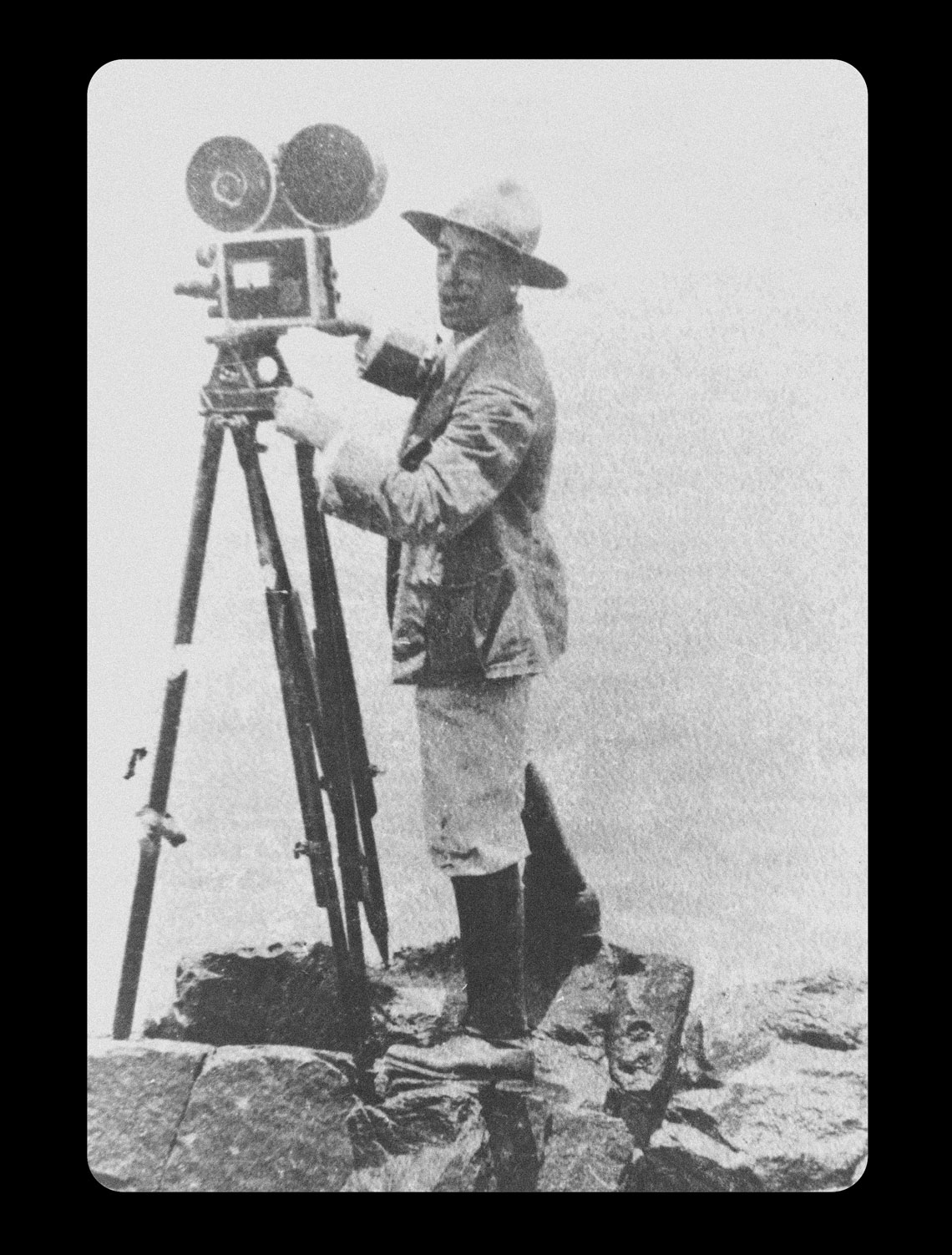

Amazon Museum / Federal University of AmazonasSantos on the Madeira River in Rondônia, 1921: it is estimated that the filmmaker directed more than 90 films, most recorded in the Amazon regionAmazon Museum / Federal University of Amazonas

At 6:21 p.m. on February 7, 2023, Sávio Luís Stoco, a researcher from São Paulo, received an email. “Dear Dr. Stoco,” began the message from American critic and curator Jay Weissberg, director of the Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, a silent film festival held annually in Italy. After apologizing for writing in English, Weissberg explained why he was getting in touch. “A little earlier today, one of the curators of Czech’s National Film Archive in Prague sent me a film that I believe may be of interest to you.”

Cataloged in the Czech Republic as a 1925 American production named Wonders of the Amazon River, the 35-millimeter (mm) feature film was indeed of great interest to Stoco. For his doctoral research, defended at the School of Communications and Arts of the University of São Paulo (ECA-USP) in 2019, he analyzed the film, whose original title is Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo (Amazon, the longest river in the world; 1920), and another feature film, No Paiz das Amazonas (In the country of the Amazons; 1922).

Both films were directed by Portuguese Brazilian Silvino Santos (1886–1970), considered one of the most prolific nonfiction filmmakers in Brazil at the beginning of the twentieth century. It is estimated that he made eight feature films, five medium-length films, and 83 shorts, mostly recorded in the Amazon region in the 1910s and 1920s. However, while a copy of No Paiz das Amazonas was kept safely at the Cinemateca Brasileira archive in São Paulo, Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo was considered lost, achieving an almost mythical status in Santos’s filmography.

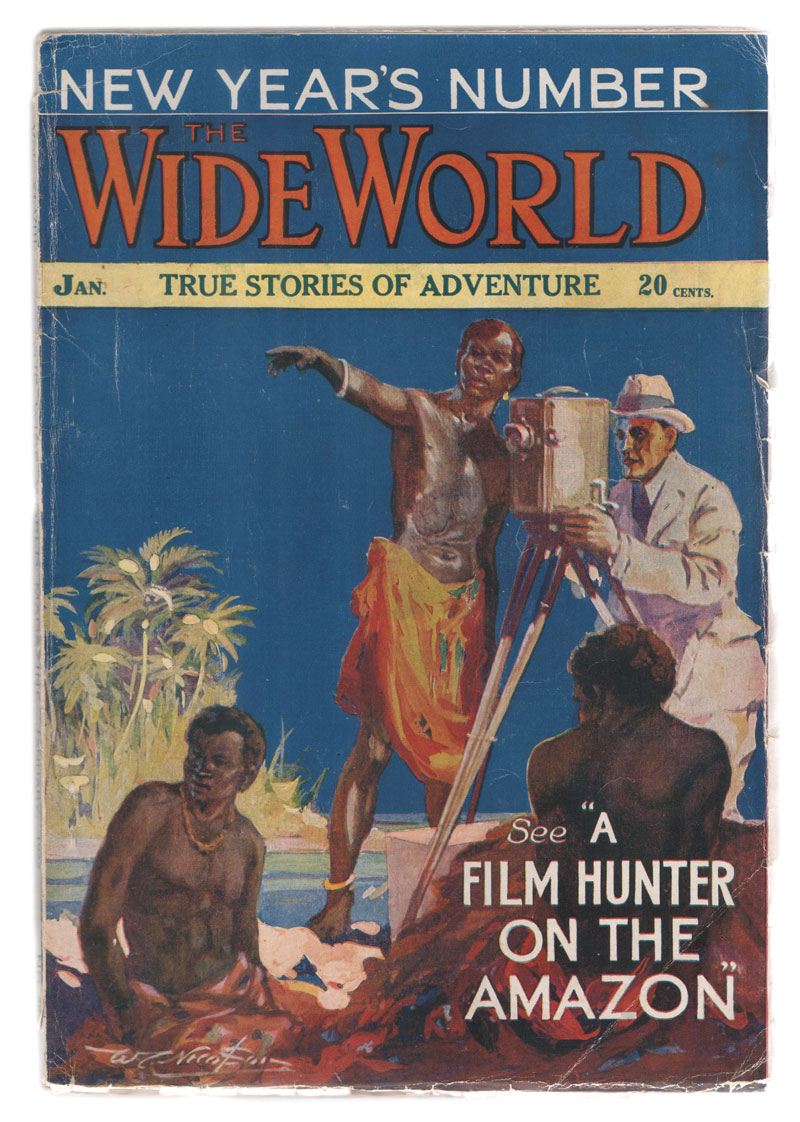

Familiar with Santos’s cinematographic language, Weissberg suspected that the film had been mistakenly credited to somebody else. After searching online, he found Stoco’s thesis and contacted the researcher. In Stoco’s work, he reconstructed Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo using more than 130 photographs from two reports about the film published in popular science magazines Wide World (UK) and Sciences et Voyage (France) in the 1920s. “It was a great surprise to receive that email. I had no hope that this film would ever be found,” recalls Stoco, now a professor at the School of Visual Arts of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). “Silvino himself wrote in his autobiography [O romance de minha vida (The romance of my life), 1969], which remains unreleased, that the film was ‘in the orbit of the planets.’”

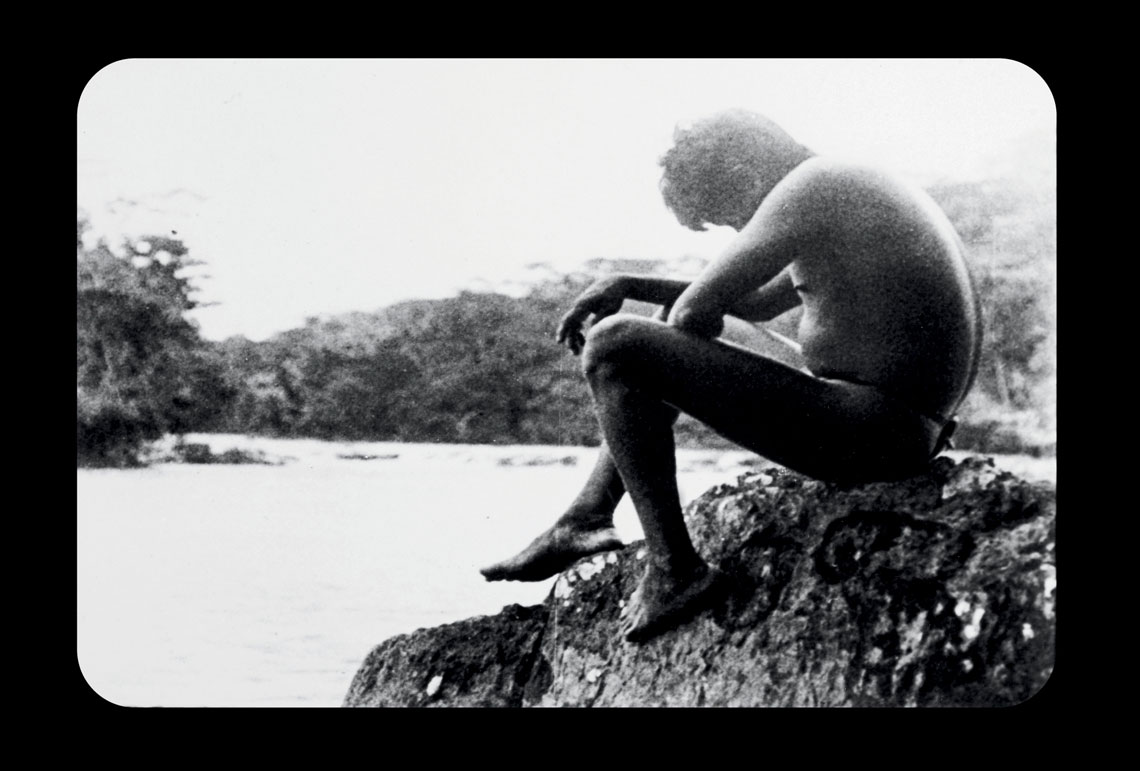

Cinemateca Brasileira ArchiveA still from the film No Paiz das Amazonas (1922)Cinemateca Brasileira Archive

Weissberg also got in touch with the Cinemateca Brasileira archive, which is home to much of the filmmaker’s work. The institution analyzed the recording and confirmed that it was Santos’s lost film. The joint effort was the final chapter in a story that spanned more than a century.

Colonial outlook

Born in Cernache do Bonjardim, Portugal, Santos moved to the North of Brazil in 1900, at the age of 14. His brother Carlos, a trader with stores in Belém and Manaus, already lived in the region. “Silvino was from a wealthy family in rural Portugal and came to Brazil in search of adventure. His childhood dream was to visit the Amazon,” explains Selda Vale da Costa, a retired anthropology professor from the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM). Costa wrote one of the first academic papers on Santos: her master’s thesis “Eldorado das ilusões – Cinema e sociedade – Manaus (1897–1935)” (Eldorado of illusions – cinema & society – Manaus [1897–1935]), defended at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP) in 1987.

Based in Manaus, Santos tried his hand at photography and painting before he got into cinema. “In 1913, he was hired by businessman Júlio Cesar Arana to make a film in Peru,” says Eduardo Morettin, a historian from the Department of Cinema, Radio, and Television at ECA-USP who supervised Stoco’s thesis. Arana worked in the Peruvian rubber sector and was the founder of the Peruvian Amazon Company. “At the time, the entrepreneur was facing legal proceedings in England and the objective of the film was to discredit accusations that he and other businessmen in the Putumayo River region were involved in exploiting, torturing, and killing Indigenous people,” adds Stoco.

Despite these less-than-noble motives, Santos agreed to produce the film. Before starting, he was sent to France to buy equipment and take film courses. According to Stoco, the film was completed but failed to fulfill its purpose because the boat taking it to England sank. “Remaining fragments were used in later productions, including in Amazon, the longest river in the world and In the country of the Amazons,” says the researcher.

Cinemateca Brasileira ArchiveA still from No Rastro do Eldorado (1924)Cinemateca Brasileira Archive

Shortly afterwards, Santos was named head of the cinematographic division of Amazônia Cine-Film, a production company founded by local businessmen in 1917, with funding from the Amazonas government. According to Stoco, the company made 12 short films, all directed by Santos. “These films were like newsreels, covering shipwrecks and inaugurations of public institutions, for example,” says the researcher.

His biggest project, however, was Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo. “It was Silvino’s own idea. He wanted to travel more in the Amazon and record images of the region,” says UFAM’s Costa. “But the project also satisfied the goals of these entrepreneurs and the Amazonas government. They wanted to separate the state’s image from rubber extraction and show that there were other economic possibilities in the region, such as livestock farming and agriculture.”

Recorded intermittently between 1918 and 1920, the film portrays a journey along the Amazon River and its tributaries, with shooting taking place in locations such as Amapá, Pará, and Amazonas. It includes scenes of a row of dead manatees, which are now threatened with extinction, and Indigenous people from the Uitoto ethnic group in Peru. “These are records of colonial imagery—they do not deviate from the norms of the time. Indigenous people, for example, are seen as ‘the other,’ the object of the white man’s ‘civilizing’ efforts, representing something to be conquered,” explains Morettin.

According to Costa, it is important to analyze the filmmaker’s work in light of the context of the time. “He did not make any effort to look critically at the situation,” points out the researcher. “But at the same time, due to the financial support of these businessmen, Silvino had access to cutting-edge equipment and artistic freedom. He was thus able to contribute, in aesthetic terms, to the language of Brazilian cinema. Not to mention that his films are period documentaries that show aspects such as the types of housing from the time, among other things.”

Sávio Stoco ReproductionThe cover of an issue of Wide WorldSávio Stoco Reproduction

Another of the filmmaker’s qualities, according to Costa, was his fearless spirit. “Silvino wasn’t afraid of going into the jungle to film,” says the anthropologist. Brazilian architect and geographer Luciana Martins, a professor of Latin American Visual Cultures at Birkbeck College, University of London, agrees with her. “In my research, I found a photo of Silvino working in a laboratory set up in the middle of the rainforest, inside the trunk of a tree,” says Martins, who analyzed the filmmaker’s work in articles and books such as Photography and Documentary Film in the Making of Modern Brazil (Manchester University Press, 2013).

Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo was completed in 1920. At this point in the story, Propércio de Mello Saraiva entered the scene. “He taught typing and other writing techniques in Manaus, and he was engaged to the daughter of the Amazonas Commercial Association’s accountant, Avelino Cardoso, the same person who wrote the film’s title cards,” says Stoco. “As a result, Propércio was tasked with taking the film to Europe, having it translated into English, French, and German, and then marketing it. When he got there, however, he stopped contacting Santos and Amazônia Cine-Film.”

Santos wrote in his autobiography that Saraiva pretended that he directed the film himself in order to steal the profit. Titled As maravilhas do Amazonas (The wonders of the Amazon), the film was screened in countries such as France, England, and Poland. Meanwhile, in Brazil, the film’s disappearance led the production company Amazônia Cine-Film to bankruptcy.

Santos, however, did not stop filming. His most famous title was No Paiz das Amazonas, a 1922 production funded by Portuguese businessman Joaquim Gonçalves de Araújo (1860–1940), known as J.G. Araújo. “The film was designed as propaganda for Commander Araújo’s companies, which included rubber plantations, warehouses, and cattle farms, and was screened as a showcase for these businesses at the International Exhibition of the Brazilian Independence Centenary, held in Rio de Janeiro in 1922 and 1923,” says Morettin, who studied the event with funding from FAPESP. “The judges awarded it the gold medal and it was shown in Rio de Janeiro for a five-month run,” continues Morettin.

Cinemateca Brasileira ArchiveA still from the feature film Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo (1920)Cinemateca Brasileira Archive

During his time in Rio de Janeiro—totaling about a year—Santos filmed what he saw in exhibition halls and beyond. “He walked around the city with his camera and recorded everyday life in Rio,” says Martins, from the University of London. “Then he edited the scenes together into a quick, modern montage that included close-up shots. This was in great contrast to other films of the time that looked more like photo albums, with slow pans.” Some of these images can be seen in Fragmentos da Terra Encantada (Fragments of an enchanted land; 1971), a documentary by Roberto Kahane and Domingos Demasi made with what was left of Santos’s Terra Encantada (Enchanted land; 1923). Another of the filmmaker’s works is No Rastro do Eldorado (In the wake of Eldorado; 1924), which followed an expedition from Manaus to Venezuela led by American geographer Hamilton Rice (1875–1956) in the 1920s. “It is believed to be the first film with aerial images of the Amazon,” says Costa, from UFAM.

Between 1927 and 1929, Santos spent time with J.G. Araújo’s family in Portugal, directing films such as Terra Portuguesa: O Minho (Portuguese land: Minho; 1934). The family then returned to Manaus together with the filmmaker. “From the 1930s onwards, his film production became more sporadic, mostly consisting of films made for his bosses,” continues Costa. “Santos started working for J.G. Araújo in the early 1920s, heading the group’s audiovisual arm, which was shut down in the 1940s. But he remained an employee of the company in Manaus until the end of his life. Among other things, he worked in marketing and product design. Finally, he managed the company’s warehouses.” According to Costa, the filmmaker, who passed away in 1970, was largely forgotten in the city until shortly before his death, when he was honored at the First Brazilian Film Festival in the North in 1969.

After premiering in October 2023 at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, an Italian event organized by Weissberg, Amazonas, Maior Rio do Mundo was screened in the Czech Republic. The following month, it was shown in Brazil for the first time at the Cinemateca Brasileira in São Paulo. In February 2024, it was Portugal’s turn. According to the agreement with the Czech Republic’s National Film Archive, the film will remain in Prague, while the Brazilian institution will be responsible for screening it around the country. In addition to the São Paulo state capital, a digitalized version of the film was also screened in João Pessoa, Rio de Janeiro, Fortaleza, Belém, Brasília, and Manaus.

In Manaus, UFAM’s Amazon Museum is home to a small Santos collection that includes 150 photos on glass negatives (used for photographs before acetate), two 35 mm films (a copy of No Paiz das Amazonas and another untitled recording of Manaus and surrounding areas), and tools used by the filmmaker, such as a developing tray. In the coming months, the museum intends to make Santos’s unpublished autobiography, in which he laments having seen his film lost “in the orbit of the planets,” available on its website.

Book

STOCO, S. L. O cinema de Silvino Santos (1918–1922) e a representação amazônica: História, arte e sociedade. Manaus: Fundo Municipal de Cultura, 2021.