Léo Ramos Chaves

Physical and chemical treatments alter the properties of foods and make them last longerLéo Ramos ChavesIn recent years controversy has swirled around industrialized foods, especially those rich in sugars, fats, salt, and chemical compounds that increase durability or provide more aroma, color, and flavor. On the one hand, some groups of nutritionists and public health experts blame these foods for a growing risk of developing obesity and diabetes which is starting to be quantified; these two health problems are increasingly common around the world. Consumption of these foods, which were classified as ultra-processed in 2009 by epidemiologist Carlos Augusto Monteiro, a professor at the University of São Paulo School of Public Health (FSP-USP), is high in many rich countries where the proportion of individuals weighing more than considered healthy is also elevated, and is growing rapidly in countries with medium- and low-income populations. On the other hand, researchers in the area of food science and technology consider this classification imprecise. They also claim that consumption of this type of food, which allows part of the world’s population to have access to the minimum of calories required for survival, is only one of many factors to be considered in explaining these problems.

Recent studies have fed this debate by presenting initial evidence that greater consumption of this type of industrialized food can have a harmful impact on health. In February of this year, the British Medical Journal presented the results of a survey conducted in France, which for the first time suggested an association between increased consumption of ultra-processed foods and increased cancer risk. The French study was based on evaluation of data from 104,980 people aged 18 to 72 years who were part of the NutriNet-Santé project. The researchers separated the volunteers, who all were cancer-free at the beginning of the study, into four groups that only differed in relation to consumption of ultra-processed foods. Industrialized and ready-to-eat products accounted for 8.5% of the calories ingested each day among participants that consumed the least of these foods, and 32.3% of the caloric intake of the group that consumed the most; these foods were generally sweets, sweetened beverages, and breakfast cereal.

Over five years of follow-up, a small proportion of each group developed cancer. After ruling out protective effects against tumor risk (being younger or physically active) and aggravating factors (smoking or family history of cancer, among others), the researchers found that increasing the share of ultra-processed foods in the diet by 10 percentage points increased the chance of developing cancer by 12%.

The authors avoid stating that ultra-processed foods cause cancer. One reason is because it is not yet clear what in the composition of these foods could cause tumors to develop. “In addition to higher levels of salt, sugar, and fat, ultra-processed foods contain additives and compounds that are formed during industrial processing and may have an impact on health,” explains epidemiologist Chantal Julia, a researcher at Paris 13 University and one of the authors of the study.

“Ultra-processed foods are a recent invention of industry, which uses cheap ingredients to reduce the quantity of natural foods and decrease the price of products,” said Monteiro, who is a medical epidemiologist specializing in nutrition and participated in the Paris study. “Ultra-processed foods often contain little or nothing of the foods used to produce them.” In 2009, Monteiro proposed reclassifying food based on the degree of processing rather than macronutrients (protein, carbohydrates and fats). He expects that this way of looking at foods, known as the NOVA classification, will help provide a better explanation of the increase in health problems associated with nutritional imbalances. This is the case with obesity, which doubled in 70 countries between 1980 and 2015 and today affects 604 million adults and 108 million children worldwide.

Besides the French research, few studies have been able to establish a direct connection between health problems and consumption of ultra-processed foods. Previously, other studies had already identified a connection between consumption of soft drinks and sweetened beverages or sugar-rich foods and greater risk of developing metabolic and cardiovascular problems. But none grouped these foods into the same category, which according to some nutritionists would eliminate distortions. “This classification allows food attributes beyond nutritional composition to be seen, such as hyperpalatability, which leads people to eat beyond the point of satiation,” says Inês Rugani Ribeiro de Castro, a professor in the Department of Nutrition at Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ) and member of the Brazilian Association of Collective Health (ABRASCO).

Before the article in the British Medical Journal, the nutritionist Raquel Mendonça (who is currently completing a post-doctoral internship at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, UFMG), had already published two other studies linking increased consumption of ultra-processed foods to health problems. During her doctorate, part of which was completed in Spain, Mendonça worked with the team of epidemiologist Miguel Ángel Martínez-González, a professor at the University of Navarra and the Harvard School of Public Health in the United States. Martínez-González coordinates a study monitoring the health of 22,500 young adults which investigates the causes of obesity and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.

In one project, Mendonça examined the dietary patterns of 8,451 participants aged 27 to 49 years and at a weight considered healthy at the start of the study, with body mass index (BMI) ranging from 18.5 to 25. The volunteers were separated into four groups according to the number of servings of ultra-processed foods they consumed. Those who ate the least of this kind of food ate an average of a portion and a half per day, the equivalent of a small piece of a hamburger. At the other extreme, people consumed six servings: generally processed meats and sausage, cookies, chocolate, donuts and other sweets, as well as soft drinks and sweetened beverages. This group ate 40% more calories and 6% more fat, but 10% less protein and 18% less dietary fiber.

Nine years after the study began, a significant part of each group was overweight (BMI 25–30) or obese (BMI over 30). Even after discounting the additional consumption of calories and other factors associated with obesity, the group that consumed more ultra-processed foods had a 26% higher risk of weighing more than healthy levels than the group that least ate this type of food, according to an article published in 2016 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. In a third study, Mendonça observed that consuming more ultra-processed foods increases the probability of developing high blood pressure, a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases associated with 10.4 million deaths per year worldwide.

Nine years after the study began, a significant part of each group was overweight (BMI 25–30) or obese (BMI over 30). Even after discounting the additional consumption of calories and other factors associated with obesity, the group that consumed more ultra-processed foods had a 26% higher risk of weighing more than healthy levels than the group that least ate this type of food, according to an article published in 2016 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. In a third study, Mendonça observed that consuming more ultra-processed foods increases the probability of developing high blood pressure, a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases associated with 10.4 million deaths per year worldwide.

Now these studies provide the most robust evidence of potential harmful effects ultra-processed foods may have on health. “They are, in fact, the only real tests of the hypothesis that ultra-processed foods could cause disease,” says Barry Popkin, professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. An economist by training, Popkin specializes in epidemiology and nutrition and for almost 40 years has studied the influence of changes in the pattern of nutrition and physical activity on obesity and other health problems in a number of countries, including Brazil. In his opinion, we still cannot say how ultra-processed foods contribute to obesity.

What is missing? More studies like these, which can establish whether there is a cause and effect relationship between consumption of these foods and obesity. “The three studies are small, given the complexity of the question they attempt to answer,” says physician Lício Velloso, a professor of the School of Medical Sciences at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and coordinator of the Obesity and Comorbidities Research Center, one of the Research, Innovation and Dissemination Centers (RIDC) funded by FAPESP. Velloso, who investigates the biochemical mechanisms of obesity and diabetes, says, “We need to conduct studies with a larger number of people who have varied genetic composition.”

Demonstrating a causal relationship is not simple. And it is more difficult in the case of obesity, a problem that may have genetic and environmental causes. One of the requirements for identifying causality is showing that the alleged cause regularly precedes the studied phenomenon. This is possible in longitudinal or monitoring studies, such as those conducted in Spain and France. In this model, researchers follow a population which initially does not have the problem, and periodically record changes that occur after an intervention or exposure to a risk factor. However, most studies that attempt to associate the consumption of ultra-processed foods with health problems are cross-sectional studies. In this type of research, researchers collect data on outcome and exposure at the same time, making it more difficult to confirm that the results stem from exposure to the phenomenon.

Since they proposed the NOVA food classification, Monteiro and his team found that the share of ultra-processed foods in the Brazilian diet has grown 22% over the last decade (see table) and that these foods are more available in the homes of individuals who are overweight or obese. They also found that those who consume more of these foods (more than 35% of their daily calories) ingest high levels of free sugars and low levels of fiber, which reduces satiety.

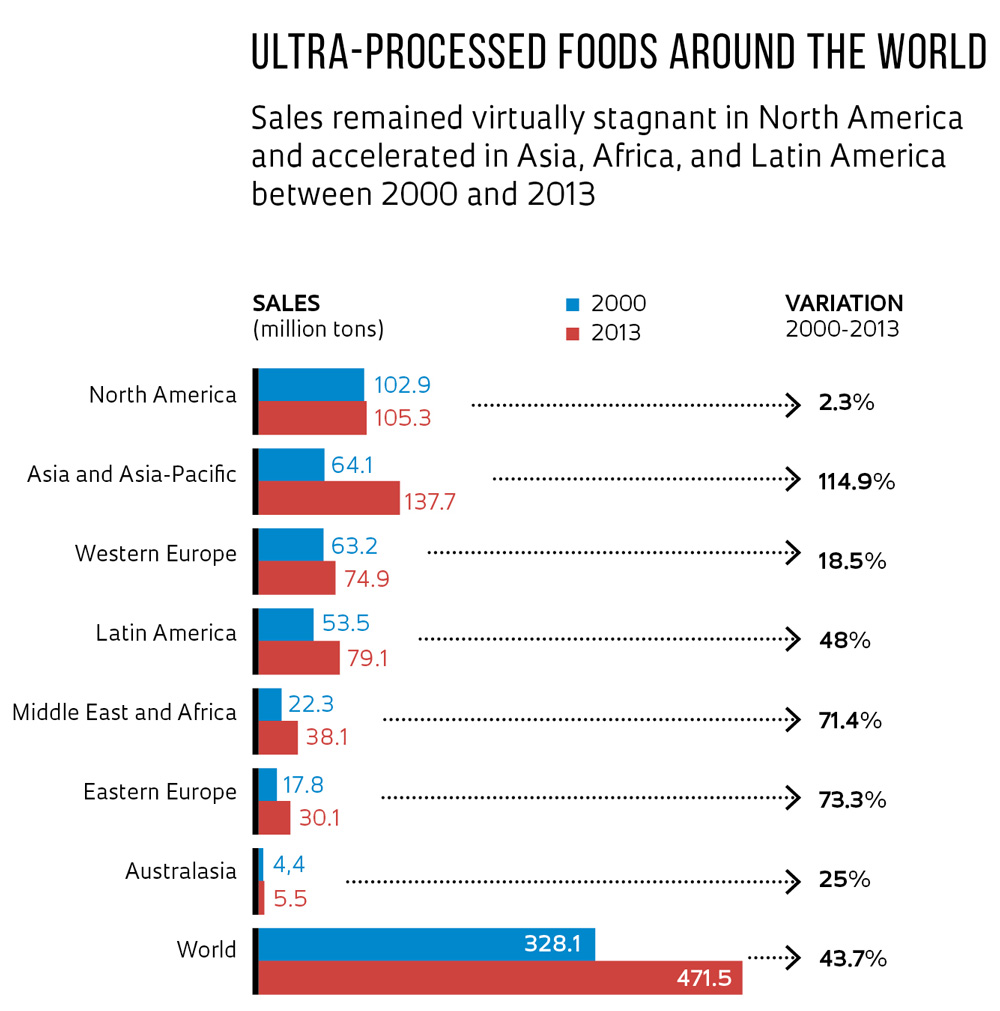

The consumption of ultra-processed foods has historically been high in rich countries like the United States, Canada, and England, where they account for more than half of daily calorie intake. But sales in these nations seem to have reached the saturation point and stagnated over the last decade, according to an analysis of sales in 79 countries between 1998 and 2012 conducted by Popkin, Monteiro, and Jean-Claude Moubarac of Canada. Their study, published in 2013 in the Obesity Review, identified advancement by transnational industry in producing and distributing these foods in countries with middle- and low-income populations. During this period sales increased an average of 2.8% per year in Peru, Mexico, Brazil, and Turkey, and 5.5% per year in China, India, and Indonesia, among other countries. “This industry is the force that now shapes the global food system,” the researchers wrote.

Over the last two decades the belief has been growing among researchers, medical entities, and consumer protection agencies that foods rich in salt, fat, sugar, and artificial compounds (which Monteiro grouped under the term ultra-processed foods) have a harmful side. In 2012, the journal Plos Medicine published a series of articles titled “Big Food” which evaluated the impact of the global food industry on health. In one article, economist and sociologist David Stuckler of the University of Cambridge in England and nutritionist Marion Nestle of New York University reminded readers that the world market for food and beverages is concentrated in the hands of a few multinationals. At that time, the 10 largest companies (which they dubbed Big Food) were responsible for half of sales in the United States and 15% in the rest of the world. According to Stuckler and Nestle, there was evidence that these companies used strategies similar to the tobacco industry to evade regulations and taxes. “Growth in the consumption of Big Food products closely corresponds to rising levels of obesity and diabetes,” they said.

In general, these foods are formulated to be appetizing, cheap, and have long shelf lives, and can be transported long distances. “Industrialized food is what allows a good portion of people in the world to eat,” underscores biochemist Bernadette Dora Gombossy de Melo Franco, professor in the Department of Food and Nutrition at the USP School of Pharmaceutical Sciences (FCF-USP) and coordinator of the Center for Food Research (FORC), another RIDC supported by FAPESP. “Some decades ago, food could not be shipped to far-off regions in countries like Brazil because it was highly perishable,” says Eduardo Purgatto, professor at FCF-USP and a member of FORC. “Processing changed this scenario.”

For Velloso at UNICAMP, the role of industry needs to be understood in two ways. “On the one hand, it allows part of the population in regions of the planet that depend on local production, which can fluctuate greatly, to have a certain guaranteed access to food; on the other hand, excessive consumption of these foods, as is the case in the poorer population in urban centers, can affect health.”

Although Monteiro demonstrates to what degree ultra-processed foods contribute to obesity, it is almost certain that these foods alone do not explain everything. A few genes are known that, if altered, can cause a person to get fat, but there are more than 300 which govern the accumulation and consumption of energy. This biological complexity was expanded in recent decades by the growth of the global food supply and changes in cooking. As industrialized foods became more available and edible vegetable oils grew cheaper, average calorie intake rose from 2,400 kilocalories per person per day in 1970 to 3000 in 2015, according to data from the United Nations Fund for Food and Agriculture (FAO). There was also a reduction in physical activity and changes in the way food is prepared. “Half of Chinese are overweight because they no longer bake or steam foods, but started frying them,” says Popkin. “In other countries, people gained weight from eating a lot of bread, tortillas, and fried foods, not ultra-processed foods.” Bernadette Franco agrees: “Placing the blame on a single cause, without considering the reduction in physical activity and the way people cook, in the case of Brazil adding too much salt and sugar, explains a small part of the problem.”

The proposal to place ultra-processed foods into a separate category that brings together what is unhealthy in food has generated a polarized debate. Those who disagree see no foundation for this idea. Franco believes there is no clear definition of what ultra-processed foods are. Michael Gibney of University College Dublin says that it would be necessary to establish limits for salt, sugar, fat, and additives to define these foods. Gibney is a member of the Nestlé scientific commission and published a 2017 review in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition which stated evidence that ultra-processed foods are nearly addictive is still lacking.

In other comments published in 2017 in the journal EC Nutrition, food engineer Raul Amaral Rego and biologist Airton Vialta, researchers from the Food Technology Institute (ITAL), which is linked to the São Paulo State Secretary of Agriculture and Supply and the São Paulo Agribusiness Technology Agency, say that Monteiro’s system is fragile and conflicts with well-established classifications. “There is no sense in trying to classify food based on the degree of processing, since the same food can be processed in different ways depending on the product that you want to achieve,” they wrote. Rego and Vialta had no comment for this article.

For a decade, Brazil has tried to regulate advertising of foods and beverages that contain high levels of sugar, salt, and fat

Meanwhile, supporters of the new classification state that it can help guide measures that benefit the health of the population. “By bringing together a diverse group of foods in the ultra-processed category, a summary indicator is created, which permits better understanding of the quality of people’s diets,” says Inês Rugani Ribeiro de Castro of UERJ.

Based on the new classification, in 2014 the Ministry of Health produced the Dietary Guide for the Brazilian Population. This document was distributed to 60,000 healthcare professionals and educators, and recommends greater consumption of foods in their natural state, reduced intake of processed foods, and avoiding ultra-processed foods. Even though the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency (ANVISA), the federal agency that controls registration of medications and food, does not use the term ultra-processed, for more than a decade it has tried to regulate advertising for food and beverages rich in sugar, salt, fat, and calories which targets children and prohibit sales in schools, which is already the practice in cities in some states. It is an effort to combat growing rates of overweight and obesity in the country; today 15% of children and 58% of adults are above healthy weights. After discussing stringent controls with society and industry for four years, in 2010 ANVISA published a mild resolution which was suspended after by lawsuits from the advertising and food sectors.

When the rate of overweight people in Chile reached an alarming 75%, the country took decisive measures in November 2017 to ban commercials for foods with high levels of calories, salt, sugar, and fats on free and cable TV from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. A 2016 law forced the industry to change product packaging, removing iconic characters like the tiger that used to appear on sugary breakfast cereals and displaying alerts on the levels of ingredients considered unhealthy, a measure currently under discussion in Brazil.

In addition to restrictions on advertising and changes in labeling, Popkin, Monteiro, and other specialists advocate increasing taxes on these foods. “Removing ultra-processed foods from the diet is the first step in promoting healthy eating habits,” says Popkin.

Purgatto of FORC proposes another way: for sectors of government and society to work with the food industry. “Only industry,” he says, “will be able to produce better-quality processed and ultra-processed foods, maybe with more fiber and protein, and make the prices affordable for most of the population.”

Project

Consumption of ultra-processed foods, nutritional profile of diet and obesity in seven countries (No. 15/14900-9); Modality Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Carlos Augusto Monteiro (USP); Investment R$1,506,407.84.

Scientific articles

FIOLET, T. et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. British Medical Journal. Feb. 14, 2018.

MENDONÇA, R. D. et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: The University of Navarra follow-up (SUN) cohort study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. Vol. 104, no. 5, pp. 1433–40. Nov. 2016.

MENDONÇA, R. D. et al. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of hypertension in a Mediterranean cohort: The seguimiento Universidad de Navarra project. American Journal of Hypertension. Vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 358–66. Apr. 1, 2017.