The Butantan Institute last December 12 signed a collaboration agreement using an innovative model that promises to speed up development of its US-patented dengue vaccine, now in final, Phase 3 trials on volunteers in Brazil. In a country more accustomed to buying foreign scientific technology and services, the new agreement with US pharmaceutical company MSD (Merck Sharp & Dohme) will be a game changer, bringing in foreign investment while providing a platform to share data and experience so the products developed by the two partners—one public and one private—can get to people faster.

Under the agreement, Butantan will receive a US$26 million upfront payment from MSD—whose own dengue vaccine candidate is in an earlier stage of development—in exchange for access to the São Paulo institute’s dengue vaccine trials and development process. MSD has also agreed to pay an additional US$75 million over the next 24 months. Butantan could also receive royalties if the company meets vaccine marketing targets outside Brazil. To date, the Butantan vaccine program has received R$ 224 million in investment from the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), FAPESP, the Butantan Foundation, and the Brazilian Ministry of Health.

• Life-saving vaccines

As a rule, Butantan and MSD will not compete with each other in any market. The Brazilian institute has exclusive rights to produce the vaccine in Brazil, and MSD in the US, Japan, China, and Europe. “Butantan has achieved world-class excellence in developing vaccines for which there is global demand. This is the first technology transfer of this kind between a Brazilian institute and a global pharmaceutical company,” says physician Dimas Tadeu Covas, a director at Butantan. “We’re thrilled to see a program building on 10 years of FAPESP-funded research develop into a product that could reach global markets within the next few years,” says Marco Antonio Zago, the current FAPESP president and previously São Paulo State Secretary for Health.

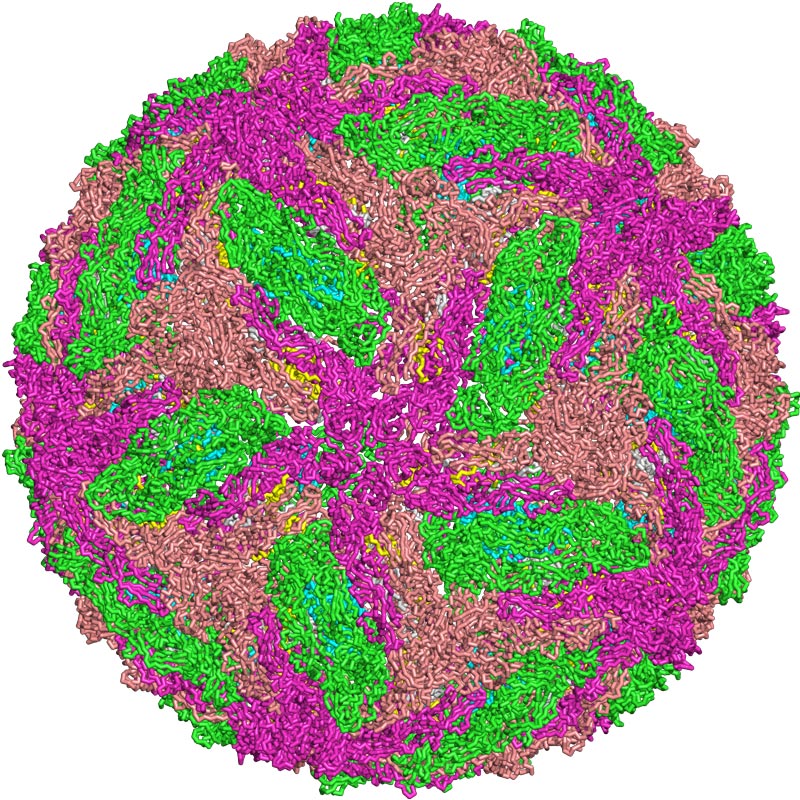

PDBE

A representation of the dengue virus, which has four serotypesPDBEThe partnership was made possible by the fact that Butantan and MSD both based their vaccines on a set of genetically modified dengue virus strains developed by a team led by Stephen Whitehead of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), a US National Institute of Health (NIH). When international collaborations to develop the vaccine were initiated, the NIH established geographical domains for each partner in advance.

The vaccine developed by Butantan, designated as Butantan-DV, is made of live attenuated viruses, as is MSD’s. It has the advantage of being tetravalent, meaning it provides protection against all four dengue virus types. Butantan’s clinical trials have been designed to evaluate product adequacy for a broad age bracket, from 2 to 59 years. The vaccine has so far been shown to be safe, causing only a few adverse reactions that are similar to those caused by other vaccines. No other dengue vaccine developed from NIH-licensed material is at such an advanced stage of clinical trials. In late 2015, Sanofi Pasteur launched Dengvaxia, the only commercially available vaccine against dengue, which was developed with a different technology from the NIH’s. But the French company’s product has several drawbacks: it has a relatively low efficacy rate (60%), it can cause adverse reactions, and it is contraindicated for people who have never had dengue.

The collaboration between Butantan and MSD began to take shape shortly after the Brazilian-developed vaccine passed Phase 2 clinical trials that demonstrated it was safe and effectively stimulated the immune system to produce antibodies against the four dengue-fever viruses. Although the trials have already been completed, the results have yet to be published. “The paper on this study has been recently submitted for publication and we are awaiting a response,” explains Alexander Precioso, director of Butantan’s Clinical Trials Division. “Publishing the Phase 2 trials is not a condition for moving to Phase 3. A clinical trial is approved at the health-surveillance and ethics level.” After being successfully tested for safety and low toxicity in Phase 1, a vaccine (or drug) candidate must undergo Phase 2 testing covering additional safety aspects and a therapeutic study involving a number of participants, as of yet limited, to determine whether the product can be useful for its intended purpose. Phase 3 consists of a trial, usually multicenter, with a large number of volunteers across varying age profiles to determine efficacy and confirm the vaccine or drug’s safety profile.

The dengue vaccine is being tested on 17,000 Brazilian volunteers aged 2 to 59 years

While still pending publication in a scientific study, the results of the Phase 2 trials of the Butantan vaccine, covering 300 volunteers recruited by the University of São Paulo School of Medicine (FM-USP), have been reported to the MSD and other companies and institutions at scientific meetings, conferences, and events. “The Phase 2 studies were extremely promising and caught our attention,” says Guilherme Leser, director of government affairs and access at MSD Brazil. “We promptly initiated discussions with Butantan about the possibility of a collaboration, as Brazil then had the highest prevalence of dengue cases globally. The country was experiencing outbreaks of the disease in the Southeast and Northeast, and the large number of cases allowed Butantan to get a head start on Phase 3 clinical studies—the last stage, to evaluate vaccine efficacy.” In 2015 and 2016, Brazil recorded about 1.5 million cases of the disease. In 2017 and 2018, the number dropped to about 240,000.

The Phase 3 trial of the Butantan vaccine, which has a goal of covering 17,000 people over a five-year follow-up period, is well underway and near completion. The trial divided volunteers into three age brackets: 2 to 7, 8 to 17, and 18 to 59. Only the youngest age group, the hardest to recruit for clinical trials, has yet to reach the target number of participants. The difficulty in recruiting this group of volunteers is explained by both the surprisingly small number of dengue cases in the last two years and the need for parents’ permission for their children to participate in the study. “There is some evidence that the 2019 epidemic will be larger than in 2018,” says Esper Kallás, a professor at FM-USP and coordinator of one of the 16 trial centers. “At year-end 2018, dengue cases in São Paulo already exceeded estimates for the period. Because epidemics only come in full force in February, we’ll likely be seeing a very large number of cases next season.”

The 16 trial centers in Brazil are working to complete the required number of volunteers. “To demonstrate that the vaccine is effective we need to document 100 cases of the disease among volunteers, but we have yet to reach that number,” explains Kallás. One-third of volunteers are in the control group, which is given an innocuous preparation, and two-thirds receive the actual vaccine. When the one hundred patient target is reached, the researchers open the files of participants who became infected and identify which group they were in. If almost all cases received the placebo, this will be a very strong indication that the vaccine is effective. However, the clinical trial will not have been completed if and when this occurs. It will also need to evaluate the protection offered by the vaccine against each serotype of the virus—in Brazil, most cases of dengue are type 2 and 3—across the different profiles of patients who have or have not been infected.

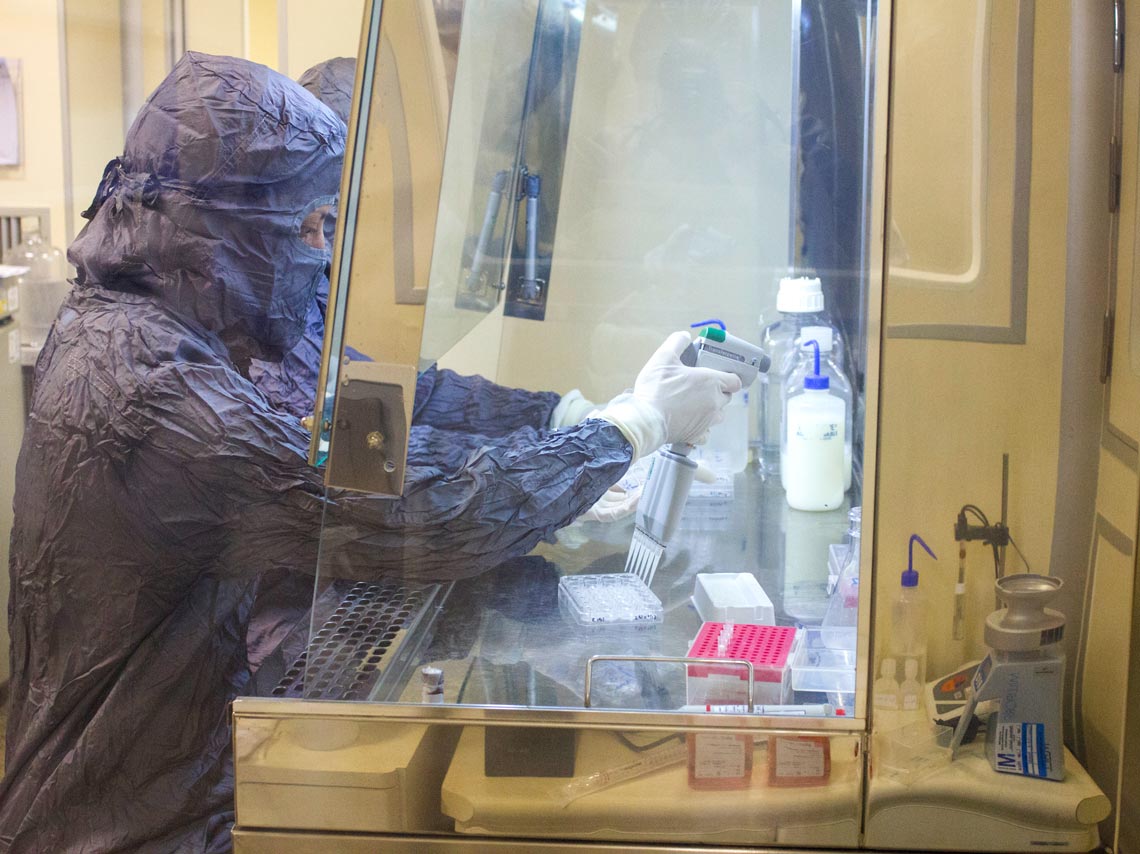

Butantan Institute

A step in the production of the dengue vaccine at ButantanButantan Institute“MSD is now starting Phase 2 studies of its vaccine. We have not yet established which countries and populations we want to include in the Phase 3 trials,” says Leser of Merck. “We hope to recruit significant numbers of people who have been exposed to dengue serotypes—such as type 4—that occurred less frequently in Butantan’s studies.”

The collaboration agreement is mutually beneficial. The advanced stage at which the Brazilian partner’s vaccine program finds itself means the resulting data and experience producing the vaccine can help to accelerate Merck’s program. Conversely, the US company’s experience of developing, producing, and trialing new vaccines can expedite the final manufacturing phase and clinical trials at Butantan. Although based on the same virus preparation engineered at the NIH, the two vaccines will need separate regulatory approval.

The Butantan and MSD vaccines each have different formulations. The Brazilian institute developed a multidose vaccine initially designed for vaccination campaigns such as those periodically organized by the Brazilian Ministry of Health. MSD is looking to serve a more fragmented global market with demand substantially coming from people traveling to tropical areas. The company would therefore focus on production of single-dose vials. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 390 million dengue virus infections occur per year. Should either of the partners in the collaboration decide to shift course, they have agreed to continue to share their experience in production techniques without charging additional royalties.

Sanofi Pasteur/Gabriel Lehto

Sanofi’s Dengvaxia vaccine has limited efficacy and can only be taken by people who have already been infected with the dengue virusSanofi Pasteur/Gabriel LehtoAccording to Covas, the funds provided by MSD can be used toward developing the dengue vaccine and accelerating some stages of the process. “The process of demonstrating the efficacy of the vaccine obviously cannot go any faster, but the process of building and expanding the needed infrastructure can,” says Precioso. Finding the best way to apply the funds will be at Butantan’s discretion. “They will also be used toward development and innovation in general,” he says. The agreement with MSD accommodates potential collaborations involving other vaccines currently produced at Butantan, such as vaccines against hepatitis A and HPV. Through MSD, the institute hopes to tap into global markets, especially in poor and developing countries.

There are still many questions to be explored in the field of dengue research. Alongside the yet-to-be-published general study on the Phase 2 clinical trials, and the ongoing Phase 3 trial, there is other research that is currently being done on the Butantan dengue vaccines. Kallás’s laboratory at USP, for example, is investigating the extent to which the product activates a cellular immune response without involving the production of antibodies. “I hope my research provides an understanding of which immune markers indicate whether a person is protected against dengue, an aspect that currently remains unclear,” explains Kallás.

Project

Dengue: Production of experimental batches of a tetravalent candidate vaccine against dengue (nº 08/50029-7); Grant Mechanism Research for the SUS; Principal Investigator Isaias Raw (Butantan Institute); Investment R$1,926,149.72 (FAPESP/CNPq-PPSUS).