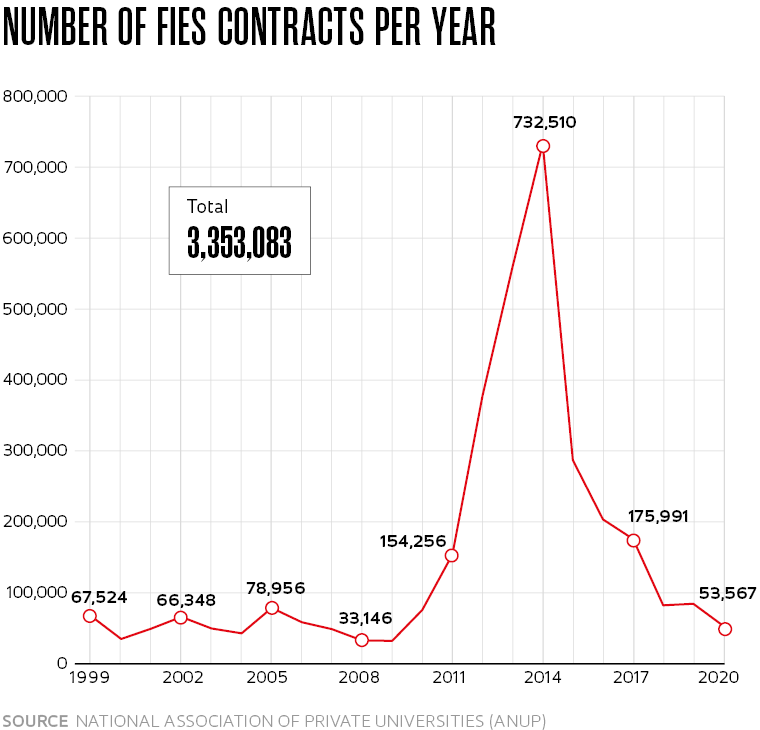

Established in 1999 to fund higher education in private educational institutions, the Student Financing Fund, better known as FIES, has since become a key element in making universities more accessible. Serving more than 3.3 million students throughout the country, in mid-2021 the program reached an unprecedented milestone: more than 1 million defaulters, or debtors whose payments have been overdue for at least 90 days.

Upon graduating from the human resources management technology program at the University Center of Curitiba (UNICURITIBA) in 2014, 30-year-old Bruna Silva, from Rio Grande do Sul, began the 18-month grace period before her first payment was due, according to the rules in effect at the time. The following year, when she started receiving her monthly invoices of R$250, she still had not been able to get a job that would allow her

to pay them—and that remains the case to this day. The unpaid installments began adding up, now totaling R$5,000. “It makes me anxious knowing that renegotiations are uncertain and that I run the risk of losing control of the debt, which grows every month. In addition, my sister, who was my guarantor in the contract, now has bad debt linked to her name,” says Silva, who has already considered taking out a loan to settle the outstanding balance. “It is frustrating that I can’t even get an internship in my field,” she adds.

Last July, Jenilson Lima, 29, from the state of Ceará, got his first payment slip for his student debt, which paid for his degree in business administration at the Estácio Ceará University Center in 2019. Unable to make the monthly payments of R$470, in September he went to the Caixa Econômica Federal agency where the contract was signed to renegotiate the monthly dues. “I was informed that I need to follow the program’s website and wait for renegotiations to reopen,” says Lima, who also saw his name included in the registry of bad debtors. “I got a job at a local real estate agency, but in addition to the FIES payments, I also need to pay rent and other domestic expenses,” he shares.

Currently, candidates for FIES funding include students who get at least 450 points in the National High School Exam (ENEM) and achieve a grade higher than zero in the essay. Another key prerequisite relates to the applicant’s household income, which cannot be higher than three times the minimum wage. For those interested in obtaining higher education, every six months a notice is published on the FIES website detailing how to register and to select three possible undergraduate programs at participating institutions. The universities must meet the assessment requirements determined by the Ministry of Education (MEC) via the National Fund for Educational Development (FNDE), the body responsible for implementing policies in this field.

In 1992, with the passing of Bill no. 8436, the Educational Credit Program (CREDUC) was established. CREDUC was discontinued in 1999 after the FIES was established through a provisional measure, and its assets were incorporated into the new fund. In 2001, FIES was sanctioned by Bill no. 10,260. In 2014, it recorded its highest ever number of contracts signed, with more than 730,000 people joining the program. In comparison, the previous year had seen 559,891 new loans. “The growing default rate we see today is directly related to the large number of contracts signed in those two years, with debtors having to make payment now,” explains public management expert Flávio Carlos Pereira, who worked as general coordinator of operational support for student financing at the MEC from 2012 to 2020. Today, Pereira is a consultant for the National Association of Private Universities (ANUP).

For those who joined the program before 2017, like Silva and Lima, the rules stipulate a grace period of three semesters starting from the date they finish the program. In other words, debt repayment should be aligned with the student joining the workforce, preferably in their chosen field. The maximum term for loan repayment is three times the duration of the program: for example, those who obtained a four-year degree would have up to 12 years to pay off the loan. “In this former format, it doesn’t matter whether the person is employed or not; they need to make the payment,” adds Pereira.

With the growing economic crisis, the dream of graduating from university has become a nightmare for thousands of undergraduates. As with any financing agreement, failure to make payments results in credit restrictions not only for the debtor, but also for their guarantor.

According to ANUP, the previously fixed interest rate for this program is no longer subsidized by the government and thus began to fluctuate with inflation. In 2015, for example, it was 3.4% per annum. In 2017, it reached 6.5%. Since 2018, the amounts have been corrected according to the Broad National Consumer Price Index (IPCA), which can reach 10%. “At a time of crisis, with high unemployment rates and pessimistic prospects, many students drop out of programs for fear of incurring even more debt,” explains Pereira. Those who decide to quit university halfway through must still pay the debt incurred up to that point until notification of withdrawal.

The financing program was changed in 2018 in an attempt to contain the growing default rate. Known as the New FIES, the program has eliminated the grace period that had been in effect until 2017, instead aligning payments with the debtors’ initial income. In this case, as soon as they graduate, the debtor must begin paying off their debt with payments that range from 8% to 12% of their salary. If unemployed, they can suspend payments for as long as necessary, while still paying the R$50 fee for services provided by the financial agent. Previously funded by the program, in this new version, the debtor is also responsible for the R$5 monthly payment of loan protection insurance, which guarantees the payment of installments or settlement of the outstanding balance in case of death.

Unlike the previous version, in which the student could choose to borrow amounts that covered 50%, 75%, or 100% of their tuition, with the New FIES, it is practically impossible to get the entire amount covered. From the start of their university education, the student must pay for a portion of their tuition fee. The calculation of this amount depends on the program’s score in the National Higher Education Assessment System (SINAES), monthly tuition, and the student’s household income.

The algorithm-powered analysis determines the percentage of the tuition to be covered for each applicant. In 2014, the maximum amount covered in each contract was around 94%; in 2020, it fell to 76.4%, according to ANUP. More expensive courses—such as medicine, for example, whose monthly tuition can reach R$10,000—pose even more of a challenge. “In this case, a student with family monthly income up to three times the minimum wage will have to pay monthly tuition of R$3,000, which is unfeasible for most young people,” says Pereira.

One of the solutions to lower the number of FIES debtors is migrating overdue contracts from the old format—those signed before 2018—to the new format, under which the payments depend on the debtor’s income. “This is already provided for under 2017 Bill no. 13.530, which allows for the voluntary transfer of contracts to the New FIES, once approved by the program managing committee,” explains the ANUP consultant. “There is no doubt that many would request the transfer of their contracts to this format, hoping to clear their names from the list of defaulters with credit protection services.” The law, however, does not ensure that renegotiation of the rules automatically adjusts the outstanding balance of the former contract, which does nothing to mitigate the debtors’ current situation.

Since its inception, the program has offered debt renegotiation opportunities at least once a year, but without defined dates. In 2019, for example, the program offered to renegotiate the monthly payments, but without reducing interest and fines. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, in 2020 Bill no. 14,024 temporarily suspended the financial obligations of the beneficiaries of the fund. Up until the publication of this issue, Bill no. 1.133/2021 was being processed in the House of Representatives, adding one more year to this period of temporary suspension of debt payments.

“Even those who are able to make the payments in advance face challenges,” shares lawyer Fábio Henrique Pereira de Araújo, from Modal Assessoria Jurídica, which has a division specializing in educational law. One of the debtors’ main complaints is how hard it is to obtain solutions through the FNDE communication channels. “Some of my clients have graduated from medical school and are looking to make advance payments so they can obtain other kinds of loans,” explains Araújo. Because FIES can negatively affect credit analysis and approval for mortgages, for example, some debtors turn to the judicial system to correct, review, or even renegotiate their debt. The FNDE did not respond to requests for an interview.

The challenge in obtaining information about FIES debt renegotiation has given rise to several discussion groups on social media. Some include more than 50,000 users, who ask daily questions on how to navigate the rules of their contracts and, in many cases, how to handle overdue payments. “Although FIES is a social program that involves several agents, the students are the ones who primarily carry the burden,” says Belinda Mandelbaum, from the Department of Social and Labor Psychology at the Institute of Psychology of USP and coordinator of the Laboratory of Family, Gender Relations and Sexuality Studies. “There was a time when students were encouraged to sign up for the program. Student loans were advertised everywhere,” recalls Mandelbaum, reinforcing the fact that this issue coincides with a moment of crisis, accentuated by the pandemic. “Personal and professional achievement does not come simply from completing postsecondary education, but also from being able to honor one’s commitments. When young people are unable to do so, it clearly becomes a source of anguish for them,” she assesses.

Sólon Caldas, executive director of the Brazilian Association of Private Universities (ABMES), believes FIES is moving increasingly farther away from its social role of training new professionals to meet the government’s fiscal policy, which has, since 2015, led to lower numbers of students signing up for the program. In the first half of 2021, 27,000 new contracts were signed. “We do not defend debt amnesty, but a renegotiation policy that meets the needs of those in debt,” he considers.

Despite the uncertainties that currently concern so many young professionals, experts recommend caution, to avoid impulse decisions that could aggravate their situation. “Taking out additional loans to pay off the overdue FIES balance could lead to even bigger financial problems. Despite being a loan, the fund is part of a public policy. Waiting for renegotiation periods or pressing for the revision of migration rules is still the best thing to do, in most cases,” advises Pereira, from ANUP.

Republish