In February, US President Donald Trump announced a plan to end the country’s HIV epidemic by 2030. “We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to eliminate new HIV infections in the USA,” he said at the annual State of the Union address. The aim is to reduce the number of infections by 75% in the next five years and by 90% within 10 years, preventing the infection of 250,000 people in that time frame and making the immunodeficiency syndrome a more sporadic disease. To achieve this target, actions will be taken simultaneously on several fronts.

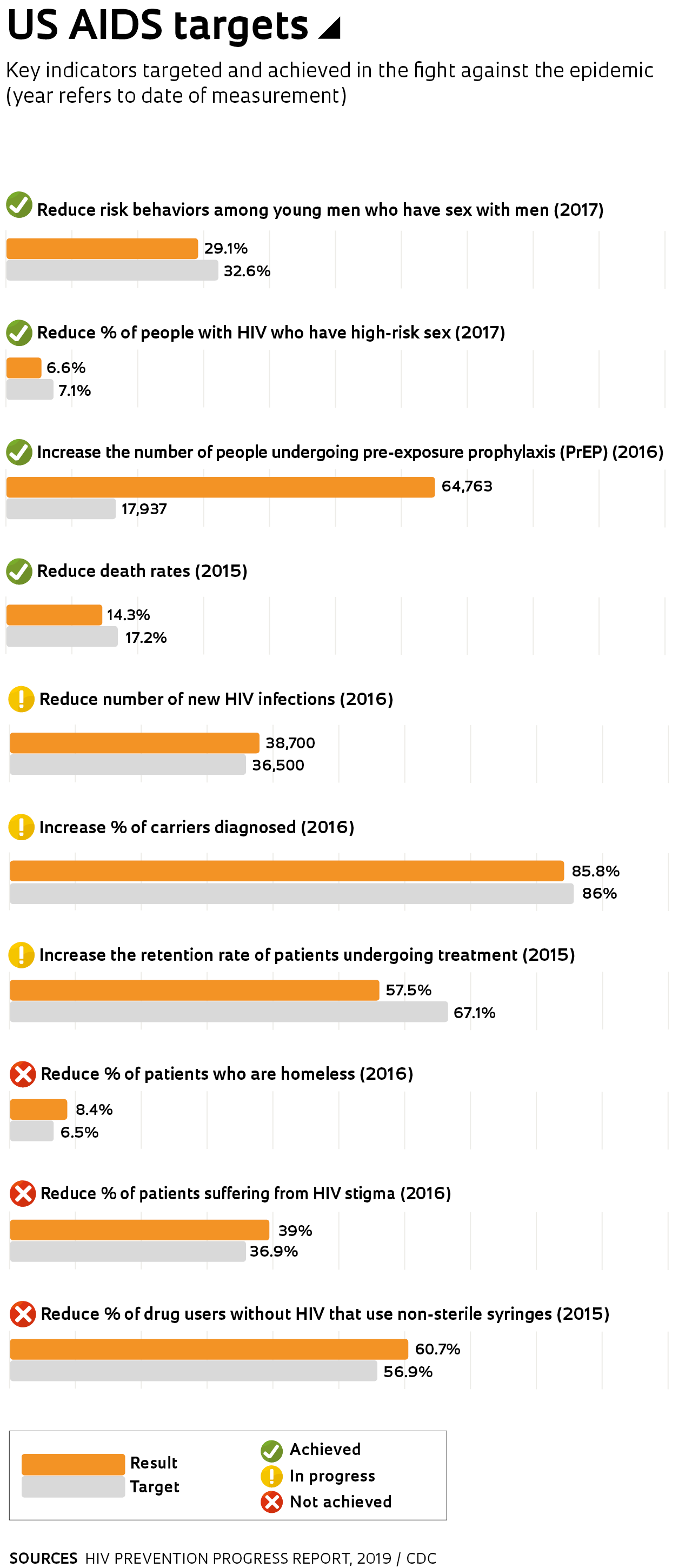

The main approach, which has already begun, is to increase the supply of diagnostic tests and antiretroviral drugs. The goal is to ensure that the 1.1 million people living with HIV in the country avoid progressing to the later stages of the disease that destroys the immune system, and to suppress the viral load in the bloodstream so that carriers no longer transmit the virus, continuing to receive treatment for the rest of their lives—or until a cure is discovered. Another strategy is to prevent roughly one million people identified as “at-risk” from acquiring the disease using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)—drugs that can reduce the risk of being infected by up to 97%. One of the major new approaches is a plan to concentrate efforts in the 48 counties where more than half of all AIDS cases in the USA occur, adopting intensive strategies for prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. Many of these hotspots are located in poor, urban areas, particularly in states such as Florida, California, Texas, and Georgia.

Judging by the progress made in recent years, Trump’s target seems to be achievable. Statistics show that the AIDS epidemic has lost momentum. According to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, an American organization that focuses on public health studies, there were 940,000 AIDS-related deaths worldwide in 2017, just half of the 1.9 million that died in 2004. In the USA, AIDS has a low prevalence among the general population, with cases primarily occurring in specific groups, such as homosexual men and sex workers. The disease affects 0.3% of the country’s population, a level similar to that recorded in Brazil, where the rate is 0.4%.

One limitation that the plan will address is the varying levels of access to healthcare available in the USA. “Unlike the Brazilian model, the USA has no universal system and care ends up differing widely from one place to another,” explains Dr. Maria Ines Battistella Nemes, a professor at the University of São Paulo Medical School (FM-USP). “In the state of New York, for example, outpatient services use electronic medical records to produce daily reports showing whose viral load is yet to be reduced. And they promptly investigate when a patient does not show up to a scheduled appointment. But this is the situation in New York, where treatment is largely subsidized. Residents in many other states face very different circumstances; even access to drugs can be difficult for some,” she says.

In 2018, Nemes spent six months at the New York State Department of Health studying patient care to support her work as head of the QualiAids project, a tool for evaluating outpatient services under the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) for people with HIV in Brazil. QualiAids is currently in its fourth iteration, providing 84 health service indicators. “Health clinics answer a series of questions about care time, technological and financial resources, treatment options, and medication. Each question results in an indicator,” she says. The survey classifies services into four different levels and helps health teams and departments improve.

While the American plan is clear about its methods and objectives, there are doubts about its ability to change behavior. Although AIDS has declined in the general population, it has grown among young men in the USA. And even in places where cases have been reduced, it has not been possible to actually eliminate the disease. San Francisco, California, had 2,000 cases per year in the 1990s, and now sees just 200 cases annually. “We’ve hit a wall. All the gay white boys are on PrEP, but now we have to reach the hard-to-reach,” Jeff Sheehy, an AIDS activist from the city, told The New York Times. “HIV is now a disease of poverty, and you can’t separate it from people’s other issues.”

Brazil has the same problem. “The fact that the technology needed to end the epidemic exists does not necessarily mean that we can do it,” says Maria Amélia Veras, a professor at the Santa Casa de São Paulo School of Medical Sciences who studies and monitors more at-risk groups such as transgender women and homosexual men. According to Veras, transgender women in particular are highly vulnerable. “The homeless, unemployed, and uneducated are not always covered by or given priority for prevention and treatment,” she says.

Veras led a study that identified an HIV infection rate of 15.4% among homosexual men and transgender people who frequent bars and nightclubs in the center of São Paulo. She is currently working in partnership with two researchers from the University of California, San Francisco, investigating how to improve the health of transgender women living with HIV. The project is funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Scheduled to end in 2020, the study monitors groups with and without HIV to try to understand the barriers that stop people from continuing with treatment. The researchers believe it is crucial that we create new ways of reaching vulnerable groups and engaging them in prevention and treatment strategies. “Unfortunately, we are seeing increased prejudice against homosexuals and transgender people,” Veras says.

Traditional channels for reaching at-risk populations are not working. “We communicate badly,” says Veras, noting that young people increasingly mediate their sex lives via mobile dating apps, and they are not influenced by more traditional prevention methods such as television campaigns. As an example of a successful approach, she highlights the Dean Street public sexual health clinic in London, which offers free testing and immediate treatment for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in a relaxed and cheerful environment. “They successfully attract young people, have them fill out a questionnaire, classify their risk level, test them, and even if the result is negative, they give them an electronic card to monitor their health care going forward,” she says.

The AIDS epidemic began in the early 1980s and in its early days, it was a huge problem for groups such as male homosexuals, intravenous drug users, and hemophiliacs who were infected via blood transfusions. At that time, the syndrome was seen as a death sentence, since there was no effective treatment. In the 1990s, drugs capable of reducing the viral load were introduced, and AIDS, although incurable, became more of a chronic disease with increasing survival rates. AIDS policy reached a turning point in around 2010, based on mounting evidence that HIV patients treated with modern drug combinations maintained an undetectable viral load and no longer transmitted the disease. “The discovery that patients with an undetectable viral load no longer transmit the virus has changed the way we fight the disease,” says Nemes, from FM-USP. Before, the main approach was to treat individuals with symptoms and publicize prevention methods. The model adopted by the George W. Bush administration (2001–2009) was known as the ABC approach: A for abstinence, B for be faithful, and C for use a condom.

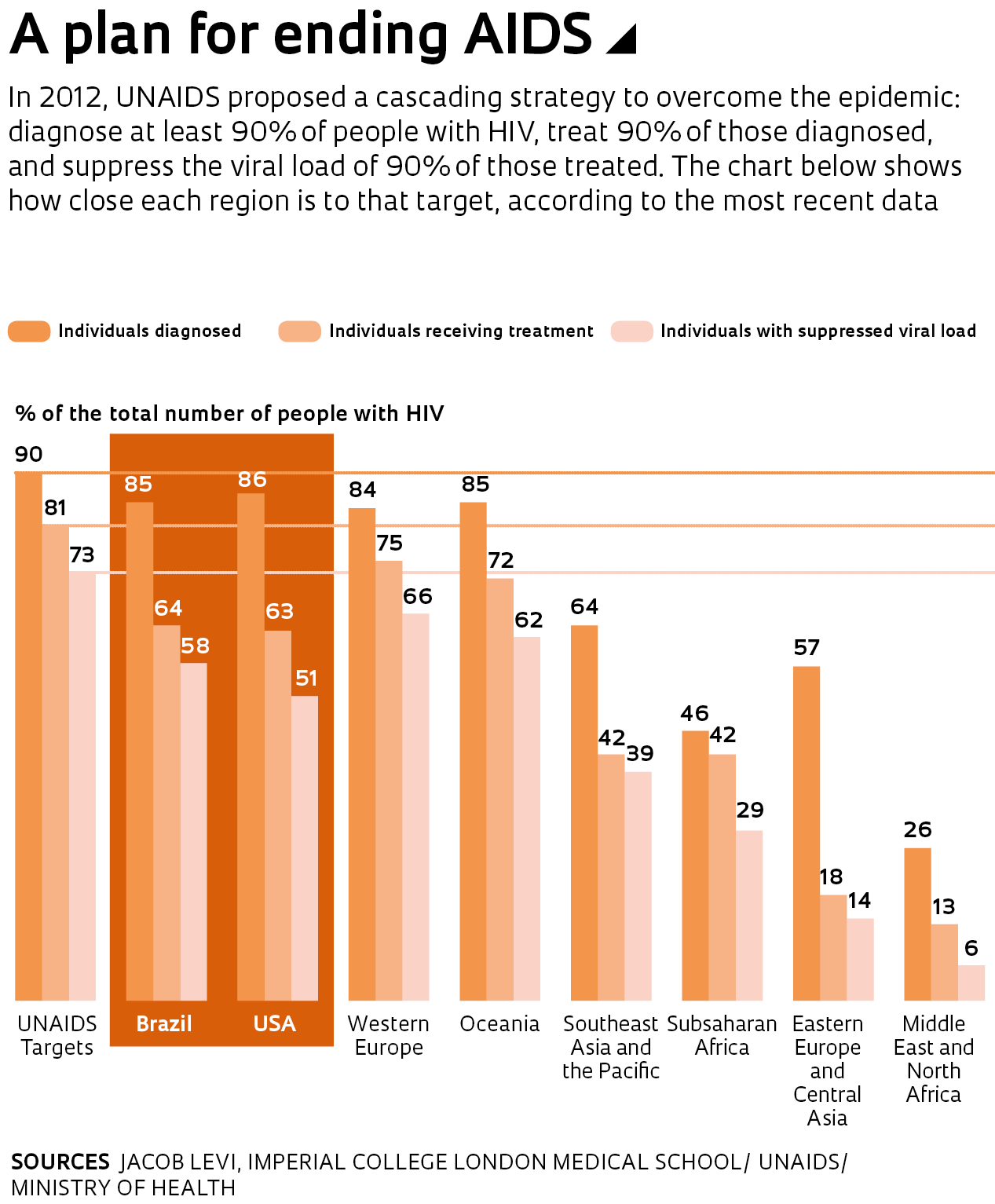

The latest findings have given rise to a more multi-faceted approach designed to identify as many cases as possible and ensure everyone diagnosed receives drug treatment. “Treatment has now become part of the prevention,” says Maria Ines Nemes. , which aims to diagnose at least 90% of those infected, treat 90% of those diagnosed, and achieve viral suppression of 90% of those being treated—the strategy should help to reduce the number of new cases by up to 75%. In recent years, many countries have made progress toward this goal, but few have managed to follow the example set by Switzerland and Italy, which have successfully diagnosed 90% of cases. The Brazilian Ministry of Health estimates there are 860,000 people living with HIV in the country. Of this total, 731,000 (85%) know of their status, 548,000 are receiving treatment, and 503,000 have a suppressed viral load.

The changing tactics in the fight against AIDS has led to the adoption of strategies designed to accelerate diagnosis. In Santo André, São Paulo State, researchers from Instituto Adolfo Lutz and the Municipal Health Department are assessing the impact of tools that can be used to identify infected individuals faster. The team performed a pilot test of an innovative screening strategy that uses an algorithm to identify people who may have recently caught the disease. Soon after contracting HIV, at least half of those who carry the virus experience short-term symptoms common to other viruses, such as a high fever, sore throat, diarrhea, and swollen lymph nodes. The algorithm uses information provided by the patient, such as the symptoms they are suffering and whether they have had unprotected sex in the past six weeks, to suggest whether they should be tested for HIV. The algorithm can recommend more sensitive viral load tests and rapid fourth-generation tests, which are capable of diagnosing cases missed by routine SUS examinations.

In 2015, a study published by the team showed that four patients who turned to the public health system with suspected dengue fever actually had acute HIV, but the tests needed to make a diagnosis were not performed. At that time, the patients were in a period known as the immunological window, when they can already infect other people but are not yet easily diagnosed. Quick tests performed at public clinics can only detect antibodies a month after infection, but techniques such as viral load counts can identify the virus in the blood much sooner, about a week after infection.

The experiment, conducted at a clinic in Santo André, showed that training the team to recognize potential cases reduced the average time between admission and antiretroviral treatment from 82 days to 28 days. “The investment is worth it because it enables the patient to begin treatment sooner after diagnosis and removes them from the chain of infection faster,” says infectious disease specialist Elaine Monteiro Matsuda, from the Santo André Health Department. “The project also has an impact by stimulating research into health services and at regional centers that function solely as laboratories,” says biologist Ivana Campos, coordinator of the initiative.

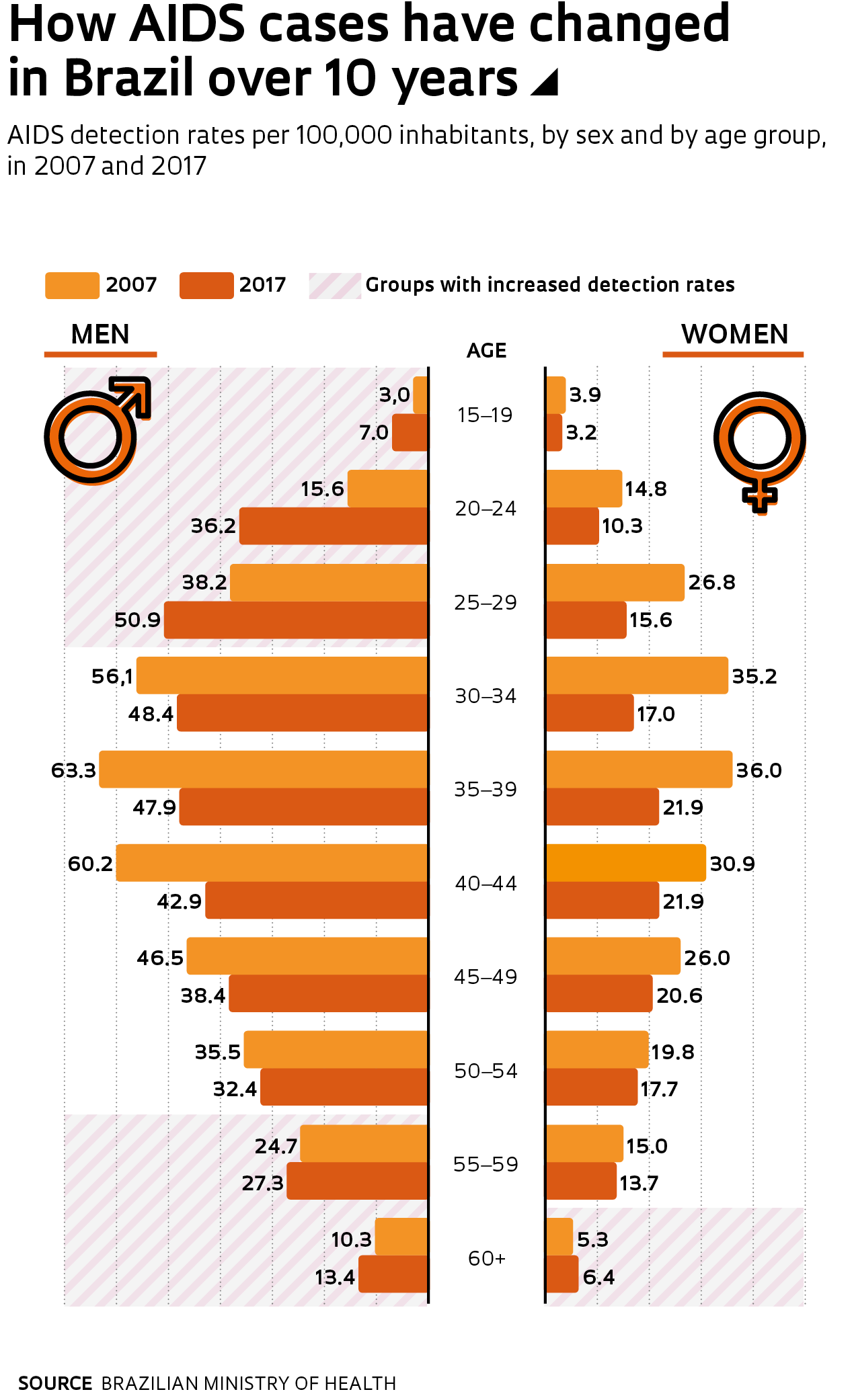

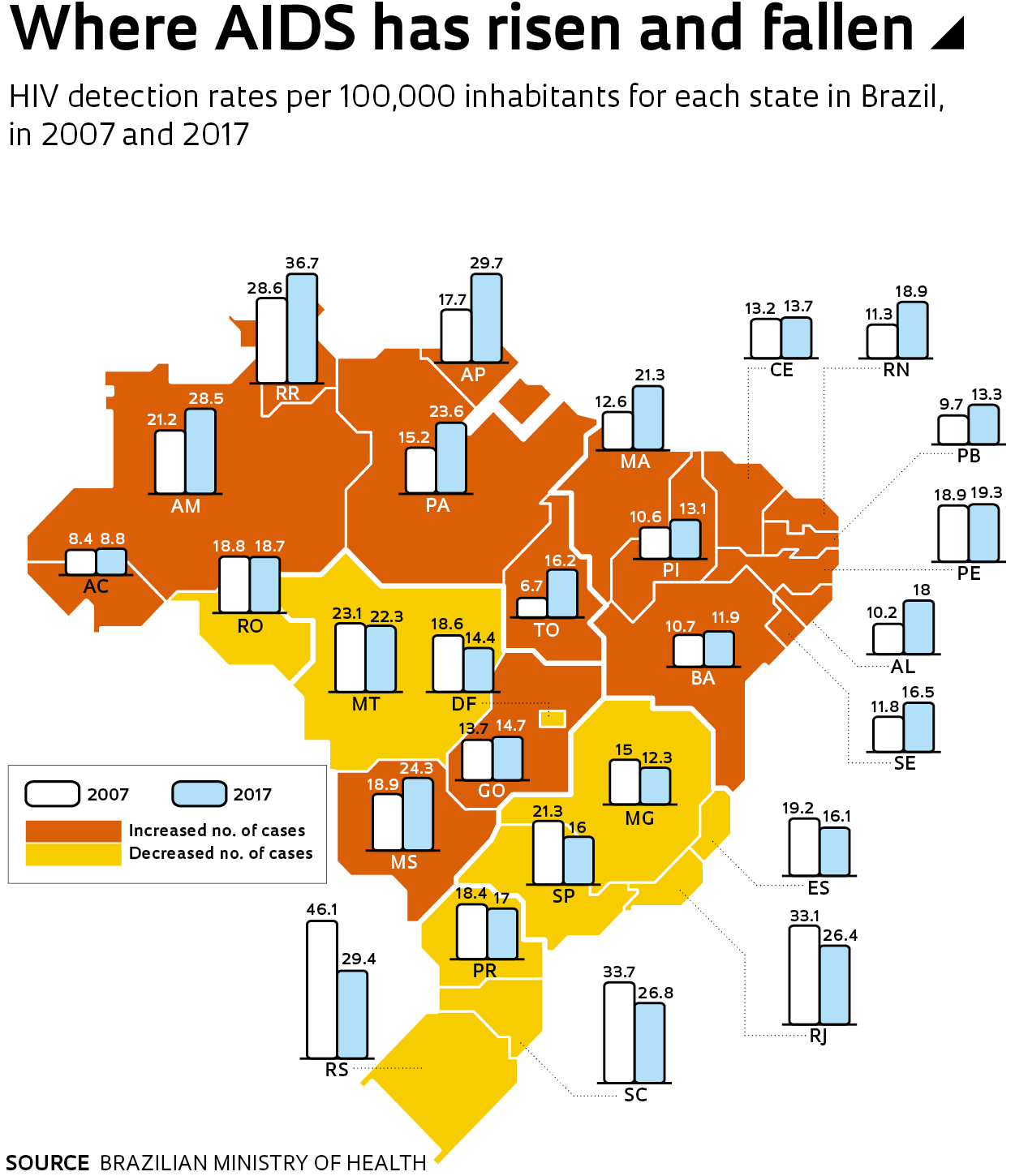

Brazil was a pioneer in providing drugs to HIV patients, and the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target is in its sights. “The aim is prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment for all,” says Gerson Pereira, director of the Ministry of Health’s Department for Monitoring, Prevention, and Control of STIs, HIV/AIDS, and Viral Hepatitis. The approach has had positive results. The detection rate was 21.5 cases for every 100,000 people in 2013, and today it has fallen to 18.5 cases, according to the ministry. Infection rates declined among women but increased among young men—in the 20–24 age bracket, the detection rate more than doubled between 2007 and 2017.

For every woman with AIDS today, there are 2.2 men in the same situation. Among sex workers, the infection rate is just over 5%, for men who have sex with men, it is around 18%, and among transgender people it could be as high as 30%, depending on the study. But antiretroviral drugs are available to everyone living with HIV, suggesting other strategies must be performing below their potential. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is used by about 8,000 Brazilians, a number too low to represent a real barrier to the disease’s progress. “The use of PrEP is highly concentrated in homosexual men of higher socioeconomic profiles. The challenge is to extend it to groups that have higher infection rates, such as young men with low incomes, sex workers, and transgender people,” says sociologist Alexandre Grangeiro, a researcher at FM-USP who coordinated one of the first studies into the use of PrEP in five Brazilian cities. He points out that in order to receive treatment, individuals have to follow a complex protocol, including visiting the clinic every three months and undergoing examinations and consultations to monitor the safety of the drug or the occurrence of sexually transmitted infections.

Maria Amélia Veras believes we need to make more progress on other fronts. “Prophylaxis is effective even when started up to 72 hours after a contraceptive failure or unprotected sex. The drug course helps prevent the infection from establishing itself and is offered by various health services, but it needs to be available at all emergency rooms if it is to have a real impact.” Gerson Pereira, from the Ministry of Health, thinks it is too soon to be talking about the end of AIDS, but says that a reduced incidence among the hardest hit groups will be evident in the coming years. He highlights the effort being made to reduce the number of deaths related to the disease, which currently stands at around 12,000 a year in Brazil. “Many deaths are caused by opportunistic diseases, including tuberculosis. Our department has incorporated care for this disease and is implementing specific prevention and treatment actions for it.”

Projects

1. Monitoring and improving the quality of health services involved in the care continuum for HIV, STDs, and viral hepatitis (nº 17/26021-5); Grant Mechanism Grant for Research Abroad; Principal Investigator Maria Ines Battistella Nemes (FM-USP); Investment R$80,551.25.

2. Evaluation of the use of molecular biology plasma viremia detection technology to identify and treat patients in the acute phase of HIV-1 infection (nº 16/14813-1); Grant Mechanism Research Grant – PPSUS; Principal Investigator Ivana Barros de Campos (Instituto Adolfo Lutz); Investment R$171,128.01.