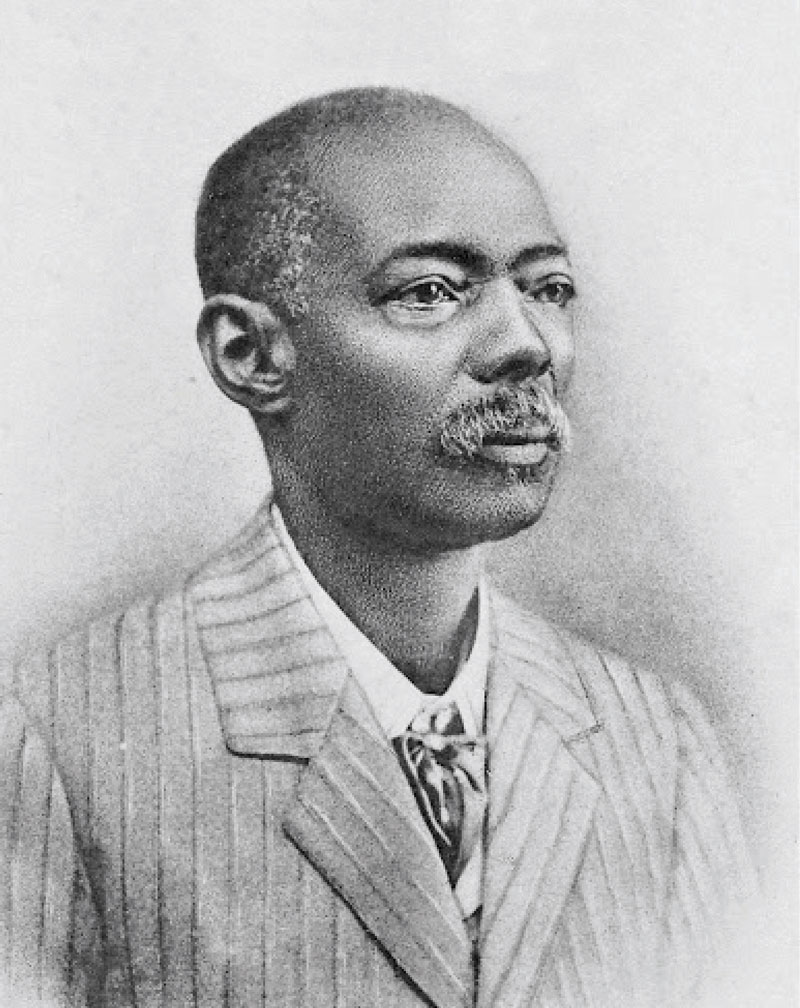

Wikimedia CommonsIn the preface of his book Artistas baianos (Bahian artists), published in 1911, Manuel Raymundo Querino wrote: “Bahia has a lot of preciousness in the dust of oblivion.” For a long time, memories of this Black artist, historian, ethnologist, writer, and politician, born free in 1851 — before the abolition of slavery — were also shrouded by this dust.

Wikimedia CommonsIn the preface of his book Artistas baianos (Bahian artists), published in 1911, Manuel Raymundo Querino wrote: “Bahia has a lot of preciousness in the dust of oblivion.” For a long time, memories of this Black artist, historian, ethnologist, writer, and politician, born free in 1851 — before the abolition of slavery — were also shrouded by this dust.

Querino enjoyed surprising prestige in a society where racist ideologies prevailed: his death, in 1923, was reported by various newspapers, and his funeral was attended by politicians and representatives from the Bahia Geographical and Historical Institute and the School of Fine Arts. But over time, his reputation faded into oblivion. A pioneer in several branches of knowledge, he began to be labeled as self-taught. “At the time, this would have been like saying he was illiterate. His books began being called opuscula,” recounts English historian Sabrina Gledhill, still indignant at the indifference more than 40 years after she began studying this historical figure.

The Black colonist as a factor of Brazilian civilization

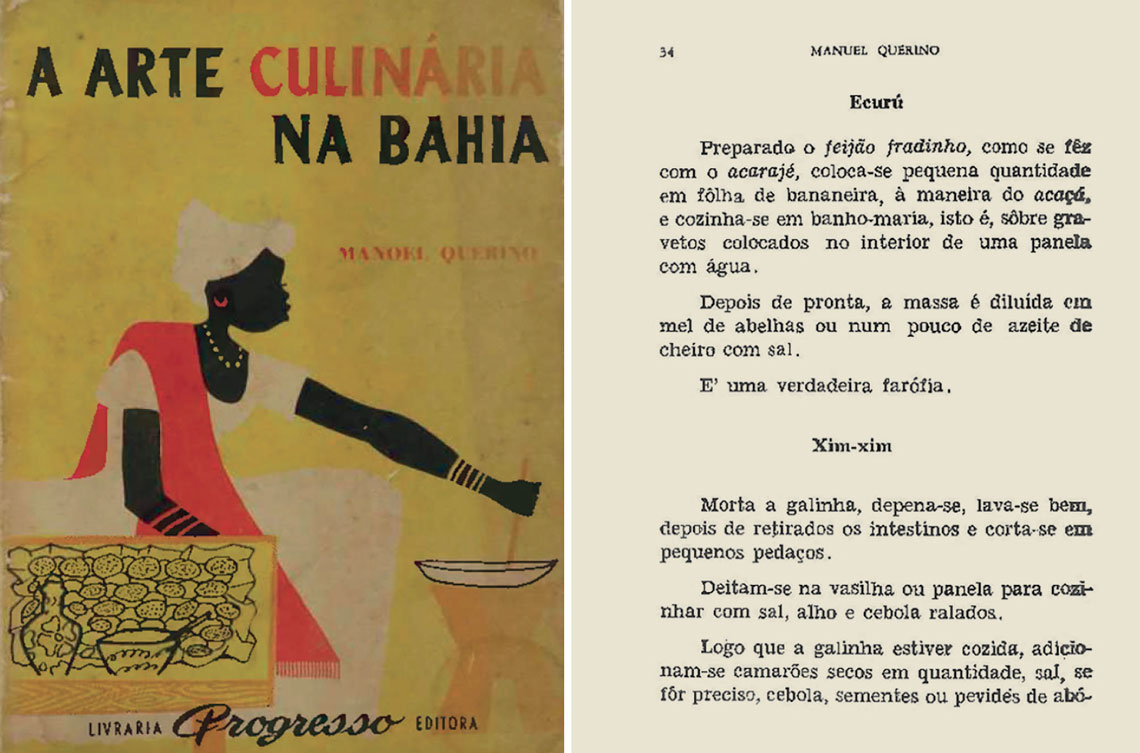

Today, academia recognizes Querino as the first art historian in Brazil and a pioneer of studying art history in Brazil. Author of one of the first books on Bahian cuisine, he helped create, as a founding student, the Lyceum of Arts and Crafts of Bahia and the School of Fine Arts, and he created two newspapers (A Província, in 1887, and O Trabalho, in 1892). He was one of the founders of the Bahian Workers’ League (1876) and the Workers’ Party (1890), and he was a counselor of the Salvador Municipal Council.

His most remarkable contribution, as unanimously identified by researchers, are the texts in which he highlights how Africans and their descendants played a leading role in forming Brazilian society. “He rejected the idea that the enslaved were passive laborers, detailing the knowledge brought from Africa, including mining knowledge. Until then, no Afro-Brazilian had expressed their thoughts on Brazil’s history,” states Gledhill.

QUERINO, M. A arte culinária na Bahia. 1957A book from 1957 with descriptions of traditional foodQUERINO, M. A arte culinária na Bahia. 1957

Prior to Querino, only two intellectuals of European descent — Rio de Janeiro-born lawyer Alberto Torres (1865–1917) and Sergipe-born doctor Manoel Bonfim (1868–1932) — had challenged theories such as “scientific racism” and “social Darwinism.” These pseudosciences postulated European seniority on an evolutionary scale and condemned interracial relationships, claiming that racial mixing caused physical and intellectual degeneration.

It was in this context that Manuel Querino published the book O colono preto como fator da civilização brasileira (The Black colonist as a factor of Brazilian civilization), in 1918, in which he stated: “Brazil owns two real treasures: the fertility of its soil and the abilities of its mulattos.” It was thanks to this phrase that Gledhill discovered Querino in the 1980s. She was looking for a topic for her master’s thesis in Latin American studies at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), in the United States. “I was reading Tent of Miracles, by Jorge Amado [1912–2001], in English, and I came across this quote by Querino as the book’s epigraph. I wanted to know who he was and reached out to my advisor [North American historian Edward Bradford Burns].” Burns (1933–1995) knew the figure well; he was the first foreign researcher to study the life and work of Manuel Querino, back in the 1970s. Gledhill had found her research topic.

Arriving in Brazil, now in search of a topic for her doctoral dissertation, Gledhill met Jorge Amado in person: “He confirmed for me that Querino was one of the inspirations behind the character Pedro Archanjo, from Tent of Miracles.” In the book, released in 1969, Archanjo is a mulatto researcher whose main adversary is the professor Nilo Argolo, a proponent of white supremacy — inspired by anthropologist and doctor Raimundo Nina Rodrigues (1862–1906), one of the first to address African influence on Brazilian culture and a Brazilian exponent of the eugenics movement, which preached against racial mixing.

Renata Nascimento / flickrCapoeira, one of the Afro-Brazilian cultural expressions that Querino valuedRenata Nascimento / flickr

“Jorge Amado portrays Pedro Archanjo as a multifaceted person, as was Manuel Querino. He wasn’t singular, but nuanced,” says historian Maria das Graças de Andrade Leal, from the State University of Bahia (UNEB) and author of a comprehensive biographical study on the Bahian who moved through different social spheres as a worker and intellectual, a supporter of candomblé and capoeira. “Through his life, the lives of many other Afro-descendants could be brought to light, allowing a version of history from the perspective of the oppressed.”

Born in Santo Amaro da Purificação on July 28, 1851, Querino was orphaned at the age of four when his mother and father fell victim to the cholera epidemic. According to Leal’s research, a neighbor took him in but, unable to keep him, asked the foster care system for help, a common practice at the time. The judge sent young Querino to professor, journalist, and politician Manoel Correia Garcia (1815–1890), appointing him as guardian. “During the cholera epidemic, there was a movement among certain elites in Bahia to provide guardianship for orphans, of which there were many,” she says. The boy did not live with his guardian, but he did pay for his studies—which certainly helped shape his story.

“His studies saved his life,” says Gledhill. At the age of 17, Querino was drafted into the Paraguayan War (1864–1870). He was in Piauí at the time — apparently fleeing the forced conscription to which poor free men were subjected. He managed to avoid being on the front lines, likely because he was one of the few soldiers who could read and write. He served as a clerk in Rio de Janeiro and, at the end of the war, returned to Salvador.

QUERINO, M. R. Artistas baianos. 1911 | Juliana Bruder / ipatrimônioChurch of Our Lady of the Rosary of Black Men, in Ouro Preto (MG), built by a brotherhood that defended the religiosity of Black peopleQUERINO, M. R. Artistas baianos. 1911 | Juliana Bruder / ipatrimônio

Querino worked as a painter and decorator during the day and studied at night. He studied humanities at the Lyceum of Arts and Crafts of Bahia and drawing at the Academy of Fine Arts. At the Academy, which would be renamed the School of Fine Arts during the Republican period, he received his drawing diploma in 1882. He went on to study architecture but was unable to complete his studies due to a lack of professors for the last two subjects he needed to graduate. Nevertheless, his first academic work was published in the local press: the project “Models of schoolhouses adapted to Brazil’s climate,” drawn up in 1883 for the Pedagogical Congress in Rio de Janeiro.

Querino began his political career in the labor movement. According to museologist and art historian Luiz Alberto Ribeiro Freire, from the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), his contact with the intellectual milieu did not lead him to reject his origins and expressions of popular culture. Popular practices such as samba, candomblé, and capoeira, which had been suppressed by the government in an effort to whitewash and civilize society, were valued in his writings. “In general, there was a kind of acculturation when people from the lower classes came to elite institutions; they acquired the hegemonic ideology. But Querino never stopped positioning himself in society as a working-class artist,” says Freire. In 1874, at the age of 23, he was one of the founders of the Bahia Workers’ League.

After graduating, he taught industrial design at the Lyceum of Arts and Crafts and worked as a painter and decorator. As he himself describes in the book Artistas Baianos — Indicações biográficas (Bahian artists — Biographical information), his work included painting public and private houses, streetcars, and the Santa Casa de Misericórdia hospital. He was an assistant to the Spanish painter Miguel Navarro y Cañizares (1834–1913), who was responsible for painting the backdrop of the São João National Theater. Freire explains that the painter and decorator painted artistic murals on walls, and no record of these works has been preserved. The painted curtain covering the theater’s stage burned in a fire that destroyed the São João National Theater in 1923.

col. Siemens-Museum, MünchenTo support himself, Querino painted streetcars and housescol. Siemens-Museum, München

The Bahian intellectual’s greatest legacy, therefore, lies in his studies on the history, culture, and folklore of Bahia and the African people. “Nina Rodrigues and Manuel Querino were considered by their contemporaries to be the greatest authorities on Afro-Bahian culture,” says Gledhill. While Rodrigues continued to be remembered and revered, Querino began to be belittled and patronized by academia. The physician and ethnologist Artur Ramos (1903–1949) classified him as an “honest researcher, a tireless worker,” but “without the methodological rigor and scientific erudition of Nina Rodrigues.” According to the researcher, racism and class prejudice are responsible for this view.

Freire believes that this reclamation has been made possible by the ability of Afro-descendants to more easily access university courses, especially since the 2000s. Since 2014, he has been coordinating a project that continues the work of Bahia’s first art historian: the Manuel Querino Dictionary of Art in Bahia. The electronic dictionary was created by a group of researchers from UFBA and the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia (UFRB), with the support of the Bahia State Research Foundation (FAPESB). It contains 362 entries on artists who were born or worked in Bahia, as well as information on movements and artistic heritage in the state. “The dictionary’s greatest achievement was to honor Manuel Querino’s memory by carrying on his work,” says Freire, who already has a new project in mind and is just waiting to retire from teaching in two years’ time. “My idea is to publish a Querino Collection, which will include all of his books and books written about him.”

In the audiovisual field, Querino also has heirs. In 2023, on the centenary of his death, the documentary Querino – 100 anos (Querino – 100 years) was released on YouTube. The film is an independent production, funded through the collective fundraising website Catarse. It was directed by Isis Gledhill, who inherited her passion for the story of her fellow countryman from her mother, Sabrina. Isis was born and raised in Salvador, a city that was not only the setting for her research but also Sabrina’s home for the last 28 years.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPPopular practices such as samba (left) and candomblé were repressed by the government, interested in whitewashing the populationLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

With the same goal of including Black people as protagonists in history, the Querino Project was launched in August 2022. It features a series of podcasts created by journalist Tiago Rogero and was developed by a team of 40 people. Produced by Rádio Novelo, the eight-episode project was written up by Piauí magazine and was one of the winners of the 2023 Vladimir Herzog Journalism Prize, in the Audio Journalism Production category.

The initiative was inspired by the “1619 Project,” by American journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, which rewrites the history of the United States based on the consequences of slavery: 1619 is the year in which the first enslaved people arrived in the United States. When Rogero and the team learned about Querino’s story — portrayed in episode 4, in which the right to education is discussed — they found the ideal name for the Brazilian project. “It symbolizes a lot of what we were trying to do in different aspects, telling the story of Brazil from an Afro-centric perspective, something we were already doing at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century,” says the journalist.

And new projects influenced by the multifaceted intellectual are in the works. In partnership with the Itaú Social Foundation and the Center for the Study of Labor Relations and Inequalities (CEERT), the content of the journalistic podcast is being adapted for use in the classroom, with suggestions for activities and further reading. Rogero has also written a book exploring the content of the podcast (due to be released in September by Editora Fósforo) and has already signed another contract to publish a fictional graphic novel. “It will be set in the ‘universe’ of the Querino Project, part of an effort to reach a younger audience as well,” says the author.

Scientific articles

GLEDHILL, Sabrina. Representações e respostas: Táticas no combate ao imaginário racialista no Brasil e nos Estados Unidos na virada do século XIX. Sankofa ‒ Revista de História da África e de Estudos da Diáspora Africana. São Paulo, Brasil, Vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 45–72, 2011.

Books

GLEDHILL, Sabrina (org.). (Re)apresentando Manuel Querino 1851-1923: Um pioneiro afrobrasileiro nos tempos do racismo científico. Editora Funmilayo, 2021.

GLEDHILL, Sabrina. Travessias no Atlântico negro: Reflexões sobre Booker T. Washington e Manuel R. Querino. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2020.

LEAL, M. G. A. “Manuel Querino: Entre letras e lutas Bahia 1851-1923.” Tese apresentada ao Programa de Estudos Pós-graduados em história da Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC-SP) para obtenção do título de doutor em história social, 2004. Published in 2009 by Annablume (out of print).

QUERINO, Manuel. A arte culinária na Bahia. Salvador: Progresso Editora, 1957.

QUERINO, Manuel. O colono preto como fator da civilização brasileira. São Paulo: Cadernos do Mundo Inteiro. 2 ed. 2018.

QUERINO, Manuel. Artistas bahianos. Indicações biographicas. Bahia: Officinas de Empreza. 2 ed. 1911.

QUERINO, Manuel. A raça africana e os seus costumes. Salvador: Livraria Progresso Editora. Coleção de Estudos Brasileiros, 1955.