Photography

A retrospective on Marc Ferrez brings to light his dialogue with science and expands knowledge of his work

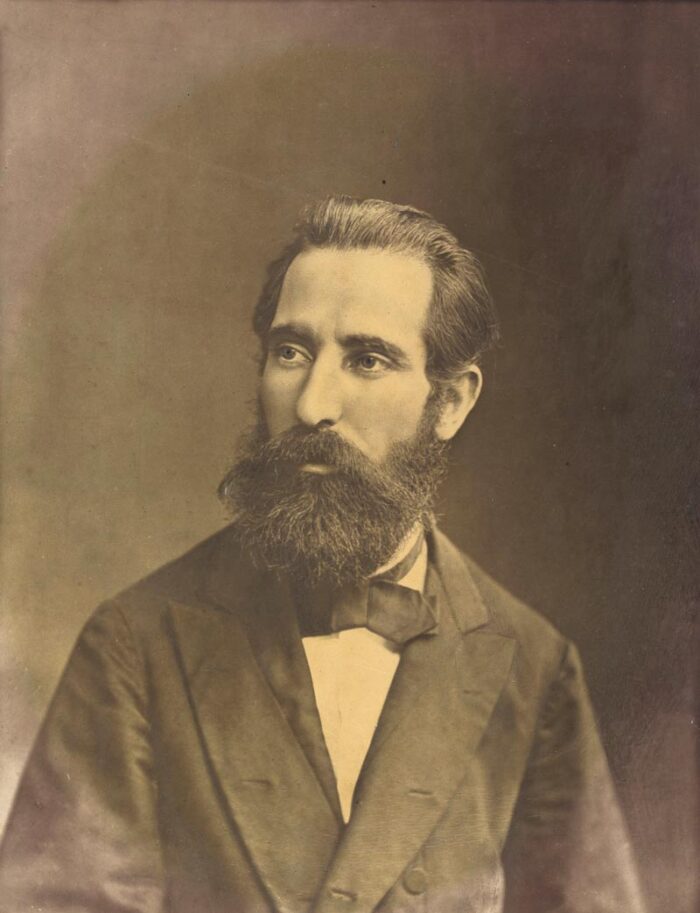

Considered one of the leading Brazilian photographers of the nineteenth century, Marc Ferrez (1843–1923) gained fame primarily for recording the landscape of his birth city, Rio de Janeiro. Since his collection was acquired by the Moreira Salles Institute (IMS) a little over two decades ago, some little-known aspects of his work have been revealed. For example, the exhibition now on display at the institution in São Paulo broadens our knowledge of his cartography production. An intrepid traveler, it’s now known that half of his photographic work was actually unrelated to the city of Rio. His multiple interests, which included scientific knowledge, also emerge at the show. Bringing together over 300 items, including both documents and images, as well as work by other photographers, the exhibition is open to the public until August 25.

“Ferrez was the photographer who most traveled Brazil during the nineteenth century. Not only physically, but also in his photography,” says Sergio Burgi, IMS photography coordinator and curator of the retrospective, titled Marc Ferrez: Territory and Image. “One of our goals was to take an accurate look at the work he did outside of Rio.” It was a major challenge, considering the size of the collection to be researched, about 9,000 images, which included a set of 4,000 large-format glass negatives. In total, Ferrez’s collection, organized by the photographer himself starting in 1873, then maintained by his family until the institute acquired it in 1998, comes to some 15,000 items. “We wanted to try to think of his camera and its relationship to the documentation of the Brazilian territory,” explains Burgi. “In the field of social documentary, for example, Ferrez was the first to record the Botocudo people of southern Bahia, and in the period before Abolition, he produced important photographic documentation of individuals enslaved on coffee farms in the Paraiba Valley, exposing the system’s brutality.”

“It took two years of research to prepare the book. It was almost like detective work,” notes historian Ileana Pradilla Ceron, head of the institute’s photography research center and editor of Marc Ferrez: Uma cronologia da vida e obra [Marc Ferrez: A chronology of life and work]. “What emerges, especially from his work on the large commissions and construction projects, is a portrait of a man of special sensitivity with a keen eye.” Ceron explains that Ferrez was not simply a professional who photographed large engineering projects for hire. “He was able to realize, visually, a conception of Brazil held in the minds of the engineers, at a time when all men of science were engineers, and engaged in the modernization of the nineteenth and early twentieth century.” In Ceron’s view, Ferrez was neither a studio photographer nor particularly authorial. “He was a man of scientific reason. His photos are organized with a rational eye.”

During the research she found, for example, that many of his photographs were commissioned by railroad companies and international fairs that were selling the “modern Brazil.” “They weren’t simply work invitations to Ferrez, they were business partnerships,” she adds. In 1875, the photographer was part of the Geological Commission of the Empire, headed by Canadian-American geologist Charles Frederick Hartt (1840–1878). Ferrez, who would become known as the commission’s official photographer, did not participate in all the trips. But thanks to the abundant documentation about his life, it is still possible to reconstruct the work he did then, which took place over a period of about three years. Stored in the Historical Archive of the National Museum, the commission’s own collection was destroyed by the fire that devastated the museum in 2018. In addition to the photos from Ferrez’s collection, the IMS retrospective includes two original albums—never before shown in Brazil—that belong to the Getty Museum collection in Los Angeles, United States, and which capture the Geological Commission’s first expedition.

In the exhibition, the relationship between science and photography also shows up in Ferrez’s ongoing dialog with astronomers at the National Observatory, and in the failed attempt to record a total eclipse of the sun in Passa Quatro, Minas Gerais in 1912. “Ferrez took an optimistic view of science and technology, and believed in their transformative power. This was partly because, with his camera, he was a privileged witness to this transformation,” observes Christina Helena Barboza. A researcher at the Museum of Astronomy and Related Sciences (MAST) and a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro State (UNIRIO), Barboza highlights the exchange of information and experience in the field of imaging that took place between Ferrez and the astronomer and experimental physicist Henrique Morize (1860–1930). “Particularly in the case of X-ray imaging, I believe Ferrez collaborated with Morize, who brought the new technology to Brazil a few months after its discovery in early 1896.” In Burgi’s view, Ferrez, consistently interested in innovation, brought technique to the then incipient scientific imaging process. “A pioneer, he created a grand dialogue between photography and science.”

Republish