In 1964, during a preparatory expedition for the National Archaeological Research Program (PRONAPA), archaeologist Valentín Calderón (1921–1980) was returning from Curitiba to Salvador in a newly purchased Rural Willys and decided to rest in Rio de Janeiro. The car was stolen but recovered the same day by police, who had been searching for another vehicle of the same make belonging to then-mayor Carlos Lacerda (1914–1977). For American archaeologist Betty Meggers (1921–2012), the incident was a sign of good luck for the newly launched program. Over the next five years, PRONAPA carried out fieldwork along the entire Brazilian coast and parts of the Amazon, transforming the working methods of Brazilian archaeology.

Before PRONAPA, archaeologists in Brazil typically focused on exploring as much as possible at a single site and lacked standardized methods for classifying artifacts, making it difficult to compare findings from different locations. The program introduced uniform excavation techniques using small spatulas, brushes, sieves, and spreadsheets to document sites and artifacts, aligning Brazil with international practices. Rather than concentrating solely on a few sites, PRONAPA prioritized mapping multiple locations throughout Brazil and developing a consistent methodology for classifying and comparing artifacts. Through this work, archaeologists deepened their understanding of populations dating back 5,000 years who built vast shell mounds—known as sambaquis—along the Brazilian coast. They also studied inland and Amazonian sites and identified traditional techniques used by Indigenous peoples to produce ceramic vessels.

MAE-USPExcavations at the José Fernandes archaeological site in Itaberá, São Paulo, in 1968MAE-USP

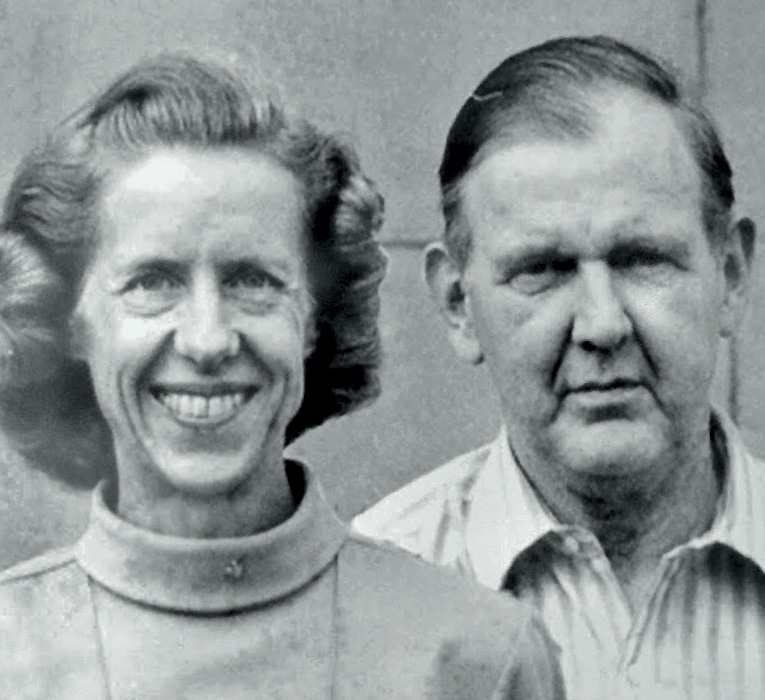

In 1962, archaeologist José Loureiro Fernandes (1903–1977), of the Center for Archaeological Studies and Research at the Federal University of Paraná (CEPA-UFPR), organized a training course for one of the first generations of professional archaeologists in Brazil. Taught by French archaeologist Annette Laming-Emperaire (1917–1977) and Margarida Andreatta (1922–2015) of CEPA, the course included hands-on excavation at a sambaqui in Paranaguá, on the Paraná coast. PRONAPA emerged from another course organized by Fernandes in March 1964, led by Meggers and her husband, Clifford Evans (1920–1980), which brought together archaeologists from across the country.

“The courses were important because our training was still very empirical,” says archaeologist Ondemar Dias of the Brazilian Institute of Archaeology (IAB) in Rio de Janeiro, who participated in PRONAPA. Until the first graduate program in archaeology, which began in 1972 at the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of the University of São Paulo (MAE-USP), and the launch of the first undergraduate program in 1975 at Estácio de Sá University in Rio de Janeiro, most archaeologists came from backgrounds in history, anthropology, or geography.

“We didn’t have standardized terminology to classify ceramics, stone artifacts, and other objects, and archaeologists couldn’t fully understand each other’s work,” explains geographer and archaeologist Silvia Maranca, a retired professor at MAE-USP. “Research focused mainly on the large shell mounds on the coast known as sambaquis. There were almost no excavations at inland ceramic sites. PRONAPA changed that.”

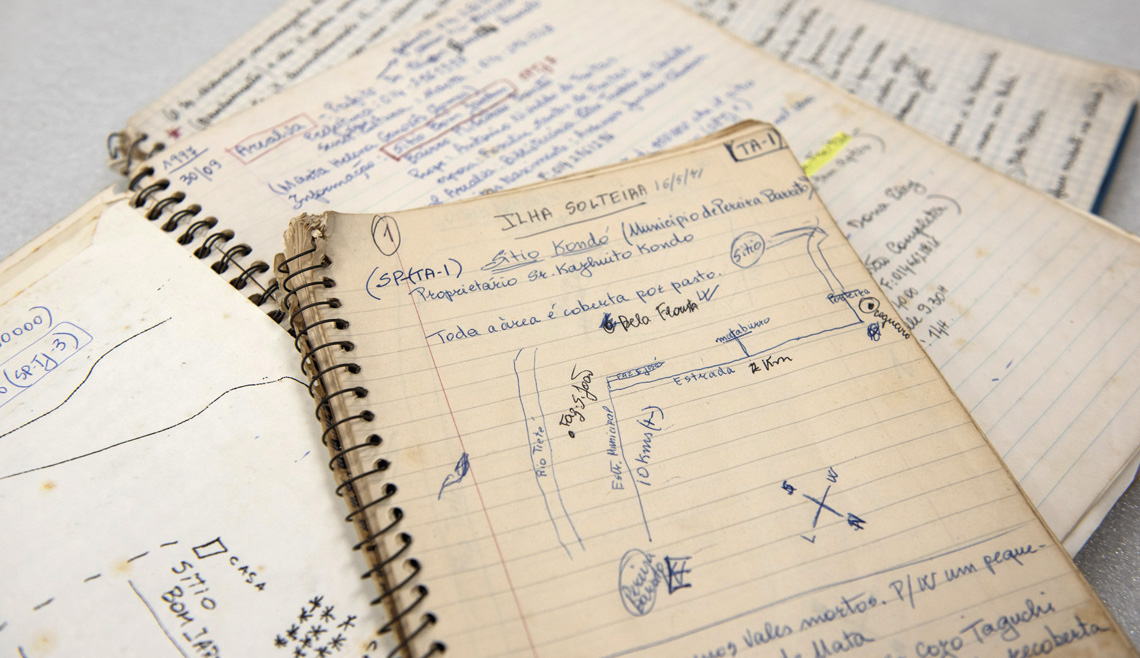

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP Field notebooks of archaeologist Silvia Maranca, a participant in PRONAPALéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP

Geographer Igor Chmyz, who specialized in archaeology and was then at UFPR (now retired), helped teach the 1964 course. Having studied and worked on expeditions with foreign archaeologists, Chmyz introduced classification and analysis methods for ceramics. These methods were based on terminology that, two years later, would form the basis of the first manual for studying Brazilian ceramics, published in the journal Manuais de Arqueologia.

Meggers introduced the Ford method of analysis and seriation, developed by American archaeologist James Ford (1911–1968) in the 1940s and 1950s. Seriation involves studying the similarities and differences between objects to establish a sequence and determine their relative age. “The method was important for PRONAPA because it can be used to interpret any class of object,” says Dias.

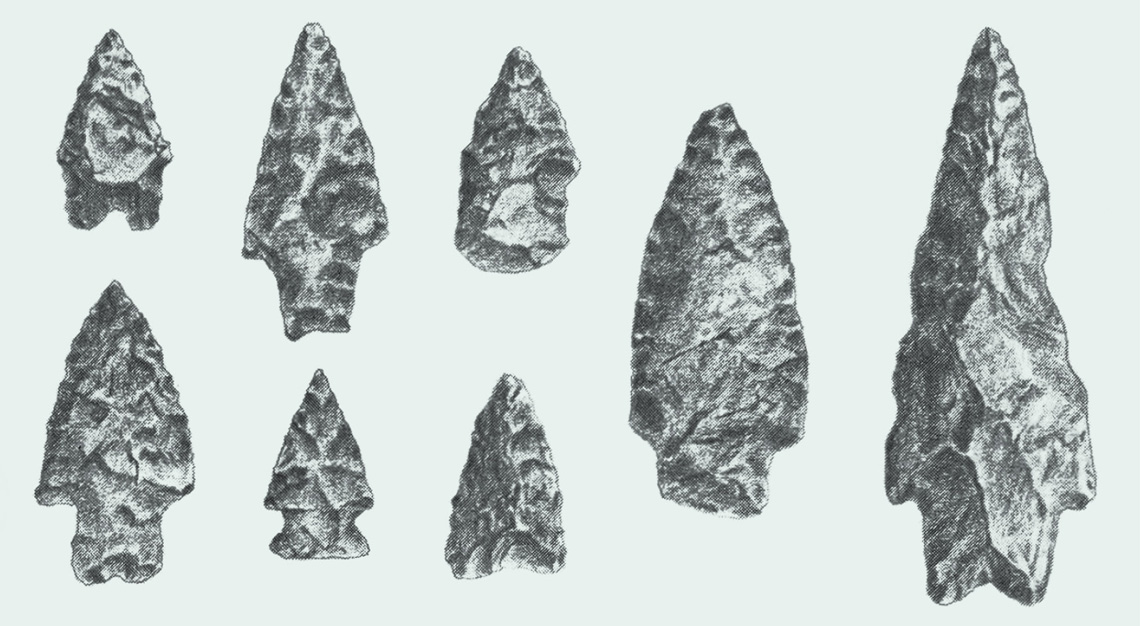

JENNINGS, J. D. Ancient Native Americans. 1978 Projectile points made by Indigenous peoples who inhabited southern Brazil around 12,000 years agoJENNINGS, J. D. Ancient Native Americans. 1978

After the courses, from October 30 to November 22, Meggers and her husband, Clifford Evans (1920–1980), with support from the Fulbright Commission of the United States and the UFPR Research Council, visited archaeologists in Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Norte, Pará, and Brasília. Their goal was to learn more about archaeology in Brazil and develop the PRONAPA proposal. At the end of the trip, they created a three-year plan in which each researcher was to identify three river valleys (soon increased to five) that “may have served as migration and communication routes,” as Meggers described in an article published in Arqueologia magazine in 2007, the same article in which she recounted the recovery of the Rural Willys.

JENNINGS, J. D. Ancient Native Americans. 1978 Sculpture created between years 1000 and 500 by ancient peoples of the Amazon lowlandsJENNINGS, J. D. Ancient Native Americans. 1978

By 1968, program participants had visited 22 regions in nine states and recorded more than 1,000 archaeological sites. The research provided greater insight into the populations of the sambaquis in Santa Catarina, Paraná, and São Paulo who had lived in Brazil for over a thousand years. These groups used knives and stone fragments to cut or skin slaughtered animals and crafted other tools from rounded stones, known as choppers. They also made arrowheads from stone, shell, and bone, and produced polished axes and pendants using polished stones and fish vertebrae.

PRONAPA archaeologists studied ceramics from across the country and, using seriation methods, identified what they called the Tupiguarani Tradition along with other regional traditions concentrated in southern and southeastern Brazil. These traditions refer to the ways ancient populations in specific areas created and decorated ceramic vessels. The vases and pots varied in the composition of the clay and in decorative techniques, which included painting, brush marks, fingerprints, and incisions made with nails or sharp tools.

Maranca participated in these discoveries in São Paulo. “We carried out excavations on farms and on land where the government planned to build power lines,” she says. “We couldn’t excavate systematically at the power plant construction sites because we had to keep up with the pace of the work. But we did conduct deep excavations to uncover ceramics and stone artifacts in Fernandes and along the banks of the Paraná and Tietê rivers.”

Archaeologists concluded that the Indigenous peoples of the Amazon who created ceramics decorated with red and white paint or marked with raised patterns, associated with the Tupiguarani Tradition, lived in “forest regions suitable for seasonal cultivation.” Those who produced ceramics tied to regional traditions inhabited “other types of environments, which favored their survival,” according to a 1970 report.

Natural barriers, particularly rivers, limited contact between Indigenous groups on the coast and those in the Amazon interior before European colonization. “The studies of the 1960s and 1970s, even though later revised conceptually, were the first nationwide investigations into the lives of Indigenous peoples before the arrival of Europeans,” says archaeologist João Carlos Moreno of the Federal University of Rio Grande (FURG), who did not take part in the program.

Jéssica M. Cardoso / MAE-USPSambaqui on the coast of Santa Catarina, formed by shells, sand, and traces of fire between 1,300 and 500 years agoJéssica M. Cardoso / MAE-USP

PRONAPA officially concluded in 1973 with a symposium at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. One of the participants, archaeologist Mário Simões (1914–1985), then at the Goeldi Museum, noted that the program had focused largely on areas outside the Amazon and that more research was needed in the forest. He proposed the creation of the National Program for Archaeological Research in the Amazon Basin (PRONAPABA), which began in 1976. Dias coordinated research in the Purus River basin in Acre, where he discovered the structures now known as the Acre geoglyphs (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 346).

For years, archaeologists studied the dark, fertile soil formed by organic matter left by ancient Amazonian populations, known as terra preta, and classified ceramic fragments into phases such as Tucuruí, Tauá, Marabá, and Itupiranga. Ultimately, they continued efforts to trace the movements of ancestral Indigenous peoples.

CEPA-UFPR The organizers of a 1956 course: Joseph Emperaire (left), Annette Laming-Emperaire, and José FernandesCEPA-UFPR

PRONAPABA identified and registered 334 archaeological sites in the Amazon, most of them in the state of Amazonas, which accounts for 119. Today, there are 467 sites in the state listed in the database of the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN). Through this mapping, archaeologists concluded that ancient populations living in floodplain areas, which are subject to periodic flooding, produced elaborate ceramics, such as those of the Marajoara tradition. In contrast, those living on terra firma employed simpler techniques. Another key finding was that differences in the composition of seemingly identical clay could indicate distinct phases within the same ceramic tradition. This helped archaeologists distinguish between sites that had been continuously occupied by large populations over time and those that experienced more sporadic, short-term occupation.

As PRONAPA archaeologists focused primarily on ceramics, research on other artifacts, such as stone tools, was limited. “After PRONAPA, in the late 1970s, Meggers and Evans introduced the Umbu tradition to classify all arrowheads found in rock shelters or open-air sites. It’s like saying all Indigenous people who made ceramics were Guarani,” criticizes Moreno. In recent studies, he concluded that the cultural diversity of the early Indigenous peoples of southern and southeastern Brazil, where the Umbu tradition was thought to predominate, was far greater than previously recognized.

CEPA-UFPR The creators of PRONAPA: Meggers and Evans in 1964CEPA-UFPR

In the Amazon, revisions were even more significant. In the 1990s, American archaeologist Anna Roosevelt challenged PRONAPA and PRONAPABA’s conclusion that dryland sites in the region were small, recent, and sparsely populated. She discovered sites dating back as far as 11,000 years and dated the oldest known pottery in the Americas—found at the Taperinha archaeological site—to 8,000 years ago (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 387).

In the same decade, American archaeologist Michael Heckenberger discovered large sites with underground ditches that may have served as defensive structures, along with evidence of extensive villages connected by pathways built by Indigenous peoples of the past. Brazilian archaeologist Denise Schaan identified massive geometric earthworks etched into the Amazonian soil by Indigenous peoples. Some of these sites have even been described as ancestral urban centers. To this day, archaeologists continue to study and uncover new, complex structures built by the ancient peoples who once inhabited the territory that would become Brazil (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 333).

The story above was published with the title “New methods for unearthing the past” in issue 353 of July/2025.

Scientific articles

MARANCA, S. A arqueologia brasileira e o Programa Nacional de Pesquisas Arqueológicas (Pronapa) dos anos 60. Arqueologia. Vol. 4, pp. 115–23. 2007.

MEGGERS, B. J. A contribuição do Brasil à interpretação da linguagem da cerâmica. Arqueologia. Vol. 19, no. 3. 2007.

PRONAPA. Brazilian archaeology in 1968: An interim report on the National Program of Archaeological Research. American Antiquity. Vol. 35, no. 1. Jan. 1970.

SIMÕES, M. F. Programa Nacional de Pesquisas Arqueológicas na Bacia Amazônica. Acta Amazonica. Vol. 7, no. 3. 1977.

Book

JENNINGS, J. D. (ed.). Ancient Native Americans. Freeman, San Francisco, 1978.