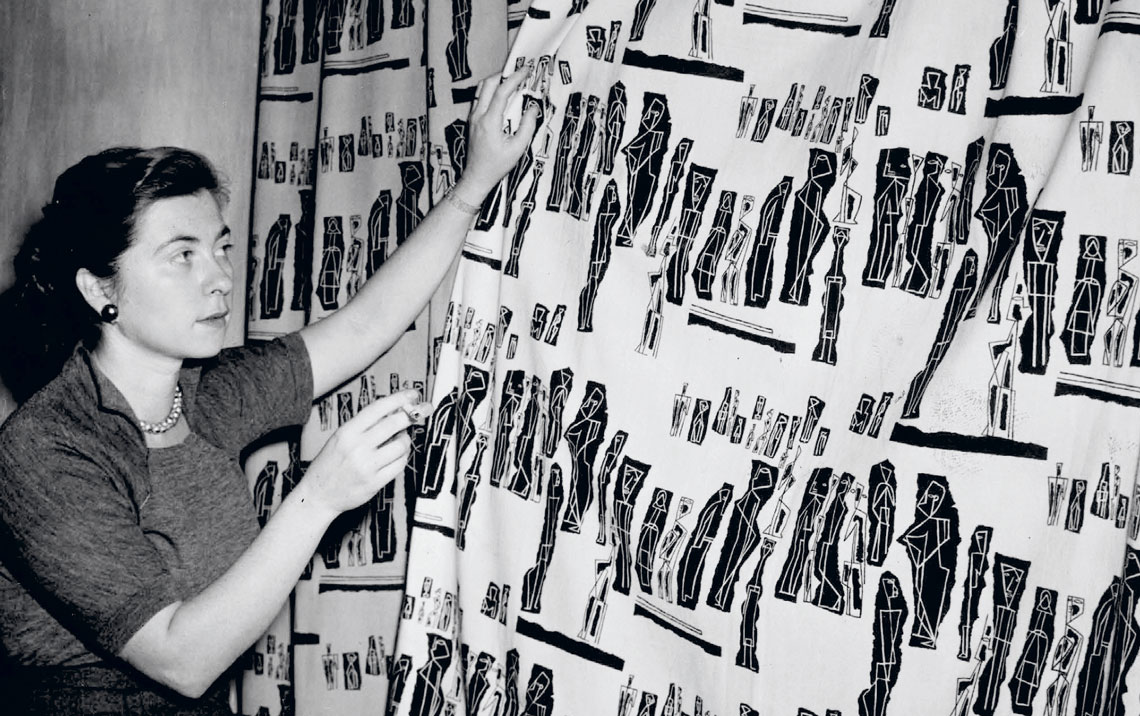

Peter Scheier ©Instituto Moreira Salles / MASP Research Center CollectionKlara Hartoch (in the back) with a student in the weaving workshop located at MASP in the early 1950sPeter Scheier ©Instituto Moreira Salles / MASP Research Center Collection

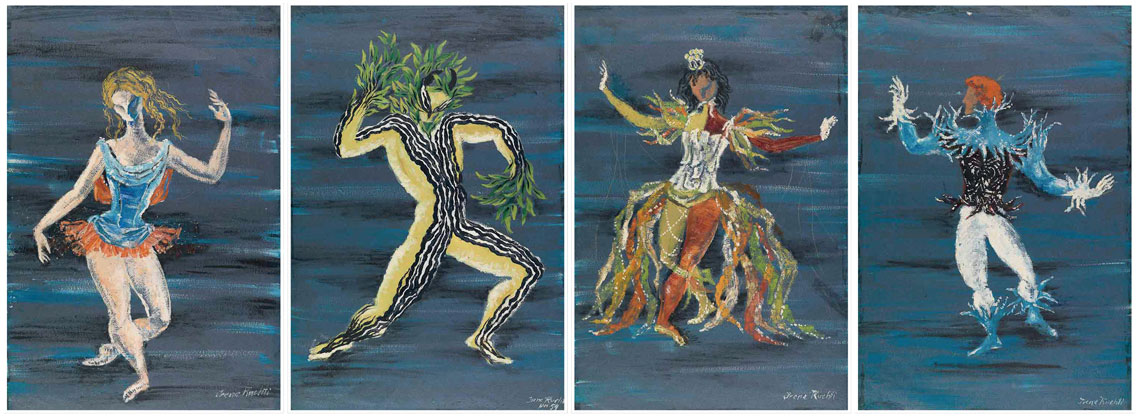

In the 1950s, a series of initiatives commemorated São Paulo’s 400th anniversary, celebrated in 1954. One such initiative was the formation of the IV Centenary Ballet Dance Company, which produced a special repertoire of choreographies and hosted several performances. At just 21 years old, Irene Ruchti (1931–2020), a student in the first graduating class at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the São Paulo Museum of Art (IAC-MASP), created by Pietro Maria Bardi (1900–1999) and Lina Bo Bardi (1914–1992), was invited to join the team of artists commissioned to design the sets and costumes for the plays. Responsible for imagery in As quatro estações (The four seasons), she tackled the same responsibilities attributed to well-known artists such as Lasar Segall (1889–1957) and Candido Portinari (1903–1962) — who are, commonly, the names mentioned in articles about such shows.

Although awarded for her work by the Museum of Fine Arts in Rio de Janeiro, Ruchti said she was never formally notified. And, although her creations were featured on the cover of an edition of São Paulo’s Jornal da Noite regarding the award, the article focused on Segall’s participation. “I was there, smack dab in the middle, the most unsung, the youngest, and the most insignificant among the greats,” she said in an interview with Ana Julia Melo Almeida, author of the doctoral dissertation “Mulheres e profissionalização no design: Trajetórias e artefatos têxteis nos museus-escola MASP e MAM Rio” (Women and professionalism in design: Trajectories and textile artifacts in the MASP and MAM Rio museum schools).

The dissertation, defended in 2022 at the University of São Paulo’s School of Architecture and Urbanism (FAU-USP), retraces the trajectory of not only Ruchti but also four other women who worked in textile design and attended the two museum schools mentioned in the dissertation’s title: Klara Hartoch (1901–?) and Luisa Sambonet (1921–2010), also linked to IAC-MASP, as well as Fayga Ostrower (1920–2001) and Olly Reinheimer (1914–1986), linked to the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro (MAM). Marta Erps-Breuer (1902–1977), a former student at Bauhaus, a famous German school for architecture, design, and visual arts, rounds out the group analyzed by Almeida (see sidebar).

Correio da Manhã Newspaper / National Archive CollectionFayga Ostrower showcasing one of the fabrics she exhibited in a solo show at the MAM in Rio de Janeiro in 1953Correio da Manhã Newspaper / National Archive Collection

With a degree in design from the Federal University of Ceará (UFC), Almeida sought to understand the role that women play in this phase of Brazilian design and the place occupied by textile objects in the historiography of this field of knowledge in Brazil. According to the researcher, pieces produced by these women and others have mostly fallen into obscurity. This is because, although modern design has come to view weaving, sewing, and embroidery (once classified as household tasks or, at best, menial labor) as artistic expressions, this does not mean that their automatic association with feminine and less refined work is a thing of the past.

Historian Silvana Rubino, of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), looks back even further: “The devaluation of textiles in art dates back to the Arts and Crafts movement in nineteenth-century England. England’s greatest mentor, William Morris [1834–1896], delegated embroidery to women, although he himself was an expert embroiderer,” she recalls. A few decades later, Bauhaus (1919–1933), seen as pedagogically revolutionary, was no different in this respect. “The female students were sent directly to the weaving workshop,” adds Rubino, who delved into the subject in her doctoral dissertation “Lugar de mulher: Arquitetura e design modernos, gênero e domesticidade” (A woman’s place: Modern architecture and design, gender, and domesticity; 2017).

According to Ana Paula Cavalcanti Simioni, a professor at the University of São Paulo’s Brazilian Studies Institute (IEB-USP), the association between textile work and women is still very much alive and kicking. For this reason, “some male artists who use embroidery end up being seen as transgressors, such as Leonilson [1957–1993], who, through these techniques, even prompted important questions about standard views of masculinity, which permeate, however subtly, the art world,” observes the scholar, whose habilitation thesis resulted in the book Mulheres modernistas: Estratégias de consagração na arte brasileira (Modern women: Strategies for consecration in Brazilian art; Edusp, 2022), published with the support of FAPESP (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 311).

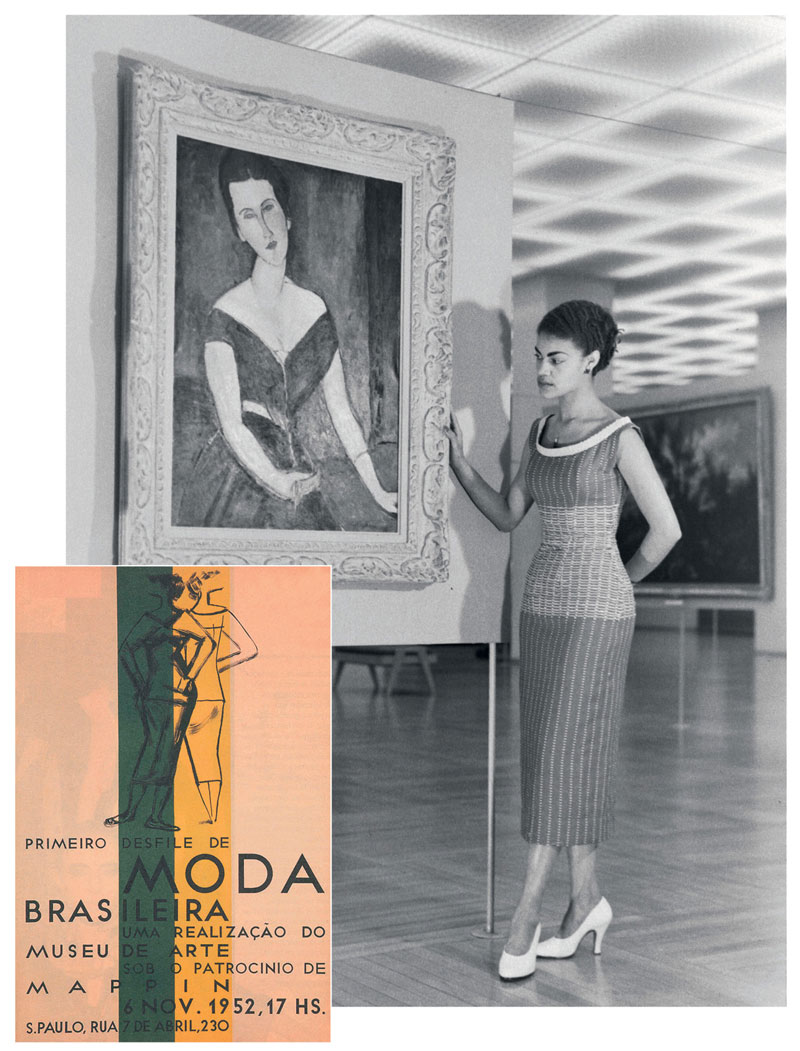

Peter Scheier ©Instituto Moreira Salles / MASP Research Center CollectionThe Balaio dress, created by Hartoch for the First Brazilian Fashion Show (1952), at MASP; the event announcementPeter Scheier ©Instituto Moreira Salles / MASP Research Center Collection

In the book, Simioni outlines the biography of Regina Gomide Graz (1897–1973). The textile artist lived with her family in Switzerland and attended the Geneva School of Fine Arts — which, contrary to the happenings in England, France, and Germany, valued the applied arts and trained prestigious decorative artists. With this background and the professional partnership established with her husband, John Graz (1891–1980), also a student at the Geneva School of Fine Arts, she returned to Brazil in the 1920s. “Regina paved the way for this field of work in Brazil,” says Simioni. “In dividing the tasks with John, who was credited for the entire project, she handled the textiles, which, because they were less valued, meant that she was not seen as the author, but as her husband’s assistant.”

However, none of this prevented the textile artist from opening her own rug factory in the 1940s, bearing her first name. “No Gomide, for her famous brother [the modernist artist Antonio Gomide (1895–1967)], and no Graz,” Simioni continues. “With this approach, she ensured her work was autonomous.”

In 1951, a school emerged in São Paulo that was dedicated to training professionals for the embryonic Brazilian furniture and design industry: the IAC-MASP. The following year, a similar initiative took shape at MAM in Rio de Janeiro. Precursors of formal education in the field — the School of Industrial Design (ESDI) in Rio de Janeiro was only founded in 1962 — “both spaces were already discussing industrial design as a profession and seeking to understand the relationship between the arts and applied arts,” says Almeida.

The only Brazilian among the six women profiled by Almeida, Ruchti, from Santa Catarina, studied fine arts at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). In 1951, she joined the first class of industrial design at IAC-MASP and, the following year, she married architect Jacob Ruchti (1917–1974), her composition teacher. With the exception of her commissioned work for the IV Centenary Ballet, she always worked alongside her husband. She reviewed the decor and interior designs proposed by Jacob — the drawings were identified with both of their initials.

Funarte Rio de Janeiro CollectionCostumes from As quatro estações ballet (1954), signed by Irene RuchtiFunarte Rio de Janeiro Collection

At Estúdio Branco & Preto, a São Paulo furniture and modern design store opened in 1952 and co-owned by Jacob, Irene’s presence has left but a shadow. Although the artist herself said that she designed most of the fabrics that upholstered the furniture, the researcher only found two records of her authorship. “This absence, in the case of furniture items, is recurrent in products featuring textiles, not only in women’s work, but due to a prevailing view, at the time, of fabric as a secondary material, which surrounds the item but does not structure it,” Almeida writes in her paper.

The researcher recalls that Hartoch experienced a similar situation in Brazil, in her partnership with architect Galiano Ciampaglia (1908–2016), as well as Ostrower, in the prints for furniture by designer Joaquim Tenreiro (1906–1992). In the case of Sambonet, the discrepancies in authorship are due to two factors. Firstly, she was not an official teacher at IAC-MASP, although she had run a clothes and accessories making workshop for the First Brazilian Fashion Show, held at the museum in 1952. In addition, she worked alongside her husband, painter Roberto Sambonet (1922–1995), and other artists and designers.

Ruchti, on the other hand, worked on the landscaping alongside her husband, while he was responsible for the architectural design. After the death of her partner, she embraced her career as a landscape artist. “At this stage, her signature took on a life of its own, already detached from Jacob,” says Almeida, who carried out research in Germany, France, and Italy to follow the trajectories of the six women. “Their lives have been marked by migratory movements,” says the designer.

Such is the case of Fayga Ostrower. Born in Poland, she moved to Brazil in 1934. In the early 1950s, when MAM in Rio de Janeiro began offering free courses, she was hired to teach the composition and critical analysis workshop. She remained there until the 1970s. “Fayga became known in the late 1950s for her abstract prints, for which she was awarded at the São Paulo and Venice Biennials. However, she had been producing textiles since the beginning of that decade,” says Almeida. “There are just over 170 pieces of fabric by her in the Fayga Ostrower Institute’s collection [in Rio de Janeiro], but the artist’s body of work could easily reach 500 textile pattern samples.”

One of her students was Olly Reinheimer, who left Germany for Rio de Janeiro in 1936. In the 1950s, she began attending free classes at MAM. “The archive material and the documents that remain help us understand that most of her work was in fashion textiles. There are not many records of decorative items,” says anthropologist Patrícia Reinheimer, of the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ) and author of the book about her grandmother, Olly: Race, Class, and Gender in the Invention of Rustic Modernity (Common Ground Research Networks, 2021).

In the 1960s, the artist and designer exhibited at venues such as the Museum of Contemporary Crafts in New York, as well as taking part in the 1st Biennial of Applied Art in Uruguay. Today, her nearly 10,000 items, including personal objects, books, documents, and creations, are in the care of her granddaughter, in Petrópolis (Rio de Janeiro), who intends to exhibit the materials before looking for institutions to take over the collection. “Storing and maintaining such a large volume on my own is a huge challenge.” It is common for heirs to want to dispose of the estate quickly. Sometimes an artist’s lack of recognition comes from within her own family,” she concludes.

Trained in weaving at the Bauhaus school, Marta Erps-Breuer contributed to genetic studies at USP

Collection of the Genetics and Evolutionary Biology Department at IB-USPErps-Breuer at USP, in 1937Collection of the Genetics and Evolutionary Biology Department at IB-USP

In her doctoral dissertation, researcher Ana Julia Melo Almeida also investigated the career of German Marta Erps-Breuer (1902–1977), who had an unusual career: she was a close colleague of geneticists André Dreyfus (1897–1952) and Crodowaldo Pavan (1919–2009), at the University of São Paulo (USP).

In the 1920s, Erps-Breuer studied at the Bauhaus school. “Marta took part in a weaving workshop and attended sculpture, typography, and furniture workshops, and was exposed to photographic techniques,” says Almeida. “We see that despite the restrictions and focus on the weaving workshop, women moved around to other fields and acquired various skills.”

In 1931, she immigrated to Brazil after separating from designer Marcel Breuer (1902–1981), her contemporary at Bauhaus. In a letter to her colleague Kurt Schmidt, who also attended Bauhaus, she let off steam: “I decided I no longer wanted to be just the wife of a genius. I wanted […] to find myself.”

In São Paulo, she started working as a designer for two doctors. Shortly afterwards, in 1935, she went to work as a laboratory technician in the General Biology Department headed by Dreyfus at the newly created USP. Even though she had no training, she contributed to research in genetics and evolutionary biology. The first studies involving Erps-Breuer date back to the 1940s. They focused on insect species, such as the Telenomus fariai (wasp), and were coauthored with Dreyfus.

In 1955, she published an article with Pavan based on observations of a fly of the genus Rhynchosciara. In their work, the pair overturned the dogma that the amount of DNA in a cell was constant (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 283). As well as taking part in research projects, she was also responsible for documenting and detailing the studies through drawings, diagrams, sculptures, and photographs.

Despite the detour, she never lost sight of design. In 1938, she participated in the exhibition Bauhaus: 1919–1928, held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA). In the late 1960s, she submitted materials for the exhibition celebrating the institution’s 50th anniversary. Everything was rejected on the pretext that the curators had already chosen a tapestry by her. “But Marta said in a letter that the piece had not been woven by her, but by another colleague. This misattribution shows that there was a lack of knowledge of the work produced by the weaving group,” Almeida concludes.

Projects

1. Textile artifacts: Women and design in Brazil (nº 18/00487); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowships in Brazil; Supervisor Maria Cecilia Loschiavo dos Santos; Beneficiary Ana Julia Melo Almeida; Investment R$163,355.21.

2. Women, migration, and spaces for professionalization: Gender relations in modern design (nº 19/06880-9); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship Abroad; Supervisor Maria Cecilia Loschiavo dos Santos; Beneficiary Ana Julia Melo Almeida; Investment R$136,515.23.