Beginning next year, new collections from two important Brazilian intellectuals will be open to the public. The personal archives of economist Celso Furtado (1920–2004) will be available at the Brazilian Studies Institute at the University of São Paulo (IEB-USP), while the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation (FUNDAJ) in Recife is preparing to provide access to the final documents belonging to the lawyer, diplomat, and historian, Joaquim Nabuco (1849–1910). Composed of diaries, correspondence, photographs, and documents of a diverse nature, researching the collections should reveal unknown aspects of their owners’ intellectual paths, as well as details about their creative or decision-making processes. Some experts go further and are betting these collections will provide new interpretations of cultural movements and historical and political events.

In the case of the 5,600 documents newly donated by Nabuco’s estate, Albertina Lacerda Malta, coordinator of the Rodrigo Melo Franco de Andrade Center for Documentation and Studies on Brazilian History (CEHIBRA), says that most involve his private life. There are postcards sent to his five children, personal photographs, and posthumous tributes. CEHIBRA was launched 45 years ago, when the greater part of the Nabuco archive was donated by one of his children. “Since 2010, we have been negotiating to receive the final fraction of this material. While before we had items related to Nabuco the intellectual, now the collection will offer a vision of the complete man,” says Malta, noting that, in total, the foundation houses 14,600 items from the Pernambuco historian’s collection.

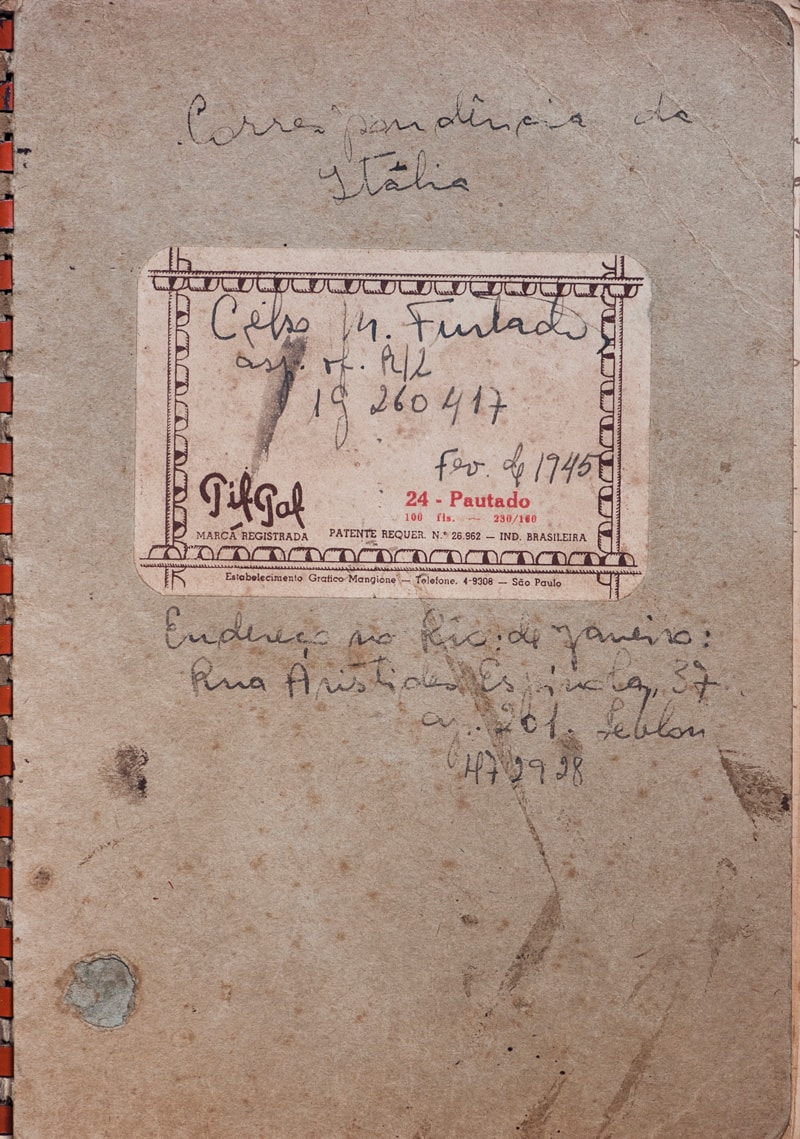

Léo Ramos Chaves / Rosa Freire D’aguiar Archive

Furtado’s estate includes his diaries written during World War IILéo Ramos Chaves / Rosa Freire D’aguiar ArchiveHighlights of the collection include Nabuco’s 21 diaries, some of which were published in a book in 2005 by historian and diplomat Evaldo Cabral de Mello. In the diaries, Nabuco ranges from his impressions of the signing of the Lei Áurea (Brazil’s law to abolish slavery) in 1888, to a record of his trips to his mother’s house to borrow a silver cutlery set. “There are also entries written during the last moments of his life, which let us know that he wrote until only a few days before his death,” says Malta. In addition to the volumes of unpublished information, the arrival of new documents completes the collection available at FUNDAJ. “Until we received this last lot, we only had images of his wife, Evelina Torres Soares Ribeiro [1865–1948], when she was young and newly married. Now we can see photos of her when elderly, living in her house in Petrópolis,” Malta adds.

Social scientist Marco Aurélio Nogueira, from the Institute of Public Policy and International Relations at São Paulo State University (IPPRI-UNESP) is author of one of the first academic investigations dedicated to Nabuco, in his thesis defended in 1983. He states that the new body of documents may breathe new life into research on the diplomat. “Many studies have had apologetic concerns. A line of research that critically explores his intellectual path hasn’t yet been established, although many studies have been put forward,” he adds. For him, Nabuco is a favorite subject for studies on Brazilian liberalism, and this final portion of the estate will make deeper research on this side of him possible. “In Brazil, liberalism has always defended economic freedom, but wasn’t adequately translated into the political and social sphere,” he comments, noting that during the nineteenth century there were few liberals who questioned slavery. Unlike them, Nabuco was concerned with social issues, and was a proponent of Abolition. “Thus, he was at odds with his contemporaries, leaving his mark on the history of ideas in Brazil.”

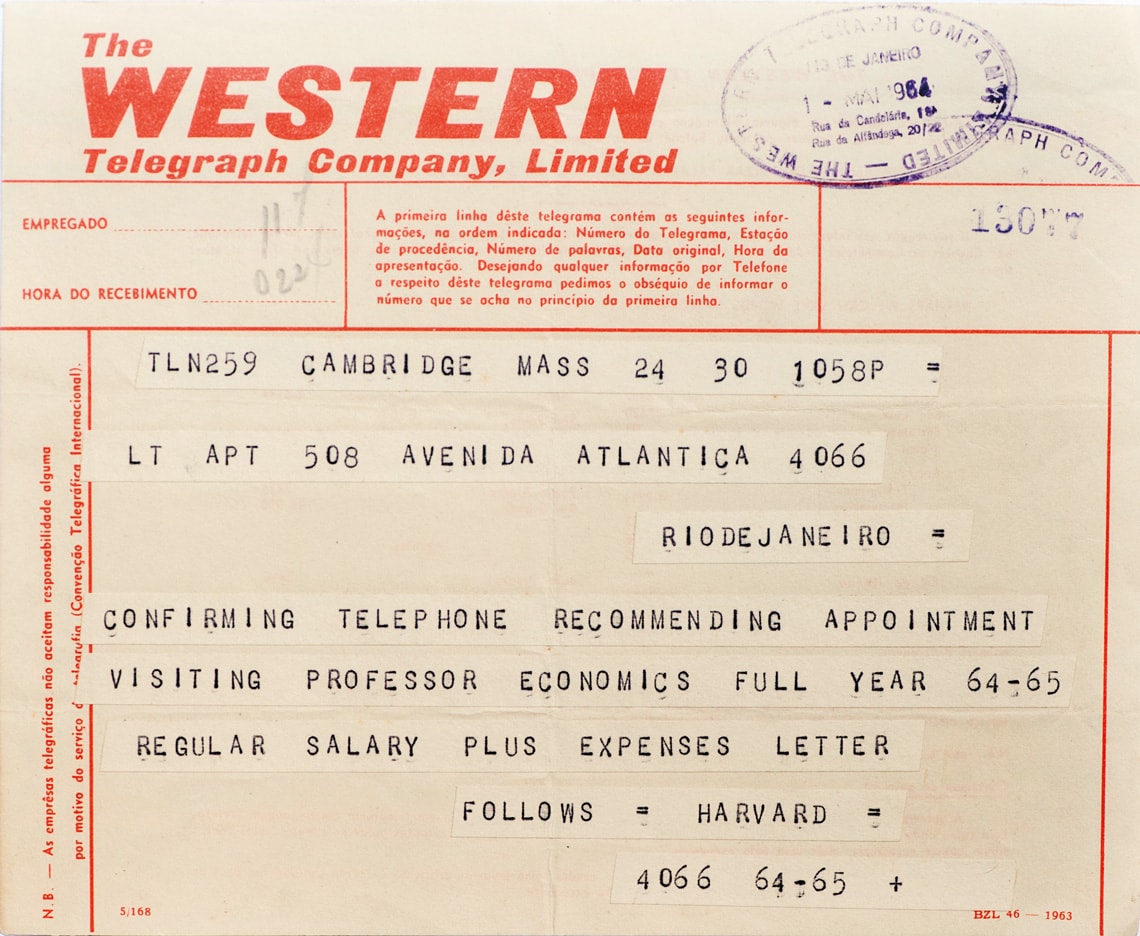

Léo Ramos Chaves / Rosa Freire D’aguiar Archive

A telegram inviting him to Harvard after the military coupLéo Ramos Chaves / Rosa Freire D’aguiar ArchiveNabuco’s change of political position after the Proclamation of the Republic in 1889 is another aspect that, in Nogueira’s assessment, may become better understood through studies of the new documents. While before the event he had advocated “a fiery social liberalism,” after the proclamation he changed his position. At the age of 40, he retired from public life to marry Evelina, and raised a family. “It’s as if there had been two Nabucos, one a social reformer and the other a conservative,” he says. Some apparently contradictory aspects of Nabuco’s diplomatic career may also be illuminated. Despite expressing his admiration for Europe, which he claimed represented “the future of the world,” and holding little appreciation for the United States, Nabuco later became ambassador to Washington. “In the beginning, he showed contempt for Americans, a position that changed over the years, such that he ended his life as a great defender of relations with the United States,” Nogueira observes.

Sociologist Angela Alonso, from the Department of Sociology at the University of São Paulo, explains that FUNDAJ was created in 1949, on the centenary of Nabuco’s birth. Sociologist and anthropologist Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987), then a federal representative, drafted legislation on the occasion to create an institution to house the diplomat’s collection. During the same period, historian and politician Luís Viana Filho (1908–1990) published A vida de Joaquim Nabuco (The life of Joaquim Nabuco; Companhia Nacional, 1952), marking the beginning of a renewal of interest in the diplomat’s intellectual career. “However, the family ended up with part of the estate and it wasn’t known for certain what was in the documents that hadn’t yet been donated,” he says.

Alonso, who wrote Perfis brasileiros – Joaquim Nabuco (Brazilian profiles; Companhia das Letras, 2007) examined all of the diplomat’s correspondence available at FUNDAJ, among other documents. She relates that she encountered gaps in reconstructing Nabuco’s biography, mainly associated with his personal and family life. “We don’t know, for example, how and why he made financial investments in Argentina with his wife’s dowry, money he ended up losing due to fluctuations in the country’s stock market,” she says. Alonso adds that in addition to information about Nabuco himself, the new documents from the estate may also be useful for researchers who want to know what the private life of a member of the Brazilian elite was like, for example, to compare it with the daily lives of families in France, England, and the United States, where the diplomat also lived.

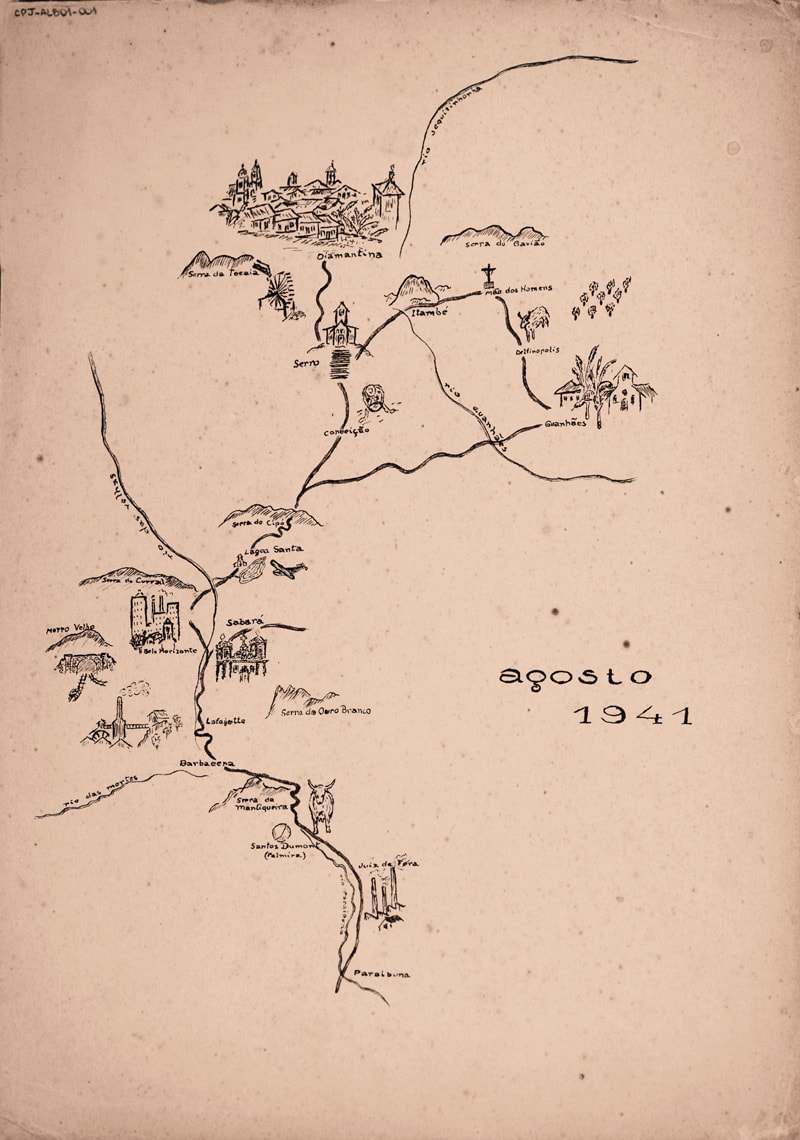

Léo Ramos Chaves | IEB / USP Archive, Caio Prado Jr. Fund

The IEB holds the estate of geographer and historian Caio Prado Jr.: above, a map drawn during a visit to Minas GeraisLéo Ramos Chaves | IEB / USP Archive, Caio Prado Jr. FundThe economist’s choices

Unlike Nabuco’s personal archive, which has been partially available for some time, Celso Furtado’s collection has been inaccessible until recently. It will arrive at IEB in the coming months, 15 years after his death, and is scheduled to be open for research in 2020. Editor and translator Rosa Freire d’Aguiar, Furtado’s widow, says that the estate includes documents kept since the 1940s, including items related to his college years at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Law School (UFRJ), his activities in the Brazilian Expeditionary Force (FEB) during World War II, and his doctorate in economics at the University of Paris-Sorbonne, where he defended the thesis “Colonial Economics in Brazil in the 16th and 17th Centuries.” It also involves material from the 1950s, when he lived in Chile and was part of the United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and from his work at the Superintendency for Northeast Development (SUDENE). Also included are items from when he headed the Ministry of Planning from 1959 to 1964, his years of exile in the United States and Europe after the military coup, and his return to Brazil, when Furtado was Minister of Culture. “The documents from his SUDENE phase, including letters, diaries, and reports, are unpublished,” says d’Aguiar, noting that the economist’s personal library has been at the Celso Furtado International Center for Development Policy (CICEF) since 2005. Until 2016, CICEF was housed in a space at the headquarters of the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), in Rio de Janeiro. Today it occupies a room in the Engineering Club building, also in Rio.

According to d’Aguiar, in October Diários intermitentes de Celso Furtado (The intermittent diaries of Celso Furtado) will be published, with writings the economist penned between 1937 and 2002. “These texts were extracted from 50 notebooks that make up his estate and contain entries written beginning when he was 17, with reflections on which profession to choose, Brazil and the economy, as well as entries written a few years before his death,” she explains.

Léo Ramos Chaves | IEB / USP Archive, Joao Guimarães Rosa Fund

The USP institute received objects from the period when Guimarães Rosa was consulLéo Ramos Chaves | IEB / USP Archive, Joao Guimarães Rosa FundThe texts written in his youth, says d’Aguiar, reveal that Furtado had even thought of pursuing a literary career—there are outlines for three novels in the Diários—and that the decision to interrupt his legal career came after his experiences during World War II. “At that time, he wrote that he wanted to understand ‘the world of men’ and decided to pursue a doctorate in economics,” she says. For the translator, who lived with Furtado for 26 years, another significant moment from the diaries centers around his exile in New Haven, in the United States, when the economist looks back to try to understand what happened to Brazil, and to his own life. Another book is scheduled to be released in 2020 as part of the commemorations of the centennial of his birth, which contains a selection of half a century of Furtado’s correspondence.

Alexandre de Freitas Barbosa, an IEB professor of economic history and Brazilian economics, explains that several lines of research have been developed on Furtado’s thinking. He was a complex author who reinvented himself many times. “Until now, Furtado’s intellectual journey has been analyzed based on his published works,” he says. “The arrival of his personal collection at IEB will allow researchers to understand the subtext of this journey.” Barbosa recalls that the economist wrote three autobiographical works, with accounts of his public and professional life. “The diaries can reveal how key concepts of Furtado’s thinking were developed and why they changed over time,” he observes, not concealing his anticipation regarding Furtado’s thought process during his exile, imposed by the military dictatorship from 1964 to 1979. “Exiles played a key role in shaping the thinking around underdevelopment, development, and dependency in Brazil and Latin America. The letters exchanged by Furtado with other intellectuals will probably enable us to see the differences and commonalities that existed between them.”

The researcher points out that, apart from Furtado’s collection, the IEB houses the archives of geographers and historians Caio Prado Junior (1907–1990), Milton Santos (1926–2001), and Manuel Correia de Andrade (1922–2007), and has just recently received the collection of economist Paul Singer (1932–2018). “These intellectuals tried to understand how social and economic history advanced so unequally across the Brazilian territory. The fact that their collections are now gathered in the same institution should stimulate productive research that connects their thinking,” he says.

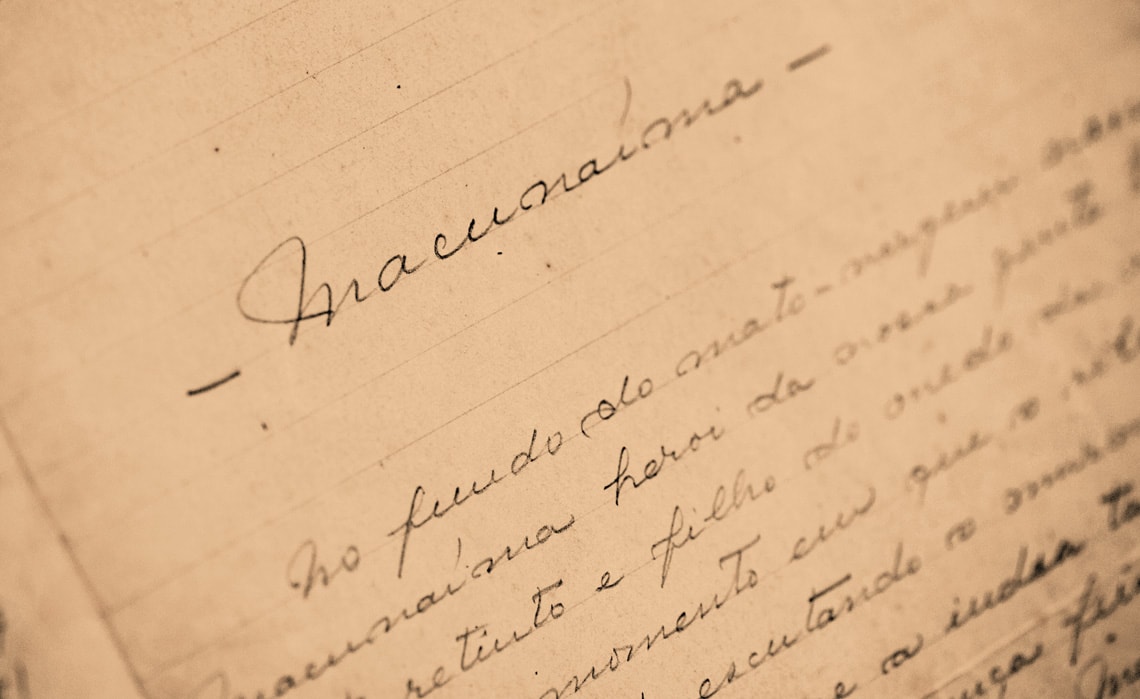

Léo Ramos Chaves | IEB / USP Archive, mário De Andrade Fund

A manuscript of Macunaíma, by Mário de AndradeLéo Ramos Chaves | IEB / USP Archive, mário De Andrade FundHuman aspects

In order for a collection to be accepted by the IEB, donor interest is not enough. Diana Gonçalves Vidal, the institute’s director and a professor at the USP School of Education, explains that each potential donation is evaluated by a committee of professors, researchers, and specialists. Before accepting offers, the institute analyzes the academic and scientific importance of the collection in question and verifies its own ability to ensure the proper restoration and storage of the items. “Institutions like the IEB aren’t warehouses, and they need to ensure their materials are accessible to the public. Moreover, although we receive most of it through donations, that is, without an initial investment, we must consider that accepting new material entails permanent maintenance costs, since donations are irreversible,” she says.

The IEB has a collection of personal trusts from Brazilian artists and intellectuals, including a 250,000-volume library, a collection of 8,000 pieces of visual art, and about 500,000 archival documents including items ranging from the fifteenth century to the present day, and objects that belonged to authors such as Mário de Andrade (1893–1945), Graciliano Ramos (1892–1953), and João Guimarães Rosa (1908–1967). All incoming items are cataloged and described, and each document is treated as a collection piece. For Elisabete Marin Ribas, who works at the IEB Archive, beyond providing revelations about the creation of Brazil and its key political periods, personal collections are important because they make it possible to understand the “human aspects” of the intellectuals that changed the country’s history.

The collection of psychologist Ecléa Bosi (1936–2017), of the USP Institute of Psychology, revealed a few surprises when her family went to organize it. A few months after her death the family discovered a folder containing notebooks and loose papers that contained more than 40 poems. Never previously published, the handwritten verses were digitized and edited for the book A casa & outros poemas (The house & other poems), published in 2018 by Com-Arte, the publishing lab of USP’s School of Communications and Arts (ECA). Written throughout her life, the poems refer to events such as World War II (1939–1945) and the Vietnam War (1955–1975), and mention poets she admired.

“Although she published some translations of poetry, including a book by Galician poet Rosalía de Castro [1837–1885], this facet of my mother was unknown to the family,” says Viviana Bosi, from USP’s Department of Literary Theory and Comparative Literature. According to her, Ecléa Bosi wasn’t a book collector, and kept in her collection only literary works she valued, some autographed or rare, as well as works on subjects such as ecology, aging, memory, and working life. Part of Bosi’s estate remains in the Institute of Psychology office previously occupied by the researcher, who authored more than ten books, and part is in the house where her widower Alfredo Bosi, from USP’s Department of Classical and Vernacular Letters, currently lives. “Before she died, my mother expressed the wish that her collection should be donated to a new university being formed,” says Viviana Bosi, adding that the family is already in talks with one university institution that has expressed an interest in receiving the books.