The Brazilian Academy of Sciences (ABC), based in Rio de Janeiro, announced a memory center in May, that will organize, preserve, and divulge its history, which officially began in 1916. Schools or institutes from the University of São Paulo (USP), the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and others already have theirs. Many public agencies and companies do too. Motivated by the lack of organization of historical information or by external demand — driven primarily by the Access to Information Law, from 2011 — memory centers are broader than documentation centers, because they are hybrid and accommodate various types of documents and objects. Their establishment is generally full of emotions — not always positive, like when organizers find documents in terrible conditions or do not find what they wanted. But there are also unexpected discoveries, which deepen the institutional history and bring topics into the spotlight that deserve further research.

The FAPESP Memory Center website was launched in May, with 43,000 documentary records, especially reports, videos, and podcasts published since 1995 by the journal Pesquisa FAPESP (until 1999, Notícias FAPESP) and since 2004 by Agência FAPESP. With the aim of recording the oral memory of science from the state of São Paulo, 20 interviews were specially conducted for the center with researchers and directors of FAPESP, and are already available online.

“The idea of creating a Memory Center arose during FAPESP’s 60th anniversary celebrations, in 2022,” commented Marco Antonio Zago, president of the Foundation, to Agência FAPESP. “The intention is to leave a legacy for future generations, recording the efforts of a funding agency and of the research community of the state of São Paulo to promote the development of the state based on science, technology, and innovation.”

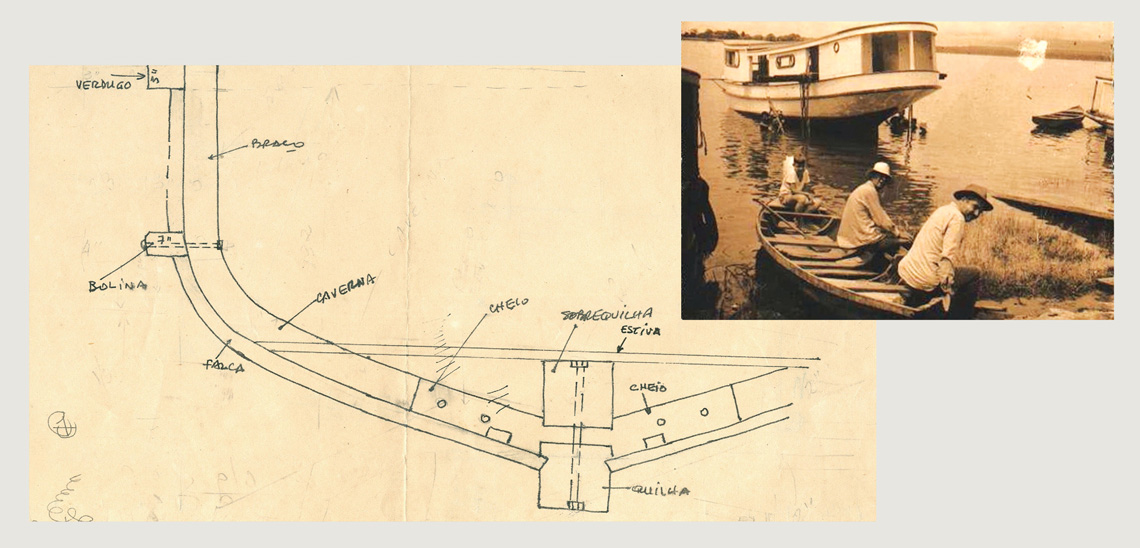

Paraguassú ÉleresRarities of the collection: a drawing of the wooden structure of the boat built in 1967 and used by zoologist Paulo Vanzolini (in the canoe, in the foreground) on trips to the AmazonParaguassú Éleres

Librarian Fabiana Andrade Pereira, coordinator of the center, found — and continually adds to the website — previously scattered documents about the creation, in 1960, and the effective institutionalization, two years later, of the Foundation. The documents already incorporated into the online collection include records in the Official Gazette for the state of São Paulo of the debates in October 1947 in the Legislative Assembly of São Paulo (ALESP), when sociologist and historian Caio Prado Jr. (1907–1990), deputy of the constituent assembly, advocated for the regulation of an article from the State Constitution, promulgated three months earlier, proposing the creation of a foundation to support scientific research in the state of São Paulo.

Articles from the end of the 1940s and beginning of the 1950s from the journal Ciência e Cultura, published by the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC), advocating the realization of the new institution can also be consulted on the website. At the beginning of the 1950s, the newspapers Folha da Manhã — from which Folha de S. Paulo originated — and O Estado de S. Paulo, in turn, published articles that defended or criticized the need for the foundation to fund research in the state. “We can see history being shaped,” observes Pereira.

Another rediscovered document was the report in which jurist and professor at USP Miguel Reale (1910–2006) suggested, in 1962, that the foundation should be “a legal entity of public law, although a private type or model, not subject to the norms of the Civil Code, but to the law and regulations issued by the state.”

ReproductionCover of Nature, from July 13, 2000, featuring the genome sequencing of the bacterium Xylella fastidiosa, carried out by research teams from the state of São PauloReproduction

The work in progress includes the search and inclusion on the website of documents only cited in books about the Foundation, several of them written by the teams of historians Shozo Motoyama (1940–2021) and Amélia Hamburger (1932–2011). Pereira and historian Thiago Montanari, advisor of the center, are seeking historical records about the Foundation in other institutions, such as ALESP itself, the Official Press, universities in the state of São Paulo, and in the Brazilian National Library.

To reach other audiences, besides researchers, the Memory Center has launched an exhibition about the FAPESP Genome Program, started in 1997, with texts, photos, and interviews with then scientific director José Fernando Perez, as well as Andrew Simpson, Fernando Reinach, João Paulo Setúbal, and other researchers leading the work.

For one year, the project of the center included participation from historian Ana Maria de Almeida Camargo (1945–2023), an expert in the organization of institutional archives, and lead author of the book Centros de memória: Uma proposta de definição (Memory centers: a proposed definition; SESC, 2015) (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 333). After the team formulated a document with the guidelines and objectives of the center, Pereira and Montanari went through all of the sectors of the institution, explaining what they intended to do and asking if there were any documents of historic value there.

Without forgetting the present

Upon being invited to be part of the team, historian Silvana Goulart, director of Grifo, a historical project development company, was impressed: used to seeing poorly kept and disorganized documents in public institutions and companies, she found a vast collection of already organized documentation—books, annual reports since 1962, and audiovisual materials. The priority was then to propose ways of making the collection more accessible. “We cannot forget the present,” stresses historian Raphael Novaes, project manager at Grifo. “Anyone needing a document from the collection needs to find it quickly.” Goulart suggests: “We have to carefully assess what we keep,” she says.

Historian Aline Lopes de Lacerda, a member of the executive coordination of the institutional memory policy of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ) agrees: “It’s not necessary to keep everything, but it is not easy choosing what is important. If a study generated several documents, you can keep just the final one, an intermediary one, or a summary of what was done.”

ReproductionOpening page of the virtual exhibition about technical workers at FIOCRUZ and the beginning of the documentary about Sonia and Zilton Andrade, from BahiaReproduction

She recommends collecting information about objects or devices while they are in use. When the pandemic started, the museology team of the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz (COC), one of the entities of FIOCRUZ, already concerned about also recording the present, collected the first containers with the COVID-19 vaccine, and later the vials of the vaccine and the diagnostic kits produced in the BioManguinhos unit. “For the first time, we have created a small collection of contemporary work, which should somehow be preserved,” comments historian Inês Nogueira, of the museology service of the Museum of Life, linked to the COC. “The decision about what to keep should result from an institutional agreement, not from personal or arbitrary actions, to preserve the memory of the people who worked during a historical moment.”

In 2020, FIOCRUZ published an institutional memory policy with guidelines for the teams from its 22 units to identify, organize, and manage documents of historical or scientific value. The following year, it published a call for historical projects. One of the proposals selected, led by social worker Renata Reis Cornelio Batistella, covered the biography of technical workers at FIOCRUZ. In another, sociologist Ulla Macedo Romeu made a film about two researchers from the Gonçalo Moniz Institute, in Bahia, physicians Zilton Andrade (1924–2020) and Sonia Andrade (1928–2022), specialists in schistosomiasis and Chagas disease.

The next stage will be the formation of memory centers in the units of FIOCRUZ, with librarians, journalists, and archivists who can identify documents that will enrich the institutional memory. “A spatula or glass recipients may be important for representing the mode of scientific production at a certain time,” suggests Lacerda. “Documents of objects of historical value often spend decades hidden away.”

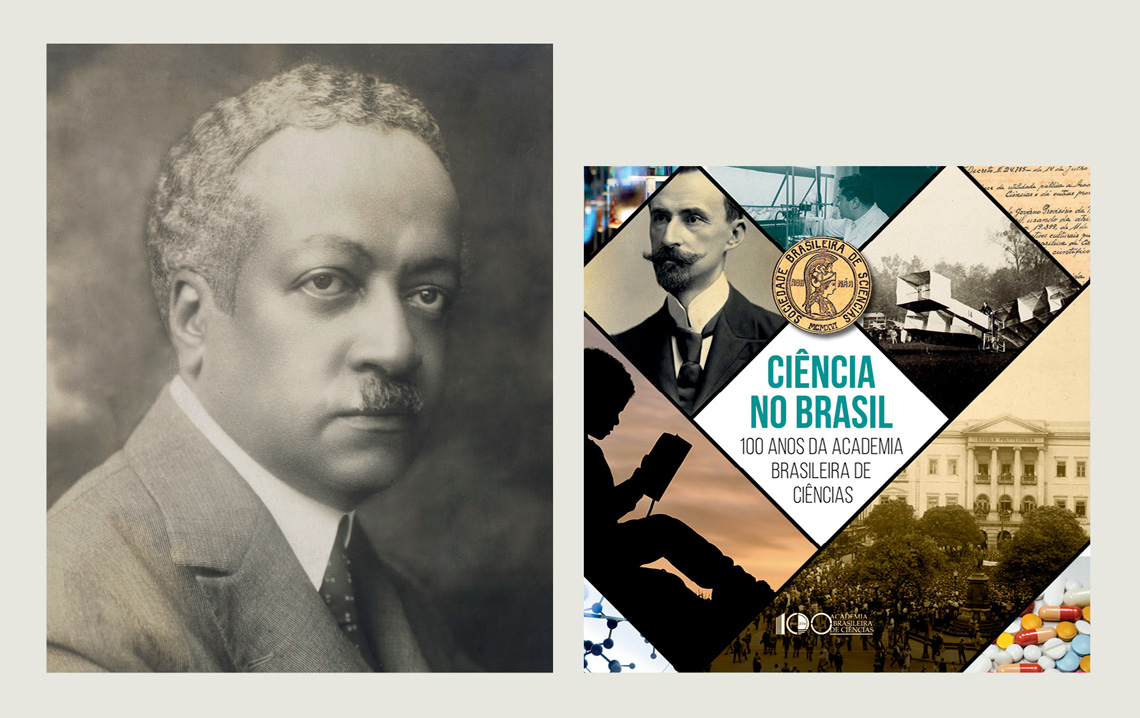

Collection from the National Archives / Wikimedia Commons | ReproductionJuliano Moreira, second president and one of the few Black members of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences, pictured in a book published in 2017Collection from the National Archives / Wikimedia Commons | Reproduction

In January this year, soon after joining the curatorial team for the documents of the ABC Memory Center, historian Paulo Cruz Terra, coordinator of the Oral History and Image Laboratory (LABHOI) of Fluminense Federal University (UFF), entered the room where the boxes of documents containing the history of the institution were kept. “When I saw it, I almost fell over backwards. It was chaos. Almost nothing was cataloged.” In another room, he breathed a sigh of relief upon finding, already organized, the accounting books, meeting minutes, and the personal files of most of the 974 full or affiliate members. Some files contained diaries, academic transcripts, and other documents donated by family members.

In the book Arquivos pessoais: Experiências, reflexões, perspectivas (Personal collections: Experiences, reflections, and perspectives; Association of Archivists of São Paulo, 2017), historian José Francisco Guelfi Campos, of UFMG, and documentalist Lílian Miranda Bezerra, of USP, comment that personal files could be further explored, since they also reflect institutional activities.

Experts from the Laboratory for the Conservation and Restoration of Paper Documents of the Museum of Astronomy and Related Sciences (LAPEL/MAST) will take care of the cleaning, scanning, and storage of the documents from the ABC Memory Center. “We will certainly discover more things than we think,” says Terra excitedly.

One of the research fronts, led by biologist Débora Foguel of UFRJ, has already shown the low participation of women at ABC—just 14% since it was founded. Mathematician and engineer Marília Chaves Peixoto (1921–1961) was the first woman elected to ABC, in 1951, and Helena Nader was the first woman to become president, only in 2022. The number of Black members has not yet been identified, but it is unlikely to reach a dozen, despite the second president having been Juliano Moreira (1873–1933), a Black psychiatrist from Bahia (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 124).

Based on his experience, Terra has taken on the coordination of the Jovanna Baby Trans Memory Center of Brazil, linked to UFF. The aim is to join, organize, and divulge documents about the transgender and transvestite movement in Brazil.

The story above was published with the title “Dusting off the past” in issue 342 of august/2024.

Scientific article

REIS, R. Lembrar, reconhecer, reverenciar: lugares de memória para os trabalhadores técnicos da Fiocruz. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos. Vol. 30, supl.2, e2023071. 2023.

Books

CAMARGO, Ana Maria & GOULART, Silvana. Centros de Memória: Uma proposta de definição. São Paulo: Edições Sesc São Paulo, 2015.

CAMPOS, J. F. G. & BEZERRA, L. M. “Arquivos pessoais e a memória das instituições: O caso da Universidade de São Paulo”. In: CAMPOS, J. F. G. (org.). Arquivos pessoais: experiências, reflexões, perspectivas. 1ª ed. São Paulo: Associação de Arquivistas de São Paulo, 2017. Vol. 1, pp. 62–75.