The search for renewable energy sources is stimulating the global market for solid biofuel pellets and briquettes made from compacting different types of biomass, usually agricultural and forestry waste. Brazil, which already stands out for its production of liquid biofuels, such as ethanol and biodiesel, could be a leading player in this market if it can count on adequate public policies. This was the main conclusion of industrial engineer Diogo Aparecido Lopes Silva, professor at the Federal University of São Carlos (UFSCar), Sorocaba campus, upon studying these biofuels. Funded by FAPESP, the investigation was carried out from a Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) perspective, a technique that analyzes the potential environmental impacts associated with all the stages of the life cycle of a product, service, or process, from extraction of the raw material to the final disposal.

Pellets and briquettes are made from crushed, dried, and compacted plant biomass in cylindrical shapes, using high pressure equipment. A large variety of raw materials can be used in their production, such as pieces of wood, sawdust, peanut shells, cereal straw, sugarcane bagasse, and even urban waste, like pieces of tree trunks and branches from pruned trees.

In Brazil, these biofuels are normally made from waste from the exploitation of eucalyptus, pine, and black wattle. These three species of tree are among the most abundant forestry crops in Brazil and are used in industries for the production of cellulose and paper, furniture, boards, and wooden panels.

Mainly used in the industrial sector, briquettes and pellets are alternatives to charcoal, logs, and fossil fuels for the generation of thermal or electrical energy. On a residential scale, especially in Europe and the USA, they are used for heating stoves and fires. Briquettes, which are cylindrical with a diameter of about 60 mm and vary in length from 250 to 300 mm, have also been used in restaurant ovens. Pellets are also cylindrical but much smaller, between 6 and 16 mm in diameter and 25 to 30 mm in length.

Both types of fuel, according to Lopes Silva, are efficient alternatives in terms of energy and have the advantage of being more environmentally sustainable than fossil fuels. Quoting data from the literature, he gives the example: 3.5 cubic meters (m³) of wood pellets can substitute 7 m³ of raw wood due to the lower level of humidity, which gives the pellet higher energy density.

These 3.5 m³ of pellets have the same energy efficiency as 1 m³ of fuel oil, with financial and environmental gains. “In addition to being almost six times cheaper than diesel oil, considering the current exchange rate of the dollar of around R$5.20 [average value for September], they emit less greenhouse gases [GHGs] during the combustion process and are considered carbon neutral, because the carbon dioxide [CO₂] emitted during burning is recovered in the growth of plant species,” informs the engineer.

According to Lopes Silva, a study done by the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, in Holland, and The Alliance for Green Heat group, from the USA, demonstrated that using waste wood pellets and briquettes for residential heating purposes could release into the atmosphere one-tenth of the CO₂ emitted by petroleum-based fuels and one-sixth of that released by natural gas.

New inventories

In his research, the professor from UFSCar mapped the production of two types of pellets, one made from peanut shells and the other from pine waste (dry leaves, wood chips, and sawdust). He created a document called a Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) for each one. “It is the second stage of the Life Cycle Assessment, which consists of collecting environmental impact data, including all the material and energy inputs and emissions that occur in each process of the assessed life cycle,” he explains.

Data provided by the manufacturers of both the studied products, such as land use, water consumption, wood, energy demand, and emission of pollutants, were included in the inventory. Due to difficulty accessing the information, the researcher opted not to work with briquettes on this occasion. “The briquette market is very informal. Pellets already have a manufacturers association, technical quality standards, and specific certification, as well as a well-established international market.”

The next projects of UFSCar’s Sustainability Engineering Research Group (ENGS), which Lopes Silva heads, will look at the topic further and in more depth. “One of the researchers from the team, master’s student Thiago Teixeira Matheus, is studying briquettes, while another, Antônio Carlos Farrapo Júnior, is looking at proposals for public policies for these biofuels for his PhD,” the researcher informs.

The two inventories are in the final review phase to be published in the National Life Cycle Inventory Database of Brazilian Products (SICV Brazil). “In Brazil, they are the first LCIs about pellets made using primary data and available for publication,” he affirms. Previously, if you wanted to do an LCA for biomass pellets, you had to turn to international databases. The inventories are available on the SICV Brazil website.

The UFSCar studies had funding from FAPESP within the scope of the Research into Bioenergy (BIOEN) program, which has been funding research and development activities focused on the sector since 2008. The majority of the BIOEN projects focus on sugar and oilseed biomass, a natural consequence of traditional agriculture in the state of São Paulo, but the doors are open for the diversification of the themes. This is confirmed by Gláucia Mendes Souza, a biologist at the Chemistry Institute of the University of São Paulo (USP) and coordinator of the program.

She stresses that the current international scenario has made the need to develop alternative energy sources even more urgent. “With the war in Ukraine, who is going to supply the heating demand for Europe during the winter?” questions the researcher, remembering that the embargo on oil and gas from Russia, as a sanction by western countries for the invasion on Ukraine, has caused a global crisis in the energy market, with more immediate effects on Europe. “Also, for these reasons, BIOEN seeks to encourage the diversification of research. And we are able to do that due to the huge potential of Brazil.”

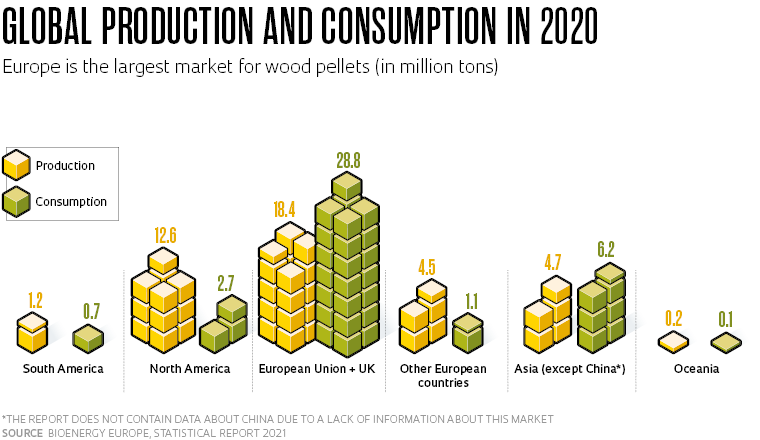

The global solid biofuel market has also benefited from the race for clean energy. European countries feel pressured by the decarbonization target set by the European Union, which foresees carbon neutrality on the continent by 2050. The global consumption of pellets reached 39.6 million tons (t) in 2020, a 7% increase compared with the previous year, according to a statistical report by Bioenergy Europe, a European trade association. European countries are the largest consumers, responding to 76% of the total—the document only covers wood pellets and does not include those made from agricultural waste.

Manufactured with the same raw material as pellets, briquettes are much larger and reach 30 cm in lengthLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP Magazine

When listing the producing countries, Bioenergy Europe highlights Brazil. “In Latin America, two countries present interesting development in pellet production, Brazil and Chile. The production records for Brazil show 1,030,000 t in 2020, with a large production capacity increase forecast from 2023,” states the report.

Given this scenario, the development of Life Cycle Inventories for Brazilian pellets is a strategic conquest, emphasizes chemical engineer Luiz Alexandre Kulay, of the Chemical Engineering Department at USP’s Polytechnic School. “Producing LCIs has direct repercussions on the competitivity of companies, especially those that wish to conquer the external market,” he stresses. “The environmental variable is becoming more and more important in decision-making processes.”

A consultant in the field of conservation and sustainability policy, economist Roberto Scorsatto Sartori sees pellets as an opportunity to add value to the national wood-processing industry. His PhD thesis, defended at the end of 2021 at USP’s Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ), in Piracicaba, proposes the insertion of “pelletization” into the timber industry for furniture and construction, from the waste generated in the production process. “It is a market that can grow but needs to be organized and have institutional support,” says Sartori.

According to the economist, the timber producers don’t feel secure investing in the pelletization process and one of the reasons is the lack of tax incentives. “Those who sell low-processed timber benefit from the Kandir Law [which exempts the payment of the Tax on the Circulation of Merchandise and Services (ICMS) for the exportation of primary products, such as soy, ore, and timber]. Pellet, although minimally processed, is not covered by this law,” he laments.

The researchers assess that exportation currently appears to be the most attractive option for national pellet and briquette manufacturers. But they see potential in this sector for strengthening the national energy mix and increasing carbon emissions trading, objectives of the National Biofuel Policy, known as RenovaBio. Created by the federal government in 2017, it has the mission of promoting the expansion of biofuels, contributing towards Brazil meeting the GHG reduction targets agreed in 2015 in the Paris Agreement.

The focus of the governmental program is measuring carbon credits from biofuel production, which is done using a tool called RenovaCalc. It calculates the intensity of atmospheric carbon emissions and generates Decarbonization Credits (CBIO) for power plants and suppliers.

For Lopes Silva, RenovaBio is an opportunity to strengthen the biofuels sector, allowing the producers to trade carbon credits on the São Paulo Stock Exchange, known as the B3. “But there is a problem that needs to be overcome,” explains the researcher. “Despite promoting the expansion of biofuels in our energy mix, RenovaBio does not include specific standards for solid biofuels or consider them in RenovaCalc, focusing only on liquid and gaseous biofuels.”

Expanding the RenovaBio policy to also cover solid biofuels, including biomass pellets and briquettes, would allow producers access to new business opportunities. In 2020, 19.9 million CBIO were traded on the B3, totaling US$162 million. “RenovaBio would need extending,” agrees Kulay, from USP. “The reality changes, and with it, the guidelines also need to be reviewed. It is important that the country has more resources for environmental management.”

Project

Life cycle assessment of biomass pellet production to strengthen the bioeconomy and the SICV Brazil database (nº 19/16996-4); Grant Mechanism, Bioen Program; Principal Investigator Diogo Aparecido Lopes Silva (UFSCar); Investment R$46,506.32.

Scientific article

SILVA, D. A. L. et al. A systematic review and life cycle assessment of biomass pellets and briquettes production in Latin America. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. vol. 157. apr. 2022.