National Archive / Correio da Manhã Fund

The novelist in 1904National Archive / Correio da Manhã FundEvery poet who becomes a classic was initially considered strange and unique, argues US critic Harold Bloom in his famous 1973 book The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. Machado de Assis (1839–1908), who was also a poet, seems to fit this definition well. Now considered central in Brazil’s literature, the Rio de Janeiro author had his talent immediately recognized by his contemporaries; however, they initially classified him as a unique case, displaced from the local literary milieu. In his research analyzing the reception of the author’s work, Hélio de Seixas Guimarães, from the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP), describes how it was only in the 1950s that writers and critics began incorporating Assis into modern heritage.

Guimarães explains that, between the mid-nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the Brazilian writers that were valued most were those who featured the so-called “local color” in their works, as well as realist and naturalist authors who were committed to directly representing the social, economic, and political situation of the country. In this sense, Guimarães evaluates, Assis was not in line with his contemporaries, “as he did broach these topics, but in a different, almost always deeper and more subtle way.” “Critics of the time claimed that, as a writer, he was concerned with analyzing what goes on inside the characters, leaving aside, for example, descriptions of nature and customs, which were common for other writers of the period,” he clarifies. Pioneer critics, such as Silvio Romero (1851–1914), José Veríssimo (1857–1916), and Araripe Júnior (1848–1911) argued that Assis should be analyzed as an isolated case in local literature, and that the humor in his novels placed him closer to the British tradition. “When writing about the history of Brazilian literature, Romero mentioned Assis in footnotes; Veríssimo, on the other hand, dedicated a chapter exclusively to his work, apart from studies on other authors from the same period,” says the researcher.

The recognition of Assis’s talent, coupled with his nonconformity to the characteristics that marked Brazilian literature in the early years of the twentieth century, resulted in his being seen as an academic writer, attuned to traditional values and concerned very little with reflecting on national identity. It is also for this reason that modernist authors, such as Mário de Andrade (1893–1945), Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902–1987), and Monteiro Lobato (1882–1948) were ambivalent in their analyses of his work. “To them, Assis was a difficult figure to swallow. Mário de Andrade, for example, wrote that he admired Assis, but did not love him,” reports the researcher. As literary critic Ieda Lebensztayn points out, modernist writers sought to break new ground in national literature by taking a stand against previous trends. In this context, Assis—who founded the Brazilian Academy of Languages (ABL) in 1897—was considered a negative influence, as he did not make an effort to subvert previous movements and “lived comfortably as a bourgeois government official,” in the words of Mário de Andrade. “Andrade had reservations about the fact that Assis was never outspoken about his mixed race status and preferred instead to adopt British customs. At the same time, he admired Assis’s dedication to art and his potential as a critic,” says Lebensztayn.

She reveals that Monteiro Lobato, however, when analyzing the artistic consequences of Assis’s social trajectory, stated that his humble origin and social ascension allowed him to write about the social stratification of the country in a perfectly intuitive way. But they also motivated him, in practice, to cultivate his own class isolation, leading him to found the ABL, for example—an arena exclusive to the intellectual elite. Lebensztayn is coediting, along with Guimarães, a book that features the collected reactions of 34 writers, from 1908 to 1939, to the figure and work of Machado de Assis. “He is a reference point for every fiction writer, with elements they want to either emulate or distance themselves from in the construction of their own identities,” explains the researcher.

Still regarding the modernist writers, Guimarães reports that the development of Drummond’s relationship to Assis is representative of that of other authors. “I gathered texts in which the poet, over the course of six decades, deals with the rather uncomfortable figure of Assis, whom he repudiated in his youth but came to fully love when older,” reveals the researcher, who examines the specific case of the Minas Gerais poet in the book Amor nenhum dispensa uma gota de ácido – Escritos de Carlos Drummond de Andrade sobre Machado de Assis (No love goes without a drop of acid: Carlos Drummond de Andrade on Machado de Assis; Três Estrelas, 2019). To illustrate this, he recalls that Drummond dedicates to his predecessor the 1958 poem A um bruxo, com amor (To a wizard, with love), considered one of the most significant tributes from one writer to another in Brazilian literature. “In writing this poem, Drummond seems to fully incorporate Assis into his own poetry,” he notes.

In the late 1950s, Drummond also led a campaign against the ABL’s project to build a mausoleum where Assis’s remains—then buried in a Rio de Janeiro cemetery—would be transferred. “Drummond argued that this would represent a kind of retrogression to the place Assis occupied in the decades after his death, when he was thought of as an academic writer and a stranger to the local literary environment,” he says.

Brazilian Academy of Languages

Writers carry Machado de Assis’s coffin out of the Brazilian Academy of Languages in 1908Brazilian Academy of LanguagesPublications in periodicals

As part of the process of revisiting his literary journey, new facets of Assis have also been revealed through the analysis of texts that were considered minor until the mid-2000s. Silvia Maria Azevedo, from the School of Sciences and Languages of São Paulo State University (FCL-UNESP), Assis campus, in two books published last September as a result of her research paper A colaboração de Machado de Assis na Semana Ilustrada (Machado de Assis’s contributions to Semana Ilustrada), has recognized and gathered his chronicles that were published in the magazine between 1869 and 1876, under the pseudonym “Dr. Semana” (Dr. Week). “Up until then, it was thought that Dr. Semana was a collective pseudonym and that only a few of the texts were Assis’s. However, I found that all of them were written by him,” she reveals.

According to Azevedo, this discovery was made possible through the analysis of stylistic resources used by Assis, which were also present in the chronicles of Dr. Semana. In one of them, “crítica às avessas” (criticism turned on its head), the author praised certain literary references considered to be of low quality. “Claiming things opposite to what he truly means, in an ironic tone, is typical of Assis,” she reports. Azevedo also mentions the frequent quoting of playwrights William Shakespeare (1564–1616) and Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, or Molière (1622–1673), as another element that aids in proving his authorship of the chronicles. In line with Guimarães’s analyses, Azevedo indicates that the chronicles reveal Assis’s involvement with issues of his time. “They prove that the criticisms of his contemporaries about his supposed indifference to the political and social reality of Brazil were unfounded,” she argues.

Lúcia Granja, from the Biosciences, Languages, and Exact Sciences Institute (IBILCE) at UNESP, São José do Rio Preto campus, states that subjects addressed by the writer in the chronicles he published in periodicals were later recreated in his fictional works. As a result of her associate professorship thesis, last year Granja published Machado de Assis – Antes do livro, o jornal: Suporte, mídia e ficção (Machado de Assis – Before the novel, the newspaper: Support, media and fiction), in which she analyzes the dialogue between the texts Assis published in periodicals and his fiction writing. “The revaluation of genres that have been drowned out by novels reveals unknown aspects of his writing career. Five of his nine novels were published in sequence in periodicals before being published as books; same for nearly all of his short stories, which number about 200,” she points out.

Personal archives / Hélio Guimarães

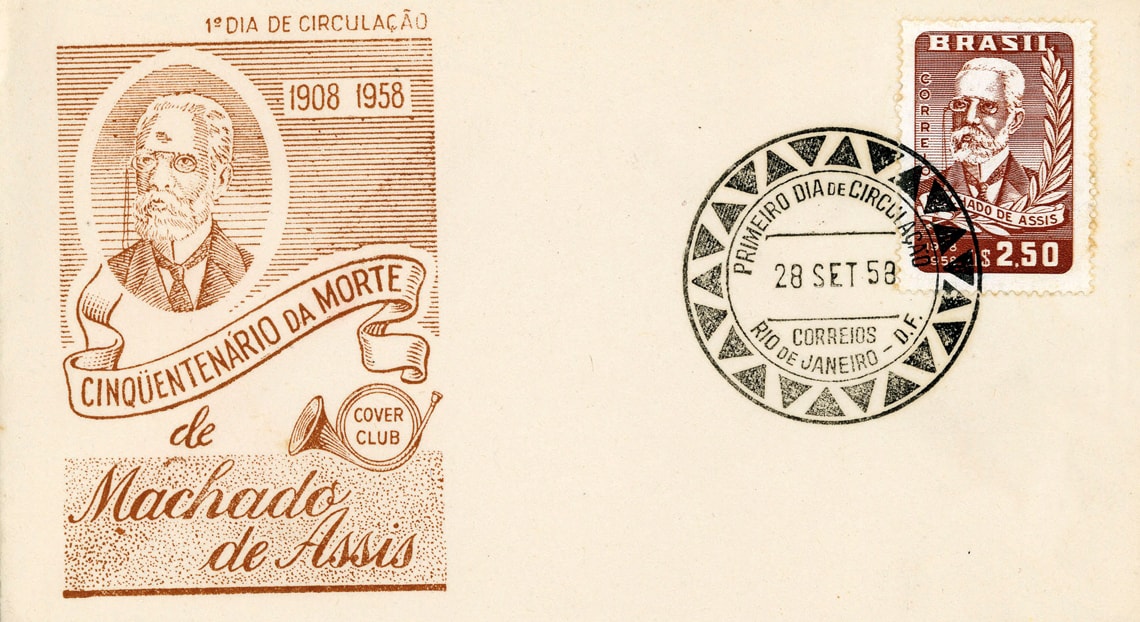

Os Correios (Brazilian Post Office) released a stamp in memory of the writer in 1958Personal archives / Hélio GuimarãesOfficial acclaim

His shift from a displaced writer in Brazil’s literary scene to a central author in modern history had its turning point in 1939, when then-President Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954) decreed celebrations to mark the one hundredth anniversary of Assis’s birth through events involving the National Library, the National Book Institute, and the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Service. The initiatives involved publishing commemorative editions of his novels, organizing an exhibition, and even issuing coins and stamps. “It was the first major case of literary acclaim in Brazil mobilizing a large official and editorial apparatus. Assis was taken by the Estado Novo [1937–1945] as an exemplary man and author, who fostered the development of a narrative centered on the trajectory of a poor boy born in Morro do Livramento who ascended to the Brazilian Academy of Languages,” explains Hélio Guimarães. Around the same time, critics such as Augusto Meyer (1902–1970) and Lúcia Miguel Pereira (1901–1959) began to fit him into the national and international literary tradition, a movement that became consolidated in the 1950s, when Antonio Candido (1918–2017) published Formação da literatura brasileira (The formation of Brazilian literature; Livraria Martins Editora, 1959).

The USP researcher also notes that, in the 30 years following the novelist’s death, the reality of his blackness was suppressed. “In a letter to José Veríssimo, Joaquim Nabuco [1849–1910] says he sees only the Greek in Assis,” he claims, noting that in his death certificate the novelist is classified as “white”. This situation began to change after a biography written by Lúcia Miguel Pereira in the 1930s framed Assis’s blackness positively and as the reason for his ability to see Brazilian society from different angles. “Today, Assis is claimed and presented as a black author—which illustrates how current discussions in the country continue to apply to him from the biographical perspective.”

Still as a result of his research, in a book to be published later this year, Guimarães will address Assis’s process of gaining acclaim after 1939, a period in which the internationalization of his work gained momentum, with the first versions of his novels being translated into English. In the wake of this process, Helen Caldwell (1904–1987), a professor at the University of California, translated Dom Casmurro in 1953 and produced a critical study on the 1899 novel. “Caldwell challenged the narrator’s authority and questioned his version of the marriage of Capitu, one of the characters, thus changing how the novel was traditionally read,” explains Guimarães. He stresses that this view had an impact on how Brazilian critics interpreted the novel; since the 1970s, they have argued that Assis’s novels contain criticism of how Brazilian society was formed. Today, Guimarães states, 180 years after his birth, these readings are central to understanding the author.

Project

Translators, translations, and editions of Machado de Assis’s work in English – Helen Caldwell and the University of California Press (nº 19/00643-5); Grant Mechanism Grant for Research Abroad; Principal Investigator Hélio de Seixas Guimarães (USP); Research Site University of California at Santa Barbara; Investment R$18,924.42.

Books

GUIMARÃES, H. S. and LEBENSZTAYN, I. (ed.). Escritor por escritor, Machado de Assis segundo seus pares 1908–1939. São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial, 2019.

AZEVEDO, S. M. Machado de Assis – Badaladas Dr. Semana. São Paulo: Nankin Editorial, 2019.

GRANJA, L. Machado de Assis – Antes do livro, o jornal: suporte, mídia e ficção. São Paulo: Editora Unesp Digital, 2018.