Collaborative research, which mobilizes scientists from different institutions and countries, has gained momentum over recent years due to easier communications and an increase in large, internationally organized projects. A group from the Dalian University of Technology, in China, put together a set of indicators that allow a view of various collaboration profiles between the 41 countries in the world doing the most scientific production. In an article published in May in the journal Scientometrics, the authors compared the collaboration profiles of these nations and observed striking distinctions. While scientists in the United States cooperate in greater numbers with their own academic colleagues and within the country itself—which, after all, is the principal scientific power on the planet—researchers from nations like Switzerland, Iran, and South Korea follow an inverse trend and invest more frequently in partnerships with colleagues from abroad or in industry.

The countries of the European Union stand out due to the connections they establish with each other, and although China and Brazil have multiplied the frequency of their collaborations in recent decades, the increase is seen in more internal partnerships than with international ones. “Research collaboration is becoming not only more extensive, but also more diverse,” write the authors of the study, whose primary researcher is information scientist Zhigang Hu.

The group took into account data regarding collaboration on scientific articles at three levels: authors, institutions, and countries. Based on these indicators, they then produced national rankings. The study is attracting attention because of how it compiles lists of the 41 countries through different types of collaboration and at two different moments in time, in the early 1980s and the late 2010s. The comparison between the two periods indicates who has made the most progress. Articles published by more than 20 million scientists who were active between 1980 and 2019 were analyzed. The data were obtained through InCites, the scientific production analysis platform from the Clarivate corporation, integrated with the Web of Science (WoS) database. The 41 countries were selected based on the volume of their scientific production. Each of the nations chosen was responsible for at least 0.5% of the articles published globally between 2015 and 2019.

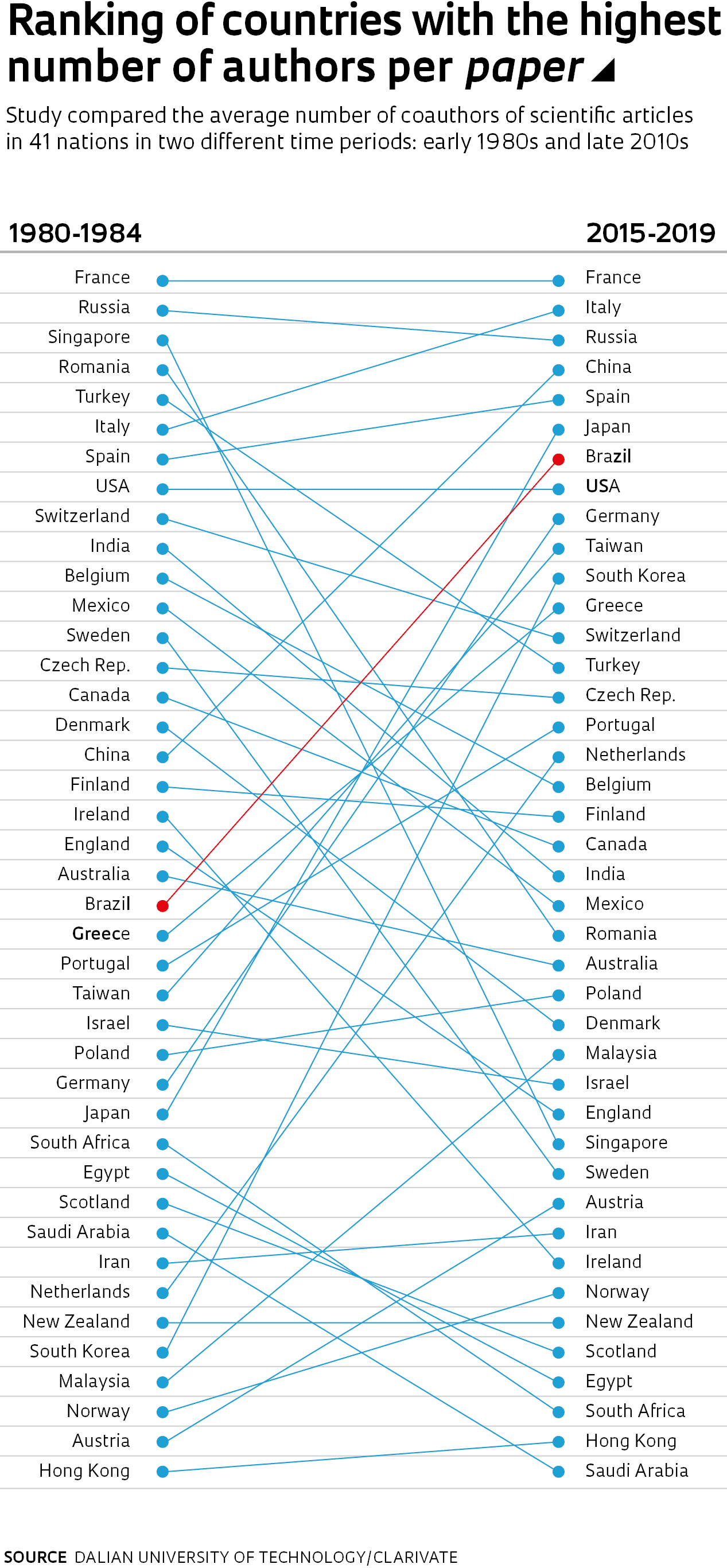

One of the rankings shows the countries with the highest number of authors per article. The study indicates that the average number of authors per article published rose from 2.2 in 1980 to 7 in 2019. France appears in first place for both periods studied. In the early 1980s, French articles had an average of 1.36 authors, while by the late 2010s the score was 8.83 authors per paper. The United States remained in the same position—8th place—in both periods, while China went from 17th to 4th place, from 1.43 to 5 authors per article in each respective period. Another analysis shows how collaboration between institutions has progressed; the indicator, in this case, is the number of universities and research centers to which the authors of the articles are linked. The number of institutions per article grew from 1.59 in 1980 to 2.66 in 2019, with France again taking the lead. One explanation for this may have to do with university reform in France, which began in the 1970s, and split up its major universities. In Paris, for example, one university gave rise to 13 independent institutions.

The number of countries to which article authors are linked rose from an average of 1.14 to 1.48. “This shows that the growth in collaborations mainly comes from the increase in team size [or intra-institutional collaboration], instead of inter-institutional or international collaborations,” wrote Hu. European countries dominate the top positions of the ranking from 2014 to 2019, with Greece, Austria, Finland, and Belgium in the lead, while in the early 1980s rankings, none of these countries appeared in the leading group. The improvement, in this case, is possibly linked to the advent of the European Union in the 1990s, which created a common research space among its 27 member countries, with programs aimed at collaborative production. The most recent example was Horizon 2020, which invested €80 billion in research and innovation.

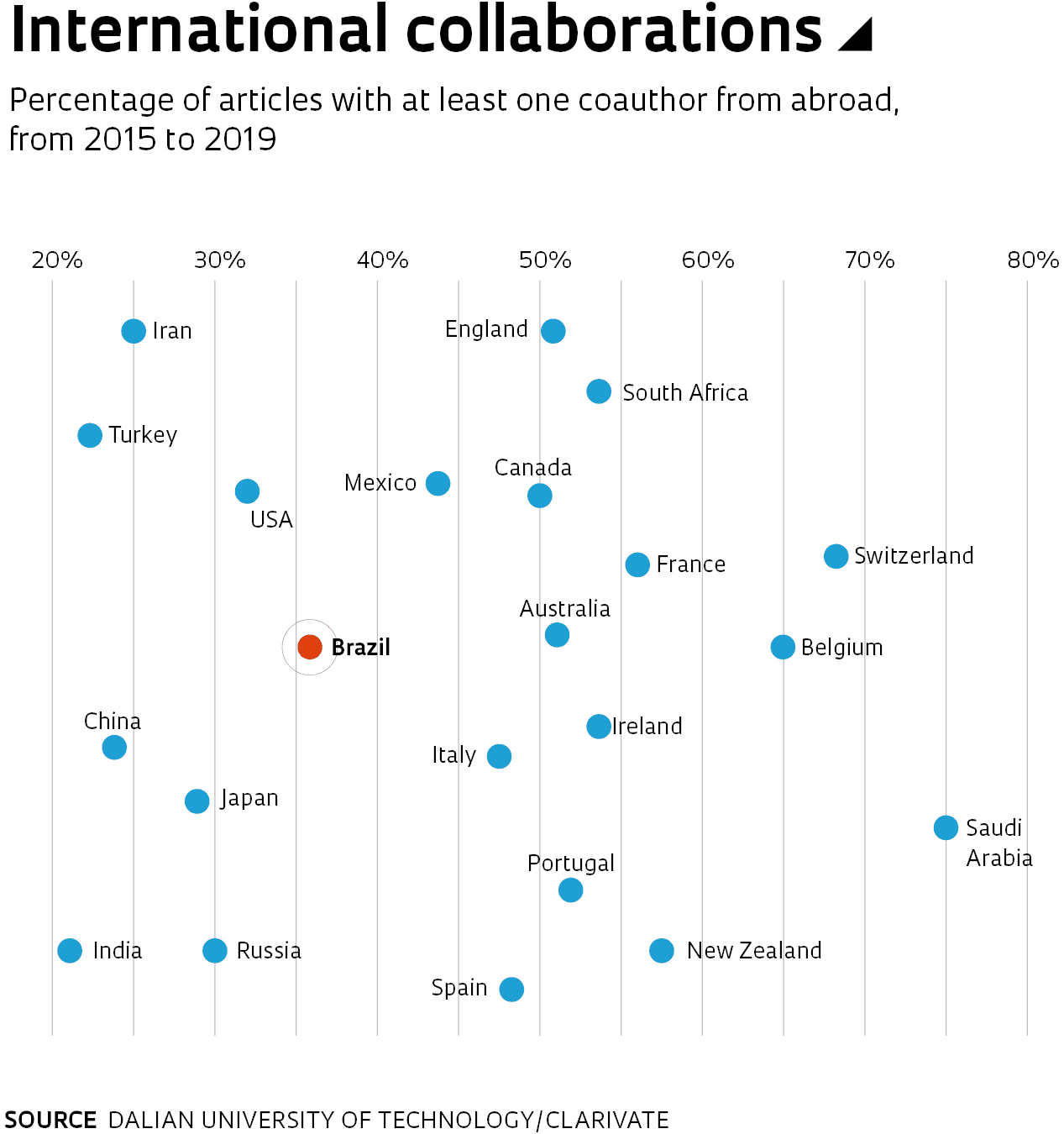

The study also examined an indicator explored in other studies: the percentage of scientific production in each country that is a result of international collaboration. Here, the leader was Saudi Arabia, conducting 75% of its scientific production in conjunction with other countries. This rate is much higher than that of European Union countries such as France, Finland, Austria, and Belgium, which score in the range of 55% to 65%. Brazil was at 36%, the United States, 32% and China around 24%. Finally, there is the ranking of collaborations with industry, which is led by Switzerland; just over 7% of its production was done in cooperation with authors linked to companies in the late 2010s—and it was also number one in the 1980s. The United States, which appeared in fourth place from 1980 to 1984, fell to 15th position in the period 2014 to 2019. Just over 3% of its articles were authored in partnership with corporate researchers, a sign that despite industry’s notable interest in research and innovation—demonstrated by patent rankings, for example—the environment in which the greatest volume of knowledge is produced is the university.

Several European countries, such as Sweden, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Germany, and Austria, lead the United States in industry collaboration, with coauthoring rates for articles ranging from 4% to 6.5%. The cohort of companies considered in the WoS database is limited to large corporations in the United States and Europe. One curious fact in the study is its comparison of the list of companies that collaborated most with researchers, five of which appear in the top ten both in the 1980s and more recently: Swiss firms Novartis and Roche, the US-based firms IBM and Pfizer, and the British company, Glaxo. There was a shift from electronic companies to biomedical companies over the two periods.

The change in performance in Brazil’s indicators was expressed clearly by the size of teams of coauthors collaborating between institutions. Between 2014 and 2019, each paper in Brazil included on average 4.5 authors and 1.6 institutions. Information scientist Samile Vanz, a professor at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, notes that the country’s performance indicators may be biased. In the 2000s, dozens of journals from Brazil were included in the Web of Science platform, and the growth in the number of collaborations is also related to the higher number of papers from Brazilian magazines in the database. “This may explain why much larger increases are seen in collaborations within the country, which are more frequent in articles in Brazilian journals than with researchers from abroad,” says Vanz, who, in 2009, defended her doctoral thesis on international collaborations in Brazil. In her view, raising the level of international cooperation remains a challenge for Brazil’s scientific community. “Incentives for making Brazilian science more international need to be amplified. There’s a large geographical distance between us and the United States and Europe, and a significant language barrier. Without strong policy to encourage international collaboration, our tendency is to do science that only has regional impact,” says the researcher, who did part of her doctoral research at Dalian University.

Previous studies show that Brazil increased the number of articles written in international collaboration during the 1980s and 1990s. According to data from Elsevier’s Scopus platform, the number of Brazilian articles written with international collaboration exceeded 30% in the mid-1990s, then dropped to an average of 25% during the 2000s, and has risen again in recent years, reaching 32.5% in 2018. According to Scopus, the number of Brazilian articles with international collaboration is higher than countries such as South Korea, which is around 30%, China, around 23%, and the global average, which is just above 20%. The Scientometrics article shows that other countries increased their international collaborations more rapidly than Brazil. “European countries all rose considerably, as a result of the period when the European Community was formed. As a result, all the others fell,” explains physicist Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz, a professor at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and FAPESP scientific director from 2005 to 2020. He also notes that countries like Canada and Mexico collaborate internationally more than Brazil, thanks in good measure to their ongoing interaction with the United States, a nation that both countries collaborate with on 30% or more of their articles. The United States is also Brazil’s main partner, but the level of collaboration is around 15% of its articles.

Biologist Jacqueline Leta, a researcher at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), notes that very high rates of international cooperation don’t necessarily indicate better or more relevant science. “The data from this study shows that some countries have been successful at investing in both internal and external collaboration, and have managed to strengthen their scientific communities, while others are overly dependent on outside research. Conducting 75% of its production in partnership with other countries, as is the case with Saudi Arabia, signals a lack of autonomy,” says the researcher, who has authored studies on the progress of international collaboration in Brazil from the 1980s to 2000.

She believes the growth demonstrated by Brazil should not be underestimated. “It means that we’ve expanded our connection with researchers in other countries at the same time that we’re strengthening our internal connections. That’s a sign of maturity,” she states. Leta notes that cooperation is necessary for multiple reasons. “Science today is highly specialized, and collaborations are a fundamental tool for enabling these specializations to exist. Collaboration allows certain gaps to be filled, such as having access to sophisticated techniques, or a research partner with a specific specialization, or equipment and supplies that are otherwise unavailable,” she explains. In her view, there are many factors that lead to the pursuit for cooperation. “Today, there are gigantic networks of researchers working on complex projects, which yield articles with over a thousand authors, with each making a specific contribution. Brazil participates in these networks.”

According to the Chinese researchers’ study, Brazil conducts 1.4% of its articles in collaboration with industry partners, while more than 7% of Switzerland’s scientific production results from this type of partnership. Among the other BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), China is at almost 2%, while Russia and India are around 1% for this indicator. Other authors criticize the methodology used by the University of Dalian researchers. Data compiled last year by Brito Cruz show that in 1989, just over 0.5% of USP’s scientific production indexed on the Web of Science database included corporate researchers as coauthors. In 2017, the proportion was 2.7%. The rate observed at UNICAMP increased from 1.5% to 2.5% over the same period, while UNESP went from zero in 1989 to close to 2% of articles being coauthored with company researchers in 2017. “You have to be careful when evaluating collaboration between universities and industry, because the databases have difficulty in identifying articles done in partnership with researchers from small and medium-sized companies, and in general only record those from large corporations,” says Brito Cruz. He worked with Clarivate to identify numerous Brazilian articles connected to industry, published in a report last year that was also based on data from InCites.

The analysis conducted by Brito Cruz involved obtaining data from all scientific documents with at least one author in Brazil, which amounted to over 300,000 records of authors affiliated with more than 22,000 organizations. The research on corporate collaborations involved searching for documents that had authors from one of 4,000 firms identified in the business sector and also at any university in the country. The report shows that in 2017, Brazil published about 1,600 articles with authors from both universities and companies—a number four times higher than the same figure from 2005. Among the 50 companies that published the most articles in collaboration with Brazilian universities from 2015 to 2017 are 17 Brazilian and 33 multinational corporations. The chief standout according to the study was Petrobras, at 14%, followed by companies such as Novartis, Vale, Pfizer, IBM, GSK, AstraZeneca, and Embraer. However, Jacqueline Leta also has reservations about the use of indicators previously studied using analytical tools. “Accounting for study authors accurately isn’t always an easy task, due to the need to identify and remove inconsistencies in the entries of names of both individuals and institutions. I prefer to analyze raw data, rather than analytical spreadsheets with consolidated data,” she says.

Scientific articles

LETA, J. and CHAIMOVICH, H. Recognition and international collaboration: The Brazilian case. Scientometrics. Vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 325–35. 2002.

HU, Z. et al. Mapping research collaborations in different countries and regions: 1980–2019 Scientometrics. no. 124, pp. 729–45. 2020.

Research in Brazil: Funding excellence analysis prepared on behalf of CAPES by the Web of Science Group. Clarivate Analytics. 2019.