A granddaughter of German and Portuguese immigrants, Thelma Krug is open and considerate, yet forceful when the situation requires. The São Paulo mathematician was part of the Brazilian negotiating team at international forums on environmental and climate policies for 10 years, working alongside federal government diplomats. She left that role in 2015 to assume one of three vice-presidency positions at the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), where she has been a participant since 2002. Her role as vice president was to facilitate the interaction between the member nation’s representatives and scientists, who are forecasting a gradually warming and drier global climate. This forecast is fast becoming a reality, as shown by natural forest fires in Australia, which are becoming increasingly intense and dramatic (see report).

Krug was disturbed when she returned from the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP-25), held in Madrid, Spain in December 2019, upon seeing what she called “Brazil’s backtracking” from environmental policies and from its interactions with other countries. “Brazil’s international image couldn’t be worse,” she comments.

As a researcher at the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) for 37 years, she has had an extensive career as an environmental data analyst. In 2004, she helped implement the digital version of the Amazon Deforestation Satellite Monitoring Project (PRODES), one of the principal sources of information on native vegetation loss in the region, together with the Real Time Deforestation Detection system (DETER). The mother of economist Paulo Augusto and a grandmother of two, Thelma Krug granted this interview in early January at the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), from which she retired in 2019.

Field of expertise

Spatial statistics

Institution

National Space Research Institute (INPE)

Education

Undergraduate degree (1975) and master’s degree (1977) at Roosevelt University, United States; PhD (1992) from the University of Sheffield, UK

Production

15 articles and 2 books, as coauthor

What is your assessment of the fires in Australia, which became more intense in early 2020, with smoke that reached even Rio Grande do Sul?

The 2014 IPCC report had already warned that the climate in the region known as Australasia was changing a lot. The rains have been in steady decline, while the concentration of greenhouse gases has contributed to increasing the average temperature over the past 50 years. Therefore, there was a greater risk of extreme climate events, such as more frequent and intense forest fires, which in previous years have destroyed more than 2,000 buildings and caused the death of almost 200 people in Australia.

Is there any comparison to be made with the fires in Brazil?

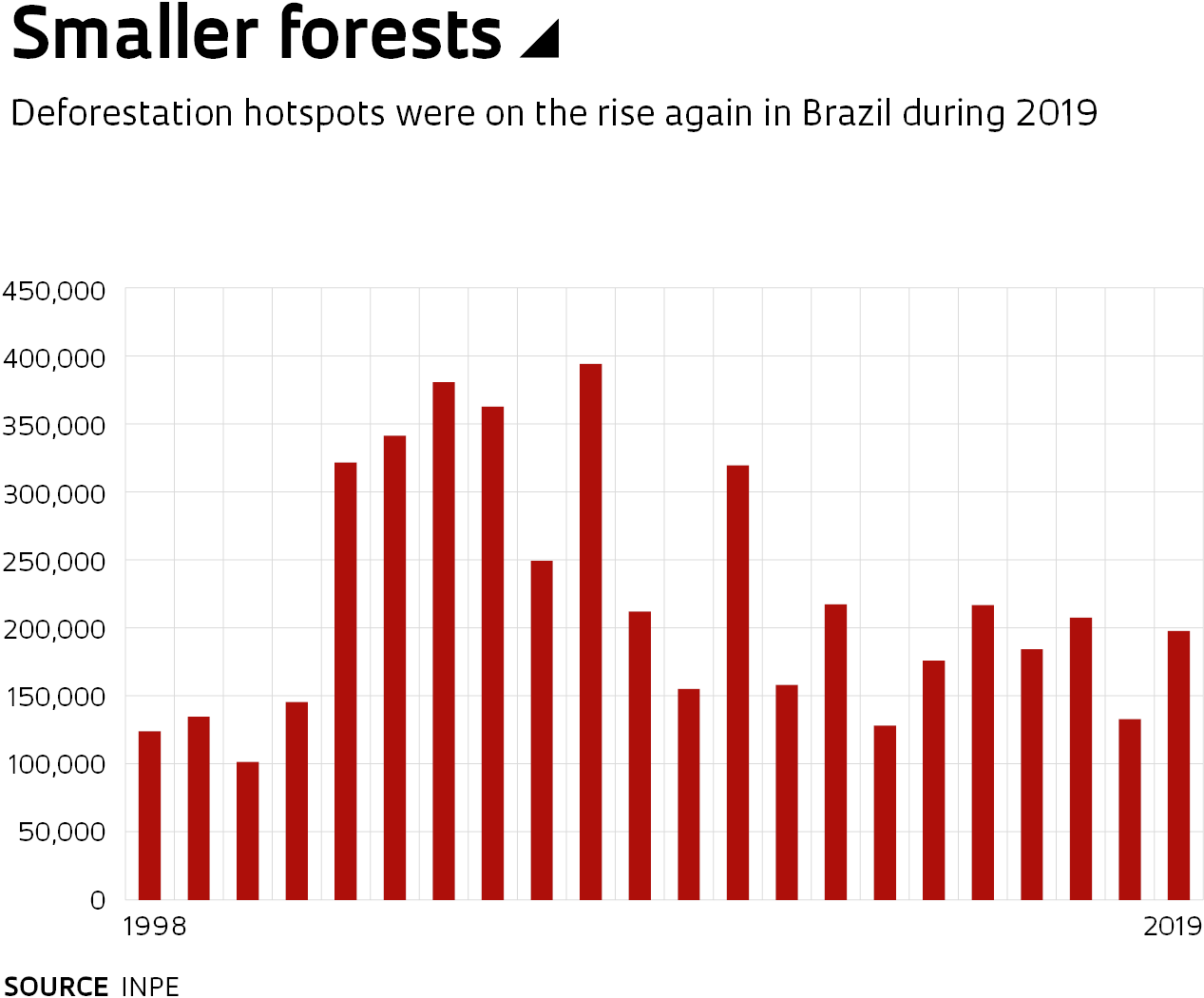

In Australia, drought and heat, intensified by climate change, have contributed to wildfires striking forests and fields since September 2019. Deforestation is not a cause of forest fires there, unlike in Brazil’s case. Here, fires are frequent and are usually associated with cleaning up deforested areas, particularly in the Amazon. Deforestation is also a vector for spreading fire, which happened in Roraima in 1998, when fire in fields burned annually to control pests spread into the forest by way of clearcut areas, causing a major forest fire. INPE statistics indicate that 2019 was a fairly typical year in Brazil [see graph]. It’s clear that the fire situation in Brazil could have been worse if the Army hadn’t been mobilized to help control the fires, in addition to providential rainfall. However, the fact that deforestation increased significantly in 2019 and that DETER had already identified twice as many hotspots by mid-January, compared to the same period in 2019, raises concerns regarding the extent, intensity, and duration of the fires, particularly in the Amazon.

INPE teams have also been indicating increased risks for extreme weather events in Brazil for more than 10 years.

The IPCC projected that climate events would become more intense, more frequent, and longer lasting with global warming. What we see today is natural climate variability combining with human activities, which are responsible for an increase of about 1º C in average global temperatures in comparison with preindustrial levels, as disclosed in October 2018 in the IPCC’s special report on global warming. In the next report, 2020–2021, scientific advances are expected to make it possible to attribute several extreme weather events to climate change, with a high degree of confidence. For Brazil, the most dramatic consequences of these phenomena will be in agriculture, with reductions in cereal production and the displacement of arable areas to different regions of the country. To mitigate these effects, EMBRAPA [the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation] is studying agricultural species that are resistant to the hotter and drier climate that we’ll have to face in the coming years, if there isn’t an ambitious and consistent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions around the world.

A recently published report by Pesquisa FAPESP shows that from 2010 to 2017 the Amazon was a carbon dioxide (CO2) source, and no longer a CO2 sink. What do you think?

There was a concern in the 2014 IPCC report assessing the interaction between climate change, deforestation, and the high vulnerability of forests to fire, which could lead to forest degradation in large areas of the Amazon. It is clear that higher rates of deforestation, with the consequent increase in fires, does increase greenhouse gas emissions—particularly carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide—since in the Amazon most of the fires are set after clearcutting forests, to clean the area for use in livestock or agriculture. With deforestation increasing, and lacking any indication of clear policies to contain it, it’s highly likely that the Amazon will continue to lose its capacity to act as a carbon sink.

Did you leave INPE for political reasons?

I officially left in September 2019, after 37 years working at the institute as a researcher, and another five as a professor and director at what was then the São José dos Campos School of Engineering, which is now part of Vale do Paraíba University. This decision was made in the face of accusations that our data on deforestation were supposedly manipulated [President Jair Bolsonaro said in July that deforestation data were false], about which I could not remain silent. INPE has become a world reference for performing annual surveys of the deforested area across the entire Amazon, and making all the data used publicly available. There is no other country that does this. It’s always possible to improve, of course. What is not admissible is to disqualify the institute’s work to justify the purchase of a data collection system, without consulting with those who really understand it, just because the manufacturer says it’s better. It’s not the first time this has happened. In 2017, I was dismissed from the Ministry of the Environment [MMA] because I questioned the purchase of a system to replace INPE’s. One argument that I’ve heard, which makes absolutely no sense, is that PRODES is still based on visual analysis of satellite data, even though there are already more advanced techniques that INPE itself has already developed and tested. But the PRODES data, which comprise the longest-running, most transparent historical series on deforestation in the world, mustn’t lose consistency through changing the estimation method. This is what earned Brazil the respect of other nations, including technology transfers from INPE to other countries. The PRODES data is used to develop public policies and the DETER data is used to support monitoring and control activities by Brazil’s environmental agencies. But unfortunately, they aren’t fully assimilated.

How so?

The two data collection systems, the PRODES annual reports and DETER’s daily alerts, generate a quantity of data that IBAMA [the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources] is unable to absorb or compare in the field, due to a lack of people and infrastructure. When I was in the ministry, I questioned how much of the DETER data the IBAMA teams used: it was 1%. So why buy another system, if you can’t even use the one you already have? Wouldn’t it be better to use this money to inspect more areas in the field? Supporters of the replacement idea claimed that INPE was making errors, but no one indicated what those errors were. There is no interaction to say which or how much data is not working.

Has the deforestation control system worked well?

Yes, it worked, because DETER was created in 2004 by the first PPCDAM [Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon]. The fourth PPCDAM and the third PPCerrado [Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation and Burning in the Cerrado], which was in effect from 2016 to 2020, have four pillars of support. First, monitoring and control, the main factor in reducing deforestation since 2004, but which has been weakened with the dismantling of IBAMA and other enforcement agencies. Second, property regularization and land management, which has advanced substantially using data from the Rural Environment Registry and should help with enforcement. Third, the advocacy of sustainable production activities, which build gradually, and fourth, regulatory and economic instruments to control illegal deforestation. Those doing the deforestation also use satellite images and can see where the enforcement will be able to go. The federal government should be at the forefront of this growing problem instead of behind it, and be continuously investing, mainly in control and monitoring. Today we can see that the country has backtracked decades in the environmental area.

Why do you say that?

We’ve lost the capacity to enforce, we’ve fiscally incentivized environmental criminals, and we’re destroying our sustainability. The federal government has adopted an environmental vision that clashes profoundly with the international perspective. To say that other countries have already deforested and, therefore, don’t have the right to criticize Brazil is an unacceptable premise, because the richest countries are trying to rebuild what they’ve deforested, understanding that one can’t go against history. There are those who still don’t believe in climate change, but the Climate Convention [the international treaty resulting from the 1992 Rio Conference] was also based on the precautionary principle. Economic development should be thought about in light of what’s possible to do sustainably, without harming future generations.

Personal archive

Vice Presidents Krug (left) and Barret, with Working Group III Coordinator, Andy Reisinger (2016)Personal archiveWhat did you see at the Madrid COP in December?

The countries were incredulous about Brazil’s backtracking. One does not enter into a multilateral negotiation making threats, saying that other countries are indebted to Brazil, especially since the Climate Convention doesn’t determine a priori which countries should benefit from environmental funds. To say that other countries are indebted to Brazil is shameful. In the two weeks he spent in Madrid, the Minister of the Environment [Ricardo Salles] was unable to build a bridge of trust with other countries, much less make them understand the position he was defending. Brazil lost a leadership role that had been achieved with respect, vision, and strategy, attributes required in multilateral negotiations. An excellent opportunity was lost to show the enormous potential Brazil has to contribute to the global effort to combat climate change, which could be expanded through international cooperation.

What could be the consequences of Brazil’s performance in Madrid?

A logical consequence of this failure—since the minister apparently didn’t obtain the hoped for financing—and of Brazil’s environmental backtracking at the meeting in Madrid, would be an even greater risk of the country leaving the Paris Agreement. It didn’t happen in early 2019 only because the scientific community protested, and agribusiness wouldn’t let it happen, so as not to put commercial deals at risk. If it did come to pass, it would be the worst decision Brazil could make. Such an exit would send a very negative signal to developing countries. Brazil has been a leader in these negotiations, and has always managed to defend its positions with a vision of environmental integrity, ensuring that what was negotiated did not jeopardize agreements with targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. This was the case in the Kyoto Protocol and in various negotiations at the Climate Convention.

What opportunities could Brazil take advantage of?

One would be to see where our niches are. In all the models evaluated by the IPCC for limiting average global warming to 1.5º C by the end of the century, CO2 emissions must be reduced to zero by 2050. But, if this is impossible, bioenergy could neutralize the excess emissions. Bioenergy is an important niche for Brazil. The government and business should be looking at this potential market and showing the world that the production of biofuels could be done sustainably, without putting local communities and indigenous peoples at risk. Instead, by revoking the decree on sugarcane zoning in the Amazon, the government is compromising what we have built over so many years, which was the idea that our ethanol was not produced at the expense of clearcutting the region.

What was it like working as a negotiator in international forums on environmental and climate policies with federal administrators?

For 10 years, from 2005 to 2015, I represented Brazil in negotiations on complex issues in forestry and land use. Today there is a much larger number of Brazilian women negotiators, mainly from the MCTIC [Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovations and Communications], but when I began representing Brazil in the Climate Convention negotiations, the percentage of women was very small. The preparatory meetings for the convention, held by Brasília officials, established the limits that each negotiator would have. Negotiation is give and take, and giving requires understanding the extent to which the country is willing to be flexible on certain elements. Negotiation means building trust, which is also supported by technical competence.

What is your role as vice president of the IPCC?

There are many. We have three vice presidents, two from developing countries, Youba Sokona, from Mali, me, from Brazil, and Ko Barrett, from the United States. There are two women, Ko and I, the first in the IPCC’s 30-year-existence to be in this position. We provide technical support to IPCC President Hoesung Lee, a South Korean economist, and assist scientists and governments in plenary meetings, when seeking consensus. The IPCC reports are approved by consensus. There are 195 member countries, but in these meetings there are usually 130, 140 attending. We are also spokespeople, since having scientists talk directly with governments doesn’t work very well. The three of us scheduled the presentations and debates for the IPCC pavilion at COP-25, which dealt with topics that ranged from the knowledge of indigenous peoples to the use of computational models for detailing national inventories of greenhouse gases. The IPCC has a fixed membership of no more than 13 people and a low budget of US$8 million per year, used mainly to finance the participation of authors from developing countries in the face-to-face meetings. Everyone works on a voluntary basis.

Personal archive

At a 2017 IPCC meeting in Montreal, CanadaPersonal archiveWhat are the IPCC’s priorities?

One is communication, in order to provide more access to the studies. Because the language of the IPCC reports is often complex, each is given some simple key messages, without the scientific complexity, but which serve to arouse curiosity and stimulate the exchange of ideas with broader audiences. For the report on 1.5º C warming, the messages were “every action matters,” “every year matters,” and “every extra bit of warming matters.” I’ve already been to several places where these messages are being announced. In Madrid, for example, the message that “every action matters” has been widely disseminated. With these simple messages, the IPCC seeks to arouse curiosity, so that people will seek more information for themselves, instead of being discouraged by complicated language.

Where do your negotiation skills come from?

You can’t teach that. My background is mathematical, but I wish I’d been a psychologist. Perhaps this is where I get an ability to deal with people well, without being pushy. I married early, by current standards, at 19, in 1969. My son was born in 1972, and soon after we left for the United States so that Paulo Renato de Moraes, my husband at the time, could get his doctorate. In less than a year, I was bored with the life of a housewife and told Paulo Renato that I wanted to continue studying. He asked how we would pay for it, because we were living on his grant from CNPq [the National Council for Research and Technological Development]. But we found a small university in downtown Chicago, Roosevelt University, and I would just take as many courses as I could pay for. It was Paulo Renato who chose mathematics, because I was good at it, and in the tests I always got A’s. I took psychology as a minor. To pay for the courses, I took babysitting jobs, did typing jobs in the middle of the night on a noisy machine, and worked as an interpreter for visiting Brazilian businessmen. After a year, I won a scholarship, based on good performance, for the following term. I finished my bachelor’s degree in two and a half years—normally it takes four years—on scholarships until the end. I was thinking about what to do next when the university invited me to do a master’s degree, with a scholarship, this time without a performance requirement.

What was your return to Brazil like?

When I came back in 1976, I went to the São José dos Campos School of Engineering, and applied to teach classes in integral and differential calculus, operations research, and statistics. I was put in an extremely awkward position. The director told me that he didn’t need new teachers and then invited my then husband to teach statistics in the engineering program. I asked the director why I had been refused a position and he explained that as a woman, I wouldn’t be able to maintain control of the classroom. I would be the first female teacher for those classes. For me, it was hugely frustrating, but, the day before classes were to start, not having found another teacher, they called me to take the classes, with a warning that I would only actually be hired if I managed to survive the students, some of whom were older than I was. It wasn’t easy, but I was hired as a teacher and later elected director of the college. Even today, I’m the only woman who’s on the “wall of directors.” Times may not have changed that much.

One consequence of the failure in Madrid would be an even greater risk that Brazil will exit the Paris Agreement

INPE was also a macho place, right?

In 1982, when I started at INPE, there were only a few women in research. Márcio Barbosa [director from 1988 to 2000], after consulting with researchers and technologists, invited me to assume the head of the institute’s Remote Sensing Division in 1992, as soon as I returned from receiving my doctorate in England. Participating in the LBA [Large Scale Biosphere-Atmosphere Experiment in the Amazon] and working with national and international teams helped me greatly in understanding the complexities of the Amazon, the relationship of deforestation and forest degradation to local and regional climate, the dynamics of land use, and hydrology. Because I worked very closely with the government, I understand the importance of science in decision making. The real trick is being able to bridge the gap between science and politics. I see myself more in this role, mainly in relation to the issues of deforestation, fires, and climate change.

So what are your plans now?

As soon as I retired I received an email with a call for consultants, which required experience in national greenhouse gas inventories, working knowledge of Climate Convention decisions, and familiarity with field sampling and data analysis. It fit like a glove and I became a consultant for the Coalition of Rainforest Nations, which today has 53 member countries. The Coalition helps member countries develop their national inventories and submissions for REDD+ [financial incentive for developing countries that reduce greenhouse gas emissions resulting from deforestation and forest degradation]. The consultancy should help to improve the quality of inventories so that they can be used as a tool for identifying reductions in emissions and increases in removing gases from the atmosphere, particularly those related to commitments by countries determined under the Paris Agreement.

What do you do when you have spare time?

I call up friends and prepare gnocchi with my own homemade sauce. I love having people over. I have to discipline myself to do something other than work. At the end of last year, I took my laptop to my son’s house in Caraguatatuba, on the coast of São Paulo, but I didn’t open it. I spent the days creating mathematical challenges with my grandson Luca, 7, who wants to be an astrophysicist, and was interested in how I would solve the challenges he had proposed. He was very disappointed that he had not been accepted into the short course in astrophysics at INPE. My other granddaughter, Ana Luíza, 17, is studying to be a veterinarian; my passion for animals has infected her.