Catirina – Listen, Mané, I already told you I don’t want to. No means no!

Mané – I like it when you play hard to get…

Catirina – Wow, do you want it that bad? Wait there—I’m going to get my friend Da Penha. Together we can sort this out.

(Catirina leaves the scene)

Mané – Oh the pressure… Two young ladies, oh my.

(Catirina enters the scene with a bat and hits Mané on the head, and he falls inside the booth)

This is an excerpt from a show by Catarina Araújo de Medeiros, known as Catarina Calungueira, a puppeteer from Seridó, a semiarid region of Rio Grande do Norte. The reference to the Maria da Penha Law, which protects women from domestic and family violence, would have been unthinkable in traditional northeastern puppet shows a few decades ago. But today it reflects modern reality. Medeiros ventured into a male-dominated world and, together with other artists, she is reshaping performances, ensuring that audiences still identify with the stories and characters.

The history of this reinvention is covered in Teatro de bonecos popular potiguar (Popular puppet theater from Rio Grande do Norte; Editora Escribas, 2025), a book by André Carrico, from the Arts Department at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN). The book, which was based on eight years of research, tells the stories of 11 puppeteers—two women and nine men—from among 55 he documented in the state. By publishing their biographies, Carrico offers readers a glimpse into the popular tradition that has spanned centuries after establishing itself in the Brazilian Northeast at an unknown date. It is also not known when the art form arrived in Brazil. “One hypothesis is that the first puppets were brought over by Jesuits in the sixteenth century, used as pedagogical tools to convert Indigenous people,” says the researcher.

Over the years, the art of making puppets—whether glove puppets, rod puppets, or even full costumes—has been adapted in Brazil. Amerindian features and African references helped shape their appearance and accessories. At the same time, the classics of Iberian comedy were mixed with popular reinterpretations of literary tradition. “A distinct dramaturgy was thus established in each of the nine northeastern states,” says Carrico.

Though they are known by different names across the region—mamulengo in Pernambuco, João Redondo in Rio Grande do Norte, babau, cassimiro coco, calunga, and others elsewhere—the performances revolve around recurring figures. They always feature a poor Black man, an authoritarian captain, an untamable ox, and often fantastic creatures, such as ghosts or the boogeyman figure known as Papa-Figo.

The common thread is humor—whether comical, ironic, or caustic—used to highlight injustice and to deconstruct hierarchies. “However, sexist, homophobic, and racist jokes were also common in the past,” notes Carrico. “Not because they were intrinsic to puppet theater, but because that was how society viewed the world. The humor simply mirrored prevailing customs.”

Cícero Oliveira | Pedro Lucas RebouçasTwo generations of puppeteers from Seridó: from the left, Dona Dadi and Catarina CalungueiraCícero Oliveira | Pedro Lucas Rebouças

Changes began in the late 1980s, when Maria Iêda Silva Medeiros (1938–2021) decided, at age 50, to become a puppeteer in Carnaúba dos Dantas, Rio Grande do Norte. Known as Dona Dadi, she avoided swearing in her performances. “It was a huge change that paved the way for much younger women, like Catarina Calungueira,” says Carrico. Now, at the age of 32, Catarina is involved in a network of female puppeteers in Rio Grande do Norte called Rede de Bonequeiras, which she helped create in 2019. “Crude jokes are disappearing from performances and it is clear that they cause discomfort even among the oldest puppeteers,” says the researcher.

Fights on stage, as a form of humor, are still common. Nowadays, knife fights are rare, but clubs and sticks still feature prominently. “These props are not unique to Brazilian puppetry. They appear in commedia dell’arte [Italian popular theater that flourished in the sixteenth century] and in Turkish shadow theater from the fourteenth century,” explains Carrico, who is currently doing postdoctoral research at the University of Bologna, Italy, on the similarities between northeastern Brazilian and Italian folk puppets.

The violence of these shows once drew criticism from Helena Antipoff (1892–1974), a Russian psychologist and educator who migrated to Brazil in 1929 to work at the Minas Gerais State Department of Education. Shortly thereafter, in 1932, she founded the Pestalozzi Society in Belo Horizonte to assist physically disabled and socially vulnerable children. In the 1940s, she moved to Rio de Janeiro and took the society nationwide.

“During her academic training in Europe, she saw that puppet theater was an important pedagogical tool,” explains historian Tânia Gomes Mendonça, author of the book Entre os fios da história, uma perspectiva do teatro de bonecos no Brasil e na Argentina (1934-1966) (Between the threads of history, a perspective on puppet theater in Brazil and Argentina, 1934–1966), published by Paco Editorial last year. The book was the result of her doctoral thesis, defended in 2020 at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP).

Antipoff had a very clear educational mission: puppets should convey positive messages to children, aid in learning, and teach them about good and evil. “She was aligned with the principles of the New School, a movement that emerged in Europe and the US in the nineteenth century and gained momentum in Brazil in the early twentieth century. The pedagogical approach aimed to help students learn through direct experience rather than rote memorization,” says the historian. Direct experience could mean planting beans and watching them grow, or making puppets through which to tell their own story.

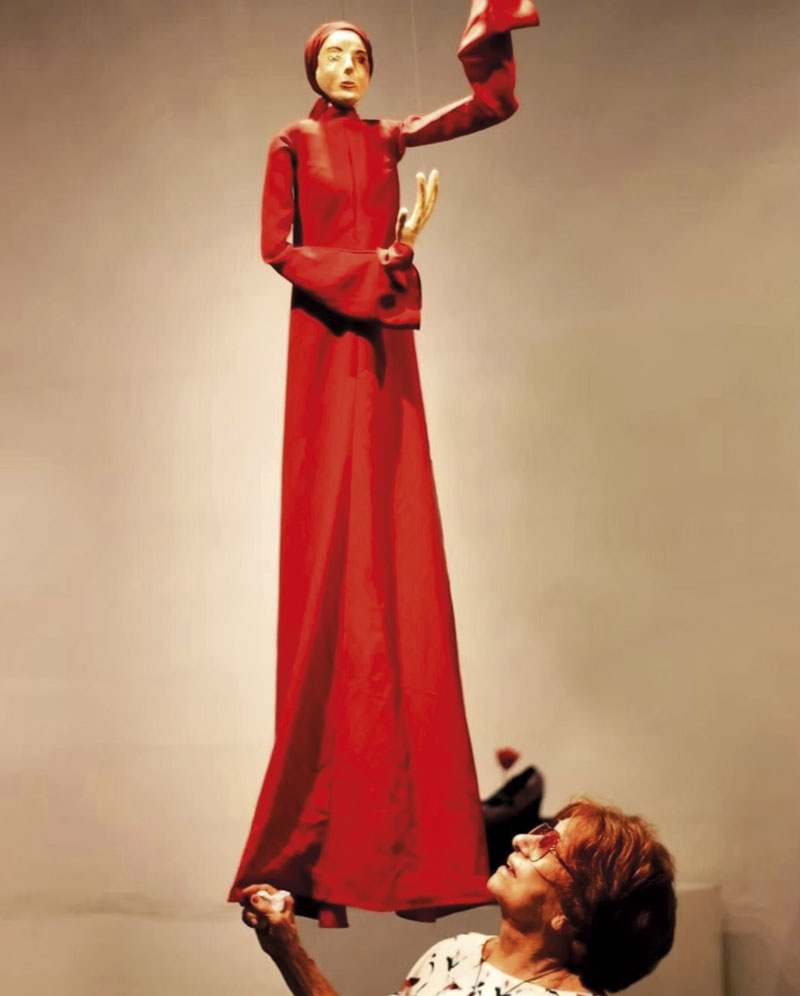

Berenice Farina da Rosa Puppeteer and researcher Ana Maria Amaral with one of her creationsBerenice Farina da Rosa

From the 1940s onward, she organized courses, encouraged the publication of books on the subject, and developed a network of teachers, art educators, and playwrights She was the driving force behind an attempt to professionalize puppet theater, which had never been done in Brazil, according to Mendonça. In the 1940s, as part of the first puppet theater course for adults offered by the Pestalozzi Society of Brazil, students created puppets that they used to put on a performance of Auto de Natal (Christmas Play), written by the poet Cecília Meireles (1901–1964). “The play combined traditional European puppetry with the knowledge that the course participants were beginning to acquire about Brazilian performances,” says the historian.

This approach was in sharp contrast to the popular puppetry of the Northeast. “The texts were not open to improvisation and were didactic in nature: encouraging children to root for morally upright characters or to practice good hygiene, for example,” says Mendonça.

In her thesis, she compared Antipoff’s career to that of Argentine puppeteer Javier Villafañe (1909–1996), one of the most influential figures in Argentine and Latin American puppetry. The performer was part of Argentina’s first generation of modern puppet theater, formed in the 1930s and influenced by Spanish poet and playwright Federico García Lorca (1898–1936), who moved to Buenos Aires in 1933. Villafañe was introduced to Lorca and was inspired by his puppet theater performances.

In 1941, Villafañe visited Brazil with his puppets, and although he participated in educational missions, his work differed from that of the Pestalozzi Society. “In Brazil, the New School became a state project at the beginning of the Vargas government in the 1930s. But the same was not true in the neighboring country of Argentina, and this meant that Argentine puppeteers had more independence in their creative processes,” explains the historian. “Children’s theater there retained mischievous, cunning, and malicious characters, such as Pedro Urdemales, the counterpart to Brazil’s Pedro Malasartes.”

The division of performing arts by age group only began in the late nineteenth century. Until then, children attended the theater and opera with their parents, and puppets addressed audiences of all ages. Although puppetry is now commonly associated with children, it originally explored adult themes and possibilities beyond what human actors could achieve. “For a puppet, there are no limits. That is both fascinating and unsettling for artists and audiences alike,” says Wagner Cintra, a professor at the Institute of Arts of São Paulo State University (UNESP), São Paulo campus.

Rafael MarquesScene from the show Caminhos de Violeta, by Daiane BaumgartnerRafael Marques

A scholar of puppetry for 25 years, Cintra has conducted research with funding from FAPESP on Ana Maria Amaral, a pioneering puppeteer and researcher. Born in São Paulo in 1931, Amaral earned a degree in library science in the 1950s and also pursued poetry. At the end of the 1950s, she spent some time in the US, where her father lived at the time. “It was through her contact with people linked to the counterculture movement, especially the beatniks, that she became involved with puppet theater,” says Cintra.

When she returned to Brazil in the 1970s, Amaral became a professor on a new puppet theater course started in 1975 at USP’s School of Communication and Arts (ECA). She remained at the university until 2014. In 1976, she founded Casulo – Centro Experimental de Bonecos (Casulo Experimental Puppet Center), later renamed Casulo BonecObjeto. Some of her shows, such as Palomares (1978), were performed in other countries, such as Iran and Mexico.

According to Cintra, the puppeteer became a central figure in the development of animated theater in Brazil by introducing it into academia. Amaral even coined the term “theater of animated forms.” “This conceptual umbrella encompasses performances involving puppets, shadows, and other objects, among other forms in which inanimate and human elements interact on stage,” explains the researcher.

In 2023, Cintra published an article titled “Periferias de re(in)novación del teatro de títeres en Brasil – Un corte de São Paulo” (Peripheries of re(in)novation in Brazilian puppet theater – A case study of São Paulo), in which he analyzed contemporary sources of innovation in puppetry: two groups called Talagadá (from Itapira) and Teatro Por um Triz (from São Paulo), and two artists called Daiane Baumgartner (from Rio Claro) and Juliana Notari (from São Paulo).

Baumgartner, for example, uses several techniques, including a hybrid puppet partly worn by the performer. That is what she uses to perform Caminhos de Violeta (2023), a play about aging. “Reflecting on this theme through her own experiences and those of her mother and grandmother, Daiane is not so much focused on bodily transformation as on her place as a woman in the world,” says Cintra. “And through the puppet Violeta, she expresses things beyond words.”

The story above was published with the title “Giving voice to forms” in issue 355 of September/2025.

Project

Ana Maria Amaral’s cocoon: A journey into the heart of the inanimate (nº 19/19062-2); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Wagner Francisco Araujo Cintra (UnEsp); Investment R$10,370.95.

Scientific article

CINTRA, W. “Periferias de re(in)novación del teatro de títeres en Brasil: Un corte de São Paulo“. In: 5. Encuentro Teórico Teatral Internacional Ensad. Lima, Peru: Dossiê Ensad, 2023.

Books

CARRICO, A. Teatro de bonecos popular potiguar. Natal, RN: Editora Escribas, 2024.

MENDONÇA, T. G. Entre os fios da história ‒ Uma perspectiva do teatro de bonecos no Brasil e na Argentina (1934–1966). Jundiaí, SP: Paco Editorial, 2024.