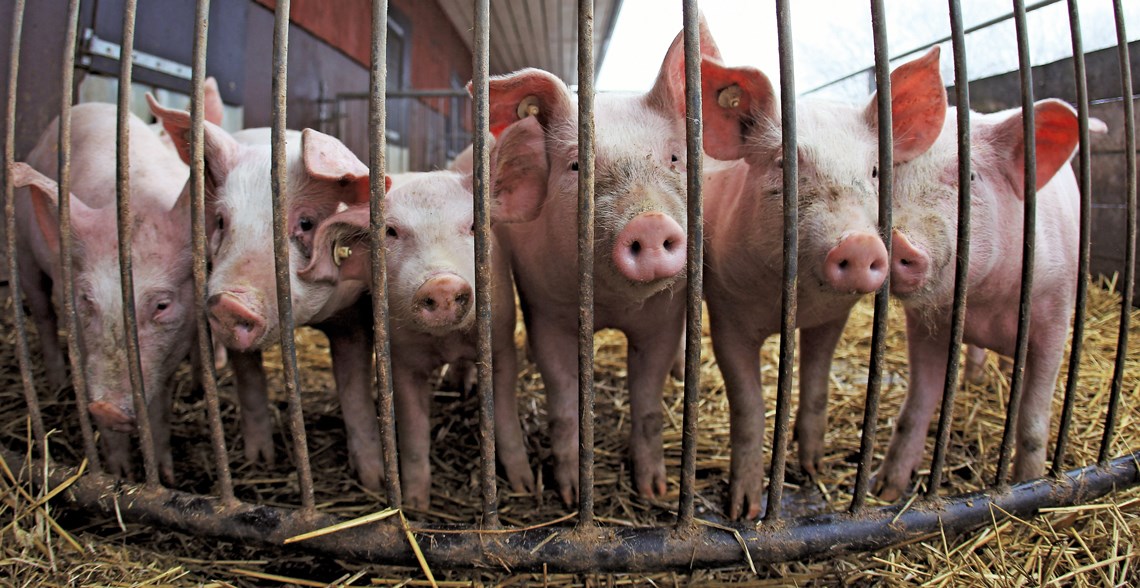

Pig farming impacts the world’s natural resources more than any other food production activity, followed closely by cattle farming. The cultivation of rice and wheat, two crops that are dietary staples in many countries, also have large ecological footprints. Despite providing just 1.1% of the food consumed globally, the exploitation of aquatic resources, especially fishing for shrimp and deep-sea fish, is responsible for almost 10% of food production’s impact on the environment.

Almost half of the world’s environmental footprint is made by six countries: India, China, USA, Brazil, Pakistan, and Indonesia, in that order. The population of this group of nations represents roughly 45% of the 8 billion inhabitants of our planet.

These conclusions are part of a study published in the scientific journal Nature Sustainability in October, which analyzed global food production data from 2017. According to the authors, the raw data used to calculate the impact each food type has on natural resources covered 99% of terrestrial and aquatic food production reported that year by 172 countries. The pressure on the environment was broken down into 36-square-kilometer (km2) regions of the planet. “Many studies point to cattle farming as the food production activity that puts most pressure on the environment. Our work shows something similar,” explains the lead author of the article, American marine ecologist Benjamin Halpern of the University of California, Santa Barbara, in an interview with Pesquisa FAPESP. “The high impact of pig farming and rice and wheat cultivation was unexpected. But it was identified because we looked at the combined influence of multiple forms of environmental pressure arising from the total volume of food produced.”

Most studies calculating the carbon footprint of agriculture and fishing tend to focus on carbon dioxide (CO2), the most significant greenhouse gas. Some also consider methane (CH4), which is the second greatest contrinutor to global warming. Including methane emissions is particularly important when analyzing the carbon impact of beef and dairy farming. Ruminants release significant amounts of methane due to part of their digestive process known as enteric fermentation.

But when three other types of environmental impact caused by food production are evaluated (use of fresh water, activities that reduce species biodiversity, and pollution generated by agricultural inputs) alongside the traditional carbon footprint calculations, the pressures of pig farming slightly exceed those of cattle farming worldwide, according to the article. There are approximately 800 million pigs in Brazil, compared to around one billion head of cattle. “The level of influence each type of pressure has on the environmental footprint varies depending on the type of food produced and the country in question,” says Halpern.

Johannes Eisele / AFP via Getty ImagesExploitation of aquatic resources generates 1.1% of food, but almost 10% of the global environmental footprintJohannes Eisele / AFP via Getty Images

Greenhouse gas emissions account for 60% of the environmental pressure of cattle raising. In pig farming, its weight is about four times smaller. According to the study, most of the environmental impact of pig farming derives from pollution associated with the use of nutrients given to animals. In wheat and rice cultivation, the biggest contributor is the intensive use of water and disturbances to local biodiversity.

The environmental footprint generated by a country’s food production is roughly proportional to the size of its population. Some nations with major livestock and agricultural industires, such as the USA and Brazil, generate relatively greater pressure on natural resources than would be expected for their population density. The opposite is true in China and India, the two most populous countries in the world. The two Asian nations each represent 17% of the global population but account for less than 15% of the world’s environmental footprint from food production.

According to the article, human food production uses half of the planet’s habitable area and 70% of its fresh water. It generates between a quarter and a third of manmade greenhouse gases, in addition to polluting drainage basins and coastal areas with nutrients. “As well as greenhouse gas emissions, the issue of water use in agriculture is an extremely important current topic,” says Jean Ometto, an agronomist from the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and one of the coordinators of the FAPESP Research Program on Global Climate Change (PFPMCG), who did not participate in the study. “In Brazil, irrigation is only still used in a few regions dedicated to agriculture. But in some places there has been a significant expansion of irrigated area.”

Carlos Eduardo Pellegrino Cerri, an agronomist from the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture at the University of São Paulo (ESALQ-USP), stresses the importance of research on the environmental footprint of food production. “It’s a very important and current issue,” says Cerri. He argues, however, that scientists should start using the concept of carbon balance (which accounts for greenhouse gas absorption as well as emissions) when calculating the carbon footprint of agricultural crops, instead of of only taking emissions into account. “Using the carbon balance would be more accurate, since a well-managed crop can even absorb more carbon than it emits.”

In a field study carried out at three soy farms in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul in 2020/2021, Cerri found that through corrective practices and the proper use of fertilizers, the producers could prevent up to 77% of their carbon emissions. If the approach were to be adopted on a wide scale, soybean farming would capture more carbon than it emits, especially in the soil, according to the ESALQ researcher.

Scientific article

HALPERN, B. S. et al. The environmental footprint of global food production. Nature Sustainability. Oct. 24, 2022.