Léo RamosIn September of this year, the Economics section of some newspapers carried an interesting piece of news on the Vale mining company, Brazil’s largest private-sector enterprise. The information was that the company was planning to create R&D units as part of the ITV Vale, Vale Technology Institute, in three different states. The project has been nursed by the company for quite a while. Vale already has three technology centers, of which two are in Minas Gerais state and the third is in Canada. They focus on providing immediate and short-term solutions. The new units, however, will be different: their mission will be to think about Vale’s long-term future, and to stay in tune with new business trends that often drive the creation or demise of companies.

Léo RamosIn September of this year, the Economics section of some newspapers carried an interesting piece of news on the Vale mining company, Brazil’s largest private-sector enterprise. The information was that the company was planning to create R&D units as part of the ITV Vale, Vale Technology Institute, in three different states. The project has been nursed by the company for quite a while. Vale already has three technology centers, of which two are in Minas Gerais state and the third is in Canada. They focus on providing immediate and short-term solutions. The new units, however, will be different: their mission will be to think about Vale’s long-term future, and to stay in tune with new business trends that often drive the creation or demise of companies.

For an enterprise such as Vale, it is crucial to be aware of and to anticipate trends. Established in 1942 and privatized in 1997, the firm has an estimated market value of US$145 billion. In the third quarter of 2010, its net income amounted to R$10.5 billion. It is the world’s second largest mining company, preceded only by BHP Billiton, an Australian concern. Vale’s businesses involve not only mining, but also logistics (railroads, ports and coastal navigation, fertilizers and hydroelectric power plants). Vale alone consumes 4.5 percent of all of Brazil’s power. Its iron ore production, the company’s main product, reached 238 million metric tons in 2009. Today, the company has over 100 thousand employees and is active in 35 countries. With all this muscle, any Vale gesture is bound to have major repercussions.

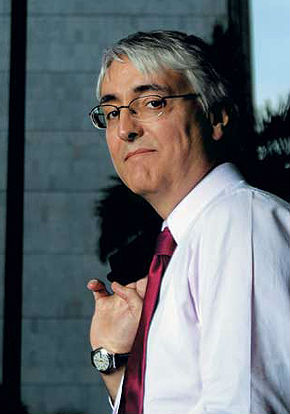

Innovation in strategic areas is therefore a matter of survival. ITV’s operations are to extend beyond the technology centers that are already running. The target is to provide innovation education and research in fields such as mining, sustainable development and renewable energy. The model it plans to follow is that of MIT (the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), a traditional American institution that emphasizes transferring technology to firms and educating entrepreneurs. To get ITV up and running, the company hired Luiz Eugênio Mello, a neurophysiologist and former dean of undergraduate studies at the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp).

Mello is a productive researcher who has always kept one foot in neuroscience research and the other in science and technology management. A senior professor at Unifesp, he was one of the joint coordinators of the FAPESP science office (2003-2006) and is ranked a level 1A researcher by CNPq (the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development). As dean of undergraduate studies from 2005 to 2008, he played a major role in the university’s expansion: 4 new campuses were created, along with 18 new courses, while the number of student places shot up from 1,200 to 3,800.

In 2008, he moved from São Paulo to Rio de Janeiro (where Vale’s headquarters are located) with the mission of making ITV come true. Two years later, he is achieving this. The institution’s units in the cities of Belém and of Ouro Preto are to go into operation in the first half of 2012, on their own premises, and the São José do Rio Preto unit will open in the second half of 2012. The mining company’s investment in the institute, a longstanding wish of its CEO, Roger Agnelli, exceeds US$350 million over the 2009-2011 period. “Getting a project of this magnitude up and running in an enterprise like Vale, in a country like Brazil, is a unique opportunity”, says Mello, explaining why he decided to undertake this challenge. Once a week, he continues to provide guidance for graduate students and still finds time to write scientific articles. Below, he explains the ITV project in detail.

Where did Vale start to use more advanced technology in its mining activity?

The best way to talk about this is from an historical perspective. Vale was established in 1942 in Itabira, Minas Gerais state, where there was an outstanding deposit of hematite. The company grew by working on iron ore at that site. By the early 1960s, technical difficulties started appearing. Hematite was becoming scarce and the ore that contained iron, in a different form, but that was available at the time, was itabirite, with less iron. Implementing the use of high intensity magnetic separators allowed Vale to process itabirite. This innovative process is seen as its first major technological leap, which led to the creation of the firm’s first R&D center, in the town of Santa Luzia, halfway between Itabira and Belo Horizonte. Even back then, it was already evident that they had to use more technology. It was a time when one could open a mine by merely asking for a license after producing a mining plan.

And what has changed?

Today, one must have an opening and a closing plan for the mine. The environmental regulations are of another order of magnitude. When you begin an operation of this kind, you may already have forecast that the mine will be good for 40, 50 or more years of exploration. Itabira has been active for 68 years. There was a time when people thought that mining there had already reached its end, but they started mining other ores and even waste, with other features, minerals which had been regarded as unsuitable in the past but can be used today. All of this was technical and technological progress. Roger Agnelli, Vale’s CEO, often says that the world is moving out of a market economy and into a green economy, and in this new set of circumstances it will be necessary to have a license for operating, granted not only by regulatory agencies, which determine what can be done today, but also by the nearby population, the state, the country and, ultimately, the world.

Is it at this point that technology becomes an ally?

It is a great ally, by predicting problems. When oil exploration first started in a Texas oil well, the oil was almost at the surface. Today, one has to drill seven kilometers down to find anything. Copper has to be drawn up from a depth of 700 meters. In South Africa, there are mines almost 3 thousand meters deep. However, it has to be worthwhile. One spends a lot of power hoisting the ore up and there are huge logistical difficulties involved. Exploiting gold under these sorts of circumstances might be justifiable. However, when it comes to other ores, technical and financial limitations start at about 700 or 800 meters.

Has Vale always worked with iron ore?

It started with iron ore in Itabira and then expanded into other minerals. Hematite and itabirite are iron ores, but today Vale also mines nickel, copper and coal; it has become a minority player in the bauxite, alumina and aluminum business, and has attempted to mine diamonds. Fertilizers are the company’s new challenge. They are split into at least two of Vale’s main areas, phosphates and potassium.

Why fertilizers?

The rationale is the following: what drives the iron market is construction and the auto industry, principally, along with a few other areas. What if people stop buying cars or they start being made out of different materials? This would create a different scenario for Vale. What if people stop living or working in skyscrapers and only use houses that don’t require iron and are built differently? This too would lead to a different scenario. Vale’s risk in working only with iron ore is great. The company decided to diversify in terms of minerals and invested in nickel, by purchasing the Canadian mining concern Inco, in 2006. And we also opted for fertilizers, which are driven by food. It’s a different type of business. The diversification strategy is important.

Does ITV encompass all these lines?

The institute has three dimensions. It had already been proposed back in 2006 and even then, this name, Vale Technology Institute, already existed. The internal diagnosis produced at that time identified a set of theme areas. The first is the environmental and biodiversity one; the second is mining strictly speaking, and the third concerns energy. These areas are considered critical for the company’s development.

Energy in the sense of electric energy?

Energy in general terms, particularly renewable energy. At present, biofuel is what looks like the most interesting option. Vale is going to produce palm oil, the raw material for biodiesel, as from 2014, in the Vale do Acará and Baixo Tocantins regions, which encompass seven Pará state municipalities. Palm can produce as much as two thousand liters of biodiesel per plantation hectare. Vale consumes billions of liters of diesel a year. In the case of Pará, we created the Bio Vale Consortium together with the company Biopalma. This consortium will be the largest palm oil producer in the American continent and the investment in the project amounts to US$500 million. With this partnership, Vale plans to use part of the palm oil production to make B20 biodiesel (a blend of 80 percent common diesel and 20 percent biodiesel), a fuel that it plans to use in all the Carajás railroad locomotives and in the large machinery and equipment in its mines in the region.

LÉO RAMOSDoes ITV really plan to follow the MIT model?

LÉO RAMOSDoes ITV really plan to follow the MIT model?

We have two great university models in the world and both are in Boston, USA. One is Harvard, the other is MIT. Harvard is an academic university par excellence, with many published articles, scientists with a great reputation, etc. MIT was born with a different aim: to create quality science while doing everything possible to transfer this to the corporate sector. The MIT model has been highly successful. As has the Harvard one, inspired by the English universities, such as Cambridge and Oxford. However, Harvard strengthened its administration and business management side alot. The Harvard Business School is the most visible element of the coming together of academia and entrepreneurship. MIT, however, does this based on its science, even though it also helps to educate people and entrepreneurs, while Harvard seems to do such things more for an external audience, rather than based on its science.

Was it this MIT practice that inspired Vale?

This goes back to a phrase of Roger Agnelli himself, when he said he wanted to have the ITA [Brazil’s Aeronautics Technology Institute] of mining. ITA was partly the result of MIT professors – its first dean, Richard Smith, came from MIT. Roger, on the other hand, speaks of having Vale’s MIT. For a long time, the company has maintained a training program for its executives at MIT. I believe that this Vale aspiration is due, in part, to the notion that when we look at Brazilian universities, this facet of the American institutes is precisely what’s missing. The overflow beyond their boundaries, the interaction with the private sector, the corporate sector. But it’s still a building process, something that we will take decades to establish.

But is it a real model to follow?

It’s real. And I think it could be very successful here because present day Brazil is not the present day USA. I think that if Vale were a company headquartered in the United States, it might not have to set up this institute in this format. It only makes sense here because Brazil, in many ways, is like the United States was several decades ago. The number of electrical appliances in the homes, the population’s level of literacy, the percentage of young people aged 18 to 24 enrolled in higher education, the number of cars – Brazil today, regarding several such parameters, is comparable to the United States in the 1940s and 1950s. I think that there’s a parallel between the two countries. We are in the process of extending ourselves, of growing in stages.

Is ITV to operate according to a model that is also unconventional for Brazil today, an open innovation system? [in which the flow of information among several agents allows ideas to be exploited better even if not by the people who came up with them?

Vale is already working with open innovation. It is important to mention that the company has and will continue to have other R&D centers conducting research focused on immediate needs. The center that I mentioned at the start, in Santa Luzia, does that and it will continue to exist, like the other two, the Iron Products Technology Center, also in Minas Gerais, plus the one in Canada. They are fundamental for the company’s success on a daily basis.

Are these centers similar to those that IBM announced it is planning to set up in Brazil?

Yes, precisely. I think that IBM, at its United States headquarters, is positioning itself in a way that is similar to that of a currently small set of firms in the world, with long-term R&D, such as HP, Siemens, GE, and Dupont, for instance. GE is also setting up a center in Brazil. Most of the companies work only on a short-term basis, and seek their solutions outside, through agreements with universities. Now, Vale has become one of the few firms in the world, along with the other ones already mentioned, to also have a long-term R&D group.

How are the three planned ITV units to operate?

In the first, in Belém, we will work with the Federal University of Pará, the Rural University of Amazonia, the company Embrapa Ocidental and the Goeldi Museum, all of them institutions established there and they are privileged partners, as being physically near makes collaboration easier. This does not exclude partnering with other institutions. We have already signed an agreement with MIT, which is to send professors over there, as well as with Brazilian educators and students, who will also go to this US institute.

What is the focus of this unit?

Sustainable development and entrepreneurship. This cooperation agreement is important, the first of this kind that MIT enters into with a corporate institution.

And what exactly will you study, within the context of this theme?

For me, the environment is the most important area in this set. The two countries from where most of the iron ore is extracted and exported are Brazil and Australia. Australia is the most developed country when it comes to mining science and technology. However, over there, they mine in the desert. We do that in the tropical rainforest. On one hand, we have an effect on the forest; on the other, it rains heavily; there are a number of conditions that are different, that call for different technologies and have different environmental impact. What the Australians research is not necessarily what is applicable over here.

Where will the other two ITV campuses be?

One will be in Ouro Preto, in Minas Gerais state, and will focus on mining. The other will be in São José dos Campos, São Paulo state, and will focus on the energy area. Regarding both the Belém and the Ouro Preto centers, we have the architectural project ready. We’re making progress on their engineering details and are hiring their directors. Then we will hire the researchers.

How many researchers will ITV have?

About 50 to 60 at each of the three units, all of them with PhDs, to be hired by ITV with a career plan, salary and benefits. They are to research thematic lines that are being determined by means of a series of workshops. Besides these PhDs, we will have an added 100 to 120 post-doctors in the three units. In other words, we will have post-graduate teaching offering formal degree courses, accredited by Capes, with masters, PhDs, technicians and the administrative body. Overall, each unit will have some 350 to 400 people. A public call was released jointly with FAPESP, in São Paulo, with Fapemig, in Minas Gerais, and with Fapespa, in Pará. The agreements with the research aid institutions (FAPs), signed in 2009, will help us to get other researchers from these states working on a part of the projects jointly with the ITV researchers. There are R$120 million involved in the project.

Broken down how?

In São Paulo and Minas Gerais, the ratio is one to one: R$20 million from Vale, R$20 million from the state FAP. In Pará, where the FAP is still being consolidated, there are also R$40 million overall, but only R$8 million from the foundation and R$32 from Vale. Overall, Vale will provide R$72 million and the FAPs, R$48 million. The agreement covers four years, the time span of a FAPESP thematic project.

LÉO RAMOSWhat do the projects involve?

LÉO RAMOSWhat do the projects involve?

In these cases, they can involve grants, equipment, defrayment, and some of them might involve construction. Vale was already planning to invest more or less this amount of money before I joined the company. At the end of the day, it’s a win-win situation. Previously, Vale’s projects were run like this: if there was a port that should be more efficient, the company invested in it. The Tubarão one, in Espírito Santo state, is the world’s most efficient grain port. And it only became exemplary because the company hired research projects from universities, more specifically from USP, and the proposals worked. However, this won’t solve the future. What about problems 10 or 20 years down the road? The public tenders currently under way in conjunction with the FAPs are for that. We want to look at themes that are far in the future and that have the chance of changing Vale’s business. One example I like to use is ceramic engines. About 20 or 30 years ago, there was a promise in the air that ceramic engines would bring about a major revolution. There would no longer be car engines made out of iron; everything would be ceramic because durability would be far greater. However, this didn’t come true, though I don’t know why. However, what if it had? Vale must be prepared. The people that will look at things for the firm from this viewpoint will be ITV. It will have to be attuned to the world and try to foresee possibilities that might change our business.

Will ITV have people from all areas, or only those connected with each unit’s specific theme?

We’ll have a wide range of researchers, even in the humanities. People who study law, anthropology and sociology, some of the areas that are important for us. There are studies that are more remote, multidisciplinary. What will Vale be like in 50 or 100 years? I don’t know, but no enterprise wants to die. Vale hopes to be, in 2014, not only the largest mining concern on Earth but also the best. However, what about 2024? And in 2034? At that time, with ITV results, it should continue to be the biggest and the best because it will have looked into the future before the others and will have foreseen the world’s needs 20 or 30 years hence.

How important is the São José dos Campos unit in this strategy?

It is important for several reasons. One is that it’s in São Paulo, the base of renewable energy production in Brazil, if we consider ethanol. We also have 50 percent of the technology and science produced in the country in this state. There is FAPESP, a strong source of investment in research. On the other hand, in São José dos Campos, we have ITA and Inpe [the National Space Research Institute], two important institutions. We already have a partnering agreement with ITA in the company VSE Vale Soluções em Energia [Vale Energy Solutions] to make engines and turbines to run on biofuel, and because the company needs distributed power generation. VSE is two years old and is an initiative partnered by BNDES [Brazil’s National Social and Economic Development Bank], which is financing 48 percent, and Vale, with 52 percent.

Is the education of entrepreneurs planned in graduate courses?

Universities are the main place where innovation appears in Brazil and researchers, generally speaking, have difficulty leaving academia to become entrepreneurs. In the institute, we plan to have people with this profile who are willing to take risks.

Let’s talk about your own research. What are your patents about?

The two patents were granted in Brazil, China, Canada, the European Community, Korea, Japan and Mexico. They concern a treatment for epilepsy. There is one epileptic condition that is called post-traumatic. If you suffer major cranial-encephalic trauma, like any major blow that causes you to lose consciousness and perforates the skull, there is the risk of developing epilepsy. The greater the lesion, the greater the risk. Of course, it also depends on the area of the nervous system that was affected. At present, there is no therapeutic intervention capable of reducing the risk of developing epilepsy after a strong blow on the head. I started looking into this through the scientific initiation project of Cristina Massant, with a FAPESP grant. The patent concerns using scopolamine, a drug that can also be used as a truth serum. Despite its hallucinogenic potential, it is used among healthy normal human volunteers, to imitate the conditions of Alzheimer’s disease. It causes temporary memory loss. It’s the same drug used in the “good night Cinderella” trick. One of the companies that could have invested in it as a medical drug was not interested because of its illicit use potential. What I witnessed in animals under laboratory conditions is that if the drug is used for the right amount of time, few develop epilepsy. And, when they do, the crises are weaker. As the industry was resistant, I looked for another drug with a similar clinical use, but without the hallucinogenic potential. I turned to bipyridine, used to treat Parkinson’s disease, but with a far lower dose and in different conditions. I showed that among laboratory animals and on a preliminary basis among humans, if one uses bipyridine after a very strong blow on the head, during a highly specific period, one can avoid epilepsy. We also patented this drug.

So the mechanisms of the two drugs are the same?

It’s the same. And therefore, as the two affect the same receptor, I, in the second case, also patented the drug class that acts on this receptor. It is a broader patent. Even so, I haven’t managed to work with it and no industry has shown any interest yet.

Have the new activities reduced your academic production?

I’m short of time, but this year I managed to publish seven articles on my own or in collaboration with other researchers, all on neuroscience. Also this year, three doctoral theses for which I was the chief advisor were defended. Another two theses and one master’s degree dissertation are still to be defended in 2010.

Where do you find time?

I wake up at five in the morning, write e-mails and solve pending issues. When I’m in São Paulo, I set meetings for the end or the beginning of the day, as well as on weekends… It’s the only way to make time.

And how did a neuroscientist become the head of the technology institute of a mining company?

I came to a meeting with Roger in August 2008, on a Friday. At the time, one could already see signs of the impending crisis, even though the world seemed healthy enough. And Roger was always quoted in the press saying that he needed personnel such as solderers and engineers, but couldn’t find them. I had become the Dean of Undergraduate Studies of Unifesp in 2005 and under the Reuni [Program for Supporting the Restructuring and Expansion of Federal Universities], we had created four campuses and 18 new undergraduate courses. During this expansion, there was a possibility of opening a campus in the city of Osasco, and one of the ideas was that it should focus on engineering. We established a commission to study the issue and realized that Vale might be a special partner for Unifesp. The university has excellent indicators at several levels and I believed that it made sense to try to establish strong collaboration between the firm that needed well trained engineers and a new engineering school. That is what I had come to talk to Roger about. I insisted for a year until I finally managed to get a meeting, because of his schedule. In the room, were the executive director of human resources, Carla Grasso and Roger. I peddled my wares for half an hour. When I was done, he said, “Great, that’s all fine, but I have a dream. I want to set up the Vale Technology Institute, something akin to MIT. I find this extremely important, a legacy that Vale must give Brazil. Will you help me?” I said sure, I knew lots of good people and returned to my subject. He started to talk about the institute again, while I went back to the courses that I wanted to create, but the third time round he said: “You’re missing the point, I’m talking about you working here”. I hadn’t gone there to be recruited and I wasn’t looking for a job. However, I was absolutely fascinated by the possibility of leading such a grandiose and important project as this. The next day, a Saturday, I woke up at four in the morning, already assembling the institute. What it would be like, what researchers it would have and in what way; I went to take a look at Google Earth to see where the Belém unit might be established. Being invited to be part of a project of this magnitude in a company like Vale, in a country like Brazil, and at the current moment of the world is a unique opportunity. As well as a world-sized responsibility.