Referenced as a model created in the 1990s, more than 200 public schools were militarized in 2020, totaling close to 500, motivated by the positive results obtained by students in military colleges, a type of institution that has existed in the country since the nineteenth century. Case studies and comparative analyses of student performance both in military colleges and in militarized schools, called civic-military schools, suggest that good performance in these institutions is fostered by factors such as undertaking a selection process, access to larger budgets, better infrastructure, more professionals on staff, and lack of security problems surrounding the facilities.

Having developed research projects since the 1980s in the area of educational policies, psychologist Erasto Fortes Mendonça, from the University of Brasília (UnB), points out that there are different models of military schools for elementary and high school. The most well-known of these brings together schools associated with the Armed Forces, Military Police (PM), or Fire Brigade (CB), as the schools of the Armed Forces or military schools of the Armed Forces (see sidebar on page 78). “They are institutions created to educate young people interested in pursuing a military career,” he explains, recalling that the first military college in the country was founded in 1889 by dom Pedro II (1798–1834) in Rio de Janeiro. At the beginning of the twentieth century, observes historian Marcus Fernandes Marcusso, from the Federal Institute of Southern Minas, Inconfidentes campus, military schools supported by federal funding—from the Ministry of War—dedicated to the children of military officials and those deemed “unfit” to serve. Beginning in the 1930s, these schools began to change, increasing their access to funding and becoming a movement that garnered strength during the military regime (1964–1985),” informs Marcusso, who for seven years has been developing a study about the Escola de Comando e Estado-Maior do Exército (School for Army Leadership and Council) and its teaching guidelines. Today, according to Mendonça, the military schools in Brazil accept students through rigorous selection processes and offer a physical structure and “highly qualified” faculty.

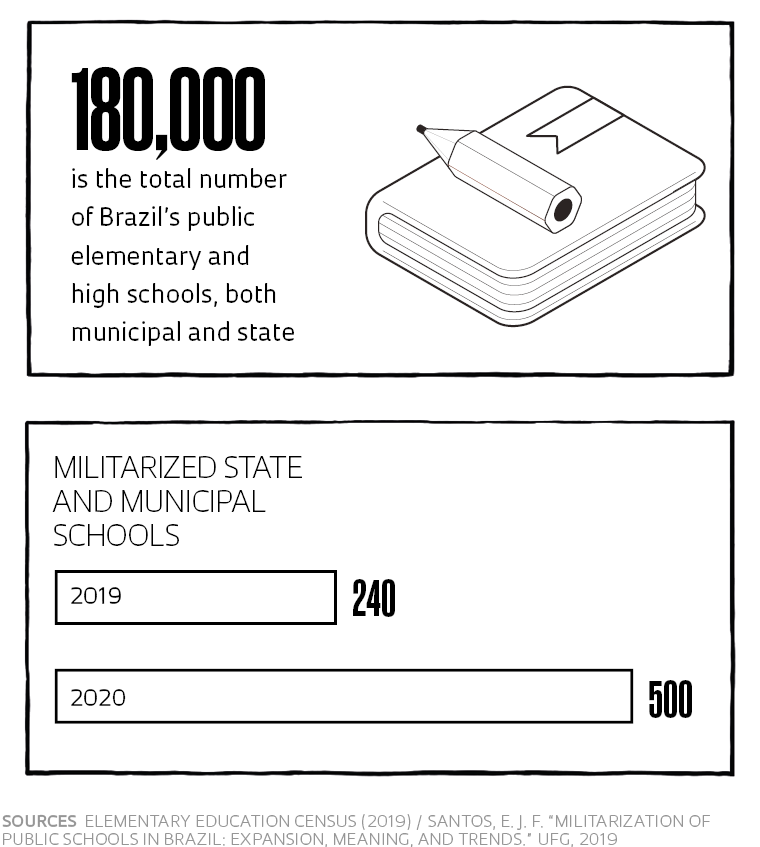

Another type of institution is that of militarized, or civic-military, schools. This militarization incorporates a set of practices and concepts adopted in contexts that do not have the military as a reference point, such as public schools. Overall, the country has 180,000 state and municipal public elementary schools according to the 2019 Primary Education Census, distributed last year. Through partnerships established between the Secretariats of Education and Public Safety of the states, these institutions become managed by officials of the Military Police or the Fire Brigade. “Through these agreements, the officials become responsible for the administration, safety, and discipline of the students, while teachers and coordinators focus on pedagogical matters,” explains Mendonça. According to the researcher from UnB, the partnership model varies by region, but all the schools, once militarized, receive additional funding from the Secretariats of Education or Public Safety and are then able to expand their academic teams.

Militarization

Adoption of a set of practices and concepts characteristic of the military environment in contexts that do not have the military as a reference point, such as public schools

Schools of the Armed Forces

Group of schools dedicated to training cadets

Schools of the Fire Brigade

Accept the children of military personnel and civilians through a selection process

Schools of the military police

Present in 23 states, they accept the children of military personnel and civilians through a selection process

Military schools of the Armed Forces

Elementary education institutions that accept the dependents of

military personnel and civilians through a selection process

Militarized schools

Civic public schools that move to a model of shared management with the Military Police or the Fire Brigade

Military secondary institutions

Institutions maintained by the Armed Forces (Aeronautics, Army, and Marines), the military police, and the fire fighters of some states. They educate officials seeking a career in military sciences

Referencing information shared via the Ministry of Education (MEC) website, militarization facilitates increasing the quality of elementary school education through improvements to the facilities and functioning of the schools, which are carried out through the work of military personnel in the management of administration, teaching, and education. The ministry has also reported on its site, until 2019, the dropout and repetition rates in the militarized schools were, respectively, 71% and 37.4% lower than the averages of other public institutions. The reporters of this edition did not receive a response by deadline from MEC regarding an interview to provide further details and identify studies that were used to promote the civic-military model.

After analyzing the various models adopted by the states to militarize public schools, educator Telma Pileggi Vinha, from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), reports that in Goiás, for example, these institutions are more common in city centers, and the directors tend to be an active official who is recommended by the commander of the Military Police or Fire Brigade. On the other hand, in the Federal District (DF), where militarized institutions are concentrated in the suburbs, the director is from the area of education and the military personnel assume responsibility for internal discipline controls. According to the educator, in the Federal District, the expectation in 2019 was that each militarized school receive R$200,000 more, which would be provided by the Secretariat of Public Safety. Furthermore, about 20 military personnel in the reserve, or who have medical restrictions for working in the field, move to working in the institution. Vinha, who has been studying military schools and civic-military schools since 2018, as part of the work of the Study and Research Group in Moral Education (GEPEM) at UNICAMP, recalls that normally military police and officials who work in militarized schools do not have educational training, with little preparation to work in the school environment. In her opinion, additional funding, which often includes support from the Education Secretariats, makes it possible to improve the physical infrastructure of the institutions, such as adding sports courts, libraries, and laboratories, among other improvements.

Families that agree with the militarized model believe that learning problems can be resolved by increasing discipline

“Officials who are in the reserve or on temporary leave can be contracted to work in military schools. We observed that many who were assigned to these schools in the DF were on temporary leave due to psychological problems, such as depression,” confirms educator Catarina de Almeida Santos from UnB. Data was collected through an information survey carried out by the Militarization Observatory, at the Commission of Defense of Human Rights, Citizenship, Ethics, and Parliamentary Decorum of the Legislative Assembly in the Federal District, of which Santos is a member. “One of the principles of the militarization process is that assigning police to schools does not cause a shortage on the streets. As a result, officials from the reserve or on leave are mobilized,” says the educator, who developed a post-doctoral study on the topic at UNICAMP in 2019.

The first public educational institutions were militarized in Brazil at the beginning of the 1990s in Mato Grosso, Rondônia, and Amazonas. During his master’s dissertation defended in 2019 at the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), Eduardo Junio Ferreira Santos identified that 240 public schools were militarized in Brazil between 1990 and 2019, with 155 of them being state schools and 85 municipal schools. In October 2020, more than 200 public state schools were transformed into civic-military schools in Paraná. According to Vinha, the expansion process of the militarized schools gained strength and visibility with the federal government’s National Program of Civic-military Schools, launched in September 2019 with the objective of militarizing 216 public elementary and middle schools by 2023, with annual funding of R$54 million.

In addition to the presence of officials in the day-to-day management of the schools and an increase in funding, militarization is designed to include military rituals and classes. An example of this is the discipline of Saluting and Signs of Respect, known as CSR. In this course, students learn military songs, hymns, marches, and parades. “Students also switch to wearing different uniform styles depending on the school activities undertaken. The styles and costs vary in each state and municipality, but according to a 2018 survey with a company that provides the uniforms, they can reach a total cost of R$1,500, such as in Piauí,” explains Vinha, adding that the schools in the DF cover the costs of uniforms while in states, such as Roraima and Goiás, families must acquire them, making it difficult for lower income families to access these institutions.

Luli PennaResults from recent studies show that student performance in military schools, that is, institutions created to educate young people interested in a military career, is higher than for those who attend regular public schools. “While the average of the 2017 Elementary School Development Index (IDEB) for the later years of elementary education in public schools was 4.1, in the military schools it was 6.5,” compares Vinha.

Luli PennaResults from recent studies show that student performance in military schools, that is, institutions created to educate young people interested in a military career, is higher than for those who attend regular public schools. “While the average of the 2017 Elementary School Development Index (IDEB) for the later years of elementary education in public schools was 4.1, in the military schools it was 6.5,” compares Vinha.

Another study by researchers at the Federal University of Ceará (UFC), carried out in 2016 and with results published last year, studied data from the state’s Elementary School Continuous Assessment System, comparing the performance of students in regular public schools with that of students attending two military schools in Fortaleza. “We observed a difference in performance between the students who attended the military middle schools in comparison with the average for those in regular middle schools,” shares economist Alesandra de Araújo Benevides, of UFC Sobral campus, one of the authors of the study. According to a member of the Laboratory of Education Data Analysis and Economics (EDUCLAB) at the institution, the research showed that students from military schools acquire a year and a half more of mathematics learning, for example, compared with students from civil institutions.

“There are several extracurricular factors that help explain the higher performance, such as familial characteristics and the selection process used by military schools, which can create a performance bias,” she observes. In the economist’s perspective, the assessed military institutions have higher grades because they use a selection process at the beginning of elementary school such that only students with strong academic performance are admitted. In her opinion, teachers do not tend to be absent in these schools, which guarantees continuity in teaching. Furthermore, the presence of military personnel inhibits the sale of drugs and safety problems in their facilities.

Luli PennaVinha recalls that, according to data from the Anísio Teixeira National Institute of Educational Studies and Research (INEP) of the Ministry of Education, the per student cost in public schools is R$6,000 per year on average, and in the military schools, R$19,000. “These factors sustain the hypothesis that military institutions are privileged with greater financial resources, more professionals, and larger facilities, which positively impact student performance,” argues Vinha.

Luli PennaVinha recalls that, according to data from the Anísio Teixeira National Institute of Educational Studies and Research (INEP) of the Ministry of Education, the per student cost in public schools is R$6,000 per year on average, and in the military schools, R$19,000. “These factors sustain the hypothesis that military institutions are privileged with greater financial resources, more professionals, and larger facilities, which positively impact student performance,” argues Vinha.

The School of Enforcement of the State University of Goiás (UEG) became managed by the state’s Secretariat of Public Safety in 2005. During a scientific study about this process, sociologist Mirza Seabra Toschi, who teaches at the institution and is retired from the Federal University of Goiás (UFG), identified that part of the improvements observed in school infrastructure happened through monthly contributions, “nonobligatory, but strongly encouraged,” of approximately R$130.00 from the students. Payments are collected by the Association of Parents and Instructors, which delivers a payment booklet to families. “Another factor that contributes to the positive results is the socioeconomic characteristics of the families who register their children in this type of institution and who are generally middle or upper class,” he confirms.

Vinha, from UNICAMP, mentions a 2017 study by researchers of UFC who identified that, of the 59 militarized public schools in the Goiás state network in 2017, 36 included families of high or very high socioeconomic status. While in the state public schools, 76% of families received the Family Allowance (Bolsa Família), in the militarized schools, this proportion was 19%. If in the public schools 21% of mothers were uneducated or had not completed elementary school, the proportion for the militarized schools was 3%, according to the researcher. Students who do not abide by the rules or perform poorly are transferred to other institutions. “In Goiás, 20% of students changed schools during the militarization process,” he reports, recalling that militarized institutions do not accept students with special needs nor offer education for youth and adults (EJA) who did not have access to school at the appropriate age.

Similar data were found in a post-doctoral study by Santos of UnB, who analyzed, over the course of a year, regulatory and statutory documents, as well as operational manuals, for militarized institutions in the Federal District. According to the researcher, data from the Militarization Observatory for Schools—created in 2019 by the Commission of Defense of Human Rights of the Legislative Assembly in the DF to follow the trend, receive complaints, and identify management problems—show that 23% of students change schools during the militarization process due to irregular performance or difficulty following rules. “These institutions remove these problems from their daily routine,” he adds.

Vinha recalls that the key legal instruments that guide Brazilian education, such as the Law of Foundations and Guidelines (LDB), the National Base for Common Curriculum (BNCC), the National Plan of Education (PNE), and the Statute of the Child and Adolescent (ECA), advocate that education should foster the development of autonomous and critical thinking individuals. In her opinion, countries that provide a benchmark in education through the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), such as Singapore, Finland, Hong Kong, and Canada, follow the opposite direction than that which the military model proposes for Brazil. “The country’s private elite schools, such as Bandeirantes and Santa Cruz in São Paulo, for example, work with an educational model based on the development of socioemotional competencies, autonomy, participation, confidence, and dialogue,” she compares. According to Vinha, families who agree with the military model are looking for a school that is capable of providing quality education and disciplining students, assuming that the problems with learning can be resolved by increasing rigor and discipline.

“Militarization appears as a response to situations where democratic values and disciplinary resources of the public schools were not sufficient to stop situations involving lack of safety, discipline, and interest, and low-income students,” comments Vinha. According to the researcher, this supports the mistaken hypothesis that leaving discipline and administration to the police allows the teachers to focus on improving education. Vinha believes that the rules of this type of institution include the establishment of strict norms regarding how to dress and behave, not allowing, for example, the use of shorts or loose hair. “In many schools, the police are armed.”

In a study about the militarization of public schools in Bahia, educator Eliana Póvoas Pereira Estrela Brito, from the Federal University of Southern Bahia (UFSB), identified that militarization, upon exercising the disciplinary power of the police within the school, resulted in less misbehavior and violent activity in school life. “The power of the police causes the students to be obedient within the school, but to guarantee the development of peaceful individuals, it is necessary to invest in policies of safety and well-being and not simply divide up the teaching institutions,” she proposes. In Bahia, militarization tends to happen in places of social risk, with high rates of violence and drug trafficking, informs Brito. “In the 2019 study, I tracked the militarization of a school in Santa Cruz Cabrália. When the children left the institution, and knew they were no longer being watched, some quickly abandoned their disciplined behavior from the classroom and began tripping and fighting with their peers,” he recalls.

According to Marcusso, the Federal Institute of Southern Minas, militarization represents an attempt to bring guidelines from military education into public schools. “Military education demands discipline because it aims to develop individuals that will have to order deployments in wars. In the military doctrine, you have to follow rules and not contest them. But to train an official for war is very different from educating a citizen,” he compares. With a similar argument, Sílvio Gallo, from the Faculty of Education at UNICAMP, recognizes the right of families to choose to register their children in military schools, in religious institutions, or technical high schools. “However, the best approach would be to create a parallel network and not invest extra resources into militarizing the regular public school,” he concludes.

Scientific articles

BENEVIDES, A. A. and SOARES, R. B. Performance differential for students in military schools: The case of public schools in Ceará. Nova Economia (New Economy). Vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 317–43. 2020.

BENEVIDES, A. A. and SOARES, R. B. Performance differential for students in military schools: Good students or good school? University Meetings at UFC. Vol. 2. 2017.

BRITO, E. P. P. E. and REZENDE, M. P. Disciplining life begins in school: The militarization of public schools in the state of Bahia. Brazilian Journal of Education Politics and Administration. Vol. 35, no. 3. 2019.

VINHA, T. et.al. Education for the development of autonomy and the militarization of public schools: An analysis of moral psychology. Caderno Flacso on coexistence and violence in schools. In preprint.