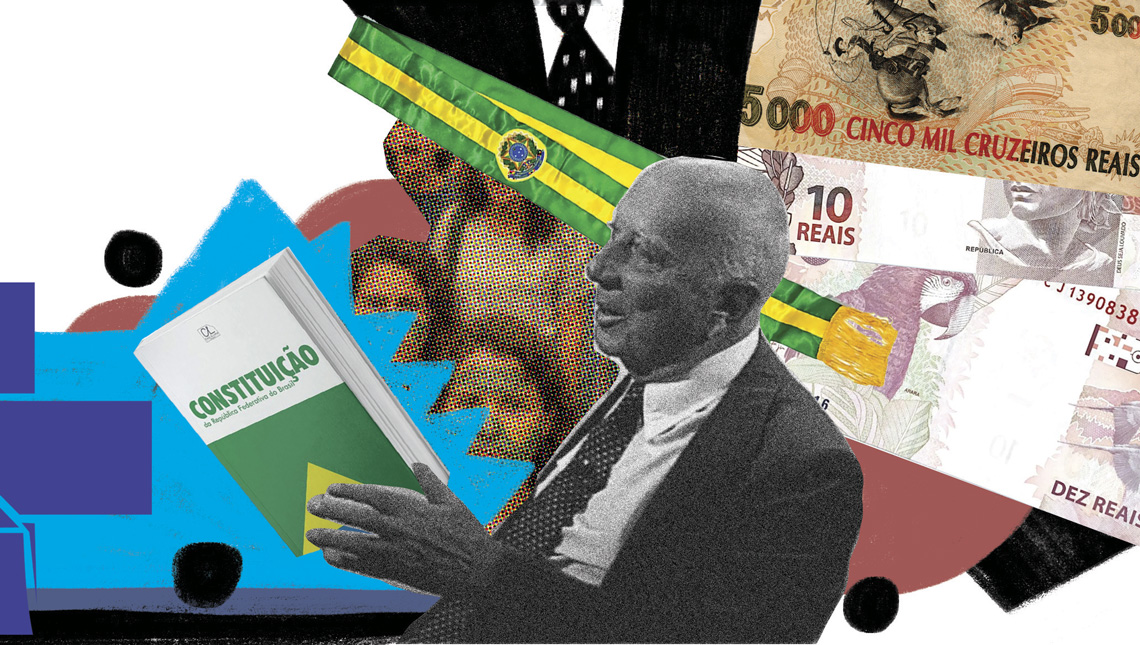

Forty years ago, on April 21, 1985, Tancredo Neves (1910–1985) passed away. If not for a generalized infection, the Minas Gerais politician would have been the first civilian to assume the Presidency of the Republic after 21 years of military dictatorship. Three months previously he had won the indirect presidential election at the National Congress, in a joint ticket with former supporter of the military regime and Maranhão State politician José Sarney, who ended up assuming the presidency. The tortuous redemocratization process maintained figures who had kept the dictatorship in power. A conciliator and conservative, Neves calmed the inquietude of the military rulers who, on leaving the Planalto Palace, were fearful of the opposition ascending to power. During his presidential campaign, the expression “New Republic” was coined to define a democratic system marked by conciliation, in which a settling of scores with all the dictatorial abuses was out of the question.

“In an original play on words, used to signal that he would not go after the armed forces, [Neves] presented his candidacy as ‘changist’ rather than ‘oppositionist.’” This emblematic phase of Brazilian redemocratization, with its departures from and continuations of the authoritarian past, is described in the book Democracia negociada: Política partidária no Brasil da Nova República (Democracy negotiated: Party politics in New Republic Brazil) (FGV Editora, 2024). In this work, historian Leonardo Weller, a professor of the São Paulo School of Economics at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV-EESP), and political scientist Fernando Limongi, a faculty member at the same institution and also at the University of São Paulo (USP), provide a potted Brazilian political history over the last four decades. Among other aspects, they demonstrate that Brazilian democracy in this period was characterized by conflict resolution through consensual arrangements among the political elite, which guaranteed two decades of economic and political stability between 1994 and 2013. They also explain how a system based on negotiations with representatives of conflicting interests was able to produce unprecedented and significant social change in the country’s history.

According to Limongi, the success of democracies in promoting negotiated solutions can lead to insatisfaction when seeming like agreements made between elites seeking to protect their interests. “When we look at the data, however, we see that democracy moves, produces movement, albeit slower than we would like,” says the researcher. “Brazil has seen little growth since the 1980s, but the social indicators have improved considerably and a welfare state, though not perfect, has taken root,” adds Weller. According to the World Bank, extreme poverty afflicted 25% of the Brazilian population in 1985. In 2022, some 37 years after redemocratization, this figure stood at 3.5%.

To explain redemocratization, Weller and Limongi revert to the government of General Ernesto Geisel (1907–1996), which began in 1974. After a period of violent repression from 1968, with random arrests, torture, and the assassination of opponents, the president and his nucleus of power opted for a political reopening. The researchers point out that Geisel was complicit in the hardline brutality but saw the need to act and retain control of the barracks. In the words of the authors, the reopening was, “slow, gradual, and faltering,” a play on Geisel’s statement that the opening would be “slow, gradual, and safe.” Despite popular pressure, the amendment proposing direct elections for president was defeated in Parliament in 1984, and the Tancredo-Sarney ticket was elected the following year.

Veridiana Scarpelli

Veridiana Scarpelli

In 1987, with Sarney the incumbent President, the Constituent National Assembly was installed. According to political scientist Antônio Sergio Rocha, of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Guarulhos campus, the progressive wing of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB) dominated the early stages of the process, but the conservative majority mobilized in resistance. The most symbolic example of this impasse is in Congress members’ inability even to agree on the content of the constitutional text’s preamble. This was resolved through negotiation between party leaders, who brokered one-off agreements, reconciling worldviews and conflicting interests. “For twenty months there was a pitched battle in Congress, with nine drafts of the Constitution before the final text,” says Rocha, currently finalizing four volumes of the project “Memória da Constituinte” (Memory of the Constitutional), which he coordinates at the Center for Contemporaneous Culture Studies (CEDEC). Planned for release in 2025, the books provide, among other information, a detailed timeline of happenings in the assembly between 1987 and 1988.

The result was a Charter which, while not promoting reforms of ownership structures, formed the basis for a social welfare state. For example, the text provided for a level of healthcare assistance to the poorest but retained a hybrid system by which the wealthiest would still be able to pay for quality treatment. Nevertheless, the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) was one outcome of the document. Historian Fernando Perlatto, of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF), believes that although full of contradictions, the Constitution made significant advances in consolidating civil and social rights, such as the exercise of popular sovereignty not just by the representative system, but also through plebiscites and referenda. “The pressure of social movements helped the Constitution to consolidate democratic elements,” he points out.

The civilians inherited considerable external debt and rampant inflation from the dictatorship. Tancredo’s nephew Francisco Dornelles (1935–2023) was the New Republic’s first Minister of the Treasury to attempt to tame inflation. With no political backing, Dornelles lasted just five months in post before being replaced by businessman Dilson Funaro (1933–1989), who proposed an adjustment in government accounts, renegotiation of the external debt and, above all, the freezing of prices, salaries, and interest rates. His Cruzado Plan initially controlled inflation, but in less than one year could not resist price increases and culminated in an external debt moratorium. Economist Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira replaced Funaro in 1987; The Bresser Plan focused on a renewed adjustment of the public accounts and price freezes but also went under in a short space of time. Maílson da Nóbrega, Sarney’s last Treasury Minister, proposed a package of privatizations and fiscal adjustments which proved ineffective, with price increases attaining hyperinflation status—more than 50% per month—at the end of 1989.

These personalities are analyzed in the book Os homens da moeda: O que pensavam os ministros da Fazenda da Nova República (1985-2018) (The currency men: What the New Republic Treasury Ministers were thinking), arranged by economist Ivan Salomão, of the USP School of Economics, Business and Accounting (FEA-USP), and released last year by Editora Unesp. Penned by Salomão in collaboration with other researchers, each of the 15 chapters is dedicated to the thinking, intellectual output, and political activity of those in command of Brazil’s economic policy during the New Republic, from Dornelles to Henrique Meirelles (who held the post between 2016 and 2018). Despite the male-centric title, the book also examines the actions of Zélia Cardoso de Mello, the first—and to date the only—woman to occupy the position.

The civilians inherited considerable external debt and rampant inflation from the dictatorship

The book tells how, in the early days of the Fernando Collor de Mello Administration in 1990, Cardoso de Mello attempted to control inflation by reducing liquidity—the amount of currency in circulation—with a drastic measure: the sequestration of financial assets, including savings portfolios. The plan soon became unpopular and was ineffective against inflation. This economic instability precipitated a political crisis, culminating in 1992 with the impeachment of Collor, a conservative outsider who, to the surprise of many, had beaten progressive candidates in the first direct elections for president since 1960.

“The currency men” demonstrates that inflation would only come to be controlled by the Real Plan from 1994, during the mandate of Itamar Franco (1930–2011), marking the start of two decades of political and economical stability. This period also saw coalition presidentialism consolidated—generally speaking, under this system the Executive Branch uses government positions to lobby for support in the Legislature and impose its political agenda.

Economic stability enabled elementary education to be universalized, and revenue transfer programs implemented, such as the Bolsa Escola (School Allowance), during the two terms of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (PSDB), 1995–2002. The first two terms of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), between 2003 and 2010, also followed the playbook for containing public spending, but focused on a real-terms increase in the minimum salary, with expansion of revenue transfer programs such as the Bolsa Família (Family Allowance), which led to considerable social transformations in the country. In Salomão’s opinion, this demonstrates that it is possible to implement changes in Brazil, even with a very tiny allocation from the federal budget. “The increase in the minimum salary was paramount for bringing low-income families into the consumer market and thereby driving economic growth, which attained 7.5% per annum in 2010,” recalls the economist.

The social changes arising from the New Republic took place amidst lower average economic growth than that registered between 1930 and 1980. According to Salomão, a convergence of favorable factors in the preceding period—fast moving urbanization with abundant available labor, facilitating investments in industrial production—was not repeated from the 1980s. One of the central theses of Weller and Limongi’s book is that in two decades of stability, Brazilian democracy, despite moving slowly, provided a number of unprecedented social advances in the country’s history: health and education systems were universalized, and dozens of millions emerged from hunger and extreme poverty.

Veridiana Scarpelli

Veridiana Scarpelli

Between 2013 and 2016, the political and economic crisis culminated in the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff (Workers’ Party – PT) and in the ascension of military dictatorship apologists in politics. Amid all this institutional strain, the end of the New Republic has been pegged by analysts drawing attention to the depletion of the political system in the last 40 years. “From 2013, political groups that proposed resuming elements of the military dictatorship directed their attacks primarily against the democratic pillars of the 1988 Federal Constitution,” says Perlatto, who collaborated on arrangement of the book A Nova República em crise (The New Republic in crisis) (Appris, 2020).

Salomão says that the political system of Jair Bolsonaro (2018–2022), which gave the Legislative Branch wide-ranging control over the federal budget, drastically reduced the Executive’s bargaining power and initiated what the Economist refers to as “de facto semipresidentialism,” one of the reasons for which he considers the New Republic to have ended. “Government capacity to formulate and apply economic policy has been narrowed,” he says.

For Limongi, sounding the death knell for the New Republic is going too far. “The Constitution is still valid, and the electoral calendar is open, says the researcher. Weller agrees that the system is undergoing changes, “but we are not necessarily living in another regime,” adding that “if the attempted coup of 2023 had been successful, things would be different.” For his part, Perlatto considers that the clash between progressive and reactionary sectors should still be seen as a political dispute within the New Republic, but issues an alert on elements of continuity of the authoritarian past. “The role of the military in the political order and the militarization of the public security apparatus should not be normalized,” warns the historian.

The story above was published with the title “The New Republic at 40” in issue 351 of May/2025.

Books

LIMONGI, F. & WELLER, L. Democracia negociada: Política partidária no Brasil da Nova República. Rio de Janeiro: FGV Editora, 2024.

PERLATTO, F. et al. (Eds.). A Nova República em crise. Curitiba: Appris, 2020.

SALOMÃO, I. C. (Ed.). Os homens da moeda: O que pensavam os ministros da Fazenda da Nova República (1985–2018). São Paulo: Editora Unesp, 2024.