Isabella Matheus / Pinacoteca Collection in the State of São Paulo

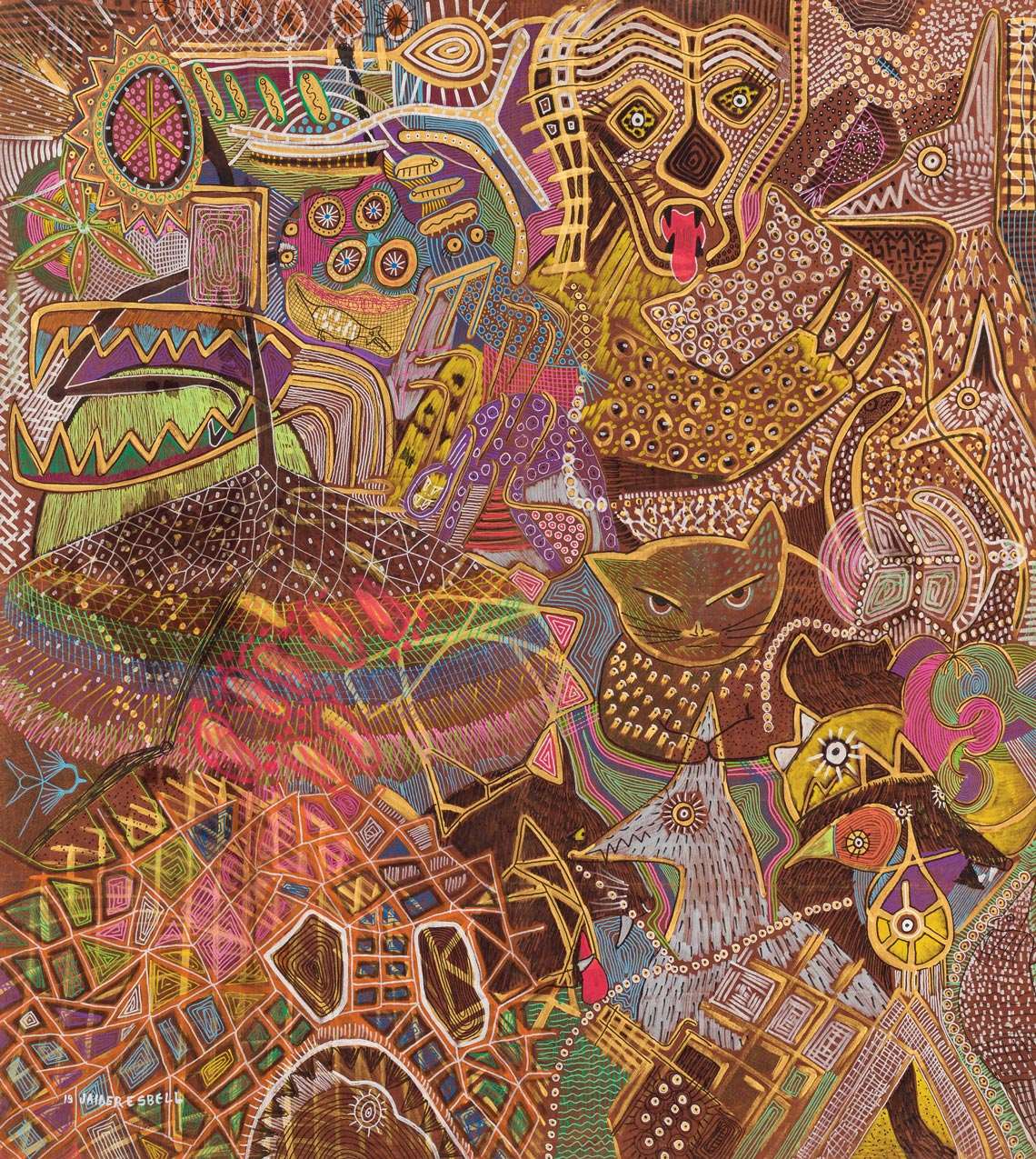

Feitiço para salvar a raposa Serra do Sol (Magic spell to save the fox Serra do Sol), a painting by Jaider Esbell, included in the Pinacoteca collection in 2019Isabella Matheus / Pinacoteca Collection in the State of São PauloThe increase in indigenous participation in academia, the dialogue between contemporary artists and social science methods, and the review of the artistic canon proposed by historians have fostered the inclusion of works produced by native populations in art museums, increasing their presence beyond ethnographic and archaeological collections. The movement has been growing in countries such as Australia and Canada since the end of the twentieth century and, in Brazil, it has begun to gain strength in the last five years. Institutions, such as Pinacoteca and the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP), both in the capital of São Paulo State, are investing in the acquisition of indigenous artwork, organizing exhibitions, and contracting indigenous curators with the goal of rethinking their collections.

With indigenous prominence as one of their primary tracks, the phenomenon was also motivated by academic discussions, with studies by the German Hans Belting as one of the theoretical marks of this process. “According to Belting, the history of art must open itself to creating different traditions and breaking ethnocentric classifications,” observes anthropologist Ilana Seltzer Goldstein, from the School of Philosophy, Languages and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo (EFLCH-UNIFESP). With a similar analysis, art historian Claudia de Mattos Avolese, from the Art Institute (IA) and postgraduate program in history at the Institute of Philosophy and Human Sciences at the University of Campinas (IFCH-UNICAMP), recalls that when the field of art history began to develop in the nineteenth century, the concept of beautiful was still a determining factor in the definition of an artistic object. “Furthermore, a hierarchy was established for esthetic genres, in which certain mediums, such as oil paintings, were more valued than others. With this in place, a convention was developed that was incapable of including, for example, items produced in indigenous ritual contexts,” she explains. According to Avolese, the education her generation received about the field of art history was limited to a western European tradition. Indigenous or African expressions were considered objects of anthropological analysis.

In recent years, indigenous works have begun to be integrated into permanent collections in institutions such as the São Paulo Museum of Art

Fernanda Pitta, curator of the Pinacoteca in the State of São Paulo, observes that the most circulated manuals in undergraduate courses, among them the books of Walter Zanini, José Roberto Teixeira Leite and Pietro Maria Bardi (1900–1999), begin to tell the history of art in Brazil beginning with the works of native populations. “Despite being recognized as part of national artistic history, indigenous art has been considered an artifact, present in archaeological and ethnographic institutions. Art museums have not included these works in their collections, which does not align with the importance of its production, including recent works,” adds Pitta, also a professor at the Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP).

With a plan to expand this field of thought, Avolese founded five years ago a new line of research in UNICAMP’s postgraduate program, called “Issues of non-European art, centered on Japanese-Brazilian, Amerindian, and African cultures.” The field of art history is opening up and getting closer to other forms of cultural production. In this respect, one of the ways of avoiding Eurocentrism within the discipline was to learn using anthropology methods,” she shares. Similarly, Goldstein says that, since it was founded in 2009, UNIFESP’s undergraduate program in art history includes in its range of required disciplines Amerindian, Islamic, Asiatic, and African art, which are offered alongside other traditional disciplines, such as the Renaissance and Baroque art. In her classes on Amerindian art, Goldstein uses anthropological literature as a way to learn more about the meaning of certain types of artistic expression. “As we read ethnographic passages of different peoples, we learn, for example, that body painting can both communicate something about the identity of the person who is painted and facilitate connections with supernatural beings and other levels of the cosmos,” she says.

Isabella Matheus / Pinacoteca Collection in the State of São Paulo

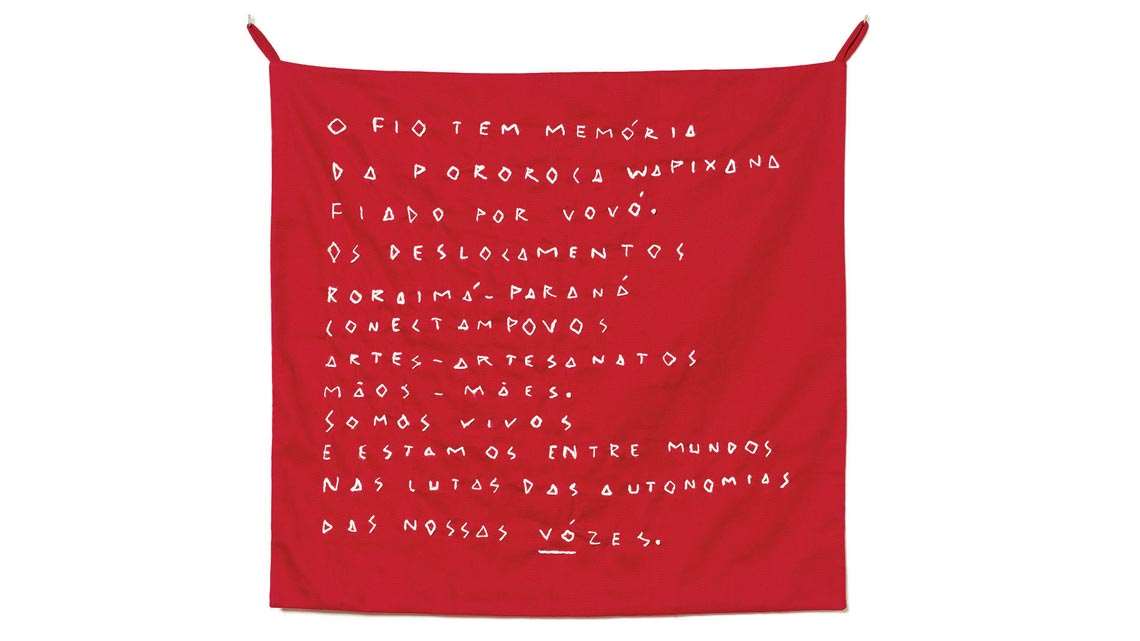

Pororoca Wapichana, produced by Gustavo Caboco and Lucilene WapichanaIsabella Matheus / Pinacoteca Collection in the State of São PauloJochen Volz, executive director of the Pinacoteca, notes that this process of growth has revealed the limits of the categories critics use to assign value to the works, among them the concepts of cultured, naive, popular, folkloric, or craft art. Established in 1905, together with the Arts and Trades High School, the Pinacoteca, from the beginning, has adopted as a parameter the techniques and criteria of European art, which, as Volz points out, defined the way the country thought about art during most of the twentieth century. “However, the labels we were used to using were put into question at a time when we also began to ask ourselves which version of art history we wanted to share in the institution,” she reports. Volz believes that these thoughts reverberate in debates that take place around the world, particularly in Canada, the United States, and Australia.

In her doctoral thesis defended in 2012 at UNICAMP, during a sandwich period at the Australian National University in Camberra, Australia, Goldstein studied the insertion of Brazilian aboriginal art in the art system. “The Australian case is unique to the extent that, until the mid-1970s, the aboriginal peoples were seen as the most ‘primitive’ populations on the planet, and today their works circulate in biennials, such as that of Venice, and are bought by institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) in New York,” she recounts. According to the researcher, the majority of art museums in Australia have indigenous pieces in their collections. Goldstein explains that this reality was created with the support of government policies that have been under development for close to four decades and include awards, funding for the creation of cooperatives, management courses, and requirements for indigenous curators in Brazilian museums that have indigenous collections.

Isabella Matheus / Pinacoteca Collection in the State of São Paulo

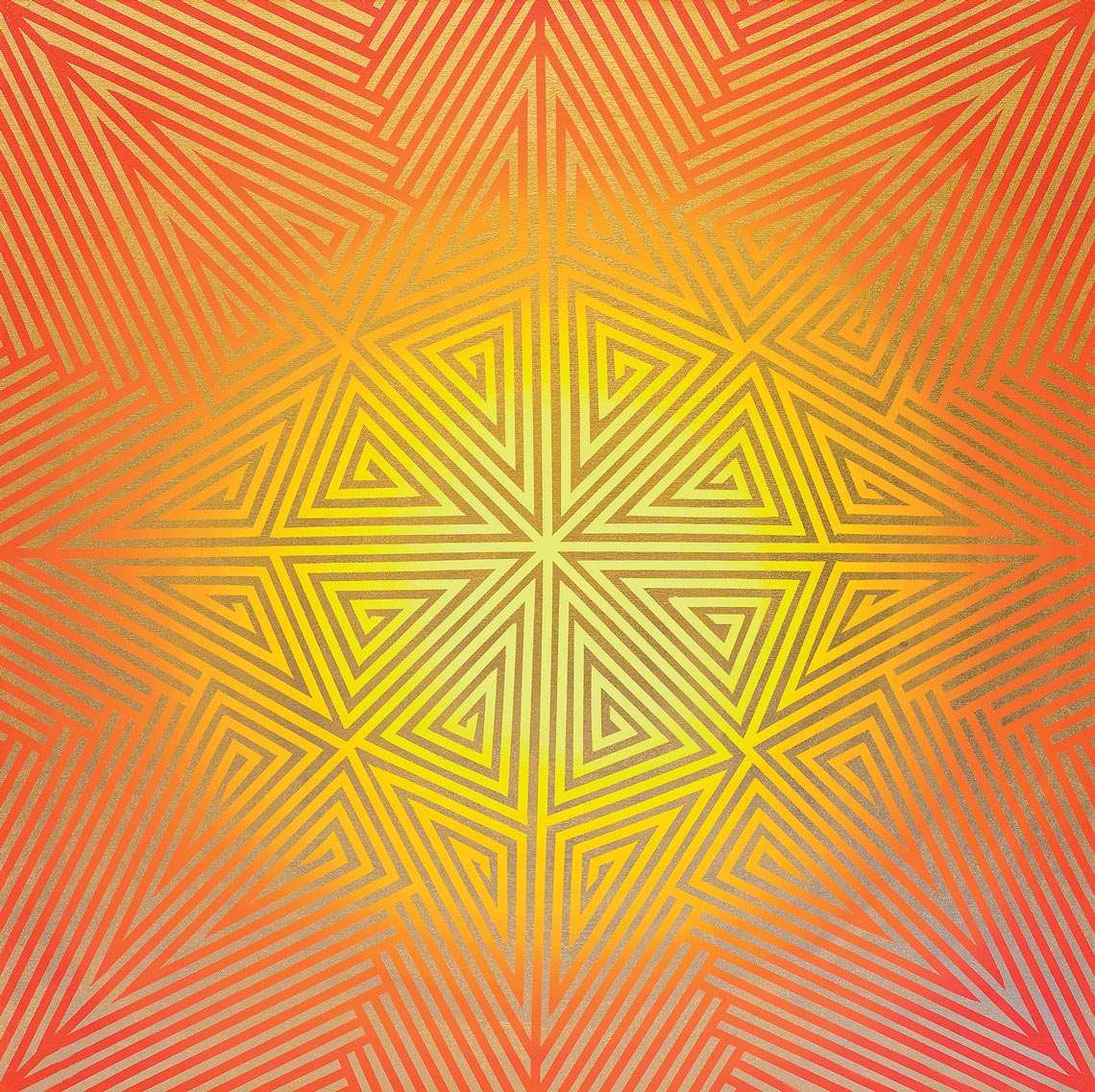

Muhipú Saãrô (sunset), by Daiara TukanoIsabella Matheus / Pinacoteca Collection in the State of São PauloIndigenous art has also acquired new spaces in institutions throughout Brazil. The movement has primarily been the result of the voices of the native peoples, who began to see it as an opportunity to call attention to specific demands, such as the right to mark territory and the strengthening of identity issues. “The visibility that the indigenous artists have achieved in recent years is the result of a confluence of historical factors that begin with the guarantee of rights—established by the Constitution of 1988—that include intense film, literary, musical, and content production in social media, and an increasing presence in postgraduate programs,” highlights Jamille Pinheiro Dias, researcher for the project “Cultures of anti-racism in Latin America,” at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom.

With an undergraduate degree in philosophy and a PhD in education from the University of São Paulo (USP), Daniel Munduruku observes that, in the last 10 years, there has been a change in the appreciation of indigenous art, motivated initially by film production of different groups, followed by the emergence of writers. “This movement has favored the broadening of what visual arts is in Brazil,” adds Munduruku. Dias highlights that indigenous production has always existed throughout the history of Brazil. The difference today is that this production has gained visibility. “Artists, such as Denilson Baniwa and Daiara Tukano, make it clear that art is not separate from the fight of the indigenous movement. On the contrary, it represents its growth,” maintains the researcher.

Masp / São Paulo Museum of Art Assis Chateaubriand Collection

Dami (Paulista Avenue) is a painting by the group Ibã Huni Kuin and Mana Huni Kuin donated to MASP in 2020Masp / São Paulo Museum of Art Assis Chateaubriand CollectionGoldstein recalls that the modern European groundbreakers of the first two decades of the twentieth century had already drawn closer to the culture of non-western populations, particularly from Africa and Oceania. She is currently locating the existence of the first wave of interest using expressive forms of native populations. “Artists of these movements used themes of these peoples, not to get to know them better, but to critique their way of life and the system of western art,” informs the anthropologist. Thus, she recalls that scholars of Cubism claim that the creation of the painting Les demoiselles d’Avignon, by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), was inspired by African masks that created geometric, stylized faces.

Edouard Fraipont / Courtesy of the Artist and Luisa Strina Gallery

Zero real, by Cildo MeirelesEdouard Fraipont / Courtesy of the Artist and Luisa Strina GalleryIn Goldstein’s opinion, at the end of the last century, there was a second wave of interest among indigenous peoples in the artistic world. “Contemporary artists began to use methods of anthropology and sociology, such as ethnographic research or the application of surveys, and also to discuss issues of identity and representation, at a time that was characterized by some authors as an anthropological turning point in contemporary art,” she outlines. In this same vein, she mentions North American artist Claire Pentecost, professor at the Department of Photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which, in 1990, developed an exhibition based on the history of Ishi (?–1916), the last representative of a population that disappeared in California. Pentecost did a survey with indigenous people to obtain memories about his character, creating the artwork from the responses she received. Besides Pentecost, in 2007, Uriel Orlov of Germany showed a video in a contemporary art center in Freiburg, Germany, with scenes of his meeting with the king of Benin in Africa 10 years earlier. At the time, they talked about bronze pieces that had been accumulated in the country by the British in the nineteenth century and which, today, are spread throughout European museums. “This movement also exists in Brazil, where nonindigenous artists and curators have sought to draw closer to native populations,” comments Goldstein, as she talks about the curation of Moacir dos Anjos in A queda do céu (The falling sky), an exhibition organized in the Palace of Art in São Paulo at the beginning of 2015 that was based on the book of the same name published by Davi Kopenawa and anthropologist Bruce Albert; the work of Bené Fonteles in the 2016 Biennial of São Paulo, which involved the construction of a hut in the exposition pavilion; or even the Zero real note, by Cildo Meireles, stamped with the figure of an indigenous person. “Contemplating the Amerindian universe, initiatives such as these increased sensitivity for the work of indigenous artists in institutional spaces that had been exclusively dominated by western art,” she observes. As part of this process, indigenous artists began to exhibit in university museums, such as the exhibit Mira – Artes visuais contemporâneas dos povos indígenas (Contemporary visual arts by indigenous peoples), held in 2014 in the Knowledge Space at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and Reantropofagia, organized at the Center of Art at the Fluminense Federal University (UFF), in 2019, with curation by Denilson Baniwa.

As this process continues, in October the Pinacoteca of São Paulo inaugurated its first exhibition dedicated to the art of native populations in Brazil. The exhibit named Véxoa: Nós sabemos (Véxoa: We know) was curated by an indigenous member and is the responsibility of education PhD Naine Terena. It brings together paintings, sculptures, objects, videos, photographs, and performances by 23 artists or groups from different regions throughout the country. Pitta, of the Pinacoteca, explains that the initiative began through initial discussions in 2017 with the purpose of updating the institution’s collection and seeking strategies to incorporate indigenous art in its collections. In that year, she was invited by The Clark Art Institute, a center of art history research in the United States, to lead a group of studies about theoretical and methodological questions with a view to re-establishing the exhibit at the Pinacoteca over the long term.

Levi Fanan

Views of the exhibition Véxoa – Nós sabemos, in São Paulo. The show includes both works by contemporary artists, such as Denilson BaniwaLevi FananIn 2018, through the support of a visiting researcher provided by FAPESP to Christopher Heuer, of Rochester University and one of the directors of The Clark Art Institute, both in the United States, and as part of a project coordinated by Avolese, Pitta and Valéria Piccoli, also curator of the Pinacoteca, a study group was formed in Brazil, with the participation of postgraduate students at UNICAMP, UNIFESP, and USP. “At the time, we discussed the relationships between, art, ethnography, and visual culture as a path to build a new exhibition in the permanent collection of the Pinacoteca,” adds Pitta. Inaugurated in October 2020, a new presentation of the institution’s permanent collection of Brazilian art substituted the previous linear and chronological narrative with a thematic one. Some of these themes, such as territory or body, seem to be influenced by indigenous thinking, in Goldstein’s view.

In 2018, the Pinacoteca organized an international workshop to bring together thinkers involved in the redesign of museums. “Among the invitees was Naine Terena, whose speech encouraged the institution to think about which space could be made available for indigenous artists,” recalls Pitta, citing her work to articulate the actions of international peoples and her collaboration with the Biennial of São Paulo in 2016. The institution then invited Terena to curate the exhibit inaugurated in October. “We brought together a number of diversified works to show how contemporary indigenous art involves traditional ceramics to audiovisual works,” informs the curator, who credits indigenous leadership in the process of gaining space in art museums. “Before curating indigenous art, I worked with contemporary art, with artists such as Gervane de Paula. In 2012, with support from the Petrobras Cultural RFP, I curated an exhibition of indigenous art in a small museum in the city of Aquidauana, in Mato Grosso. The way to break Eurocentrism in the arts has been through the uprising of native populations, in different periods of time,” she adds.

Levi Fanan

…and masks and clothing of the Wauja peopleLevi FananWith the goal of offering new perspectives about indigenous production, photographer Edgar Correa Kanaykõ exhibited in the Pinacoteca five works about the activities carried out in the Acampamento Terra Livre (Free Land Settlement) in Brasília. He reports that he began to do photography in the 2000s when his village in the North of Minas Gerais received electrical energy and acquired computers and cameras. “The village had an association that bought this equipment with a view to registering the projects developed by the Xakriabá people. Today, through photography, I am able to show how our identity is diverse, through my own eyes,” he says. Gustavo Caboco, another participant of the exhibit that is being showcased until March 22, highlights how indigenous production has been presented by the Pinacoteca. Unlike archaeological and ethnographic museums, where indigenous objects tend to be exhibited without distinction, as pieces that are collectively attributed to an ethnicity, at the Pinacoteca each work has its authorship identified. “Véxoa is the first large exhibition organized in a public art institution and that is proof of the significant changes taking place in museological spaces throughout the country,” recognizes Goldstein of UNIFESP. “The initiative is also a milestone because it is happening in the context of changing policies around the acquisition and construction of the Pinacoteca collection, which bought the works of Denilson Baniwa, Jaider Esbell, Daiara Tukano, Edgar Kanaykõ, Gustavo Caboco and the Mahku Group. This collective forecast represents not only a change in esthetic discussions, but also a conquest of political and economic power for native populations,” says Dias of the University of Manchester.

In an effort similar to that of the Pinacoteca, MASP integrated the first works of indigenous art into its permanent collection in 2019 through donations made by its own artists. In the same year, the institution contracted its first indigenous curator, Sandra Benites, a PhD student in social anthropology from the National Museum at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (MN-UFRJ). For 2023, the museum is planning to organize a showing about indigenous history, which will be curated by Benites.

Project

Comparativism beyond the West: New theories and methods to achieve an inclusive history of art (no. 17/23454-8); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant – Visiting Researcher; Principal Investigator Claudia Valladão de Mattos Avolese (UNICAMP); Visiting Researcher Christopher Heuer; Investment R$48,810.41.

Scientific article

GOLDSTEIN, I. S. Da “representação das sobras” à “reantropofagia”: Povos indigenous e arte contemporary no Brazil. MODOS. Revista de História da Arte. Campinas. Vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 68–96. Sept. 2019.