ÄIORedOil, a microbial oil still under development, intended for the food sectorÄIO

Three years after launching, Estonian biotech startup ÄIO has brought its first product to market: a nutrient-rich oil containing fats, fiber, and protein, made from food industry waste and oleaginous yeasts. Based in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital on the Baltic Sea, ÄIO was cofounded by Brazilian biotechnologist Nemailla Bonturi and Estonian bioengineer Petri-Jaan Lahtvee, both researchers at Tallinn University of Technology (TalTech).

Structurally similar to conventional vegetable oils, the new product is sold in powdered form—an “encapsulated oil” in industry terms—and has already secured European regulatory approval for use as a cosmetic ingredient. A second product, dubbed RedOil because of its color and developed for the food industry, is now in advanced development stages. ÄIO expects to submit its regulatory application in Europe by the end of the year.

Microbial oils—also called single-cell oils (SCOs)—could offer a sustainable alternative to animal fats and plant oils such as palm oil, which is used in nearly half of all packaged foods and in up to 80% of cosmetic and personal care products. If production reaches industrial scale, these oils could serve as feedstock for biodiesel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF)—a technological route the aviation industry is turning to in its push to cut carbon emissions (see Pesquisa FAPESP issues 317 and 337).

ÄIOEncapsulated oil produced by the Estonian startupÄIO

“We’re among the first movers globally in this market,” says Bonturi, who relocated to Estonia in 2016 after earning her PhD. Bonturi was part of the first class in the undergraduate biotechnology program at São Paulo State University (UNESP), Assis campus, and went on to complete her master’s and PhD at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), working under chemical engineering professor Everson Alves Miranda, a pioneer in microbial oil research in Brazil.

“My doctoral work focused on using microbial oils as a biodiesel feedstock,” she recalls. “After defending my thesis, Brazil’s political climate [in 2016] prompted me to look abroad for opportunities,” she says. “I landed a research position at the University of Tartu in Estonia, working with yeasts as microbial factories in a lab led by Petri [Lahtvee]. The job requirements matched my expertise: synthetic biology and bioprocessing.”

The collaboration with Miranda continued, and several PhD students from UNICAMP received grants to participate in her research projects in Estonia. “Petri began focusing on oleaginous yeasts, which soon became the lab’s central research theme,” she says. “As our research progressed, it became clear that microbial oils had greater commercial potential in food and cosmetics.” In 2022, by then already working at TalTech, we founded ÄIO,” Bonturi recalls.

ÄIOFat produced by ÄIOÄIO

Advantages of microbial oils

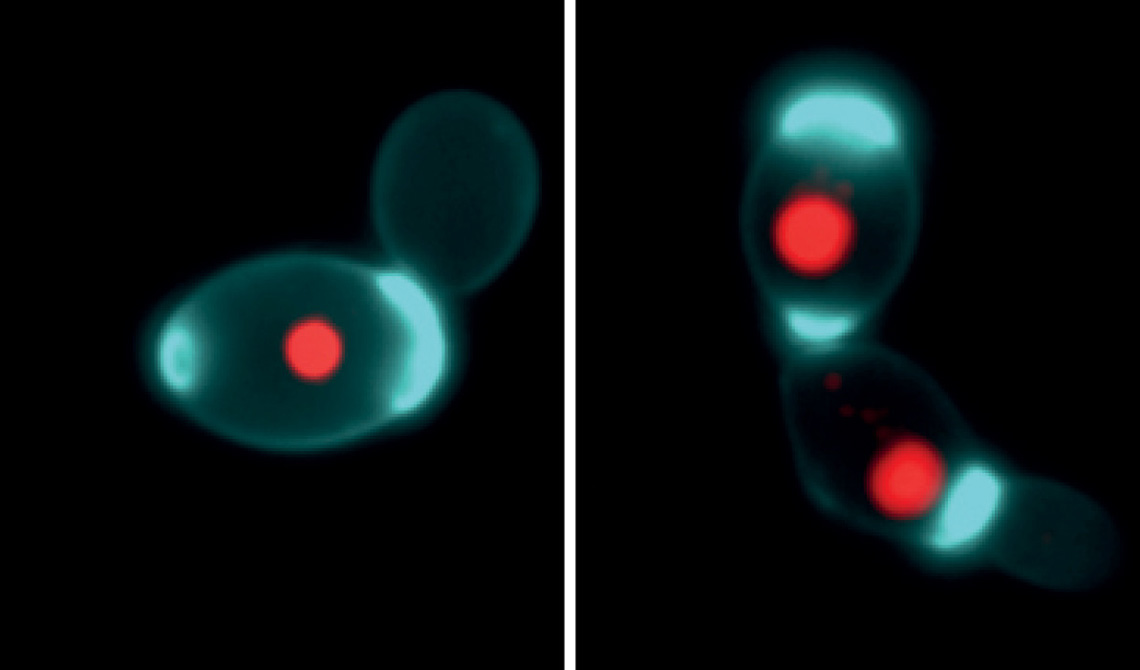

Microbial oils can be produced not only by yeasts—ÄIO uses Rhodotorula toruloides in its formulations—but also by oil-producing bacteria, fungi, and algae. These microorganisms are classified as oleaginous if more than 20% of their dry mass consists of lipids. “Their main components are triacylglycerols—molecules that can be esterified [a chemical reaction between a fatty acid and an alcohol] into biodiesel; and carotenoids, lipid-soluble pigments found in plants and animal-based foods,” explains Miranda, who retired last year but continues to co-advise PhD students in this field.

According to Miranda, microbial oils offer two big advantages over plant-based oils: they don’t compete with food crops for farmland, and they help cut carbon emissions. Global production of vegetable oils and animal fats is estimated to emit over 1 million metric tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) annually. In 2023, total global greenhouse gas emissions reached roughly 53 gigatons of CO2 equivalent—a metric that standardizes the climate impact of various gases like methane and nitrous oxide in terms of CO2. “Our oils and fats require 74% to 97% less land than conventional sources and are made using sustainable methods that considerably lower CO2 emissions,” Bonturi notes.

One major benefit of microbial oils is how fast they can be produced. While making vegetable oils involves planting, growing, harvesting, and processing oilseed crops—a time- and resource-intensive process that can take months or even years and consumes significant amounts of water and land—microbial oils can be made in just a few hours in bioreactors, where microbes grow on a nutrient substrate.

Wesley Cardoso Generoso / Cristiele Saborito da Silva / Bruno Motta Nascimento / CNPEMLipid accumulation in oil-producing yeast visualized using Nile Red fluorescent stainingWesley Cardoso Generoso / Cristiele Saborito da Silva / Bruno Motta Nascimento / CNPEM

“Put simply, instead of converting sugars into alcohol like in brewing or winemaking, the yeast eats the sugar and stores fat,” says Bonturi. “Of course, the underlying metabolic pathways are quite different. Once cultivation is complete, we separate and harvest the yeast. For our powdered oil product—made from dried yeast biomass—we use a drying step. To produce liquid oil, we add an extraction step after harvesting the yeast.”

Microbial cultivation can use a variety of feedstocks, including sugarcane, corn starch, or byproducts from the food, agricultural, and timber sectors. ÄIO uses sawdust—Estonia’s most abundant industrial byproduct—which is rich in xylose, a type of sugar ideal for microbial growth. “Microorganisms don’t need to grow on waste, but this boosts the environmental and economic sustainability of the process,” explains Miranda, who has received FAPESP funding for his research.

Miranda notes that the cultivation phase is key to both process efficiency and economic viability. “The challenge is designing low-cost culture media that provide carbon and energy—usually from sugars—while still ensuring the bioreactor delivers high yields,” he says. In the recovery and purification stage, he adds, it’s important to avoid using toxic solvents.

ÄIO Bonturi in ÄIO’s research lab in Tallinn, EstoniaÄIO

“Harnessing microbes to convert cheap raw materials like food industry waste into high-value products—proteins, oils, or specialty molecules—is a promising strategy to cut dependence on conventional sources like crops or livestock,” says Andreas Karoly Gombert, a chemical engineer and yeast specialist at UNICAMP’s School of Food Engineering. “As long as the molecules are chemically similar, microbial oils could substitute for vegetable oils in cosmetics, processed foods, and personal care products,” he adds.

ÄIO currently runs a 300-liter pilot plant used for testing yeast strains and optimizing its production process. At the moment, commercial-scale production is handled by external manufacturing partners. The company plans to open its own industrial facility within the next two to three years to produce at scale. In parallel, it is also looking to license its proprietary technology to interested manufacturers. Scaling up remains one of the startup’s toughest hurdles.

So far, ÄIO’s 20-person team has secured over €8 million in research grants and an additional €7 million in private capital. In late 2024, ÄIO took home top honors in the Food category at the Baltic Sustainability Awards, which featured over 70 innovative companies from across the Baltic region. Around the same time, Bonturi was honored with UNICAMP’s Distinguished Alumni Award.

“It was a tribute to her remarkable path as a researcher. Nemailla dreamed of being a scientist since she was a child,” says Miranda. “She has a strong ability to learn, collaborate across disciplines, and embrace challenges. She took a leap moving to a new country, and not long after, went from postdoc to lab manager to cofounder of ÄIO alongside Petri,” he adds.

ÄIO Sawdust used as a substrate for growing oleaginous yeastsÄIO

The research team led by Miranda and Bonturi has published roughly 20 papers on microbial oil production. A 2020 study in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology explored how R. toruloides converts xylose into microbial oil under different growth conditions, including exposure to light and the addition of hydrogen peroxide. “Light exposure increased carotenoid output by 70% and lipid production by 40% compared to what were then considered optimal conditions,” says Miranda. “Hydrogen peroxide—better known as common household peroxide—didn’t affect carotenoid levels, but it did result in a high lipid yield.”

A more recent study, published in the Journal of Cleaner Production in 2022, assessed the technical, economic, and environmental feasibility of an integrated sugarcane biorefinery that produces first-generation bioethanol, bioelectricity, and biodiesel—with microbial oil from R. toruloides feeding the biodiesel production line. The authors concluded that the integrated process showed positive economic performance and is a viable model for industrial-scale production.

“Professor Miranda’s group has made a major contribution to microbial engineering, particularly in developing biorefinery technologies,” says biologist Rafael Silva Rocha, founder of genomic big data company ByMyCell and a former professor at the University of São Paulo’s Ribeirão Preto Medical School (FMRP-USP) between 2015 and 2022. “Our group focused on using synthetic biology to turn microbial oils into precursors for high-value compounds,” he adds.

ÄIO Cosmetics made with ÄIO’s microbial oilÄIO

Aviation fuel

At the Brazilian Center for Research in Energy and Materials (CNPEM) in Campinas, scientists are exploring how microbial oils made from sugarcane juice could be used to produce sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). The process includes extracting and chemically processing the juice, followed by converting its sugars into lipids using oleaginous yeasts, according to a January study in Bioresource Technology.

“The hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids [HEFA] pathway is currently the primary method for making SAF,” says chemical engineer Tassia Lopes Junqueira, who heads the project. “But limited access to traditional feedstocks and sustainability challenges limit how far it can scale.” That’s where microbial oils come in, Junqueira says—they offer a promising alternative. “A key barrier is the high cost of producing microbial oil, mainly due to the need for large-scale aerobic bioreactors” she explains.

According to the Bioresource Technology study, the cost of producing SAF from microbial oils is estimated at $1.83 to $3 per liter—up to four times more expensive than fossil-based jet fuel, but within range of other sustainable fuel production methods. “Microbial oils could deliver up to four times more SAF per hectare than soybean oil,” Junqueira notes. Building on these results, the CNPEM team is now working on screening and genetically optimizing oil-producing yeasts found in Brazil’s native biodiversity. “This is a critical step toward scaling microbial oil production and making it cost-competitive,” she says.

The story above was published with the title “Sustainable oils from microbial biofactories” in issue 351 of May/2025.

Projects

1. From cell factory to integrated biodiesel-bioethanol biorefinery: A systemic approach applied to complex problems at micro and macro scales (n° 16/10636-8); Grant Mechanism Bioen Program; Principal Investigator Roberto de Campos Giordano (UFSCar); Investment R$11,449,535.74.

2. Integrated study of single cell oil production using unconventional yeasts from hemicellulosic hydrolysate and its cell recovery by flotation, in pursuit of applications for biorefineries (n° 13/03103-5); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Responsible researcher Everson Alves Miranda (UNICAMP); Investment R$224,737.72.

3. Development of a selective adsorbent for the plasmid DNA purification process for application in gene therapy and DNA vaccine studies (n° 07/58430-0); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Everson Alves Miranda (UNICAMP); Investment R$121,990.62.

Scientific articles

PINHEIRO, M. J. et al. Xylose metabolismo and effect of oxidative stress on lipid and carotenoid production in Rhodotorula toruloides: insights for future biorefinery. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. Vol. 8. Aug. 19, 2020.

LONGATI A. A. et al. Microbial oil and biodiesel production in an integrated sugarcane biorefinery: Techno-economic and life cycle assessment. Journal of Cleaner Production. Vol. 379. Dec. 15, 2022.

MARCHEZAN, A. N. et al. Alternative feedstocks for sustainable aviation fuels: Assessment of sugarcane-derived microbial oil. Bioresource Technology. Vol. 416. Jan. 2025.