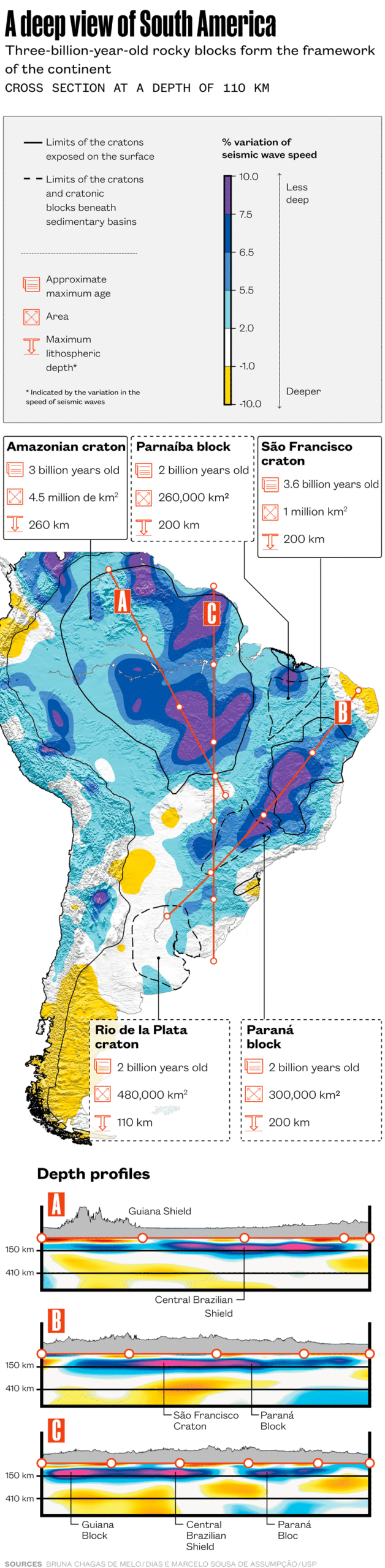

Tomography techniques, like those used to examine inside the human body, have revealed an unexpected fragmentation of the layers up to 600 kilometers (km) below the earth’s surface. The images led to the redefinition of boundaries, revealed deep structures about which only indications had previously existed, and reinforced the idea that surface mapping is insufficient for outlining the rocky skeleton of South America.

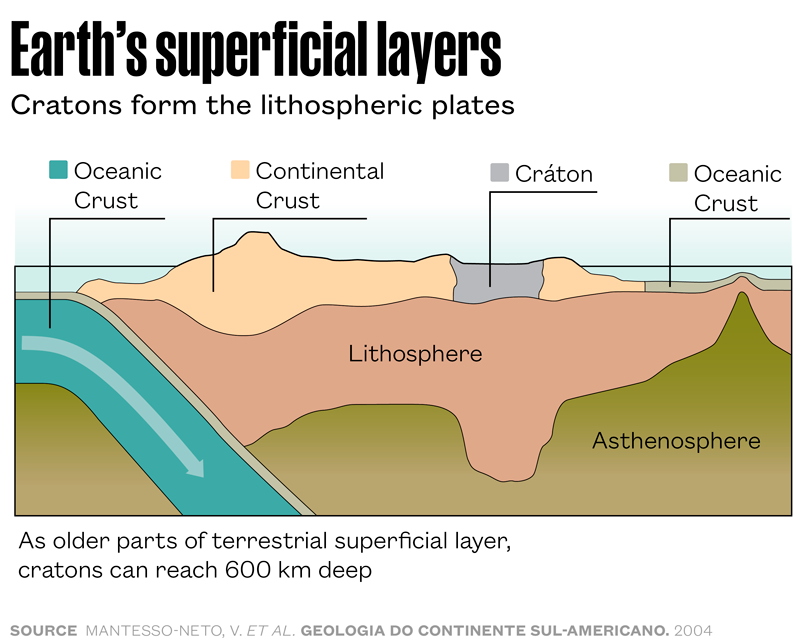

The images at different depths are produced by analyzing different types of waves generated by earthquakes, also known as seismic tremors. Initially captured by devices called seismographs, they cross the interior of the earth at speeds which vary according to the density of the rocks: the speed is faster where the lithosphere—the solid outermost layer of the earth—is thicker, and cold and slower where it is thinner and hot. It is a way of seeing the boundaries of what are known as cratons, blocks of rock that extend for hundreds and thousands of kilometers, sometimes covered by sedimentary rocks or soil. Generally formed between 1 billion and 2 billion years ago, when the earth was still very hot, they form the framework of the geological structure of the continents, around which other rocky structures accumulate (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 188).

Serra do Cipó National ParkThe Espinhaço mountain range, which extends for around 1000 km in the states of Minas Gerais and Bahia, marks the eastern edge of the São Francisco cratonSerra do Cipó National Park

In one of the most recent and comprehensive surveys, described in an article published in November in the journal Gondwana Research, physician Bruna Chagas de Melo, from Belo Horizonte, and colleagues from the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in Ireland, showed that the Amazonian craton, until now seen as a single, oval structure, through the middle of which flows the Amazon River, may actually be made up of two parts, separated laterally at about 200 km below the surface.

Also, in accordance with this study, the boundaries of another craton, the São Francisco craton, are broader and located more to the southwest than shown by previous mapping. Three ancient units of the continental geological structure, proposed by geologist Umberto Cordani, from the Institute of Geosciences of the University of São Paulo (IGC-USP), in the early 1980s, gained clearer contours. They are the Rio de la Plata craton, which covers parts of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Uruguay, and Argentina, and two cratonic blocks, named because they are covered by sedimentary basins: the Parnaíba, in Piauí, and the Paraná (or Paranapanema), located beneath the Paraná River basin in the states of São Paulo and Mato Gross do Sul.

An increased understanding of this ancient rocky structure—at greater depths—helps to detail both the geological and biological evolution of the continent. As the Andes mountain range formed to the west, it reversed the flow of the rivers, shaped the surface, and blocked moisture from the Atlantic, favoring the emergence of new species of plants and animals, especially in the Amazon region (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 334). It also helps explain the origin of mineral provinces, including the areas most likely to contain diamonds, which form at depths of at least 150 km, and reinforces the history of landscapes, such as those associated with volcanic activity, which occurs in regions with a thinner lithosphere.

Particularly to the east of the Amazon and south of Pará, almost 2 billion years ago, there were dozens of volcanoes and rivers of lava flowing over the surface (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 81, 174, 250). In more recent times, magma also rose in the regions occupied by Marajó Island, in Pará, and Dourados, in Mato Gross do Sul, and there are magma channels, although inactive, beneath the archipelagos of Fernando de Noronha, Trindade, and Martin Vaz.

There are still clear signs of magmatism, such as the Pico de Cabugi Peak, in Rio Grande do Norte, which has a height of 590 m and preserves the shape of a volcano, and other more subtle examples. The municipality of Poços de Caldas, in Minas Gerais, for example, is expanding on the edge of a volcanic crater, through which magma rose around 60 million years ago.

“The magma was only able to rise because the lithosphere was, and still is, thinner in this region, between the São Francisco craton and the Paranapanema block. A thinner lithosphere means that the asthenosphere, the hottest layer directly below the lithosphere, was shallower, enabling the fusion of rocks, at a depth of between 100 and 200 km,” comments physicist Marcelo de Sousa Assumpção, of the Institute of Energy and Environment (IEE) at USP and coauthor of the article in Gondwana Research. He has been studying the movements of the earth’s crust since the mid-1970s (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 53 and 256), was Melo’s master’s degree advisor, and helped her take her PhD in one of the major international geophysics research centers, in Ireland.

Melo arrived in Dublin in December 2018 with the intention of applying the method that her advisor, Russian geophysicist Sergei Lebedev, had developed to analyze large quantities of seismic data—records of the waves created by earthquakes. In just a few months, she gathered information on approximately 970,000 seismic waves, resulting from around 300,000 tremors, recorded by 9,259 seismographic stations worldwide, including those in Brazil, collected since 1994, at depths of up to 600 km.

“It’s a formidable amount of data, I’ve never seen anything like it,” admires geologist Reinhardt Adolfo Fuck, professor emeritus at the University of Brasília (UnB), who has been studying the evolution of the lithosphere in Brazil for 50 years (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 122). “They took great care in making the necessary corrections and excluding what needed to be discarded.”

Six months later, at a congress in Vienna, Austria, Melo presented the first evidence that the Amazonian craton could be two, one to the north and another to the south of the Amazon River. “I didn’t see the entire block at any depth,” she commented in November, reviewing her work.

With another seismic wave analysis methodology, fewer data—112 tremors and 1,311 seismic stations—and also a lower maximum depth, of 500 km, geophysicist Caio Ciardelli had already raised the possibility that the deeper areas of each side of the craton had thinned, due to movements within the earth’s interior, and had broken, as detailed in his PhD, completed in 2021 at USP’s Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics, and Atmospheric Sciences (IAG), and in an article from January 2022 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. “Other seismotomography results varied, showing either continuity or separation,” says Assumpção, who supervised Ciardelli’s PhD and is currently undertaking a postdoctoral fellowship at Northwestern University in the USA. “Bruna settled the debate, by showing there was a thinning or wear along the Amazon River.”

Marcelo Rocha, a physicist from UnB, who has been working with tomography of the lithosphere since 2001, disagrees. “She didn’t settle it. Any conclusion is still premature, because we have little data on the region, one of the least studied in Brazil. There are few seismographic stations there, and they are 800 or 1,000 km apart,” he says. “In fact, the Amazonian craton is neither one nor two, but many, with different ages, ranging from 3.1 billion to 1 billion years.” The fact that there are rocks with the same ages on each side, as verified decades ago by geologists, suggests that the craton must have once been a single block, that, at some point, split in two, at least on the surface, opening a valley that would later be occupied by the Amazon River.