In July, prosecutor Luiz Gustavo da Luz Quadros is expected to begin coordinating a unit of the Department of Agrarian Justice of the Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP) of Pará. The special unit is being created in the municipality of Castanhal, near the state capital, to mediate the resolution of property conflicts with the aid of new technological resources. “We want to avoid problems being resolved with violence, or at gunpoint, and having national and international repercussions,” Quadros says. In 2017, the state of Pará reported 71 rural workers were killed due to land conflicts, with 24 such deaths recorded in 2018. As of March 2019, six other murders have been associated with land disputes. Quadros intends to recognize the legitimate owners and regularize the state’s land situation whenever possible through friendly agreements, without judicial processes, using the Land Geographic Information System (SIG-F), a computer platform developed by a multidisciplinary team from the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), in collaboration with the MP and the Judicial Court of the State of Pará.

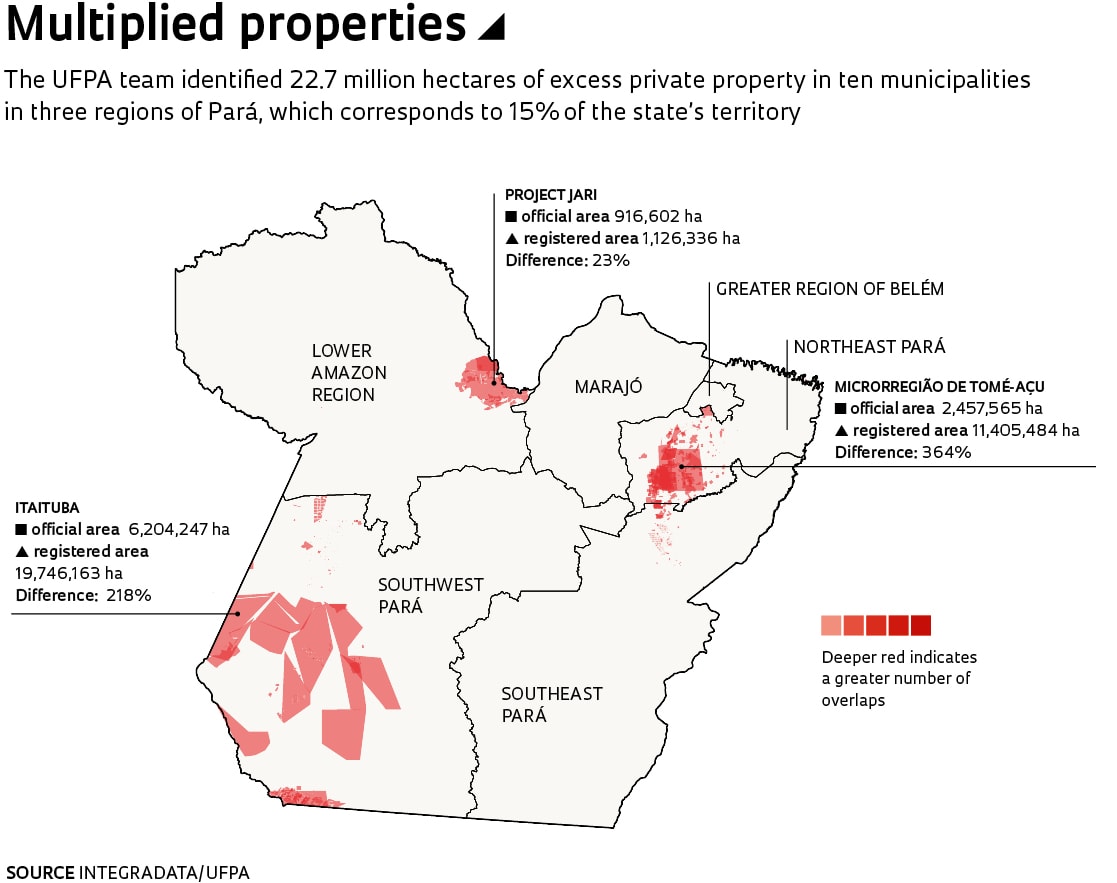

The SIG-F platform has done something completely original by integrating the databases of public agencies and notary registries, and describing the actual land ownership situation throughout the state. Preliminary results revealed 22.7 million hectares of private land and 18.5 million hectares of public lands that do not actually exist, because the sum of the areas recorded in notary registries exceeds the total geographical area of the municipalities. Known as a matrícula [title deed], the document that allows the sale or donation of real estate generates a new registration record each time there is a change in ownership. The SIG-F system identified situations with up to ten concurrent records, as though there were ten owners or sets of owners, with overlapping areas.

Created five years ago, with funding of about US$1.6 million from the Ford Foundation and the NGO Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA), the SIG-F system collected 83,676 documents from three regions within Pará—Tomé-Açu, Jari, and Itaituba—which add up to 19.5 million hectares, equivalent to 15% of the state. The team from the Laboratory for the Integration of Agricultural, Economic, and Environmental Information for Dynamic Analysis of the Amazon (INTEGRADATA), which is the agency of the UFPA Dean’s Office responsible for SIG-F, collected information directly from the registrations and records of 14 of the state’s 104 notary offices. The work of digitizing documents at the notary registry of Santarém began in February. At INTEGRADATA the documents are verified, historical data are indexed, and the geographical location coordinates of the properties are inserted in a geographic information system. Open-access programs allow the recording of information, document integration, and automatic map production. In 2018, at the request of the state government of Maranhão, the INTEGRADATA team used this method to register 23,616 documents from the Colonization and Lands Institute of Maranhão (ITERMA), and two state notary registries.

Overlaps

The area of properties recorded in the registry documents at the ten municipalities surveyed in Pará totaled 32.2 million hectares. As the area studied has only 9.5 million hectares, 22.7 million of these hectares do not actually exist. “They are paper lands,” says agronomist Sebastião Aluizio Solyno Sobrinho, technical coordinator of SIG-F. In another study, the INTEGRADATA team gathered together the maps of protected areas, indigenous lands, and quilombolas [areas settled by escaped slaves] under the jurisdiction of federal public agencies in Pará, and found 792 property overlaps totaling 1.5 million hectares. According to the official documents, the total area of indigenous lands and conservation units is 8.4 million hectares larger than that identified by the SIG-F system. As for public lands, there are 18.5 million hectares that don’t actually exist. “Over recent years, the maps have been corrected on the institutional websites of the federal government agencies, but the erroneous information remains on the official documents,” notes Solyno.

In his view, the overlaps detected by the SIG-F platform can result from both technical inaccuracies and illegal land possession. “We have to analyze each case carefully, identify the most serious situations, and then construct an appropriate work methodology.” The Ministry of the Environment estimates that the total area of lands obtained through false titles in Pará, as recorded in real estate notary registries, comes to 30 million hectares, almost 25% of the state’s land surface.

Fernando Santos / Folhapress

Police officers go to the countryside to contain land conflicts between squatters and farmers in Pará in August 1984Fernando Santos / FolhapressThe overlaps were rarely apparent to the extent now detected by SIG-F because the public databases are rarely integrated, and the staffs at public agencies prioritize more urgent problems. Geographer Danny Silvério Ferreira Sousa, a technician from the Land Institute of Pará (ITERPA), a public agency responsible for land management throughout the state, notes that 6,126 land regularization suits have been filed at the institute’s Cartography and Geoprocessing Administration as of November 2018, an average of 875 cases for each of the seven employees in the division.

The Rural Environmental Registry (CAR), created by the federal government in 2012 to facilitate the regularization of the mandated environmental preservation areas throughout Brazil, recorded an excess of private property in Pará of 12.1 million hectares, of which 1.1 million hectares overlap indigenous lands. Because it receives information provided directly by the rural property owners, the CAR allows room for inaccuracies and fraud. In 2016, the Federal Revenue Service arrested a gang headed by a São Paulo businessman, who was clearcutting and filing fraudulent title records for public lands in the state. Registration with the CAR on behalf of various front companies allowed the land to be exploited, leased, and sold. According to a report from the investigative journalism site Agência Pública, the criminal organization moved R$1.9 billion and cleared about 300 square kilometers of forests between 2012 and 2015. The National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA), responsible for federal land management, has adopted a program similar to the CAR, the Land Management System (SIGEF), certifying land ownership only when no overlap exists.

“The notary registries are partially responsible for this situation, having recorded new title deeds without verifying previous documents,” observes José Antonio Cavalcante, an assistant administrative review judge at the Judicial Court of the Metropolitan Region of Belém. He believes that “due to ignorance of the duty of office or bad faith,” the notaries kept the initial records open, allowing the sale of land even when the area was under the jurisdiction of another notary office. “When we find irregularities,” says Cavalcante, “we have the notaries block further registration to prevent the land being passed on to third parties until the owners present their documents and resolve the problem.”

Anderson Barbosa / Folhapress

Besides the overlaps with private properties, the indigenous areas of Pará are subject to threats such as the construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric project in Vitória do XinguAnderson Barbosa / FolhapressUncertainties

In 2009, a commission instituted by the Judicial Court of Pará to combat fraudulent filings found that the 9,124 documented areas totaled about 490 million hectares, an area almost four times larger than the entire state. In Moju, in northeastern Pará, the irregularities corresponded to an area eight times that of the municipality itself. The commission requested that about 5,500 real estate titles covering more than 2,500 hectares be blocked, since the sale or concession of public lands above this limit depends on prior approval by the national Congress.

“Recognizing the mess is the first step to finding the appropriate legal methods to putting the state’s land management in order,” says attorney Girolamo Domenico Treccani, who coordinated the commission’s establishment, then as chief legal advisor for ITERPA. Currently coordinator of institutional analyses for SIG-F and a professor at UFPA’s Institute of Legal Sciences, he notes that one of the damaging consequences of fraudulent title registration is the expulsion of traditional communities, such as the indigenous and quilombola peoples. “Ambiguity is the basis of power, corruption, and the illegal sale of land,” says economist Francisco de Assis Costa, from the UFPA Center for Advanced Amazon Studies (NAEA), and the general coordinator of SIG-F. “Doubts regarding land ownership result in societal insecurity and reduced economic opportunities,” he wrote in the book Questões agrárias, agrícolas e rurais [Agrarian, agricultural, and rural issues] (E-Papers Publishing, 2017).

The situations aren’t always easy to resolve. One of the cases brought forward by SIG-F began in 1960, at the request of a farmer interested in acquiring, from the state government, an area in Marabá of about 3,000 hectares, occupied by a grove of chestnut trees. Because the area had been earmarked for natural resource extraction, the request was denied. A short time later, however, making use of a legal instrument similar to a fee farm grant, the state transferred the land to the farmer. Over the next 40 years the area was bought and resold several times, without definitive title of ownership. One of the buyers registered it in 2004, in Itupiranga, an incorporated municipality that had subdivided from Marabá. Six years later, ITERPA granted the current owner, a resident of Minas Gerais, a clear title, which was then canceled in 2014 because the area exceeded the limit of 2,500 hectares.

In the disputes over legal possession of rural properties there remains one certainty: “Someone will lose,” says Patricia Moreira, an assistant administrative review judge for the rural district Judicial Courts of Pará. In November 2018, for example, the court blocked the ownership rights to two large farms in Acará, in northeastern Pará, under the allegation that the properties—which had been public lands—had been wrongfully occupied and that the company that claimed ownership had presented false documents when registering them at the notary office. “There will be protests over the regularizing work that’s being done,” the judge commented, “but also greater legal certainty, because legalized land will be more valuable.” At the beginning of April, she listened with interest to the UPFA team present the SIG-F system, recognizing its potential to ameliorate the land conflicts in Pará.

Software program indicates possible areas for legal compensation forests in the state of São Paulo

In February 2019 the Brazilian Rural Society in São Paulo met with agronomist Gerd Sparovek, president of the São Paulo Forest Foundation and a professor at the Luiz de Queiroz School of Agriculture, at the University of São Paulo (ESALQ-USP). He presented to the group of 100 farmers, lawyers, and representatives from government agencies and NGOs the latest version of a computer program that indicates possible areas for legal reserve compensation in the state of São Paulo. According to the new Forestry Code, in effect since 2012, all rural property within the state must maintain 20% of its area with native vegetation. This value corresponds to the legal reserve area combined with the permanent preservation areas; property owners with less than the 20% reserve can restore native vegetation or provide compensation in another location. Open to any interested party, for now the program (bit.ly/compRL_SP) only contains data from the state of São Paulo. Within the state, 30,417 rural properties have an accumulated legal reserve deficit of 865,391 hectares.

“As soon as the Federal Supreme Court publishes its Forest Code ruling, which was handed down on February 28, 2018, the program will allow us to objectively evaluate possible definitions of ecological similarity for legal reserve compensation,” says Sparovek. To comply with the new legislation, property owners with legal reserve deficits have four options: to restore their own forests; to lease an area on another property; to buy a forested area within a fully protected conservation area and donate it to the state; or to acquire surplus areas of native vegetation, known as environmental reserve quotas, within the same state and featuring the same biome.

Sparovek presented a set of maps showing possible legal reserve compensation scenarios in accordance with Article 68 of the Forest Code, which allows for the adaptation of preservation areas to previous laws. “If the owner has less than 20% of native vegetation on his property, Article 68 exempts them from the reserve percentage of the current law if the property is in accordance with the environmental legislation from the time in which the native vegetation was converted into other uses,” explains

biologist Paulo André Tavares, researcher at the Esalq group. The legal framework of 1934 established the obligation to maintain 25% of the native vegetation on rural property, but just like the 1965 framework that followed it, did not specify the type of vegetation to be preserved. “We want to provide technical tools so the public manager can work securely and prevent improper or erroneous administrative behavior,” says Sparovek.

“We offer a number of possible legal reserve compensation scenarios to support decision-making by rural landowners or representatives of government agencies,” adds biologist Alice Brites, a postdoctoral fellow at ESALQ. Brites coordinated the six meetings held since 2017 with landowners, government representatives, lawyers, prosecutors, and other agricultural experts. The project is the result of deliberations initiated in 2015 regarding the implementation of the Environmental Regularization Program (PRA) with researchers from the Research Program on Biodiversity (BIOTA-FAPESP).

Project

Priority Areas for Legal Reserve Compensation: A study to develop a tool to aid decision-making and transparency in implementing the Environmental Regulation Program (PRA) in the state of São Paulo (nº 16/17680-2); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Program BIOTA; Principal Investigator Gerd Sparovek (USP); Investment R$1,147,138.91.

Book

COSTA, F. de A. Dinâmica fundiária na Amazônia: Concorrência de trajetórias, incertezas e mercado de terras. In: MALUF, R. S. and FLEXOR, G. (Eds.) Questões agrárias, agrícolas e rurais: Conjunturas e políticas públicas. Rio de Janeiro: E-Papers, 2017.