Rare earth elements (REE) are part of a wide group of economically important, strategic minerals essential for the production of technologies associated to the green economy and low-carbon industry. Lithium, niobium, silicon, graphite, and copper are also considered critical in this regard. To stimulate the development of this industry in Brazil, in June of this year the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) and Brazilian Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP) selected 56 production projects, with an initial overall funding allocation of R$5 billion, of which 10 involve REEs.

– Brazil invests in research to master the production cycle of rare-earth minerals and supermagnets

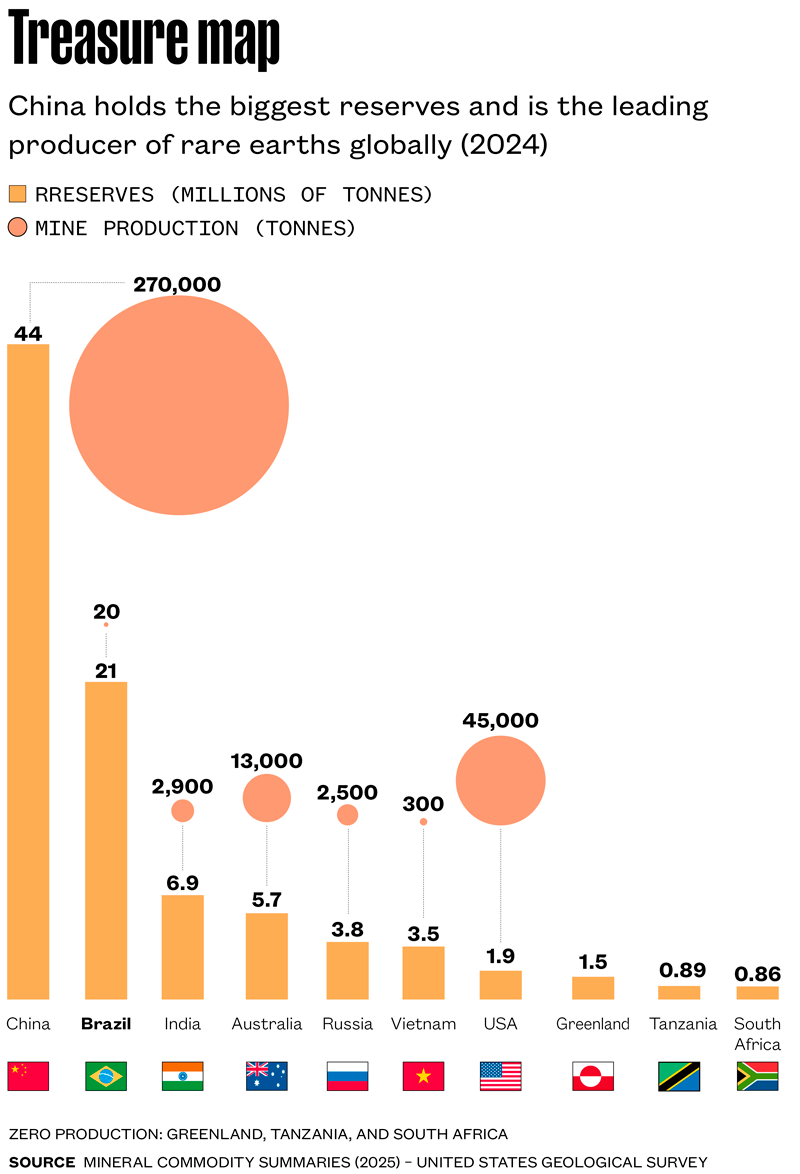

Brazil holds 23% of identified rare earth deposits, equivalent to 21 million tonnes (t) and second only to China, which has deposits totaling 44 million t, or around 49% of the total; according to data from the United States Geological Survey, the Asian country is globally the leading manufacturer of super magnets using these raw materials. Brazilian production of rare earths is in its early stages—in 2024, only 20 t were extracted against 270,000 t by the Chinese—and magnets are yet to be manufactured in the country (see infographic below).

The United States, which holds only 2% of global reserves (1.9 million t), is seeking to sign agreements with other countries to guarantee the supply of these minerals and not depend solely on the Chinese, who are creating barriers to the exportation of rare earths, hampering competition in the super magnet market. US production last year totaled 45,000 t, less than 20% of Chinese output, and is insufficient for the country’s demands. The Trump government has expressed interest in reserves in Brazil, Ukraine, and Greenland, among other countries.

According to information from the Brazilian Geological Service, the National Mining Agency, and consolidated technical studies, key deposits with economic potential in Brazil can be found in the states of Minas Gerais, Goiás, Amazonas, Bahia, and Sergipe. Rare earths are normally found intermixed and aggregated to more than 200 minerals, primarily niobium and phosphate.

They can be extracted from compact rock, or ionic clay, the latter a weathered substrate that is easier to mine, as found at the reserve in the municipal area of Minaçu, upstate Goiás. Operated by the US-British corporation Mineração Serra Verde, it is one of the few ionic clay mines operated outside Asia, and the venture is Brazil’s sole commercial producer.

More easily exploited, ionic clay reserves are a recent discovery in Brazil going back no further than 10 years, explains chemical engineer Ysrael Marrero Vera, head of the Extractive Metallurgy Service at the Center for Mineral Technology (CETEM) in Rio de Janeiro. Many rare earth deposits in the country are difficult to extract, with higher operational costs.

Serra Verde has set the target of producing 5,000 tonnes per year of a mixed concentrate of oxides with neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), terbium (Tb), and dysprosium (Dy), according to the company website. According to an article in leading Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo, the company’s output is purposed for export, primarily to China. No comment was received from Serra Verde when contacted by Pesquisa FAPESP.

Mineração Serra Verde Aerial view of the rare earth processing facility at Mineração Serra Verde, Minaçu, Goiás StateMineração Serra Verde

Researchers interviewed by the reporting team draw attention to the fact that mining companies currently exploiting or planning to exploit rare earths in Brazil are either based overseas or operate with overseas capital. They are also concerned that Brazil may once again miss the opportunity to lead in the extraction and processing of rare earths—through the 1950s and until the mid-1960s, the country was one of the primary suppliers of rare earth oxides globally. The materials were refined by the company Orquima, which extracted from monazitic sand deposits containing rare earths and uranium, and sold its production of oxides to overseas buyers.

Orquima became a state-owned concern, and after some years the government decided that it was not worth investing further in rare

earth processing. “All the investment in technology and human resources was practically lost, and when rare earths obtained more aggregate value in the 1970s and 1980s, Brazil was already out of the race,” wrote chemists Paulo Cesar de Sousa Filho and Osvaldo Antonio Serra, of the University of São Paulo (USP), in an article published in 2014 in the journal Química Nova.

As with other elements, extraction of rare earths has environmental impacts: at open-pit mines, vegetation is grubbed, soil erodes and is compacted, and local biodiversity is lost. There are also other issues: when rare earth concentrate is produced, elements such as lanthanum (La) and cerium (Ce) may be present in a much greater proportion than neodymium and praseodymium, the two REEs with the greatest economic potential. This means that the final product is rare earths with limited market demand (lanthanum and cerium). Moreover, certain minerals such as monazite have radioactive elements like thorium and uranium, generating potentially radiotoxic waste. “It’s not enough to master the rare earth production cycle; it needs to be sustainable,” says chemist Henrique Eisi Toma, of the USP Institute of Chemistry (IQ-USP).

With process sustainability in mind, CETEM and other research groups and institutes have turned to the recovery of rare earth elements from used, discarded materials such as batteries, magnets, and fluorescent bulbs, through a recycling process known as urban mining. “We collect magnets after use and study the possibility of recovering rare earths contained within them. Certain metallurgy techniques are applied in this process, such as leaching, purification, and separation,” says CETEM’s Vera.

FAPESP supports research into urban mining at the São Paulo State University (UNESP) Institute of Chemistry, Araraquara campus. Between 2016 and 2020, Latin American and European countries collaborated to recover elements from discarded fluorescent bulbs, since the powder that coats the glass tubes contains terbium.

“This powder has enormous added value, and also contains mercury, which is toxic, so indiscriminate disposal of fluorescent bulbs in landfills is objectionable,” comments chemist Sidney José Lima Ribeiro, coordinator of the IQ-UNESP Photonic Materials Laboratory, going on to say that terbium (Tb), europium (Eu), and yttrium (Y) can be recovered from the bulbs. These elements are used in the development of ceramics, fine luminescent films, and optical sensors, and such applications are the focus of the UNESP group. “We are developing methods to extract rare earths and use them in our studies,” adds the researcher. One line of research, funded by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), involves using the bacteria Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans to produce sulfuric acid for rare earth recovery through a process of bioleaching, coordinated by chemist Denise Bevilaqua of IQ-UNESP.

In an article published this year in ACS Applied Bio Materials, UNESP researchers came up with a possible use for a rare earth compound in nanoplatforms to control the release of the anticancer drug doxorubicin. Adding the elements to the material allows the drug to be released using infrared light, according to the study, whose lead author, Marina Paiva Abuçafy, received a postdoctoral fellowship grant from FAPESP.

Urban mining is also the subject of a project funded by CNPq aimed at transforming magnets used in wind turbines, older computers, and magnetic levitation railroad guideways—such as those used in an ongoing project at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 342)—into new magnets or materials. “Processing a used magnet from tomography apparatus or a wind turbine is identical to the process for a brand-new alloy,” says physicist Sérgio Michielon de Souza, of the physics department at the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM).

Souza is also at the helm of another project: coordination of a new enterprise of the Brazilian National Institute of Science & Technology (INCT) dedicated to rare earths, known as MATERIA – Advanced Rare Earth-Based Materials, approved this year. With investments of R$10.2 million over the next five years, the initiative has a broader set of objectives than the previous project—INCT Rare Earths—since it is not restricted to the specific magnet production chain, but geared toward all the different possible rare earth applications, which include the production of photovoltaic solar cells and thermoelectric materials.

The very challenging target of this INCT is to turn the rare earth cycle fully Brazilian, from extraction to applications, over the next five years, says Souza. “We will be working to produce new materials or magnets of the same quality as those made in China.” Some fifteen institutions are part of the new INCT: eight universities, five research centers and institutes, and two technical education institutes. “This is a significant differential, as it involves people from the most basic level of instruction to the most advanced,” he concludes.

The story above was published with the title “Urban mining” in issue 356 of October/2025.

Projects

1. Recovery of lanthanides and other metals from electronic waste (n° 16/50112-8); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Sidney José de Lima Ribeiro (UNESP); Investment R$202,138.60.

2. Development of core-shell-shell nanoparticles based on UCNP, ZnO, and ZIF-8, coupled with a bacterial cellulose membrane to combat microbial resistance through photoactivation (n° 24/50887-4); Grant Mechanism Fellowships in Brazil – Program for Retaining Young PhDs; Principal Investigator Sidney José de Lima Ribeiro (UNESP); Investment R$140,880.00.

Scientific articles

ABUÇAFY, M. et al. Core−Shell UCNP@MOF nanoplatforms for dual stimuli-responsive doxorubicin release. ACS Applied Bio Materials. Vol. 8, pp. 2954–64. Apr. 2025.

REBELO, Q. H. F. et al. The role of mechanochemistry and heat treatments in shaping the magnetic and optical behavior of NdFeO3. Ceramics International. June 27, 2025.