinga, 1988Personal archive

Do you have students permanently studying muriquis?

Yes. I have received funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Geographic Society, the Margot Marsh Biodiversity Foundation, several zoological societies, the University of Wisconsin–Madison itself, the CNPq [Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development] and CAPES [Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education] not only to bring over students from the US, but also to train and qualify Brazilian students, based on the fact that the muriquis represent a part of Brazil’s heritage. Many biologists here wanted to study them but weren’t able to do so due to a lack of funding or training. Every year two to four students join my study to collect data for their master’s degrees and later carry out their own scientific research to support conservation. Contributing in this way gives me immense satisfaction. The muriquis have helped train and educate the next generation of scientists. Those who started with me on fellowships are now doing their own studies in other places, such as the Caparaó National Park [on the border between the states of Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais], Paraná, and now, under the guidance of Fabiano, Carla, and myself, in São Francisco Xavier.

Did your work at the International Primatology Society contribute to your research in Brazil?

My term was supposed to end in August 2020, but because of COVID-19, our conference [at which the president of the society is changed] was postponed. As a result, I presided over the International Primatology Society for longer than any previous president: five-and-a-half years. At the same time, Leandro Jerusalinsky, a Brazilian, was president of SLAPRIM (the Latin American Society of Primatology). We worked closely and had a good relationship because we’ve known each other for a long time. Brazilian primatologists therefore naturally had a lot of opportunities at the international society, because they felt comfortable getting in touch with me. Now, one of the society’s vice presidents and its general secretary are Brazilian. I was able to help by giving a bigger platform to people who were already very active in the field, giving them recognition and promoting their work. We have a spectacular team of Brazilians, I have no doubt that one of them will be president in the next few years. Brazilians are renowned in international primatology.

In 2020 you received an important award in Atlantic Forest conservation: the Muriqui Prize. It took a while, didn’t it?

I thought so too! Just kidding. Of the previous winners who I know, they all deserved it, so I can’t say I should have won it sooner. It’s rare for a foreigner to win, so that made me feel even more grateful. It made me feel like my Brazilian colleagues are still taking care of me. I felt very honored to receive the award, which is a result of the long-term partnerships I have forged with my Brazilian colleagues.

Have you ever felt like going back to Africa, where you had your first primatology experience?

Not to do research. The only time I went back to Africa was a trip to Kenya a few years ago to speak at a conference. I told the audience I had been there as a student when I was 19 and never thought I would return, so many years later, as president of the International Primatology Society. When I was doing my PhD, I applied for funding to study primates in Asia. It was very competitive, and I was offered a 14-month scholarship with free language lessons included, but I chose to return to Brazil and continue studying muriquis instead. I was “married” to the muriquis and never thought about leaving. Sometimes I feel like I have two lives, one here and one in the US. I feel more alive here, but there I teach and have day-to-day responsibilities at the university. Maybe part of the reason I feel more alive here is because right now it’s summer here, warm and sunny, while it’s zero degrees in my home city.