Publicity The World of Lygia Clark Cultural Association

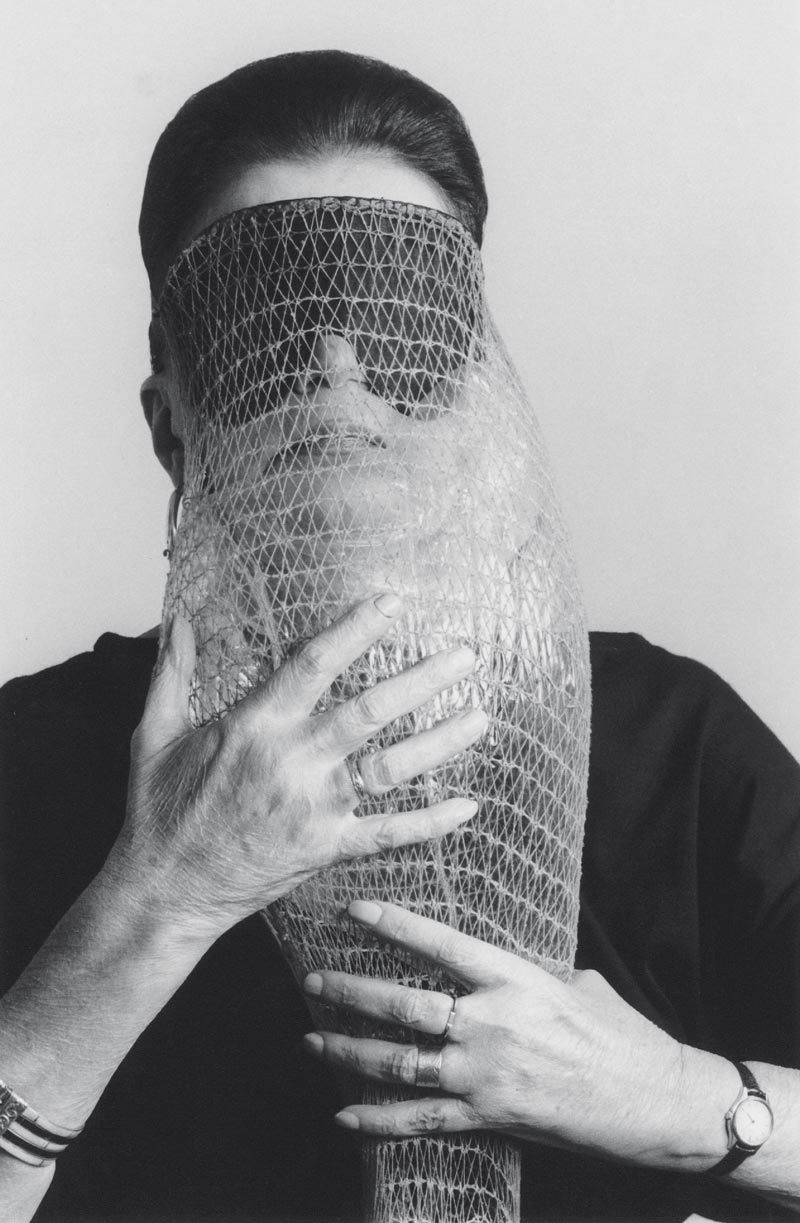

In the 1968 work Máscara Abismo (Abyss Mask), the artist proposes replacing esthetic experience with sensory experiencePublicity The World of Lygia Clark Cultural AssociationOn the 100th anniversary of the birth of Lygia Clark (1920–1988), the work of the Minas Gerais artist, considered one of the founders of contemporary Brazilian art, continues to provoke researchers from various areas of knowledge. Initially focused on the innovations of her first paintings of the 1950s, research on the artist currently seeks to investigate the meaning and up-to-datedness of her esthetic and therapeutic experiments developed after the 1960s, as well as interpret Clark’s career from a gender perspective.

Born in Belo Horizonte to a family of judges, at 18 years of age, Clark married civil engineer Aluízio Clark Ribeiro. The couple soon moved to Rio de Janeiro, where their three children were born. In 1947, she began her career as an artist under the guidance of visual and landscape artist Roberto Burle Marx (1909–1994). In 1950, during a stint in Paris, she studied under cubist painter Fernand Léger (1881–1955), painter and printmaker Arpad Szenes (1897–1985), and sculptor and painter Isaac Dobrinsk (1891–1973). Back in Rio, she joined the Grupo Frente, which, from 1959 to 1961, brought together neo-concrete artists such as Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980) and Lígia Pape (1927–2004), intent on producing works involving geometric abstraction. Their goal was to move away from modernist paintings, which were figurative and nationalist. According to art historian Maria de Fátima Morethy Couto, from the Institute of Arts of the University of Campinas (IA-UNICAMP), both this neo-concrete group, and the group of concrete artists and poets formed in the 1950s in São Paulo, represent common axes of her work: the desire to break away from the modernist esthetic. “But while concretism is closer to design, neo-concretes seek to bring the viewer closer to the development of a piece of art,” she compares.

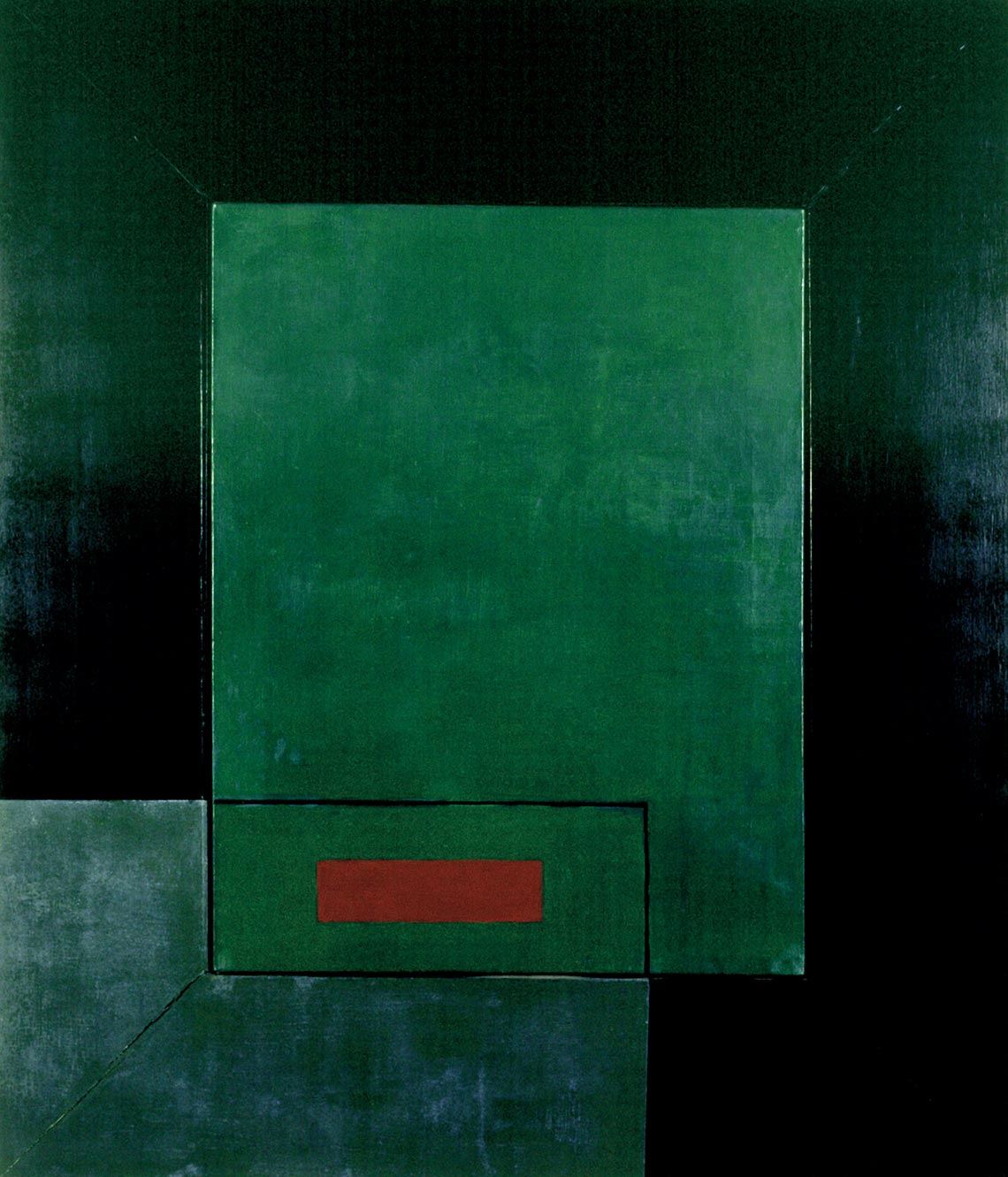

Immersed in this cultural context, Clark helped establish a turning point in Brazilian constructive art by promoting the expansion of geometric painting into real spaces, according to Ricardo Nascimento Fabbrini, a professor at the Department of Philosophy of the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences of the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP). Fabbrini explains that Clark’s first paintings, produced between the late 1940s and early 1950s and rarely shown, contain a geometry that incorporates both the sinuosities of Burle Marx and Léger’s cubism—who were her teachers—and the translucency of the Swiss Paul Klee (1879–1940) and the straightness of the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872–1944). “In this period of formation, one can clearly see her interest in moving beyond the limits of the painting, surpassing the edges or moving forward, through the contrast between colors,” he considers. As part of this movement, Clark painted Quebra da Moldura [The Breaking of the Frame], in 1954. “In it, the frame becomes the focus of the composition, while the painting, turned into a background, projects itself into the space of the world,” points out Fabbrini.

Publicity The World of Lygia Clark Cultural Association / Rodrigo Benevides

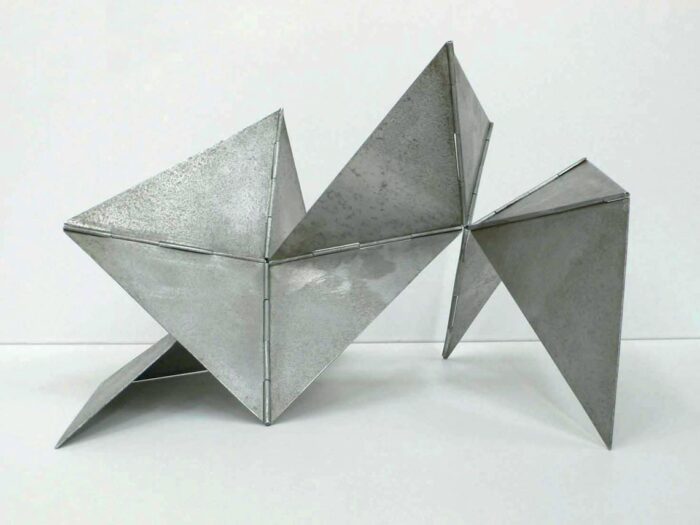

Clark integrates the frame into the body of the painting in Composição no 5: Série Quebra da Moldura (Composition No. 5: The Breaking of the Frame series)Publicity The World of Lygia Clark Cultural Association / Rodrigo BenevidesThe researcher mentions that, later, from 1960 to 1964, she produced Contra-relevos (Counter-Reliefs), Casulos (Cocoons), Trepantes (Climber), and Bichos (Animals). The goal was to conquer the space on the front of the piece through the overlapping of metal plates. In Contra-relevos, explains Fabbrini, the folding and unfolding of planes creates two- or three-dimensional spaces, while in Casulos the metal plates advance even further into the external space. “The ‘cocoons’ then fall from the wall to the floor. And out of these fallen cocoons, animals with beaks emerge,” he describes as he explains the process for creating Bichos, probably Clark’s best-known series. Made of aluminum or tin plates, the Bichos have hinges, allowing the viewer to move them and change their shape. “The pieces need to be activated by the handler. From the beginning, Clark’s work expresses a desire to break away from the traditional structure of the canvas. With Bichos, the canvas meets the spectator through movement,” observes professor and curator Talita Trizoli, who researched the topic for her PhD. Today, as a postdoctorate student at the Brazilian Studies Institute (IEB) at USP, she is developing a project on female art critics.

For art historian Paula Priscila Braga, from the Federal University of ABC (UFABC), Clark’s work challenges the idea that a work of art is an inert object to be contemplated. “Clark believes the pieces exist to continue to build who we are psychologically,” she says. “When the plates in Bichos are turned, they show cracks in the world that we assume to be real. Thus, these pieces represent the idea that reality is not the smooth and shiny aluminum plate, but rather what is behind it, that is, our relationship with the things of the world,” proposes the historian. In its different phases, Clark’s career is guided by an evolutionary logic based on the metaphor of the organism, considers Fabbrini. “That is, she is developing in the same way that a cell becomes tissue, tissue becomes a system, a system becomes a tract, and a tract becomes a living being,” he explains.

Publicity The World of Lygia Clark Cultural Association

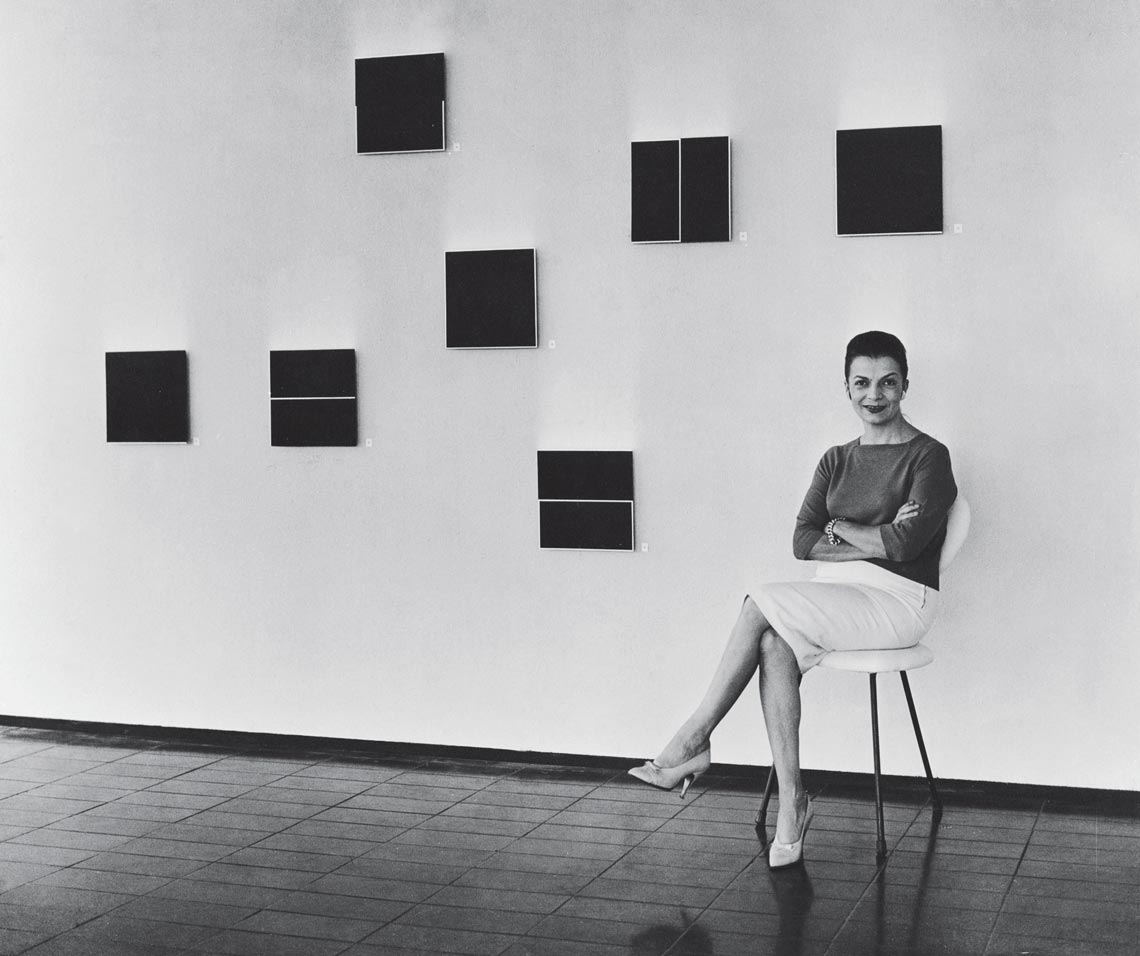

The artist during the 1959 National Exhibition of Neo-concrete Art, in Rio de JaneiroPublicity The World of Lygia Clark Cultural AssociationIn Arquivo para uma Obra-Acontecimento [Archive for an Event Piece], a 2011 box set containing 20 DVDs, interviews, and reflections from those who knew Clark, psychoanalyst and art critic Suely Rolnik, from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP), reports that, during a 1963 study for the development of one of Clark’s Bichos, as she cut some paper for a Moebius strip—a shape obtained by pasting the two ends of a strip together after rotating one of them—Clark realized that the piece consisted of the experience of cutting the material itself, not of the object that resulted from the cut. In one of her texts, Rolnik shares that the experience led the artist to develop a new path of investigation, involving the interference of her works in the human body. At that time, Clark called herself a “proposer,” or a “non-artist,” refusing the fetishism of art in defense of an esthetic state,” explains Fabbrini. With this perspective, from the 1960s to the 1970s, her individual or group proposals became constructive and could be freely experienced by the public. “One example is Respire Comigo [Breathe with Me], an experience in which a plastic bag filled with air with a rock on it must be pressed to reproduce the experience of breathing, reverberating throughout the participant’s body,” he describes.