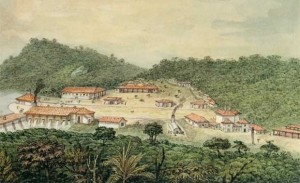

ILLUSTRATION BY J.B. DEBRET/40 PAISAGENS-RIO DE JANEIRO, SÃO PAULO, PARANÁ AND SANTA CATARINA/CIA EDITORA NACIONAL/ FAU/USP COLLECTIONThe Royal Iron Factory as painted by Debret in 1821ILLUSTRATION BY J.B. DEBRET/40 PAISAGENS-RIO DE JANEIRO, SÃO PAULO, PARANÁ AND SANTA CATARINA/CIA EDITORA NACIONAL/ FAU/USP COLLECTION

Brazil’s first major investment in steel milling started with a fiasco that went on for four years in the early nineteenth century. Despite the Portuguese government’s efforts to plan and support metallurgical enterprises, it took this industry a long time to firmly establish itself in Brazil. That there was iron ore in the states of Minas Gerais and São Paulo had been an established fact for quite a while. Therefore, in the late eighteenth century, the Portuguese sponsored the training of Portuguese and Brazilians at the best European metallurgical centers. However, it was only when the Portuguese Court moved to Brazil that the superintendent Manoel Ferreira da Câmara Bittencourt was allowed, in 1809, to establish the basis of the Patriotica plant in Gaspar Soares, now Morro do Pilar, Minas Gerais state. Almost at the same time, the Portuguese administration ordered the construction of the São João de Ipanema Royal Iron Mill (Real Fábrica de Ferro) in Iperó, São Paulo state, opened in 1810. The two concerns took years to produce any metal whatsoever. “The lack of suitable know-how and of specialized labor was only partially overcome in Brazil during the second half of the 1810’s,” says Fernando Landgraf, the Innovation director of IPT (the Technological Research Institute) and a researcher at the Polytechnic School at the University of São Paulo.

REPRODUCTION TAKEN FROM THE BOOK RETRATOS DE IPANEMA. PHOTO JULIO W. DURSKI/INSTITUTO HISTÓRICO, GEOGRÁFICO E GENEALÓGICO DE SOROCABAPhoto from 1890, five years before it was shut downREPRODUCTION TAKEN FROM THE BOOK RETRATOS DE IPANEMA. PHOTO JULIO W. DURSKI/INSTITUTO HISTÓRICO, GEOGRÁFICO E GENEALÓGICO DE SOROCABA

Portugal had always been aware of the importance of controlling the entire iron ore export cycle and of the transformation of ore into the three families of products known in the early nineteenth century: pig iron (iron with carbon content of about 4%), wrought iron (carbon content below 0.1%) and steel (carbon content around 1%). In Europe, the English, Swedes and Germans from Saxony and Hesse had the tradition of steel mills with hundreds of blast furnaces in these regions. That was where, in the first decade of 1800, the Portuguese hired Frederico Luiz Guilherme Varnhagen and Guilherme Eschwege, Germans who advised José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva in the Figueiró dos Vinhos Iron Plant in Portugal. Furthermore, it was in Sweden that the administration of the Empire hired a technical team headed by an experienced man, Carl Gustav Hedberg, to start producing the metal in Brazil. It was crucial to be familiar with blast furnace construction techniques in order to make iron successfully. “Blast furnaces run on an ongoing basis; they never stop, which makes all the difference when it comes to producing the metal,” says Landgraf, the author of a newly published article in Metalurgia e Metais, written jointly by Paulo Eduardo Martins Araújo and Sven-Gunnar Sporback, a Swede, who investigated that period. Hedberg was chosen for his experience with blast furnaces and he brought to Iperó other technicians and machines purchased abroad. The outcome, however, was disappointing. From 1811 to 1814, he built four small melting furnaces, a foundry, refining forges, canals, a waterwheel and a reservoir but he abandoned the established notion of a blast furnace, producing only three tons of very poor quality iron over four years.

To this day, there is an ongoing discussion as to what led the Swede to act in this way. “There is the hypothesis of sabotage, to avoid competition with Sweden, but I believe in the hypothesis that his technicians were rather incompetent and didn’t know how to work properly,” Landgraf evaluates. There was also another problem: ignorance of how to deal with the type of iron ore from that area. Once Hedberg was fired, Varnhagen took over the plant in 1815, finally building a blast furnace. He then hired German technicians and produced some 30 tons a year, far less than the 600 tons planned. At the other foundry (Morro do Pilar, in Minas Gerais state), the blast furnace built yielded even less. “Without the right technique, superintendent Câmara only managed to smelt iron for three days.”

Republish