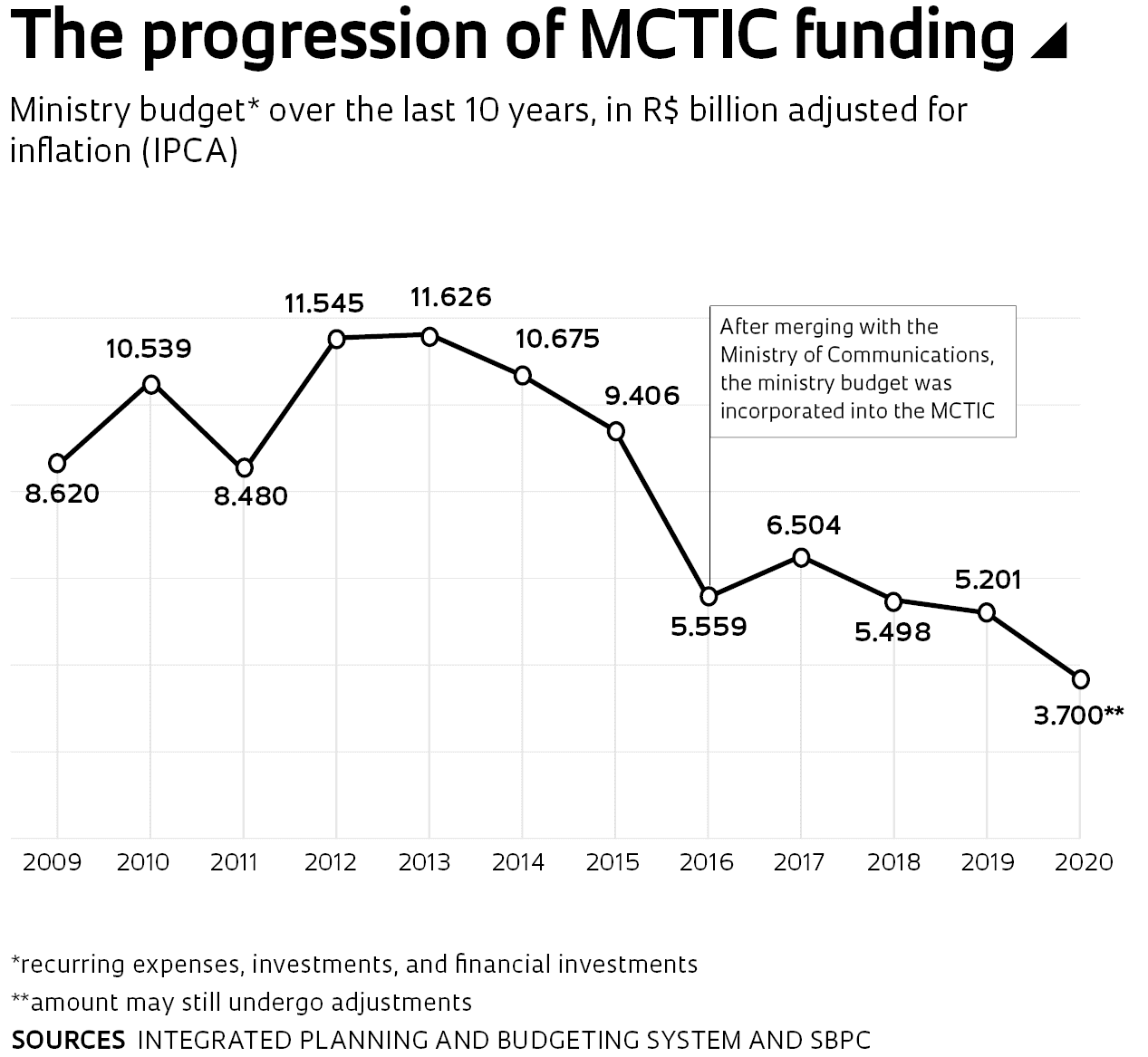

Brazilian researchers should rest easier in 2020 after the National Congress shielded the budget of the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communications (MCTIC) from new cuts. The move was sanctioned last December with the approval of the Lei Orçamentária Anual (Annual Budget Law) (LOA). The news was received with some relief by the scientific community, which experienced financial difficulties and uncertainty in 2019, after the government froze the MCTIC budget at 42% in March, forcing it to work with its lowest funding in more than a decade. At the time, the government also restricted 30% of the funding toward federal universities linked to the Ministry of Education (MEC). “This is an important victory, but we continue to be concerned about the budget, which remains very low,” says physicist Ildeu Moreira de Castro, president of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC).

The 2020 MCTIC budget will be R$11.8 billion. From that amount, R$5.1 billion is considered a contingency reserve and cannot be spent on science, technology, and innovation (ST&I). Instead, it will be used to reduce public debt. Another portion of the funding, nearly R$983 million, is described in the budget as supplementary credit subject to congressional approval before being used. After subtracting all of these amounts and any mandatory expenses, the net funding of the MCTIC will be approximately R$3.7 billion in 2020 (see chart). “The budget has been shielded by Congress from being further reduced in 2020, but it does not undo the cuts built into the bill itself,” explains Moreira. “The outlook for ST&I in 2020 remains bleak.”

Prospects are also grim for the top research development agencies in the country. The amount granted to the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) in 2020 was adjusted by 0.66% in relation to that of 2019. The Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) had its budget cut by 33.1% compared to the previous year (see table).

Funding for science is not restricted to the MCTIC, but is also included in the budget of other ministries, such as Health, Defense, and Education (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 256). To mitigate the damage, Congress members managed to approve an additional amendment, presented by Congressman João Campos (PSB-PE), extending the protection from more cuts to other federal institutions in the national ST&I system, such as the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA) and the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ). This amendment, however, was vetoed by President Jair Bolsonaro, on advice of the Ministry of Economic Development and the General Secretariat of the Presidency. “They argued that it would promote an inflexible budget, making it harder to implement other public policies,” explains Congressman Campos. “The vetoes will still be analyzed in the plenary of the Congress,” states Senator Izalci Lucas (PSDB-DF), one of the main advocates for the scientific community in Brasília. “What concerns us most at this moment is the situation of the FNDCT [National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development].” Managed by the Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP), the fund is the main support tool for MCTIC research projects, but it is currently going through a period of recession and uncertainty (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 285).

Campos shares Lucas’s concern about reducing funding for ST&I and is working with other congress members to overturn the veto to the amendment that prevents the budget cuts for institutions not controlled by the MCTIC. He claims the chances of that happening are high. “Congress members are adamant about the importance of funding for the sector,” he says. “Brazil cannot move in the opposite direction as the rest of the world in terms of funding for science and technology.”

The partial restoration of the funding for ST&I is the result of political talks that also involved representatives of institutions linked to the sector during discussions for the proposed budget law—the first in the current administration. One of the actors involved was the National Confederation of Industry (CNI), which has, for over a decade, been investing in the relationship between the public and private sectors through the Mobilization for Business Innovation (MEI) initiative. MEI brings together about 300 Brazilian business leaders and acts as a forum for dialogue with government, academia, and civil society (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 266). “MEI leaders meet every three months with representatives from government and academia to discuss possible means of driving innovation in the country,” explains Gianna Sagazio, director of Innovation at CNI and coordinator of MEI.

Sagazio believes one of the most decisive meetings to raise awareness among congress members about the need to secure funding for ST&I took place in November 2019 at the CNI headquarters in Brasília. The event was attended by authorities such as Rodrigo Maia (DEM-RJ) and Davi Alcolumbre (DEM-AP)—the presidents of the House of Representatives and of the Senate—and businessmen from various sectors of industry. “We discussed how innovation leads to development and the importance of a long-term policy based on goals and secured funding,” shares Sagazio.

The meeting was initiated by the CNI and the Mixed Parliamentary Committee for Science, Technology, Research and Innovation, created in July 2019. This initiative is comprised of 207 congress members from several different parties, who meet with members of the scientific community and civil society to discuss topics of interest to the sector. It is chaired by Izalci Lucas, who had already initiated talks for the creation of this same nonpartisan front in 2009, when he was still a deputy for the PFL, today called Democratas. Now a member of the Senate, he works toward expanding this group alongside Congressman Vitor Lippi (PSDB-SP), vice president of the committee.

According to Lucas, one of the results of the meeting at the CNI was an alignment between congressmen and senators from different parties around the strategic potential of ST&I for Brazil. This stance became clear in an article published last November in the newspaper O Globo. Signed by 22 party leaders from all parts of the political spectrum, the declaration, penned by Congressman Alessandro Molon (PSB-RJ), proposes restoring funding for research in order to overcome the current crisis. Another result is evident among the Joint Budget Committee. According to Lucas, “ST&I has never been so relevant on the agenda of the committee.”

CNI has also been communicating with other institutions, such as the National Association for Research and Development of Innovative Companies (ANPEI), to advance other agendas that can potentially boost innovation in the country. One of them concerns the Legal Framework for Startups and Innovative Entrepreneurship, a critical tool to leverage innovation in Brazil, according to Sagazio. “Startups are essential for job creation and for boosting the economy in many countries,” she says. “We need to improve the regulatory system for these small innovative companies in Brazil.” Last December, the House of Representatives created a commission for the assessment of the legal framework bill, put together and presented by the government. In February, the commission approved a work plan for public hearings with experts from the private and public sectors, including Minister Marcos Pontes, of the MCTIC, to take place between March and April. “MEI has been promoting meetings with Congress members to discuss suggestions for the wording of the new law, such as the creation of a tool similar to the ‘Lei do Bem’ [a set of tax incentives for R&D to boost innovation]”, adds Sagazio. This Legal Framework is expected to be approved by Congress this year.

One of the challenges faced by the scientific community in 2019 was to identify new friendly ears in Congress and initiate a conversation with them. The House came out of recess in February 2019 with 47% new members—the highest number since the 1998 election. In the Senate, that rate was 85%. This means that several Congress members are newbies, while others, sympathetic to the interests of the scientific community, have failed to get reelected. Some entities in the sector have been monitoring candidates aligned with the defense of ST&I since their electoral campaigns began, as preparation for networking in Congress. Such is the case with SBPC, which approached presidential candidates, and candidates for the Senate, House of Representatives, and Legislative Assemblies during their campaigns, and asked them to sign a document including a list of commitments to ST&I, in case they were elected. Last May, the entity also launched the Science and Technology in Parliament Initiative (ICTP.br), partnered with the Brazilian Academy of Science (ABC) and 60 other academic institutions.

Moreira, from SBPC, explains that the initiative aims to promote better communication with Congress members, so they can present to them the demands of the sector. They include the approval of bills that have been “frozen” in Congress, such as PLS No. 315/2017, which proposes to turn the FNDCT into a financial fund—thus generating interest even from contingency funds that could then be used by the MCTIC—and Bill No. 5,876/2016, which proposes to allocate 20% of the Pre-Salt Social Fund to scientific and innovation programs. They also call for the overturning of presidential vetoes to the Equity Funds Law, sanctioned in 2019, which secures a legal framework for research institutions with funding difficulties to raise private funds.

Another strategy used by SBPC to approach Congress members involves seeking their support based on matters that are of interest to them specifically. “We try to show them how the approval of bills of interest to ST&I can contribute to the progress of bills that benefit sectors of interest to them,” explains Mariana Mazza, parliamentary advisor at SBPC. This was how they obtained support from the leadership of the Solidariedade party for Bill No. 5.876/2016, pending with the Science, Technology and Innovation Commission of the House, and which proposes to allocate 20% of income from the Pre-Salt Social Fund to ST&I. “Support for this bill came once they understood that it can set a precedent for a similar bill, also allocating pre-salt resources, but toward public security.”

These moves by the ICTP.br are part of a strategy initiated by the SBPC itself in 2011 to strengthen communications with Congress. According to biochemist Helena Nader, from the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP)—a former president of the SBPC—the institution decided at the time to hire a parliamentary advisor. “Biologist Beatriz de Bulhões [1965–2016], chosen by the SBPC for this position, did a great job promoting dialogue with members of Congress,” says Nader. “Our strategy was simple. We approached the leaders and presented our ideas and demands, systematically monitoring and critiquing bills of interest to us.”

A decisive point in the strategy adopted by the SBPC at the time was to seek out Congress members from all parties and ideological orientations in an effort to create a policy focused on strengthening the national ST&I system. “We knocked on all of their doors explaining the demands of the scientific community,” shares the researcher, who led the SBPC between 2011 and 2017.

According to Nader, this effort contributed to mobilizing businessmen and public administrators around agendas that later culminated in several legal changes for scientific activities in the country—known as the Legal Framework of ST&I, approved in 2016. She believes the challenges posed by the current administration reinforce the need for better communication with Congress members from different political backgrounds. “Minister Pontes is open to dialogue, but we know that there is little he can do, given the economic agenda imposed by the administration.”

The action of members of the European Parliament and that of state members of the European Union secured the approval of a €100-billion budget for Horizon Europe, a program to drive scientific research and innovation expected to run from 2021 to 2027. This amount is 23% higher than the budget of the program’s predecessor, Horizon 2020, which will come to an end later this year.

The budget was approved at a troubled time for Europe, with the United Kingdom in the process of leaving the European Union. However, the amount is still considered insufficient to solve the main challenges faced by Europe. It is estimated that, adjusted for inflation, the increase in the budget of Horizon Europe compared to Horizon 2020 is less than €10 billion. In light of this, several organizations that represent the European scientific community, including the European Consortium of Innovative Universities and the European University Association, are negotiating with politicians to secure a budget of at least €120 billion.