Bruno Meyer's personal collection

Meyer, 40, when he lived in FranceBruno Meyer's personal collectionThe man had three different first names, two nationalities, and not a single physics degree. Even without a formal undergraduate or graduate degree, João Alberto Meyer (1925–2010), better known as Jean Meyer, worked as a physicist at some of the world’s most prestigious research institutions. He was instrumental in the experimental development of particle physics in Europe, primarily within the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), in Geneva, Switzerland. He also spearheaded a groundbreaking project to study alternative energy sources at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the 1970s. For those who knew him, Meyer was a scientific and social bridge-builder, able to coalesce students and lead interdisciplinary projects like few others could.

João Alberto was born Hans Albert in the then city-state of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland), into an affluent Jewish family. In 1935, leaving behind parts of their cultural heritage, the Meyers fled mounting antisemitism and escaped to France. At one of the most traditional high schools in Paris, Hans became Jean. “It is a name that, to this day, family and many friends use to refer to him,” clarifies physicist Bruno Meyer, an energy consultant in France and one of his four children.

Faced with the imminent German invasion of France, in 1940, the Meyers fled once again, first to Madrid and then to São Paulo. With his family under financial strain, young Jean had to find work, despite his excellent performance at school and having reached high school equivalency at the Lycée Pasteur de São Paulo international school at the age of 16.

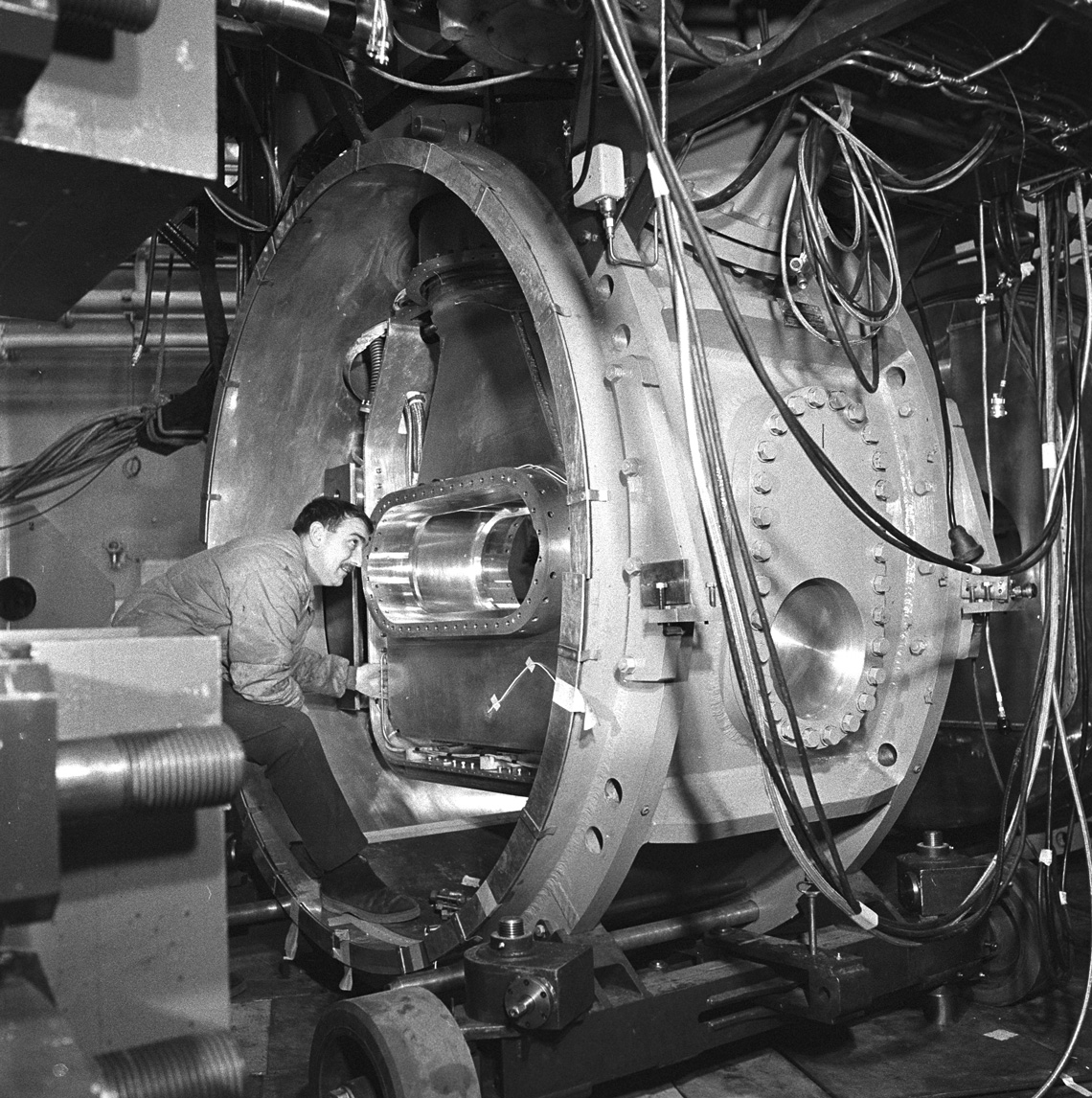

CERN

Bubble chamber built at the Saclay Nuclear Research Centre and used at CERN in the 1960sCERNAs a worker at the Orquima chemical company, he was a jack of all trades and even cleaned bathrooms, recounts his son. He eventually met the company’s scientific director, Pawel Krumholz (1909–1973), a Polish chemist with Brazilian citizenship who promoted him to laboratory technician. Meyer’s admiration for Krumholz motivated him to attend college. In the mid-1940s, he applied to the Chemistry program at the University of São Paulo (USP), but at the time French diplomas were not valid for college admissions. He was encouraged to speak with Italian-Ukrainian physicist Gleb Wataghin (1899–1986) at the nascent School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at USP, in 1934. Impressed with Meyer’s practical ability to handle laboratory equipment, Wataghin was convinced that the young man should become a physicist and promised to straighten out the diploma issue. “He never delivered, but this pretense was the mainspring to my involvement in physics,” explains Meyer in an interview for the History of Science in Brazil project, supported by the Getulio Vargas Foundation of Rio de Janeiro.

In São Paulo, in the early 1940s, modern physics was debated by professors and students with intense intellectual effervescence, with evening seminars on quantum mechanics and general relativity, hosted at the home of physicist Mário Schenberg (1914–1990) of Pernambuco (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 307). Schenberg would organize seminars and debates on the latest topics in modern physics, while writers, painters, and philosophers would engage in conversations about philosophy and the arts. “There were few students and many teachers,” in the words of Meyer. It was at these seminars that Meyer discovered particle physics, to which he would devote most of his career.

In the early 1950s, as a naturalized Brazilian citizen by the name of João Alberto, Meyer worked as a physics research assistant at USP. Newly married to professor and literary critic Marlyse Meyer (1924–2010), he returned to France in 1952 on a research grant. He spent a year at the Polytechnic Institute of Paris, where he learned about one of the most important developments at the time, the bubble chamber, which is a fundamental device for observing the properties of fragments resulting from collisions between subatomic particles. Back at USP, in the 1950s, he found himself in the unlikely situation of being both assistant and student at the same time—his lack of a diploma was also a pretext for paying him a salary he considered to be too low. In 1956, he went to Italy to research at the University of Padua. The modest pay was offset by the opportunity to build Europe’s first bubble chamber, invented in the United States years earlier.

Bruno Meyer's personal collection

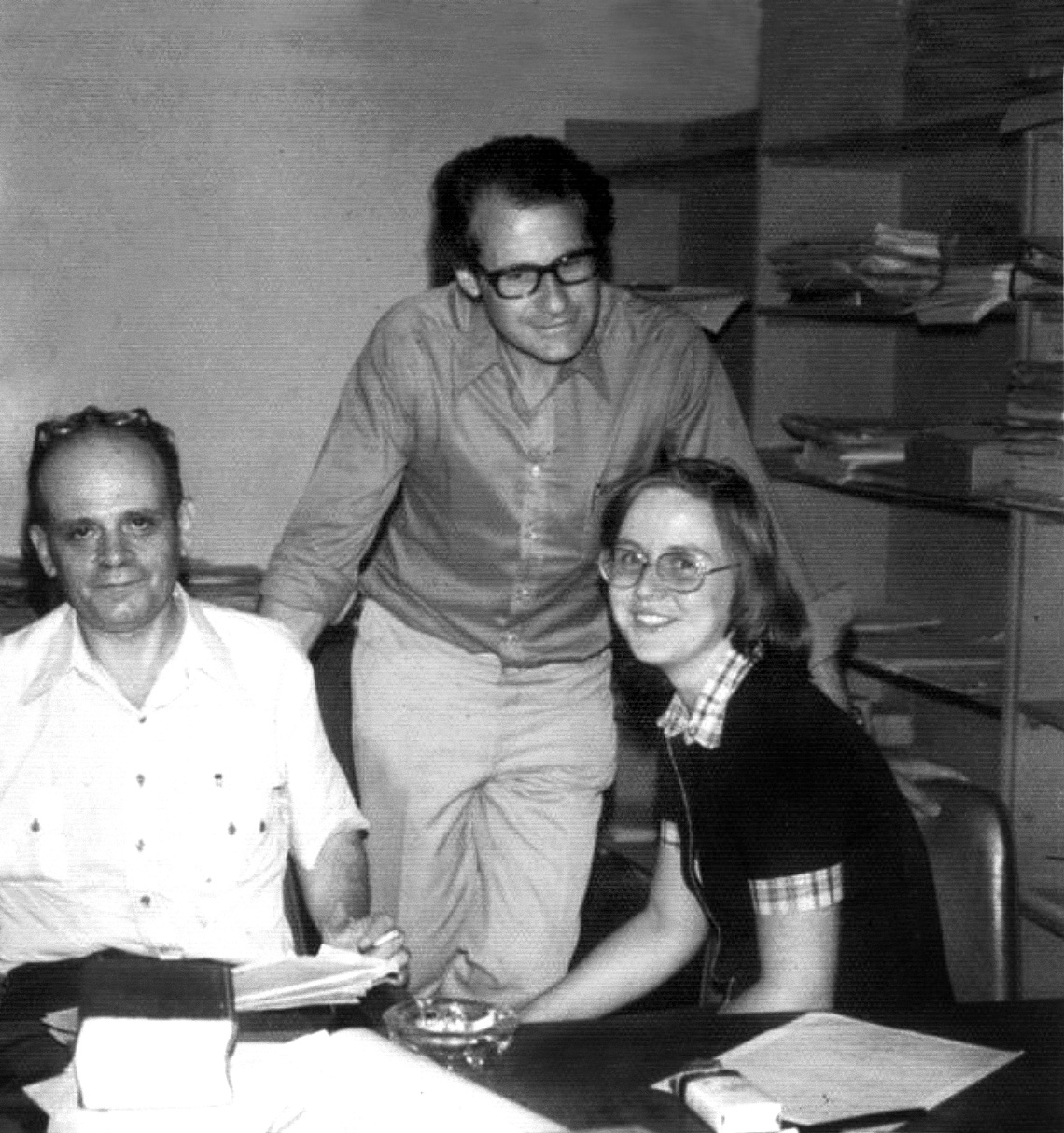

At UNICAMP, in 1975: Meyer (standing), creator of the Hydrogen Laboratory, flanked by César Lattes and Carola Dobrigkeit, both from the Institute of PhysicsBruno Meyer's personal collectionIn France and Switzerland

His success in Padua earned him an invitation from the Saclay Nuclear Research Centre, in France, to assemble a group dedicated to studying and developing bubble chambers. “His scientific reputation, of which he was quietly proud, came largely from his contribution to the development and scientific use of these instruments,” says physicist Marcus Zwanziger, a retired UNICAMP professor. Experiments and the development of experimental apparatus were his greatest vocations. “He was a physicist with an inclination towards the experimental over the theoretical,” says physicist Cylon Gonçalves da Silva, professor emeritus at UNICAMP.

Meyer spent 13 years at Saclay working with bubble chambers before he received an offer to join CERN’s team of physicists, in 1969. The job in Switzerland was permanent and the pay was excellent. He spent six and a half years working as a researcher at the Centre, before he began thinking that all his work impacted very few people. “Of course, it is essential to know how matter is made,” he said during the same 1977 interview, “but it was of no interest to the public.” His desire was also to somehow contribute to improving people’s lives, and especially the lives of Brazilians.

During this prolonged stay in Europe, Meyer and his wife often thought of returning to Brazil with their children, only to do so in the mid-1970s. Late 1973 brought with it the Yom Kippur War, a conflict involving Israel versus Egypt and Syria, which, in turn, resulted in the 1973 Oil Crisis. Meyer had already been warning Brazilian authorities and scientists of the need for a country like Brazil, with yet incipient oil exploration, to develop alternative energy sources. He conducted a brief study in 1972 on the consequences of a hypothetical fossil fuel shortage, which did not resonate. That is until Brazilian scientific policymakers recognized the skyrocketing oil prices and the need to develop alternative energy sources. Between December of 1973 and January of 1975, Brazil’s project- and research-funding entity, FINEP, invited Meyer to organize eight seminars on the topic. In 1975, FINEP granted him all the necessary funding for an ambitious alternative energy project, under the condition that he would lead the project himself.

Bruno Meyer's personal collection

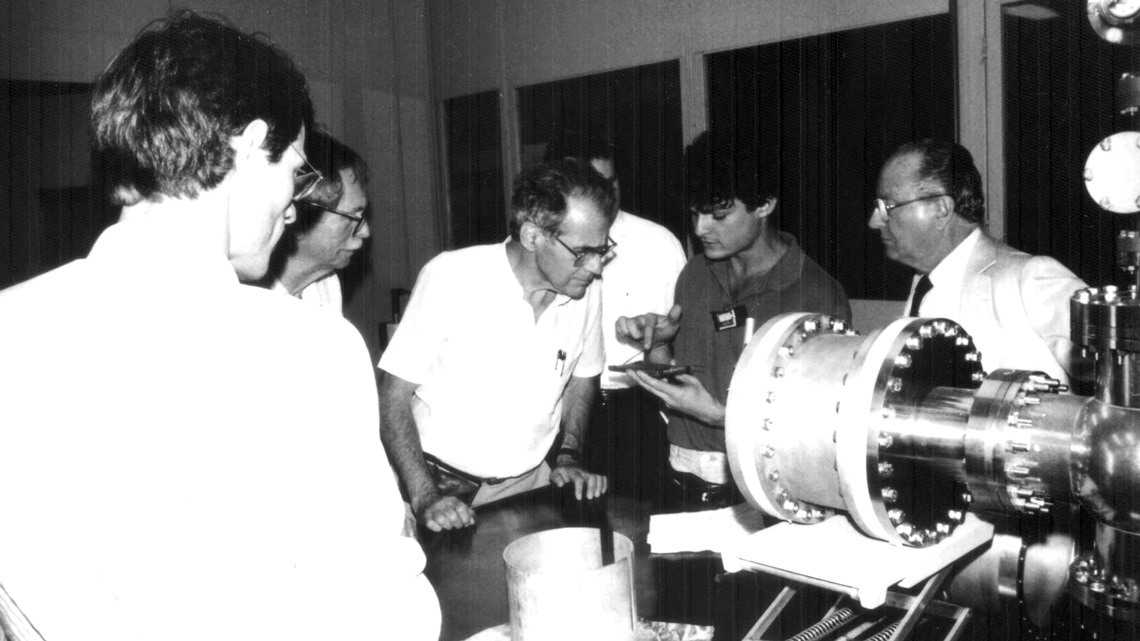

The researcher (in the middle) and the physicist Roberto Salmeron (with the mustache, to the left) at LNLS, in 1990Bruno Meyer's personal collectionExcited about the prospect of applying his research to Brazil’s development, Meyer left CERN for UNICAMP, where he organized a team that proposed using solar energy to improve crop production and to develop hydrogen-powered automobiles. “We were able to show that grains and cacao could be dried using solar energy for a fraction of the price of oil-based processes. We also showed that it was possible to make a hybrid SUV, powered by hydrogen and diesel,” says Zwanziger, one of Meyer’s closest colleagues working on the project.

It was a genuinely interdisciplinary project. “In UNICAMP’s flexible academic environment, Jean was able to connect experts with diverse abilities who, at other institutions, would work in isolation. There were physicists, mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, chemical engineers, and food engineers, all sharing projects, tasks, laboratories, ideas, support, and social lives,” recalls Zwanziger. Bruno Meyer says that he was always amazed by his father’s ability to rally people around a project and maintain friendships.

This aptitude was one of the characteristics that led the physicist to be appointed Executive Director of FAPESP’s Executive Board, a position he held from 1976 to 1980. For four years, his political ties at FINEP ensured the necessary flow of funds for alternative energy research. But the oil crisis eased, FINEP’s board transformed, the Brazilian government’s enthusiasm waned, and the money supply dried up. Zwanziger recounts that the hydrogen- and diesel-powered pickup truck drove around UNICAMP and the Barão Geraldo district, in Campinas, and impressed many people, but there was not enough visibility to arouse the interest of automakers.

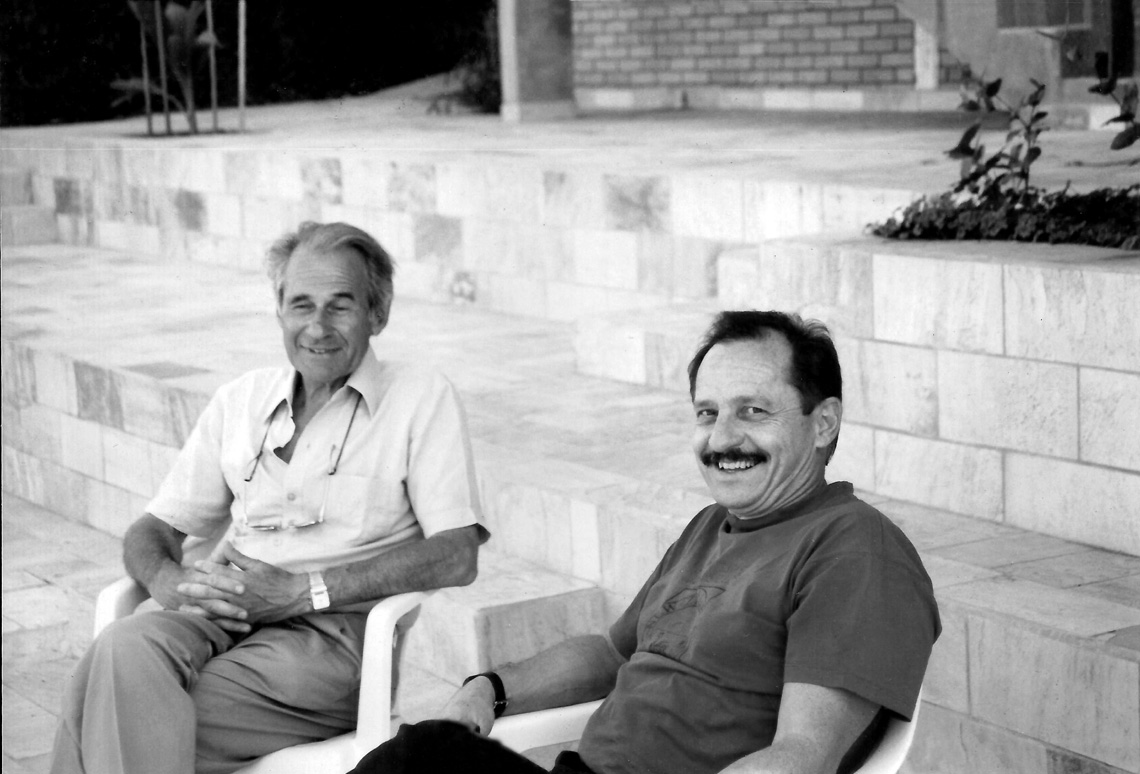

Bruno Meyer's personal collection

With Marcus Zwanziger (to the right), in Campinas, in 1995Bruno Meyer's personal collectionAccording to the researcher, they did not have the critical mass with investment capacity and supply chain mobilization to bankroll the processes for drying grains using solar energy. “It was over before it even began,” he laments. “We were on the right track, at the wrong time.” Today, for a number of reasons, including the climate crisis, renewable energy research is in full swing worldwide, and there is a renewed interest in hydrogen-powered vehicles.

Support for the LNLS

Dejected and divorced, Meyer returned to France in 1980, where he remarried and became a father for the fourth time. He was hired by the same laboratory at the Polytechnic Institute of Paris where he had worked nearly 30 years earlier. He never returned to Brazil, but his emotional ties to the country—the motif of many of his drawings and paintings, another of his skills—would still lead him to his final contribution to Brazilian science.

Meyer was a key player at the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS), in Campinas, leading projects to unlock processes for importing equipment from Europe. “We needed to import sophisticated equipment, some for civilian and military use,” says Gonçalves da Silva, who coordinated establishment of the LNLS in the late 1980s. “An import license was required from the manufacturing country, but in order to carry out purchases, you also needed authorization from the Brazilian government. The bureaucracy stalled these processes and, when one was completed, the other became invalid.”

Antoninho Perri / UNICAMP

Prototype of UNICAMP’s first hybrid vehicle at the Auto Show in 1995Antoninho Perri / UNICAMPIn 1987, when the laboratory was just being established, Meyer intervened and conceived of a bridge between CERN and the Brazilian project. “Jean explained CERN’s equipment-purchasing process to us: there was an account for each team from each participating country. When scientists requested to purchase something, CERN paid and deducted the amount from the team account of the scientists who requested the expense, without much bureaucracy,” says Silva. Meyer put him in touch with Italian Carlos Rubbia, the 1984 Nobel Prize winner in Physics and CERN’s director at the time. As a result of this meeting, a team account was opened at the Geneva center for the LNLS project, through which Brazilians were able to purchase electronic equipment needed to build the laboratory, inaugurated in 1997.

Required by French law to retire in 1990, Meyer continued to work at a program receiving foreign exchange students at ENS Lyon (École Normale Supérieure de Lyon). Building bridges, as always. He died in 2010 from a stroke at the age of 85, after living with Alzheimer’s disease for 10 years.

Republish